29 January 2019

By Tim Koch

Tim Koch goes east.

Most existing British rowing clubs of any age were originally ‘amateur’ as strictly defined by the Metropolitan (later ‘Amateur’) Rowing Association between 1879 and 1937. In that period, it was not only ‘professionals’ (i.e. those who rowed for money prizes) who were barred from competing alongside or against ‘gentlemen amateurs’, but so were ‘mechanics, artisans and labourers’ and anyone ‘engaged in any menial duty’.

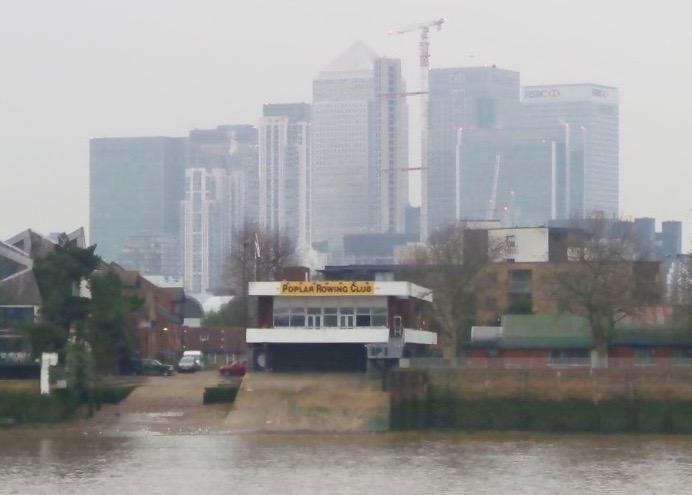

It is easy to understand why so few of the clubs that were originally for those engaged in manual work (‘tradesmen’) survive today. Most had a precarious existence, the majority were unlikely to be able to afford their own premises or even their own boats. When the boathouses that they hired craft from closed, or when the docks, wharves and warehouses that they rowed out of went out of business, the clubs disappeared. Of those few surviving former tradesmen’s clubs, perhaps the most notable is Poplar, Blackwall and District Rowing Club (PBDRC), based on the Isle of Dogs in East London, with its origins going as far back as 1854.

The closure of the docks was followed by the so-called ‘yuppie invasion’ of the 1980s. Notably, the former Canary Wharf became a financial centre. One of the results of this was that PBDRC now has a more socially mixed membership. This led the club captain, Chris Spencer, to joke in his speech at an Annual Club Dinner:‘For years we used to have East End people eating posh food, now we have posh people eating East End food.’

I had long wanted to visit PBDRC, partly because of its importance in rowing history and partly because I have often enjoyed the company of its members while attending the Doggett’s Coat and Badge Race. The dock workers are no more, but if a waterman or lighterman is going to join a rowing club, then Poplar, Blackwall and District is a very likely choice.

I recently had my excuse to travel across London and spend an evening in a packed PBDRC clubhouse. I had been invited to attend a screening of a new documentary, The World’s Oldest Boat Race. This film is part of the Thames Festival Trust’s heritage project exploring the history of the Doggett’s Coat and Badge. I will post exciting news about both the film and other work by the Trust very soon. Here, I am just going to chronicle my visit to the rowers of London E14.

While the club has few very old artefacts on display, its real treasures are its members and supporters, both past and present.

Dolly Woodward Fisher was educated at the prestigious Cheltenham Ladies College but, to her family’s distress, she married a lowly lighterman, William, winner of the 1911 Doggett’s. She ended up running a large lighterage business, transporting goods up and down the Thames. A woman who succeeded in a very tough, very male world, she dressed in man’s suit accessorised with a bow tie, monocle, and high-heeled crocodile shoes. The current Poplar boathouse was largely paid for by the money raised by her tireless efforts. A wonderful film about Dolly is on Vimeo. There is a section on the club from 23 minutes and 18 seconds in.

Frankie told me that the eight had only got together six weeks before Henley – unlike their well-trained opponents. He remembers that their training included performing a thousand consecutive rowing squats. The two coaches were legends of the rowing world: Ted Phelps and the 87-year-old Jack Beresford Senior.

In their first heat in the 1956 Thames Cup, Poplar beat University College, Dublin, by 2 3/4 lengths in a time of 7 min 20 secs. They recorded the fastest time of the day for the Thames Cup and The Times called them ‘impressive’. In heat two, they beat Queen’s University, Belfast, by 3/4 length in a time of 7 min 28 secs. On day three, Poplar beat Bristol University by four feet in 7 mins 19 secs. In the semi-final, they lost by one length to the Jumbo Edwards’ RAF crew who, in turn were beaten by the same amount in the final by Princeton University, USA. The Times said that Poplar ‘did splendidly to get so far at their first attempt’. Remarkably, there is brief newsreel film of the crew and Beresford Senior at Henley on the British Pathe site. The report on the 1956 regatta (‘One of the gayest sporting events of the English summer’ according to the commentator) starts at 1 min 4 secs. George, Frankie and friends are at 1 min 18 secs.

Superb article. I loved this line: “For years we used to have East End people eating posh food, now we have posh people eating East End food.” Rowing for all!

Very good that, but one section has got me wondering – the reference to a ‘Lifeboat’ pub. I’ve written more than a few blog articles about the Isle of Dogs (including one about Dolly Fisher: https://islandhistory.wordpress.com/2017/02/19/dolly-fisher-tugboat-annie-of-the-thames/), but have never heard of this pub. Can you say where you got the name from? My own association with the rowing club extends to not much more than parties and ‘do’s’. I did once in the 70s tried to sign up as a proper rowing member, but when I revealed I could hardly swim, I didn’t get beyond the training tank.

I joined the rowing club when it was a boathouse adjoined to the old station, waiting room where we got changed and had a cold shower. Tommy Yearsley was club captain about 1950, couldn’t swim a stroke was told if you come out the boat just hang on. How times have changed loved it

Dear Mick,

This information comes from Dolly Fisher herself, via a 1966 history on the PBDRC website:

Click to access Club-Memoirs-1854-1980.pdf

From records this club was formed roughly about 1854 by a group of young boys who wanted to row a boat. They could of course have been called “Would be oarsmen”. These young lads, and possibly their fathers, cadged from all and sundry and got one or two old boats together. They made their headquarters a pub known as the “Lifeboat” – later pulled down for the new tunnel (Blackwall). The boys evidently kept their boats in publicans backyards, and the boats were launched at Chalkstone Bouys, Millwall Stairs and the Dust Shute at Poplar Dock Causeway before it was closed, and sometimes at the upper end of South Dock.

Best wishes,

Tim.

Thanks for that, Tim, I’ll have a read of that. If the pub was that far north, having to make room for the tunnel, it’s not the Isle of Dogs, so totally foreign for me 🙂

Reblogged this on Cowboys and effigies.