The City of Dreaming Spires and The City of Angels

1 December 2020

By Tim Koch

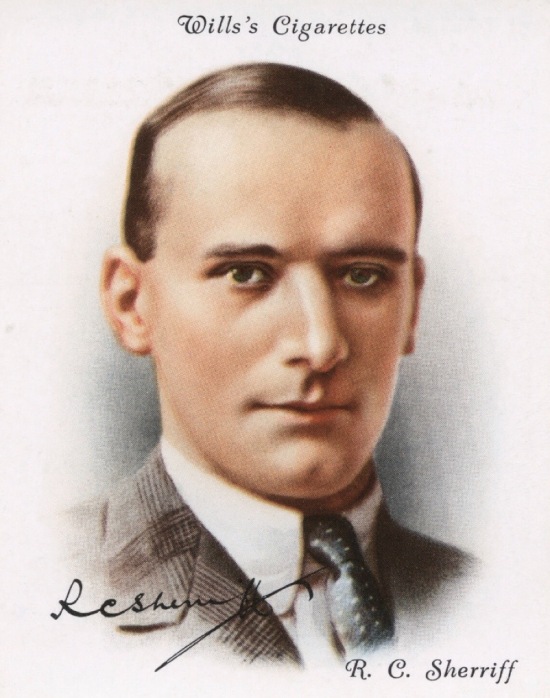

Tim Koch concludes the story of a remarkable writer and a dedicated oarsman. (Part I is here.)

When the 35-year-old R.C. Sherriff arrived at New College on 12 October 1931 he was, to the amusement of some, accompanied by his beloved mother, Connie, who was to live with him in Oxford. This was something that she had always done and would continue to do until her death in 1965. The only time that they were parted for any time was in 1916-17 and the suspicion is that, were mothers allowed in the trenches of the Western Front, Connie would have been there (this would have made Journey’s End a very different play).

It has often been noted that Connie was the only woman in Sherriff’s life, inferring that he was gay. However, Wales notes that, ‘there is no evidence of (him) entering into any kind of physical relationship with anyone. He would always remain most comfortable in the company of men…’

Students have many things that lead them to stray away from academic work and, for Sherriff, there was the common distraction of the New College Boat Club but also the less common distractions of the publication of a very successful new novel, The Fortnight in September, and the offer of writing screenplays and acting as a ‘script doctor’ in Hollywood. The latter came via James Whale, the director of the first stage production of Journey’s End who was now in California directing movies such as Waterloo Bridge and Frankenstein for Universal Pictures.

After two terms at Oxford, Sherriff had to explain to the warden of New College, HAL Fisher, that he would be missing his third term as, from March 1932, he would be temporarily working in Hollywood for $800 a week. However, Fisher may not have had too much of a problem with this as Roland Wales has found that Sherriff was a ‘Special Status Student’ who was not due to take any examinations and whose work may not even have been formally supervised. The ideal student life!

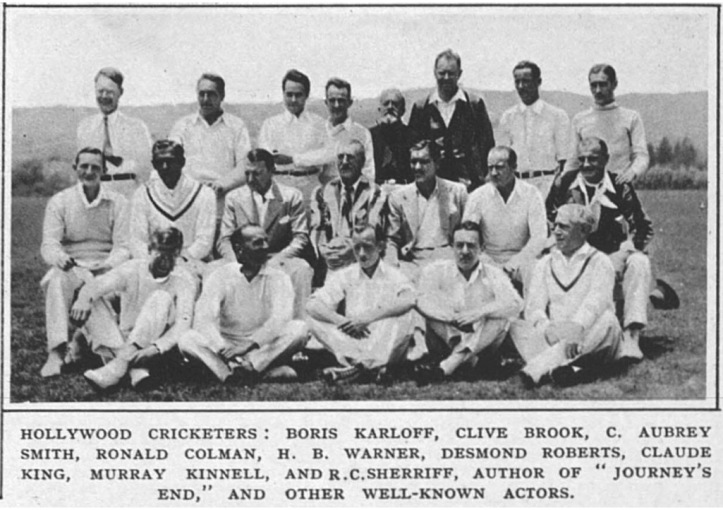

Sherriff settled easily into Californian life. He joined the Hollywood Cricket Club, the epicentre of the British film colony in Los Angeles. English grass seed had been imported for the pitch and the first secretary was PG Wodehouse. Thus on the cricket pitch, Sherriff may have found himself positioned at Long Stop while Sherlock Holmes (Basil Rathbone) was at Silly Mid Off, Sinbad the Sailor (Douglas Fairbanks Jr) at Fly Slip and Frankenstein’s Monster (Boris Karloff) at Deep Square Leg. Allegedly, Olivia De Havilland would be in the pavilion preparing the tea.

Sherriff liked Universal Pictures, America and Americans but Wales notes that ‘His decision to stay in Hollywood for only short periods (in the 1930s) helped him avoid being sucked into the Hollywood system and lifestyle’.

Wales quotes correspondence between Sherriff in Hollywood and the captain of New College Boat Club in Oxford:

I was feeling terribly homesick in America during Henley week: it was the first Henley I have missed since the war and I sincerely hope that I will not miss another one.

Before the start of the 1932 Summer Eights at Oxford, Sherriff cabled New College Boat Club in cod-American language:

Hope youse guys scram over de rival bozos in de stupendious boating blowoff dis weekend stop. Guess you’re swell outfit and am pulling for you to push all de other lugs into de seakale stop. Good luck to all de buddies. Sherriff.

In his book The Dam Busters (2003), John Ramsden noted the importance of the timing of Sherriff’s arrival in Hollywood in the early 1930s:

At exactly the moment when sound films were about to sweep all before them… Sherriff captured in “Journey’s End” the way in which a certain type of British officer and gentleman spoke and behaved. He then carried these manners and forms of expression into his screenplays, was much imitated in doing so, and saw them develop into clichés of cinematic Englishness.

Sherriff returned to Oxford for the start of the Michaelmas Term in October 1932. Wales says that, in his autobiography, Sherriff suggests that he was going to train for selection for the Oxford Boat to race against Cambridge but only illness prevented him. This seems unlikely: he was 36, had not rowed regularly for years, had a back injury and was not even in New College’s First Boat.

Although not rowing frustrated him, Sherriff took up coaching New College’s second and third boats. Strangely, in the 1933 Summer Eights, he coached New’s great rivals, Oriel, and with much success – they went from fourth place in Division I to ‘Head of the River’.

Why Sherriff coached a rival college is open to speculation. Possibly, Oriel offered him the First Boat and New did not, but more likely there was a dispute over rowing styles and equipment. For years before and after this time there was a ferocious ongoing debate between the adherents of the ‘Orthodox’ style and the supporters of the ‘Fairbairn’ or ‘Metropolitan’ style. The former tended to favour ‘fixed pin’ rowlocks, the latter ‘swivel’ rowlocks.

In its preview of the 1933 Summer Eights, The Times of 18 May backs up the idea that Sherriff went to Oriel because of a disagreement over styles and/or equipment.

The only crew (Magdalen) need to fear are Oriel, who have been well coached by Mr R.C. Sherriff. They are a typically ‘Metropolitan’ crew. Unlike Magdalen and Exeter, who have combined swivel rowlocks with a more or less orthodox style… Oriel are no respecters of tradition, but in their own way they row very well… They are supposed to be the fastest crew at Oxford…

Sherriff, coming from Kingston, would have rowed with swivels in the Faribairn/ Metropolitan style. As evidenced by the memoirs of Mike Ashby, New College only accepted swivel rowlocks in 1937.

By the summer of 1933, Sherriff had effectively left Oxford. However, he did some coaching at New College for the 1934 Summer Eights, even though he was no longer a student. New, second to Oriel at the top of Division I, chased their rivals over six nights but just failed to catch them.

The rest of the 1930s saw Sherriff travelling back and forth to California where he wrote, co-wrote and ‘doctored’ numerous film scripts. Coaching Kingston at the 1934 Henley Royal Regatta may have been Sherriff’s last active involvement with rowing for some time. I do not know how many more years, if any, he coached Kingston’s Henley crew(s) but the outbreak of war in September 1939 obviously stopped all such activities.

In 1939, unlike in 1914, Sherriff had no heroic ideas about war but did not want to appear to be ‘a shirker’. The 44-year-old applied to rejoin the East Surrey Regiment but was rejected. He also offered his writing and film skills to the Ministry of Information but had little response. In the end, he spent most of the war in Hollywood where he did comfortable but valuable work contributing to films that either rallied then neutral America to Britain’s side (such as The Lion Has Wings, This Above All and Mrs. Miniver) or which boosted morale at home with stories of Britain’s heroic past (such as Lady Hamilton). This subtle form of propaganda was by far the most effective kind, but Sherriff felt guilty about his easy war and returned permanently to Britain in mid-1944.

Living in wartime Britain took much getting used to and dealing with the austerity and uncertainty that followed the end of the war in 1945 was almost as difficult. However, by 1950 Sherriff had reestablished himself as a novelist, playwright and screenwriter. He felt that he could now treat himself to a new Rolls Royce and could again devote some time to coaching. In the early summer of 1950, he modestly offered his services to his old school, Kingston Grammar, and they were delighted to accept. Their joy increased when Sherriff turned out not only to be a good coach but also a generous benefactor, one who gave them a new eight named Home at Seven after his latest play.

Roland Wales:

When the new boat was… christened ‘Home at Seven’, he took the entire First VIII up to Scott’s (Restaurant) in the West End (of London) for dinner before taking them to Wyndham’s (Theatre), having held the curtain to accommodate their late arrival, so that they could see the play for which their boat had been named. This would be the first of many boats he would buy for the school, and the first of many occasions on which he would treat members of the KGS First VIII to a ‘slap-up feed’ and a show.

This was Roland Wales’ last reference to rowing in his Sherriff biography From Journey’s End to The Dam Busters: The Life of R.C. Sherriff, Playwright of the Trenches (2016). Sherriff’s Times obituary wrote that, ‘As Sherriff grew older, the place in his life of cricket and rowing was taken by archaeology’. At some time, he was made a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries.

The early 1950s were good years for Sherriff. His most notable success came with his Dam Busters screenplay. He had finished this in 1952, but production problems meant that the film was not released until 1955. Unusually, the script that he submitted survived virtually unchanged – a rare occurrence in film making. The critics single Sherriff out for praise and The Guardian said that he had ‘found the right dramatic dialogue for the men of 1939-45 as well as those of 1914-18’.

Sherriff managed to get two rowing references into The Dam Busters. The fact that Squadron Leader Henry Maudslay was Captain of Boats at Eton is mentioned and Squadron Leader Melvin ‘Dinghy’ Young’s 1938 Boat Race oar features in the sequence after the raid when the camera zooms in on various reminders of the aircrew who have failed to return

Sherriff was nominated for a BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) for his Dam Busters script, one of the two nominations he got for this award in 1955. The other was for the lesser known, The Night My Number Came Up. Unfortunately, though seemingly at the height of his screenwriting powers, these would be the last of his scripts to make it to the screen.

By the late 1950s/early 1960s, Sherriff’s style of writing was heavily out of favour. The up-and-coming playwrights were radical, working-class ‘angry young men’ who wrote ‘kitchen sink’ dramas. His 1960 play A Shred of Evidence was popular in the provinces but was panned by many London critics for being old-fashioned. Sherriff stopped writing for the stage by 1961, his last serious novel was in 1962 and a last script for television in 1964 went unproduced. The death of his beloved mother in 1965 was a further devastating blow. He published his slightly unreliable autobiography in 1968, a work that the veteran critic JC Trewin called ‘rare’ as it had ‘no stain of envy, no flick of malice’. His last book, a historical story for children, came out in 1973. Reclusive in his final years, Sherriff died on 13 November 1975.

An obituary by JC Trewin called Sherriff ‘the quiet man of the theatre’ and added ‘Where others pushed and thrust, he remained calm and self-effacing. Some may say too self-effacing…. he was always a gentle man…’ Perhaps this was the reason that the establishment overlooked him for a Knighthood or even a lowly OBE.

In his lifetime, Sherriff endowed a scholarship at Oxford and gave Kingston Grammar School land on which to build a boat house. He donated boats to KGS and to Kingston Rowing Club. In his will, he gave half of his royalties to KGS and the other half to the Scout Association. He also bequeathed his home to Elmbridge Borough Council as an arts venue (this was later sold, and the profits established the RC Sherriff Trust to support the arts in the borough).

Despite this generosity, most would agree that R.C. Sherriff’s real and lasting legacy was Journey’s End.

Those in the UK can watch the 2017 feature film of Journey’s End until 14 December on BBC iPlayer and a 1988 television production with Timothy Spall is on YouTube. Also on YouTube is an eight-minute video on Sherriff’s military career.