24 February 2022

By Chris Dodd

In the second occasional piece inspired by the wisdom of George Pocock’s memoirs, Chris Dodd explores lessons for life at the boatyard and on the Thames. (Part I here.)

George Pocock grew up by the Thames in a family of boisterous brothers, sisters and cousins with its roots in building boats – his father, uncles and both grandfathers were boat builders. George’s father Aaron’s business talents did not match his mastery of racing craft construction, but his multiple skills of the latter fed his wallet as he moved upstream and down as a journeyman, stopping at any yard with a full order book. The child George thus lived in Kingston, Shepperton, Windsor and Eton, and enjoyed riding on the cart with the removal men.

Aaron’s best break as the nineteenth century turned to the twentieth was to land a job as manager of the boathouses at Eton College, where rowing was a popular plank in the school’s nurture of character formation, and where there were hundreds of boats to maintain. Thus, George and his brother Dick were immersed in Thames and Eton lore. They were indentured to their father to learn the trade and sculled on the river cheek-by-jowl with the boys at Henry VII’s school while living under the shadow of Windsor Castle, home of monarchs. At one time, they occupied a cottage between the George Inn and the Waterman’s Arms, an experience that taught George not to drink.

The job that led Aaron to being appointed manager at Eton was to renew all the ‘lower eights’, the fleet of 56-feet lapstrake boats in Spanish cedar. Aaron’s kids had a dinghy to mess about in, and a family four to row (from the bow, George, Dick, Julia, Lucy, Kathleen the cox and Aaron squatting in the extreme stern), but when George was twelve, his father introduced George to the progression of college boats. The beginners’ boat was a wide stable craft called a ‘dodger’. The second was a ‘whiff gig’, less stable than a dodger and longer. Next came the ‘whiff’ that was narrow, long and very unstable. Last came a fixed seat racing shell, from which boys who won a race or excelled at scholarship progressed to a shell with a sliding seat. Thus, George and Dick rubbed shoulders with the men in the workshop and the Eton boys on the river. They became as proficient at sculling (as did their sister Lucy) as they were at building boats.

Aaron’s management style was easy-going, all his men being known by nicknames. Ben, Frank and Chippy the boat builders, Darky and Taffy the boat smiths, and four raftsmen – Ilo, Bosh, Froggy and Jack. Ben had been a professor in Cambridge, so it was said, but the circumstances that brought him to Eton are lost in the mist of the Cam. Frank was an ex-pro sculler from the famous Haines family of Old Windsor. He recounted exploits and passed on wisdom willingly. He taught George the importance of spring. When it came to oars and sculls, the custom at Eton was to get an oar that was so frightfully stiff you couldn’t budge it. According to Frank, they’re all wrong. ‘In my experience the best oar I’ve ever used in oars or sculls was one with a spring to it. A spring gives more purchase, more power, more feeling of mastery,’ Frank said.

George found out that he was right. ‘Any manual effort that needs a handle or a pole, stiffness is wrong. Springiness is what you want. Look what they are doing at the present day with the whippy fiberglass vaulting pole.’ A woodsman has a spring in the handle of his axe. A carpenter has spring in his hammer handle. A Chinese carrying a load could not do without spring in his pole, says the gospel according to George Pocock. I seem to remember similar arguments when carbon fibre oars and hulls appeared.

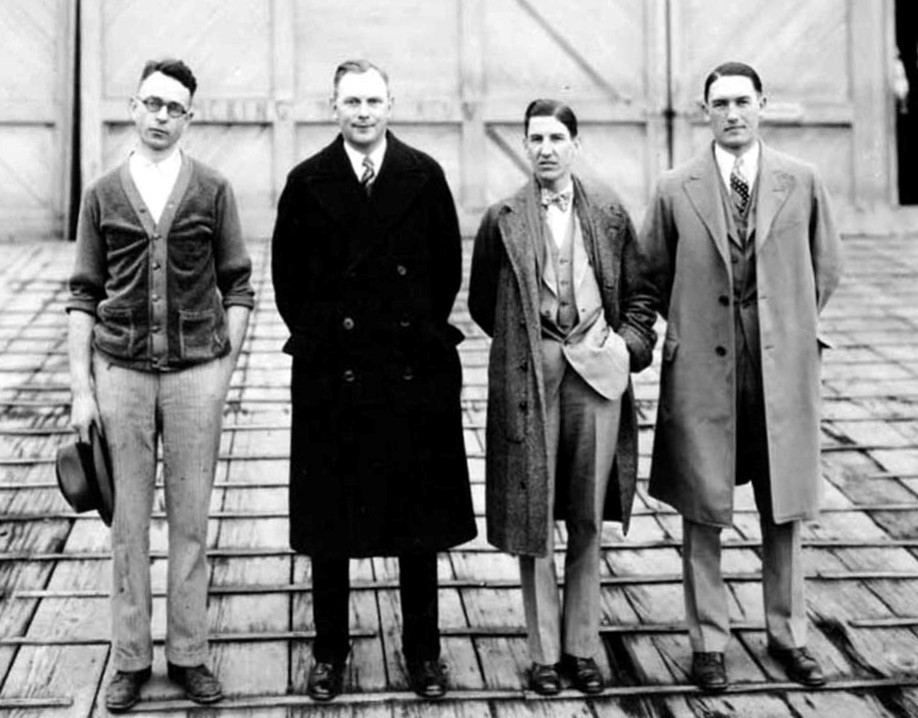

Growing up in Eton meant fishing, cycling, running and rifle shooting as well as the fragrance of sawdust and varnish and messing about on the river. Building and delivering boats, coaching and helping out on Rafts mingled George and his brother with the novices and coaches of the most prestigious rowing school. Among those he rubbed shoulders with were Prince Prajadhipok of Siam (future king), Lord Grosvenor (son of Duke of Westminster, richest toff in England), Holt and Cunard (heirs respectively to the shipping lines Blue Funnel and Cunard), Anthony Eden (future Prime Minister), J B S Haldane (prominent biochemist) and Tommy Sopwith (future aviation company). George recalls that Holt was overweight, so they built him a wide shallow single that became known as Holt’s war punt.

George was entered by his Dad for his first professional race when he was 17, a handicap from Hammersmith to Putney with Ernest Barry, champion of the world, as scratch. George built his own boat in white Norway pine with mahogany washboards for the race. He and Dick rowed their boats from Eton to Barnes and trained out of Green’s boathouse. George won two heats and qualified for the four-boat final against Charles ‘Wag’ Harding, the former champ of England, John Bowton, a burly policeman from Hackney, and Billy Coles of Erith. Aaron told George to keep an eye on Wag: ‘He knows the course blindfolded. He has lived on it. Be sure and keep him directly astern and you will not have to look around.’

After the lead changed several times, George and the cop arrived at Putney Bridge together. ‘I actually did not know whether I had won or not, and Bowton looked over at me and said, “You won”.’ The prize was £50, a fortune footed by the sponsors, the Nugget Shoe Polish Co and The Sportsman newspaper.

Aaron was keen that his sons should have a go at Doggett’s Coat and Badge, the race for watermen apprentices from London Bridge to Chelsea – a huge test of watermanship that you could only attempt once. Dick entered in 1910 and, two weeks before the race, the brothers sculled 35 miles to London Bridge where a mate of their Dad loaned them a shack to keep their boats. There were no changing or showering facilities, so they took the train from Eton every day and went out on tidal water that they were not familiar with.

Aaron was Bargemaster of the Fishmongers’ Company, making him starter and umpire of Doggett’s. This was a nerve-wracking task because a false start could not be called back on a running tide, and starting by megaphone was impossible because the competitors went off as soon as they saw the bullhorn raised to the starter’s lips. Raising an arm or firing a gun didn’t work either. Aaron’s solution was to hide behind the pilothouse of his launch until the pilot told him that the scullers were ready, prompting him to dash out and drop a flag. Dick’s preparation paid off, and he won the five-mile tidal tussle for an orange coat and silver badge, the badge of a top-rate sculler and wherryman. Another Pocock triumph occurred in 1912 when Lucy became the women’s sculling champion of England and was presented with a silver mirror by the Daily Mirror.

By the time George’s year for Doggett’s came round, the brothers were in America, so the younger one never had the opportunity to enter.

George’s diary reveals a passing interest in politics. During an election the candidates of the two main parties would hold meetings for those of their own political faith. ‘On one occasion when all the people had assembled in the hall, the chairman announced that the prospective Member of Parliament was leaving the platform to address his opponent’s meeting, and his opponent would be coming to address us. What a good idea!’

Thus was George shaped for life beside and on the Thames. He summarised his experience: ‘I have always felt that the unfolding and the arriving of a good athlete has an analogy to a successful life. An athlete cannot arrive at this peak in any easy manner. It is work, work, work until his choice of athletic endeavour is second nature. So it is with success in life’s endeavour. Most of our great men were poor boys. Want did not stop them. Want begets an energy that seldom yields to difficulties. What a bland existence life would be if there were no challenge to do better.’