29 November 2023

By Chris Dodd

The second part of Chris Dodd’s memories of the so-called 1987 Boat Race Mutiny. (Read Part I here.)

Buddies and a kangaroo court

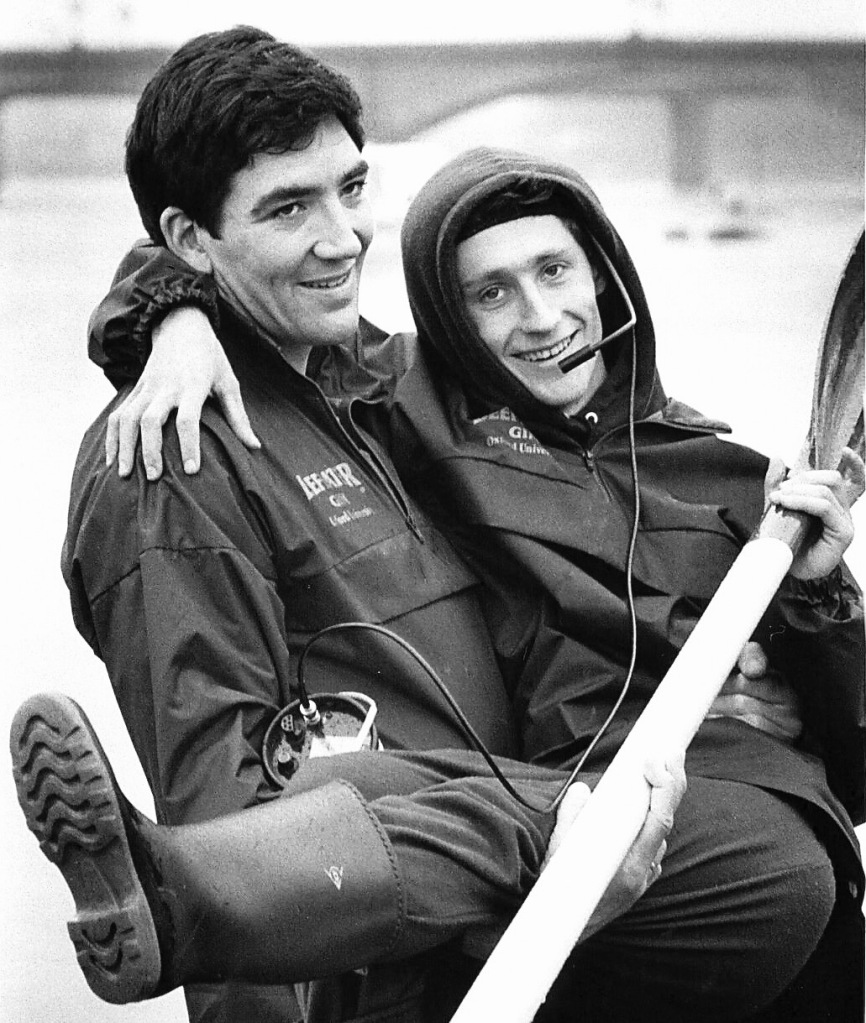

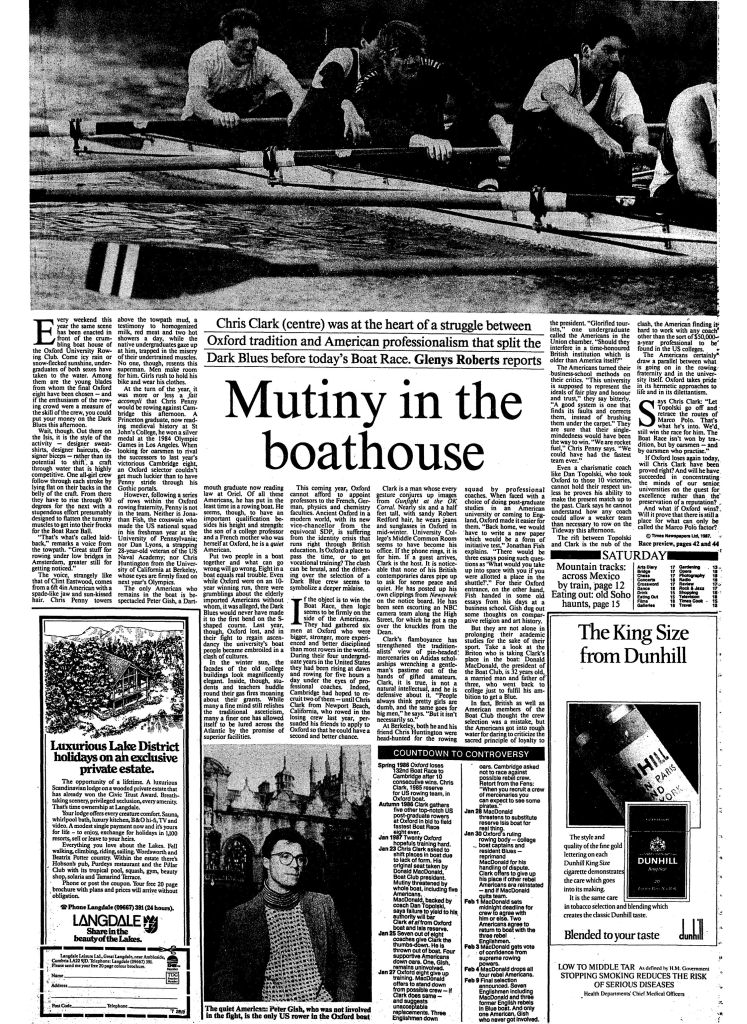

I remember door stopping an hours-long meeting of coaches called by chief coach Dan Topolski who required all eight of his attendant voluntary assistants (who included Matheson of the Independent and Page of the Telegraph) to agree that the meeting’s final statement would be unanimous. By now the popular press and much of the public interest in the mutiny attributed it to arrogant Americans who wished to row with their buddies at the expense of the innocent Brits. Meanwhile, the US cavalry and their British comrades talked of coach-crew meetings as kangaroo courts, with loyalty sown up in advance pledges to old heavies.

The Times and the Guardian correspondents waited patiently to ambush attendees for an impromptu press conference when the meeting broke up. What action would Dan and Donald make next? I can’t recall now what their next move was, but this meeting could have been the one that resulted in Clark being sacked, as mentioned above. Anyway, Mike Spracklen emerged and told us that his proposal to hear the case of the OUBC mutineers had been arbitrarily dismissed. And opinion was not unanimous, Spracklen added. He was not alone in advocating that their voice be heard.

A red letter day at the Pink Palace

A red letter day occurred on which the mutineers agreed to return to the boat of ’probables’ for its first outing since the crew had turned up at Marlow Scout Camp some weeks ago, having dumped their president at his home and commandeered the key of the minibus. Marlow was the first day of Spracklen’s coaching fortnight, and it was his last.

The ‘red letter’ occasion occurred on Matheson’s first day of coaching, and it turned out to be his last. It was also the last time the best crew who never rowed in the Boat Race sat in a boat together. On the afternoon in question I went to the gates of Oriel at 1pm, the customary time and place for Oxford crews to head off for training water at Marlow or Henley or Wallingford.

As I walked past a parked Volvo, its window opened and I was told to get in quick. The driver was coach and reporter Matheson. He explained that Donald and he were the only people who knew where the crew was headed and they were keeping it dark to prevent the public and press showing up. Oarsmen including mutineers somewhat sheepishly boarded their minibus. A BBC TV vehicle arrived as we drove out of Oriel Square in the Volvo. Hugh headed for Leander Club in Henley by a circuitous route to throw off anybody who attempted to tail us. We parked at Leander to see the minibus and boat trailer cross the bridge, followed by the BBC. Luckily, Leander’s pay phone was working and I was able to call the Guardian’s picture desk and direct Ken the photographer to come to Henley instead of Marlow.

The crew went afloat and disappeared down Henley Reach. When they returned towards dusk, Ken was on the bridge clicking his shutter. The boys were not happy as they came ashore and carried their boat to its trailer. Hugh’s attempt to talk them into continuing ran into sand. Gavin Stewart took me up the lane beside Leander and announced exclusively to the Guardian that he was resigning as vice-president because he thought Dan and Donald’s selection policy to be unfair. His eyes filled with tears.

Eventually Hugh and I walked over the bridge to the Red Lion Hotel where we ordered a proper English afternoon tea to sustain us while writing copy. We learned that Dan had contacted Kris Korzeniowski, chief coach in the US, to get the lowdown on Penny, Huntington, Lyons, Clark and cox Fish. Then we returned to Oxford to tour pizza places or curry houses and find Jim Railton to help him with his copy.

Conspirators at a loss

Having one day arranged to interview Jonathan Fish, the American cox, I had a shock when he showed me into his room to find half a dozen mutineers present, both Yanks and Brits. They asked for my advice because they were getting bad press. That was not surprising as their policy seemed to be to keep their lips tight, which allowed newsmen to speculate, indeed almost required us to do so in order to get a story. I said it would be unethical for me to offer advice even if I had any, because I was an observer, not a player. But, said I, decide what you want to tell the world before calling a press conference and set out your case clearly, point by point. If you level with the press, they’ll print it.

Don’t mention the mutiny

During their ten-year run of wins Oxford invited rowing correspondents to dinner at the house on Barnes Common where they spent the fortnight before the race. The evening was informal and centred round the landlady’s magnificent buffet in the company of the Blue Boat and their coaches. In 1987 rowing journalists speculated that invitations may not be forthcoming while Dan and Donald searched for oarsmen to meet Cambridge. But hey! A crew was put together by plundering the Isis reserves, and dinner with the press was on.

There was a certain frisson in the house. Rowers, coaches and correspondents spent time avoiding eye contact when they were not flashing glances when hearing a significant remark. The evening echoed Basil’s refrain ‘don’t mention the war’ as he goose-stepped out of the dining room at Fawlty Towers. ‘Don’t mention the Mutiny’ I told myself a hundred times.

And so to the stake boats…

On Boat Race Day the Dark Blues paddled away from their boathouse like kids unwillingly to school. After all, the day belonged to Cambridge. The Light Blues were an excellent crew untroubled by dispute and defending their historic win by seven lengths twelve months before. Everything was going their way, including the punters and rowing correspondents. Furthermore, they would start on the fancied Surrey station.

Oxford dragged themselves reluctantly to the stake boat. They were a motley lot of sometime active mutineers, mutiny sympathisers, oarsmen who didn’t want to hear about it, President Macdonald and guys kicked upstairs from the Isis reserve crew. Isis adopted the slogan ‘Isis is nicest’ but this past week they were frustrated at being disrupted for their race with Goldie.

The crews, I think, were late to attach to their stake boats, and a sudden electric storm frothed up the tide into a lumpy maelstrom. I was in a press launch sheltering under Putney Bridge when Valkyries danced on billowing clouds above and darkened the day to dusk, while speedily enshrouding the prospect of a Light Blue victory. For now the only shelter was under the lee of the wall along Bishops Park on the Middlesex station, leaving the Surrey side of the tide torrenting like rapids.

As the umpire caught a moment when neither cox had an arm raised to indicate that he was not straight, the crews went off, with Oxford’s Tom Cadoux-Hudson yelling at cox Lobbenberg to go for the wall, echoed by the screams of Topolski from his launch. After a few minutes Oxford were creaming away in flat water under the shelter of the wall while Cambridge could not help themselves by following their opponents for fear of fouling them.

The Light Blues burrowed into wind and waves, and when the boats came together near the Mile Post, Oxford had their nose in front. The underdogs found a spring in their hands driven by adrenaline that kept them ahead until they crossed the finish line with a further 3.25 miles from the Mile Post behind them.

Donald was once more a happy man. He hadn’t managed a smile since his presidential election day in the previous year. His crew, by no means as good as the best Oxford outfit not to win the race, had robbed Cambridge of victory by four lengths. He was a giant figure standing in the boat under Chiswick Bridge, arms aloft towards Valhalla.

A beginning to the end

That, of course, was not the end of the mutiny. It changed OUBC quite a bit. It spawned a book and a film, and Donald Macdonald admitted in his recent lecture at London RC that he, mutineers and the mutinous Blues are only now, after 30-odd years, ending their stand-off and willing to step aboard a boat and row it together.

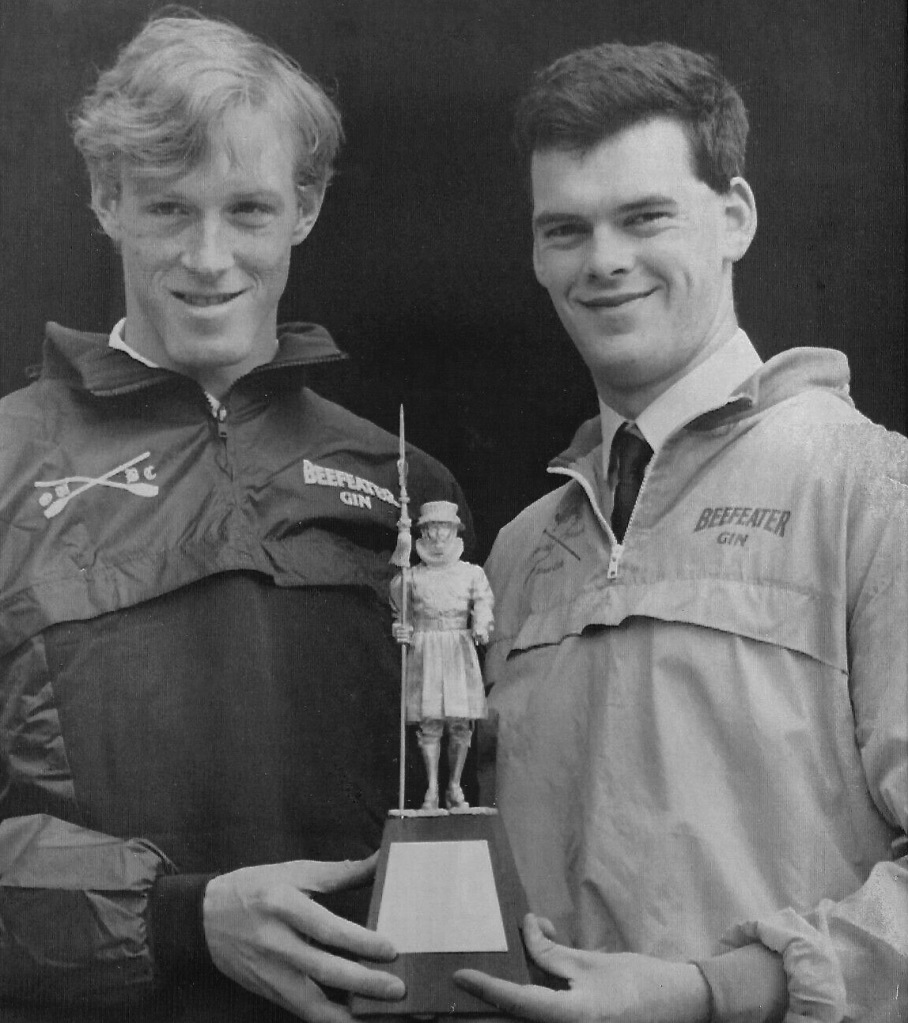

There were two candidates when OUBC met to elect a new president for the 1988 Boat Race. Macdonald was rooting for Tom Cadoux-Hudson, former London University oarsman, world championship medalist and medical student who had stayed out of the argument, while others supported the American Olympic champion, Chris Penny who was an active mutineer.

Before the election the two met and found that their ideas about OUBC were similar. They pledged that whoever lost would serve as the winner’s vice-president. Penny won by a majority of votes from boat club captains and a majority of Blues in residence. He appointed Britain’s best coach, Mike Spracklen, as Oxford’s finishing coach, and Penny’s crew won the race (Oxford won for four further years after 1988). Mutineer cox Jonathan Fish returned to the university to assist Spracklen, and Steve Royle became Oxford’s first professional manager-coach (Cambridge appointed a professional a year later). Topolski, whose companiero gave birth to an heir just before the race, never coached Oxford again, but he became an effective consultant for their adventures on the Tideway, especially on weather and its Wagnerian ways. And he became a happy family man.

The mutiny killed off Sidewinder and his fictional pairs of storekeepers (quite right too – Ed), but it produced a book, True Blue (1989), a page-turner ‘as told to’ tale by Patrick Robinson. Dan and Donald were the main sources, while Robinson, a former Daily Express journalist turned ghostwriter, spent most of his time in Florida. Consequently, he saw little of the action while peppering his book with small but irritating inaccuracies.

A few months later The Yanks at Oxford (1991) by Alison Gill attempted with some success to straighten things out. Robinson’s book led to a film of the same name by Ferdinand Fairfax, several of whose cast of unknowns are now knowns. The film contains some excellent rowing by Imperial College’s first eight masquerading as Cambridge; rowing slowly enough to allow the actors’ boat to beat them was a challenge.

Twenty years on…

In 2007, I contacted as many of 1987’s Oxford oarsmen as I could find and asked them for their thoughts twenty years after. Quite a few said that if the circumstances arose again they would take the same action. Several passive mutineers said that their sympathies were now or had been with the mutineers and their case. Several considered the reforms forced upon OUBC were an improvement in the way things were managed. A heap of responses can be seen in RowingVoice (volume 1 number 1, March 2007) and in the American magazine Independent Rowing News at about the same time. Meanwhile, here is just a taste of the responses:

Gavin Stewart in 2007: I started the mutiny as much as anyone else. For me, selection had ceased to be about finding the fastest boat and had become about finding Donald [Macdonald] a seat at the expense of either Tony [Ward] or Hugh [Pelham]. That seemed very wrong to me.

Steve Royle in 2007: We couldn’t turn their heads. Dan and I felt we’d failed, really, as management, one that they’d dug such a hole, and two that by not being hands on – we were all amateurs in those days, giving of our time for nothing – we weren’t there when these seeds were being sown. But I don’t think it damaged or hurt the club at all really. With an exercise like that you usually come out stronger. Because you must learn lessons, and this was a big lesson.

Tom Cadoux-Hudson in 2007: OUBC does learn. Oarsmen’s views must be taken into account, and usually are. You need to do the best with the people you’ve got.

Chris Huntington addressed the question of Buddies in 2007: The notion that ‘the Yanks wanted to keep their friends in the boat’ is total bullshit. It is a crazy idea. Talk to any bunch of athletes who are serious about a race which is on the line, and you will find that nobody is trying to get their buddies in the boat. When so much is on the line, it is truly a meritocracy. The fulcrum of the argument is that nobody wanted a buddy boat. That idea was patently wrong. What everyone wanted was the fastest boat on the water. After all, Daniel Topolski recruited us.

True to the Blues

When I was about to send these meanderings-in-mutiny to HTBS I happened upon the soundtrack of the True Blue movie when clearing out some old CDs. Renewed acquaintance with disc was timely, especially as I recalled purchasing it years ago in the ‘all items 2 zloty’ box outside a goldmine of a music shop in Krakow, Poland. I eagerly slotted the disc into my player. Damn me, but the mighty Bose announced True Blue to be a faulty piece of work, and refused to play it. I suppose that’s what you’d expect when roaming at sea among dreaming spires under an ominous Dark Blue fog enveloping the mysteries of a mutiny in Oxford.

Watch the race on YouTube.

Macdonald’s 90-second version of events is also on YouTube.

PS: I have no idea how Oxford’s poet or chancellor issues were resolved, but in the light of the Boat Club’s antics being Chancellor of Oxford University looks like a ticket to a quiet life.