Athens and London: Chance Encounters

30 August 2021

By Sandy Nairne and Peter Williams

HTBS is proud to be able to offer an excerpt, in three parts, from Sandy Nairne and Peter Williams’s forthcoming book Titan of the Thames: The Life of Lord Desborough. William Grenfell, later Lord Desborough, was a famous sportsman who competed in many sports, among them fencing, punting and rowing – he was a member of the famous 1877 Oxford ‘dead heat’ crew. For a presentation of the authors, please see the end of this installment.

When Mount Vesuvius erupted on 4 April 1906, few could have imagined the chain of events this would trigger, nor the consequences for William Grenfell, newly ennobled as Lord Desborough. It was the worst eruption since the 17th century and it soon became clear that Italy could no longer stage the next Olympic Games, planned for 1908 in Rome. The search would be on for an alternative location.

The 50-year-old all-round sportsman Lord Desborough sailed – literally and metaphorically – into this vacuum, and within months was offered the leadership challenge of his life: to stage an international event in London at a scale never previously seen, with no set budget, no government support, and with an almost impossibly tight timescale. The story of how this came about, and the success of the London Olympics that followed, delineates a pivotal point in his career, and was critical to the future of sport in Britain.

However, it was by chance that in the days following the eruption Desborough was making his first visit to Athens as a member of the British Olympic fencing team, participating in an ‘interim’ set of Games being held that spring, now known as the Intercalated Games. He met with other team members in Naples, including Lord Howard de Walden, in whose new steam yacht Branwen they were to sail to Athens. Desborough, however, was already worried: about the impact of the volcano, about his physical fitness and the suitability of the boat.

For an accomplished sportsman his nervousness was surprising: an element of his private self never visible in public. After leaving Marseille, he believed that ‘There may be trouble at Naples but I hope the worst is over – though the worst will not be over till the fencing is!’[1] On arrival in Naples he described the terrible scene:

Vesuvius is not to be seen. Two days ago it was very bad here – but nothing is falling at the moment. Everything, roofs etc. is deep in dust. I have seen our little yacht … She is very small, but I hope safe.[2]

The weather rather than the eruption made their next stage hazardous: by Wednesday the 18th they had only reached Messina, and Desborough wrote:

We have just put in here after a most awful day, a sort of hurricane & we have only done about 4 knots. Everything in ‘my cabin’ was drenched, so it is far from comfortable and no one turned up all day except Howard de Walden. I hope we shall not be storm bound here so as to make us late for everything. I do not see how anyone can fence after all this: & we now have to face the Adriatic in this little boat: she is only 68 tons nett.’[3]

Yet, despite storms, by the weekend Branwen docked safely in Athens and Desborough could focus his mind on his two roles: as a competitive fencer, with épée his speciality, and as sporting diplomat, one of two official British representatives at the Games (being Chairman of the British Olympic Association).[4] He wrote to his wife Ettie from the Hotel Imperial:

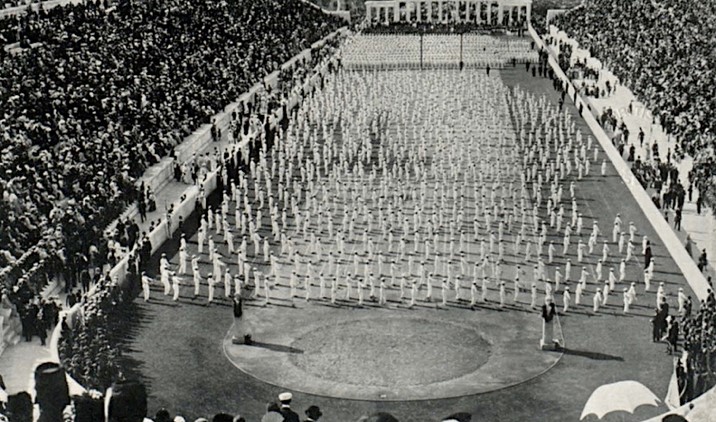

My dearest – We have at last arrived here very battered. I lunched with the Legation to meet the King and Prince of Wales, who were most kind. Then we processed with the other competitors round the stadium before 50,000 people, including the King and Queen, P & Princess of Wales, K of Greece etc. etc.. and now we are at the Hotel & just going to do a bit of fencing.

It was very silly coming here on a little yacht, nothing could have been worse. We fight the Germans on Tuesday: I do not know how good they are. … Athens is fascinating as far as I have seen it: we first went into Piraeus, & then to Phalerum where the yacht, absurd little boat, is now lying …The Greeks, I have come to the conclusion, know nothing whatever about the management of any form of athletic sports.

I am scratching this with the most awful row going on. Very best love, yr loving Willy[5]

* * * *

Vesuvius dramatically altered Italy’s national priorities. At short notice a new city was needed, and soon after his arrival in Athens Desborough was sounded out about whether London would be the host. He immediately saw this as an exceptional opportunity – both national and personal – and shrewdly recognised that royal approval might be critical.

King Edward VII was in Athens for the Games, as a guest of his brother-in-law King George I of Greece. Desborough had known Edward when Prince of Wales as a sporting enthusiast (they took part in the same shooting parties, and fencing was a shared interest). Athens provided a perfect opportunity for consultation with the King, if Desborough could fit it in around his fencing matches.[6] Still very nervous, he wrote to Ettie on 23 April:

I have been spending the morning at the palace where Seymour Fortescue sent for me to see the King – Our Queen was there, and says she is coming to see us fence the Germans tomorrow, & Princess Victoria and all the Greek Royalties, to say nothing of the King & Prince of Wales; it will be awful, we fight the German team at 11 o’clock, & I hope I shall beat them. The King has asked me to drive down with him to the fencing … but it will be awful if get whacked by these Germans. I will wire. It will be dreadfully hot fencing.[7]

He also confessed to Ettie that if Rome did fall through, he was already sketching out what London might entail:

I spoke to the King about it this morning and he highly approved. We could run at the Queen’s Club, Fence at Olympia, row on the Thames, Swim at Highgate Ponds – and I think make much more business like arrangements than they have here, but it would give me a lot to do as President of the Olympic Committee – we have no Stadium, which is seriously glorious, with the Acropolis above you in the sun, but could make a fine show at Olympia to wind up with; massed bands & crown the Victors …[8]

Desborough’s forceful imagination was now at work (though it’s hard to think how the modest scale of Highgate Ponds on Hampstead Heath could ever be deemed adequate) and soon he was committing himself very significantly. The next day he reported his contests to Ettie: relishing successful fights and the whole experience of the Games:

I began with the Captain of the German team & pursued him to the ropes & got in a rib-roaster which was a good beginning: & I had three fights and was not hit – so all was well … [after dinner last night] I spent the evening watching the illuminations between the two Queens – so you can see how regal I have been.[9]

However, a key issue that would be disruptive in London – fair adjudication – was forced on him very directly. On 26 he complained how, ‘We beat the Belgians this morning & did very well – then we fought the French and made a tie, & were finally beaten by 3 points: we really won but the judges treated us most unfairly, especially me which they all allow – I hit three straight off & was not allowed one. It was quite ridiculous, and I am frightfully annoyed.’[10]

Having now obtained a positive royal response, vital to his enterprise, Desborough wrote to Baron Pierre de Courbetin, President of the International Olympic Committee [IOC], before enjoying his final and festive day in Athens:

Yesterday I put on my gorgeous new uniform & had lunch with the King [of Greece] – a very big affair, and then we were given prizes in the Stadium – bunches of olive from the top of Olympia, & medals – very good ones – amid the cheers of the populace. We got these as second prize, & the Belgians got third. We really won without a doubt, and I am very sad about it … If the Games really come off in England in 1908 I shall have a very great deal to do being President of the Olympic Committee – but I do not know if we should be able to raise the money: one ought to have £10,000 guaranteed.[11]

As he travelled home from Athens, Desborough took the opportunity to discuss the complexities of staging a London Games with Theodore Cook and Cosmo Duff-Gordon, both of whom travelled back with him on the Branwen. Even before Desborough reached Paris (where he would fence competitively and hoped to gain outline agreement on the London option with de Courbetin), he wrote to Ettie from Venice:

I want to see Courbetin & Brunetta d’Usseaux about 1908; it will be a great business & one doesn’t quite see how to get the money – However if the King helped, as I believe he would, it would go all right.[12]

Typically of this determined and brilliant fixer he also arranged a stop in Rome to discuss with Italian officials their views on ‘the rules for several sports.’ [13]

* * * *

The birth of the modern Olympic Games in Athens in 1896 was the achievement of Baron Pierre de Courbetin, passionate about re-kindling the Olympic ideals of sportsmanship and international cooperation. These broad aims resonated with many others, particularly as colonial rivalries were overflowing at the end of the 19th century into the threat of more serious international conflicts. Desborough, in his summary report at the end of the 1908 Games, emphasized these ideals as the core purpose which went well beyond a regular athletic meeting:

… a dominant idea of the old Hellenic games was peace, and that although the superb physical efficiency they fostered naturally produced a citizen qualified in all respects to serve his state against a foreign enemy, the Olympic Games were the expression of good-fellowship as between Greek and Greek, the one institution, indeed, which united the Hellenic race during a history which was marred throughout by internal conflict … The same idea of peace and unity in connection with international athleticism is capable of a modern application.[14]

The British Olympic Association [BOA] had been founded in London in May 1905 at a meeting at the House of Commons presided over by Sir Howard Vincent, an MP and recently appointed as a British representative on the IOC. William Grenfell (becoming Lord Desborough at the end of 1905) was appointed as Chairman and, as well as signalling through this appointment a more serious interest in the Olympic idea, the Association gained an energetic and well-connected sporting figure who would give it considerable momentum.[15] A Council member at the time said Desborough possessed, ‘the skill of a D’Artagnan, the strength of a Porthos, the heart of an Athos, and the body of an Englishman.’[16] And a later commentator noted how, ‘With his rowing and swimming and fencing and tennis, his Lordship was, as Gilbert and Sullivan might have had it, the very model of a modern English Olympian.’[17]

Two other British figures made crucial and substantive commitments to the renewed Olympics. The Reverend R. S. de Courcy Laffan was a friend of de Courbetin since 1897, a former head of Cheltenham College who became vicar of St Stephen Walbrook and was appointed Secretary of the new BOA. Laffan emerged as the busiest figure at the centre of British Olympic organisation and was joined on the IOC by the equally determined Theodore Cook, an Oxford rowing blue, sportsman and writer (and later editor of The Field) who had assembled the fencing team for Athens.

After the fencing team’s return to Britain in 1906, as significant as royal approval was the engagement of the British sporting associations. Letters of consultation seeking support for a London Games were sent out, and positive responses came back. For many in ‘society’ and in senior sporting positions, horse-racing at Ascot, Henley Royal Regatta and the Wimbledon Tennis Championship were the important set-pieces of the summer season and adding a new clutch of international events was distracting and superfluous. Given the uncertainties around the Paris and St Louis Games in 1900 and 1904 respectively and the work that would be required for a London Games the endorsement of the sporting associations was a surprising but crucial outcome – a mark of trust in Lord Desborough (who went on to be President of the Lawn Tennis Association and the MCC).

Some may have hoped that Britain might make recompense for the sparse results in Athens. As Olympic historian Matthew Llewellyn puts it, ‘For a nation accustomed to claiming the laurels of victory and effortless superiority, Britain’s twenty-four medal (eight gold, eleven silver, and five bronze) Olympic campaign was viewed as a source of national embarrassment.’[18] However, if Britain claimed to have originated so many sports, now adopted elsewhere, decline might inevitably lie ahead. As Theodore Cook wrote, ‘England no longer stands alone, as she once did, as the apostle of “hard exercise” . . . We have had to see our best pupils beat us.’[19]

Desborough and the BOA moved quickly to create a British Olympic Council [BOC] specifically to organise the Games, and by the autumn of 1906 were in close deliberation about which events and venues would be needed and what monies required. Reflecting his determination to push on, several critical decisions were taken early. The BOC believed that each sporting association should take charge of organising their events within the Games, and that rules for each sport should be properly codified and agreed internationally, a hugely important step in terms of Olympic development. As Desborough put it:

Less than two years is a brief space in which to organise an international meeting for which … the ordinary period of four years has been found none too long … The work has been enormous, as … there are more than twenty separate competitions, and that for each of these separate books of rules have been drawn up, translated into French and German, and circulated in each of the competing countries. The organisation of the games themselves, the definition of the amateur qualification, the framing of the programme, the fixing of the number of competitors for each event, were all matters which have involved great thought and labour. The definition of the word ‘country’ also presented questions of no small difficulty.[20]

The newly-formed Olympic committees (in those countries wanting to participate in London) took responsibility for liaising with their own sporting associations in the selection of the best athletes, and this essentially set the pattern for future Olympiads. A later summary estimated that a ‘total of the more important letters exceeds ten thousand … and 800 officials [were] needed [for the Games].’[21] There was also the critical matter of raising sufficient finance.

However, Herbert Asquith as Chancellor of the Exchequer had already clarified the British government’s unhelpful position when he announced in March 1906, ‘I see no reason for granting any subsidy from public funds.’[22] This applied to Athens, but didn’t bode well for government interest in the Olympic enterprise as a whole. It meant the forty-strong British contingent for Athens had had to cover the costs themselves, and this favoured wealthy individuals. Lord Desborough was selected for the British fencing team because in Theodore Cook’s view he was ‘at the top of his game’. Cook couldn’t have known that Desborough’s presence in Athens would actually prove critical to bringing the Olympics to London for 1908.[23]

Part II will be published tomorrow.

The Authors

Sandy Nairne is a writer and curator and was previously programme director at Tate and then director of the National Portrait Gallery. He is currently chair of the Fabric Advisory Committee at St Paul’s Cathedral, and of the Maggie’s Art Group supporting Maggie’s cancer care centres, and a trustee of the National Trust.

Peter Williams is writer and researcher and a Departmental Fellow in the Department of Land Economy at Cambridge and a nationally recognised expert in his field of housing and mortgage markets. He is a Non-Executive Director of Vida Home Loans and Chair of First Affordable, an affordable housing provider as well as being part of an LSE London research team exploring “mortgage prisoners”. He is a co-editor/author of the annual UK Housing Review, now in its 29th year.

In 2015, Williams began researching and writing articles about sport on the River Thames, and Nairne and Williams, both being ex-oarsmen (and still competing in the sport of racing punting), realised there was no published biography of the great figure of Lord Desborough. After six years of exploring every aspect of Desborough’s life and work they are in the final stages of writing their biography.

[1] Lord Desborough to Ettie Desborough, 14 April 1906, on board S.S.Ortona, Hertfordshire Archives and Library Studies [HALS], D/ERv C1159/365.

[2] Ibid., 15 April 1906, on board S.S.Ortona, HALS, D/ERv C1159/366; Steam Yacht Branwen was launched in 1905, 135 feet length overall, and the first vessel built at the John I. Thornycroft & Company’s Woolston yard.

[3] Ibid., 18 April 1906, on board S.Y.Branwen RYS, HALS, D/ERv C1159/368.

[4] The other representative was Robert Bosanquet, archaeologist and director of the British School at Athens; he offered Desborough and the team a tour of the Parthenon and some of the ancient sites during their stay.

[5] Op.cit., 22 April 1906, Hotel Imperial Athens, HALS, D/ERv C1159/369.

[6] See comment on royal connections to fencing: https://www.leonpaul.com/wordpress/fencings-royal-connection/ .

[7] Seymour Fortescue was a former naval officer and equerry in the King’s service. Willy to Ettie, 23 April 1906, Hotel Imperial, Athens, HALS, D/ERv C1159/376.

[8] Op.cit., 23 April 1906, Hotel Imperial, Athens, HALS, D/ERv C1159/376.

[9] Ibid., 24 April 1906, Hotel Imperial, Athens, HALS, D/ERv C1159/370.

[10] Ibid., 26 April 1906, Hotel Imperial, Athens, HALS, D/ERv C1159/374 .

[11] Ibid., 18 April 1906, Ithica, Branwen, HALS, D/ERv C1159/380

[12] Ibid., 10 May 1906, S.S.Branwen RYS moored in Venice, HALS, D/ERv C1159/377; Count Eugenio Brunetta d’Usseaux was an Italian representative to the IOC; de Courbetin had deliberately not travelled to Athens for the Intercalated Games.

[13] See Theodore A Cook, The Cruise of the Branwen; and Willy to Ettie, 26 April 1906, Hotel Imperial, Athens, HALS, D/ERv C1159/373.

[14] Lord Desborough, Official Report for the London Olympic Games, summer 1908.

[15] Lincoln Allison points out in The Politics of Sport that, ‘the members [of the IOC] he recruited shared a similar aristocratic lifestyle and worldview. He chose people of independent means who were free from governmental influences, who themselves were influential and so could promote Olympism effectively, and who could make decisions reflecting the enlightened consensus of civilised men.’ … Initially the members were required to be able to pay their own expenses for international meetings. Manchester University Press, 1986, p222.

[16] Keith Baker, The 1908 Olympics, The first London Games, Sportsbooks, Cheltenham, 2008, p90.

[17] Frank Deford, ‘The Little-Known History of How the Modern Olympics Got Their Start’, in Smithsonian Magazine, July 2012

[18] Matthew P Llewellyn, ‘Rule Britannia: Nationalism, Identity, and the Modern Olympic Games’, PhD dissertation for the University of Pennsylvania, 2010, p54. The Athens 1906 Intercalated Games were later downgraded and are no longer regarded as part of the official sequence of Olympiads.

[19] Theodore Cook writing in Baily’s Magazine of Sports and Pastimes; quoted in Matthew P Llewellyn, ibid, p56.

[20] Lord Desborough, Chairman’s report, BOC, summer 1908.

[21] Theodore A Cook, The Olympic Games of 1908 – A Reply to Certain Criticisms, London, 31 October 1908, p14.

[22] Matthew P Llewellyn, op.cit., p35. The fact that other major international sporting events were staged without government support made government believe that subsidy was not appropriate for the Olympics.

[23] Phillip Barker, ‘The story of the first Lord of the London Olympic Rings’, https://www.insidethegames.biz/articles/17153/lord-desborough-the-niagara-falls-swimmer-who-helped-save-the-london-1908-games- [accessed 20 02 2020].

To be a bit pedantic, “Howard de Walden” should be called Lord Howard de Walden. In 1908 it would have been Thomas, 8th Baron Howard de Walden.

Thank you, Chris. “Lord” has now been added to Howard de Walden. / Göran

Great, and then what about the ‘Desborough Cut’ – when, why and who paid for it?

About the Desborough Cut – see here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Desborough_Cut

Our book will cover the creation of the Desborough Cut (originally named the Desborough Channel), a significant part of a wider flood prevention scheme, and fascinating not least because it was part-funded through a 1930s government public employment scheme.