29 March 2022

By Chris Dodd

In the fourth of HTBS’s occasional piece on the wisdom of George Pocock, Chris Dodd uncovers George’s affinity with flying boats and bespoke shells – and how to touch the divine on the lake.

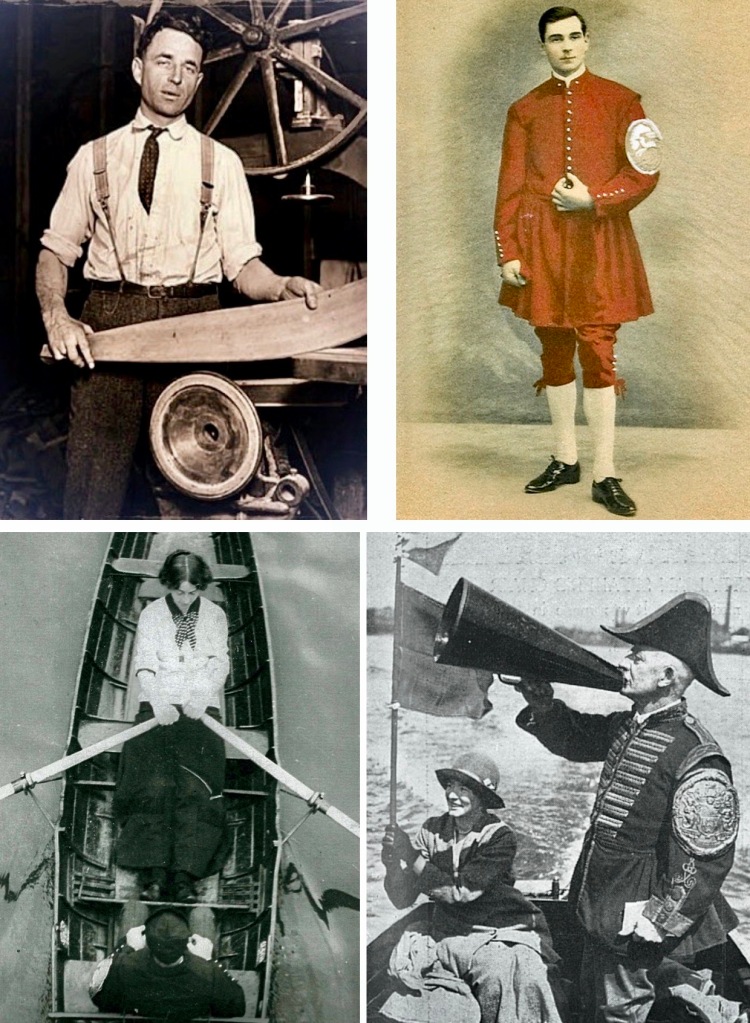

In 1912, the Pocock brothers received a visitor at their floating boathouse on the Coal Harbor in Vancouver. The figure pulling a dinghy erratically proved to be Hiram B ‘Conny’ Conibear, who enticed them to move to Seattle to build a fleet for the University of Washington’s burgeoning rowing programme. Rowing was not new to the university, but the Associated Students invited the maverick coach from Chicago to come and promote the crew programme.

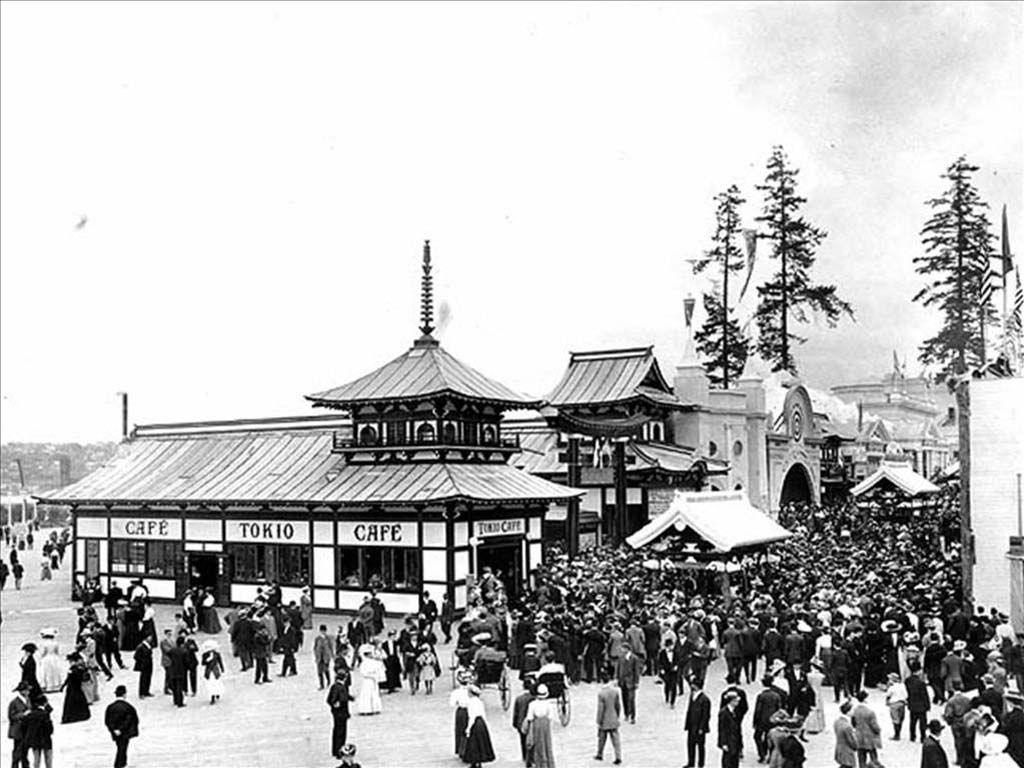

Dick and George took the Canadian Pacific day boat to Seattle to case the joint. What they found was a collection of poor buildings requisitioned after the Seattle exposition of 1909. The shell house on Lake Union was an abandoned Coast Guard station, and the proposed workshop was the Japanese pavilion known as Tokio Cafe (sic) or the Tokyo Tea Room. But lakes Washington and Union were eminently rowable and were soon to be joined by a canal. And Conny promised orders for twelve eights.

Conny’s order was reduced to one eight-oar, but the Pococks’ order book began to fill in both Vancouver and Seattle as word of their skills spread in colleges and clubs. They made boats in both places for a while, and their father Aaron and sisters Lucy and Kath arrived from England to bolster the labour force.

Then came a turn of events when world war broke out in Europe. Dr Suzzalo, the president of the university, brought a friend to the Tokyo Tearoom to inspect the workmanship. Mr W E Boeing was looking for someone to build pontoons for his new seaplane. Boeing asked George to make two pairs – essentially large Eton sculling boats enclosed by decks. When the U.S. entered the war in 1917, Boeing ordered 50 twin-float C-type planes. George, now working for the aeroplane company, hired 12 men and built all 150 pontoons at the rate of two a day. They were completed before a single airframe was ready.

George was in charge of 60 men when he left Boeing to return to boat building, and one of the skills he took with him was how to sort wood from trees:

‘One thing I was convinced of,’ he wrote in his memoir, ‘that we had far better material to plank those flying boats than the white pine they were all using. That material was vertical grain western red cedar. It is the wood eternal. It never rots. It does not swell or shrink in opposite moisture conditions, wet or dry. Western red cedar. Thuja Plicate is lighter, too. It would make a far better hull.’

The Navy Department agreed to use it for planking Boeing H S 2 hulls.

Dick and George carried on working for Boeing until 1922, the year in which George married Frances Huckle. George was forced to leave when the Seattle Post-Intelligencer published a story headed ‘Pocock to build shells again on the university campus’.

‘I didn’t know how the management at Boeing would take its publication,’ George wrote. ‘A man cannot split his loyalties – in this case the University of Washington’s and Boeing’s. It was, in the words of the poet, “Forsaking the substance for the shadow”.’

At around this time, Ed Leader, the new coach at UW, took the Varsity to second place at Poughkeepsie and received an offer he couldn’t refuse from Yale. Dick Pocock went east with Leader and built Yale boats for the rest of his working life.

In the months that followed George’s return to boat building, he felt that exchanging Boeing for a garret workshop on the campus was the mistake of his life. But when ‘Rusty’ Russell Stanley Callow took over as coach at UW, a new workshop was built above the hangar that served as a shell house.

George built a new eight and dropped it into Madison, Wisconsin, on its way to Poughkeepsie, where Conny’s daughter Catherine christened it Husky in Washington Lake water. George observed Rusty at work during the crew’s ten days of training on the filthy Hudson, filthy with sewage. ‘Rust’s handling of men was not to kill their spirit, but to raise it. He was a coach who never swore at his men but would crack a joke from the launch and make them all laugh; a real leader if ever there was one.’

George’s trips east on both aeroplane and rowing business registered the prejudice shown by the eastern press that he had to overcome in the 1920s. Newspapers looked askance at any article manufactured west of Chicago. He describes misfortunes befalling other makers’ boats being attributed to his marque, and notes with a flourish that his boats made rare appearances in the east during the 1920s, but twenty years on, there came a time when all thirty shells at Poughkeepsie were Pococks.

He quotes Longfellow’s “Psalm of Life” in support:

Let us then be up and doing

With a heart for any fate,

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labour, learn to wait

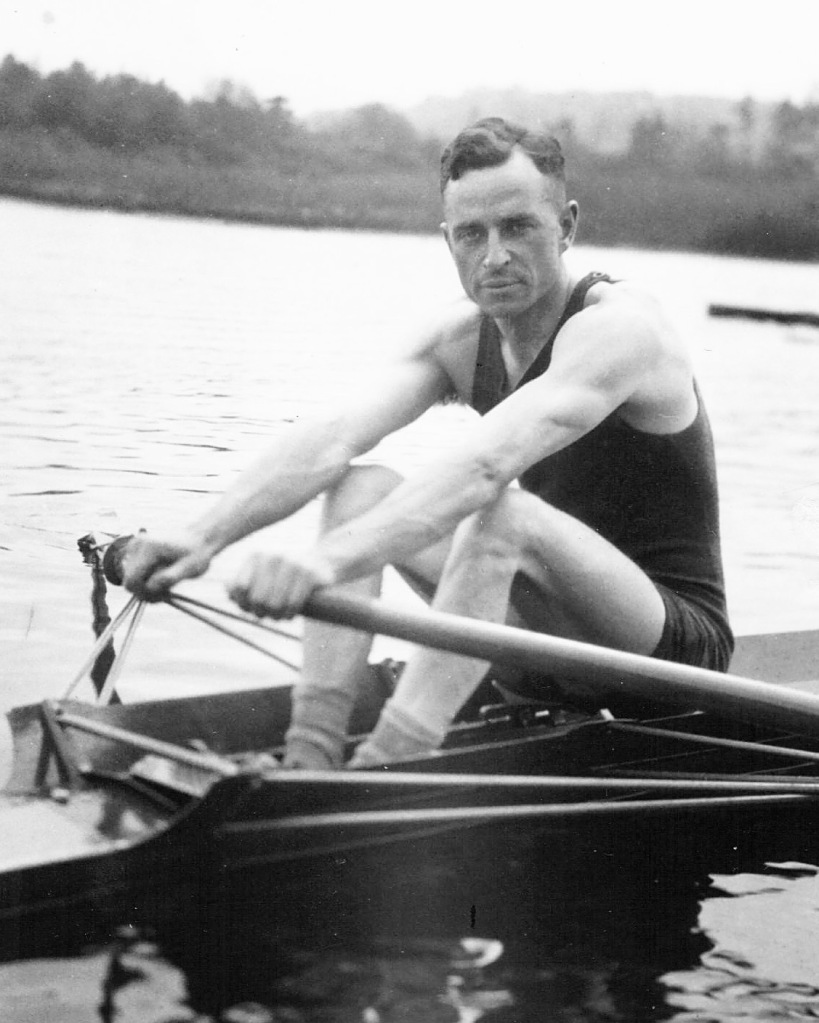

The University of Washington, whether by accident or design, grew into an unofficial coaching academy. A constant stream of visitors hung out in the shell house to hear George’s accounts of his grounding among Thames professionals, while he observed weird styles and tosh on the water when out sculling.

George lists the coaches that he watched and sometimes influenced. The Washington freshman coach Tom Bolles went to Harvard in 1936 and won all of his 36 races against Yale. The 1936 cox Bob Moch went on to Massachusetts Institute of technology. Gus Eriksen went on to Syracuse, Bud Raney to Columbia, Phil Leanderson followed Ulbrickson at Washington and Dick Erickson followed Leanderson. Meanwhile, Stan Pocock was the best head coach Washington never had because he ran the boat business alongside coaching, writes his Dad.

There was great talk about the ‘Washington stroke’ and a plethora of other strokes – e.g. the English Orthodox versus Fairbairnism when George was a boy. ‘I had quite a bit to do with the Washington stroke that became known as the Conibear,’ wrote George, but he also quoted Rusty Callow’s claim that ‘Conny never taught the same stroke two years running.’

In 1927, Rusty succumbed to an offer from the University of Pennsylvania and was replaced after Washington’s athletic chairman consulted George. Alvin ‘Al’ Ulbrickson was dubbed the ‘Dour Dane’ in the press. Both Al and George were modest, good listeners and learners.

George wrote a summary of his thoughts on how to row a shell.

I had 20 years rowing and sculling under old-time pros on the Thames in England. Rusty would get me to row by the crew in my single and tell them to watch the action of squeezing out the finish, coming up to the upright with the body, via leverage with the blades and not pulling via the feet, but having them loose; a smooth turn of the wrists, and the hands away smoothly and quickly, and when the arms were straight the slide moved slowly forward, not slowing the run of the boat; when at full reach, a slight hesitancy.

Now here is the spot in the stroke that can make or break the run. If you drive the legs too soon, you stop the run. If you try to catch the water without moving the slide, you either have to break the elbows down, or swing the back without moving the slide, which can cause a double stroke. So many crews develop a double stroke, a catch and a finish, which means coming over dead centre with no pull but drifting over.

The stroke described is one that eliminates this danger and can be executed in a one-piece drive. A good sculler of Thames fame will do them simultaneously; he will catch and drive with the legs at the same time, keeping his back in the same position and his arms straight. When this initial drive is midway, his blades will come over centre, his elbows bend down faster over dead centre, his back slowly comes over to about a 30-degree layback, his hands squeeze in for the force to keep the run on, and repeat as above.

These movements are almost impossible to put on paper or say by word of mouth; they have to be demonstrated. With constant practice the oarsman gets the feel of the boat. It has to be part of him. It is a live thing and it will work for him if it is handled right.

One of the curses of present-day rowing and equipment from abroad is the belief that change necessarily implies progress, George observed.

I am by birth, nature, and inclination a traditionalist in the art of rowing, sculling and shell building. I utterly dislike leaving the foothold that is proven over many, many years, mainly by professionals, who rowed for a living, until I have satisfied myself that the new style offers equally good standing. So far I have not been impressed with any of the new departures. I am reactionary.

In case you missed the point, the traditionalist elaborated his point:

It is hard to express what a top-notch crew must feel; probably “geared to the boat” might express it. There is no more pitiful sight than to see a crew abusing a shell, with the boat checking at every stroke, and the crew labouring hard, with little or no skill or artistry, just a catch and finish. Tempers must be held in check. No slashing at water to try and break their oars. Such are called ‘stoppers’. Thoughts have a lot to do with good rowing – coach, boats, mates. That is the formula for success – rowing with the head.

Rowing has great lessons of discipline in it. It is not a spectators’ sport, but a participant’s sport. I have said many times in public that a liberal interpretation of the word ‘rowing’ is overcoming difficulties. The opposite of rowing is ‘drifting’… I have never seen an oarsman drift through life. He is always willing to pull his weight. Rowing is conducive to good citizenship. By not promoting a rowing programme, high schools which are situated anywhere near water are missing the finest training a boy can get.

George also noted the importance of a good newspaper to creating a successful programme. In Seattle, 100,000 people would turn out to see a regatta.

For more information on flying boats and Boeing, see Way Enough! – Recollections of a Life in Rowing (2000) by Stanley William Pocock. For U.S. coaches, see Thomas C Mendenhall’s series of profiles in The Oarsman, c.1976-1980.