Vimy Ridge and Kingston upon Thames

30 November 2020

By Tim Koch

Tim Koch on the oarsman behind a defining play and an iconic film.

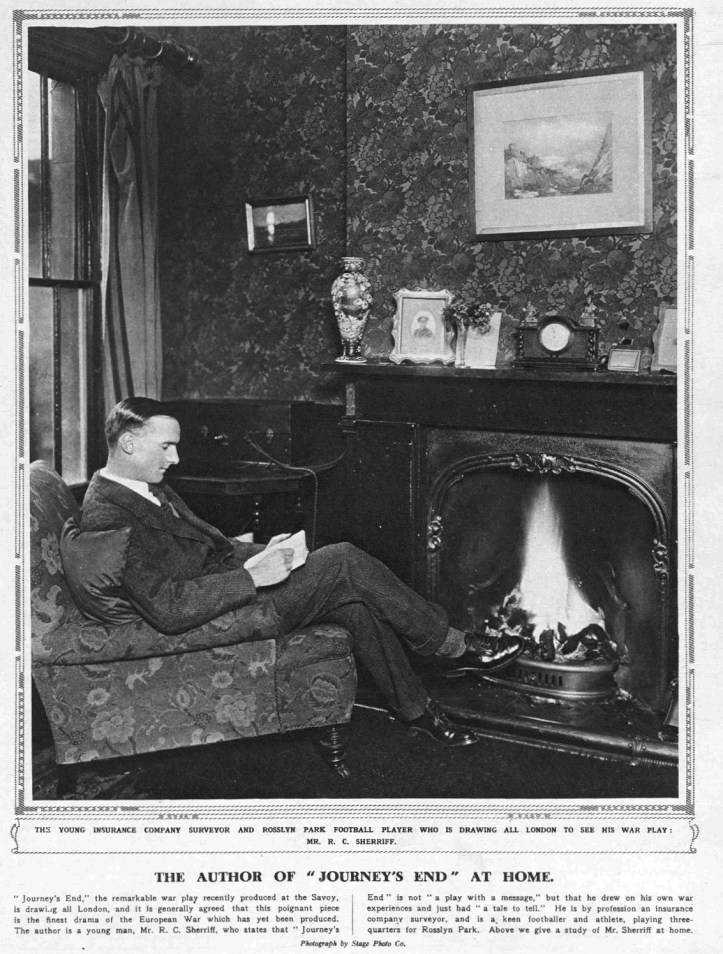

HTBS readers are a fairly knowledgeable breed but many will, like I did, react a little blankly when trying to think why the name ‘R.C. Sherriff’ is vaguely familiar. Learning his rarely used full name of Robert Cedric ‘Bob’ Sherriff is of no help in placing him but a mention of his greatest work certainly is: Journey’s End.

The most enduring literary legacies of the First World War are, arguably, the works of the so-called ‘War Poets’ (Owen, Sassoon, Brooke, Graves et al), Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, Brittain’s Testament of Youth, Graves’ Goodbye to All That – and Sherriff’s 1928 play Journey’s End. Set in an officers’ dugout over a period of four days in 1918, Journey’s End, perhaps more than any other work of fiction, has shaped our vision of the First World War. Its dramatic, tense and claustrophobic events have a genuine realism, not least because Sherriff had seen war at first-hand. Sheriff used each character to show the various things that men did to cope with the horrors of war, they are divided between those who could disguise their fear and those who could not. Today, there is a danger that we see the characters as stereotypes but that is not how war veterans of the time saw them. The ultimate confirmation of the authenticity of Journey’s End came in 1929 at the conclusion of a special performance for holders of the Victoria Cross when Sherriff was applauded for many minutes.

Journey’s End is often called an ‘anti-war play’ but, if this is true, Sherriff did not intend it to be. Perhaps it was simply a story of four days in the line. In January 1929, Sherriff wrote ‘I have not written this play as a piece of propaganda. And certainly not as propaganda for peace’. He was a man of conservative views, when he was sent to Glasgow as part of a military force following riots by strikers and the unemployed on 31 January 1919, he favoured violent and even deadly suppression of the discontent.

Over the last 90 years, Journey’s End has often been revived by both professional and amateur companies and versions in many languages for the stage, film, radio and television continue to be produced. A new feature film was released as recently as 2017. In English schools, it is a set text in English Literature exams. Sherriff wrote many plays, books and screenplays in his lifetime and, though his works met with varying degrees of success, none eclipsed Journey’s End.

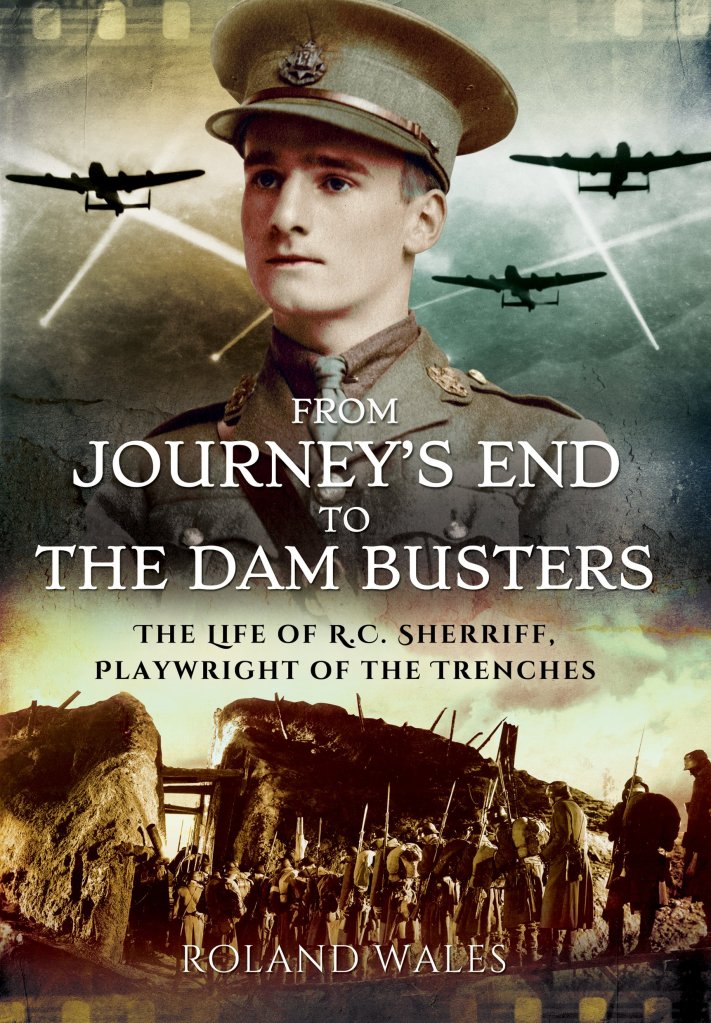

A more popularist recognition of Sherriff’s prodigious output comes with the knowledge that he wrote or contributed to many screenplays for British and American films, including The Invisible Man (1933), Goodbye, Mr Chips (1939), The Four Feathers (1939), Mrs Miniver (uncredited, 1942), The Night My Number Came Up (1955) and The Dam Busters (1955). His works for the latter two were BAFTA nominated and his contribution to Mr Chips was Oscar nominated with two other writers.

Thus, Sherriff’s career was bookended by a huge hit set in each World War: Journey’s End and The Dam Busters.

Wales’ biography on the website of his publishers Pen and Sword says:

Roland Wales worked as an economist at the Bank of England for many years, and then as Policy Director at the Labour Party. He became interested in R.C. Sherriff when his two sons attended Sherriff’s old school, Kingston Grammar, and he became Chair of the parents’ support group for rowing – the Sherriff Club. He produced several Sherriff-themed theatrical nights, and worked closely with the Surrey History Centre in their successful bid for Heritage Lottery Fund support of the Sherriff Archive, including writing a well reviewed play, ‘How Like It All Is’, examining the links between Sherriff’s wartime experiences and his subsequent work.

Sherriff published an autobiography in 1968 (No Leading Lady) and left a large archive. A lesser biographer would have relied almost exclusively on these, but Wales has proved that, in telling the R.C. Sherriff story, Sherriff himself is a very unreliable source. Wales’s remarkable interest in the man can be followed on his website.

R.C. Sherriff was born in 1896, the son of an insurance clerk. He attended Kingston Grammar School where he had an acceptable academic record but a distinguished sporting one. By his final school year, 1913, the natural athlete had become captain of rowing and cricket and won the Victor Ludorum at the school sports day with victories in the long jump, the high jump, the 100 yards and the quarter mile.

When the First World War broke out in August 1914, Sherriff’s employers initially pressured him not to enlist due to staff shortages. He eventually joined up in late 1915 and trained with the Artists Rifles, a regiment that attracted ‘Varsity types, rowing men and athletes of every description’. He was commissioned into the East Surrey Regiment in August 1916, arrived in France two months later and served at Vimy Ridge, Hooge and Ypres. Inevitably, the mental strain was enormous, alleviated only by the close bonds that he formed with his fellow officers. Sherriff’s war ended in August 1917 when he was wounded and sent back to England.

On returning to civilian life in February 1919, Sherriff unwillingly went back to the dull insurance job that he had left in 1915. However, in his free time he was writing both fiction and non-fiction and he was keen to return to rowing. In his autobiography, he claimed that he used his war wound gratuity to buy a sculling boat and, in May 1919, he became the secretary of the newly established rowing club for Kingston Grammar School old boys (‘Old Kingstonians’).

The Old Kingstonian rowing club did not last long but it may have aided Sherriff’s entry into Kingston Rowing Club (KRC), one of rowing’s ‘Grand Old Clubs’ founded in 1858 and then with 18 Henley wins in its history. He claimed that previously only public school boys were accepted by KRC and that he was one of the first grammar school boys to become a member, five votes for and four votes against. According to Roland Wales:

Within a year, (Sherriff) had made his way into the KRC crew competing in the Henley Royal Regatta. He would represent KRC at Henley several times in the 1920s, and the event would remain, for him, an annual highlight throughout his life.

In 1921, using members of Kingston Rowing Club and the Old Kingstonian Association, Sherriff was the prime mover in establishing The Adventurers, the theatre group that would perform his first five plays. Their opening performance was on 18 November 1921 when they put on A Hitch in the Proceedings, Sherriff’s first work for the stage.

Roland Wales:

Sherriff tells the story that the purpose of (this performance) was to raise money for Kingston Rowing Club, but the programme for the evening tells a different story: in fact, it was in aid of the Restoration Fund for Kingston Grammar School’s Lovekyn Chapel…

For Sherriff, the desire to fundraise, whoever for, may have been secondary to having his work put on in public.

Wales again:

‘Rowing and writing went well together’, wrote Sherriff, and for him they certainly did. Over the next four years he had four new plays performed by The Adventurers… and he became an important figure in both the Kingston Rowing Club and the Old Kingstonian Association.

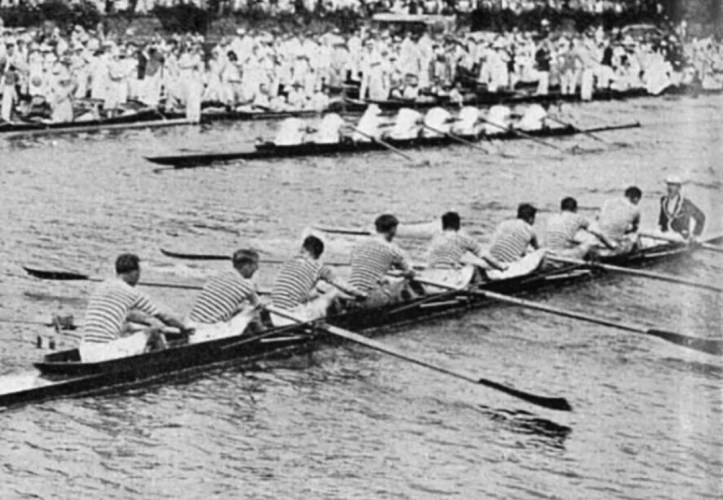

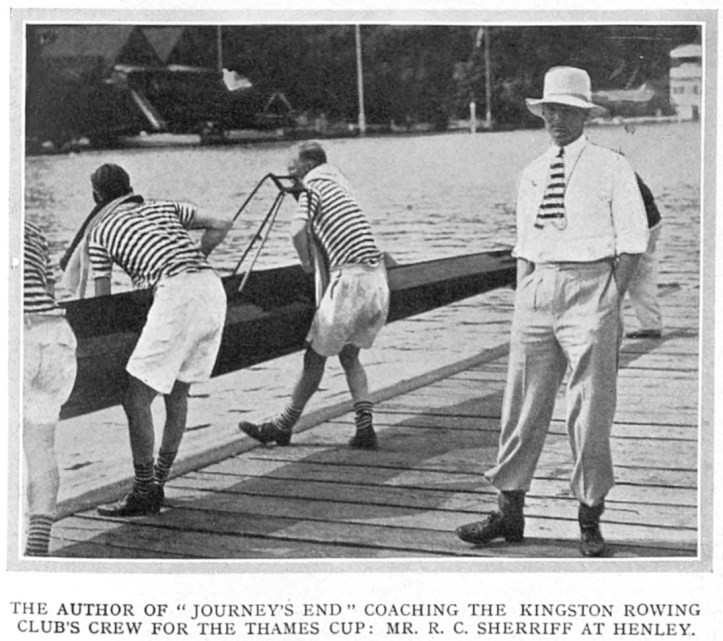

Despite still working in insurance and continually writing, Sherriff became Vice-Captain of Kingston RC in 1923, serving under the Captain, Gerry Oldham. Sherriff stroked the Junior Eight that won at Molesey in 1923 and was in the Kingston Thames Cup crew for Henley in 1924 (‘6’), 1925 (‘3’) and 1926 (‘2’). When Gerry Oldham handed the captaincy over to Sherriff in 1926, a letter of his in the club archives quoted by Wales says ‘I could not leave (the club) in better hands, nor could I have a better lieutenant’.

Wales notes that, by 1926:

(Sherriff’s) own rowing began to take a back seat; after all, he was now thirty years old, and there were lots of keen young members arriving at the club. So 1926 turned out to be his last appearance at Henley Royal Regatta but at least he went out in style.

With Sherriff at ‘2’, Kingston raced Jesus College, Cambridge, in the first round of the 1926 Thames Cup. The Times of 2 July wrote:

The favourites for the (Thames) Cup, Kingston Rowing Club, gave their supporters a fright in their heat with Jesus College, Cambridge. Although rowing a very fast stroke, Kingston could not shake the Cambridge crew off, and the crews had a very fine race along the enclosures, where Jesus gained steadily, but Kingston hung onto them, and won by a quarter of a length in the fast time of 7 minutes 11 seconds…

On 3 July, The Times reported:

Kingston beat the Midland Bank second crew by one length in 7 minutes 21 seconds after doing 3 minutes 28 seconds to Fawley. Kingston row in very good form and should win the event.

The Times of 4 July:

The standard (of the Thames Cup) this year was exceptionally high, and all four crews were within a second or two of ‘record’ in the semi-finals… Kingston led by half a length at the top of the island. They were clear before Remenham Barrier and passed Fawley 1 1/4 lengths ahead in 3 minutes 24 seconds, one second inside ‘record’… (Thames) were beaten by three-quarters of a length in 7 minutes 8 seconds, 2 seconds over ‘record’.

The final of the Thames Cup was on the same day, Saturday, as the semi-finals:

Kingston led at the start, and got half a length at once, but (Selwyn College, Cambridge) spurted level at Remenham. At Fawley… Kingston were just in front again, but at the mile Selwyn were a canvas in front, and longer than Kingston. Both crews were striking 35, but Selwyn just had the better pace, and won a thrilling race in 7 minutes 9 seconds.

Roland Wales:

Sherriff continued to row, popping up in races from time to time, but not at the Henley level any longer. He became a ‘popular captain of the club’, according to the ‘Surrey Comet’ and continued the position for three years – three years during which he would balance his captaincy duties with writing the play that would thrill audiences around the world, and change his life completely….

Sherriff began writing (Journey’s End) in the summer of 1927… He had not written anything (for 18 months) perhaps because his duties as newly minted captain of Kingston Rowing Club were rather more onerous than those of vice captain, but the itch to write had not gone away, and after the Henley Regatta had drawn the rowing season to a close in July 1927, he picked up his pencil once more.

In one of his quotable but unreliable stories, in 1968 Sherriff told the Belfast Telegraph, ‘Originally (“Journey’s End”) was written for my friends in Kingston Rowing Club, but they turned it down because they could not produce the necessary bangs and crumps’.

To make a very long story very short, after many difficulties Journey’s End was premiered on 9 December 1928 and was an instant success, the critics and the public almost unanimous in their praise. Even before the first night had finished, Sherriff was approached during the interval by the great publisher Victor Gollancz, who told him that he wanted to publish the play. In London, it ran for 594 performances and on Broadway for 485.

The fears that Journey’s End would fail because there were no women, because it was based entirely in a dugout and because the ending was downbeat were unfounded. However, the left-leaning New Statesman was critical of a play primarily featuring ‘the officer class’ and called it ‘an orgy of the public school spirit’ (seemingly ignoring the character of Trotter, the brave, dutiful and likable officer from the ‘lower classes’).

As an aside, Sherriff had a lot of luck in putting on his first production of Journey’s End, notably finding an unknown director, James Whale, and a little-known actor, Laurence Olivier. Whale, a veteran of Passchendale, later became an important Hollywood film director and Olivier became a dominant force on stage, screen and television for over 50 years. Also, six of that first cast had fought in the war and some wore their own old uniforms on stage. Sherriff lent Olivier his Captain’s tunic – only a Military Cross ribbon had to be added.

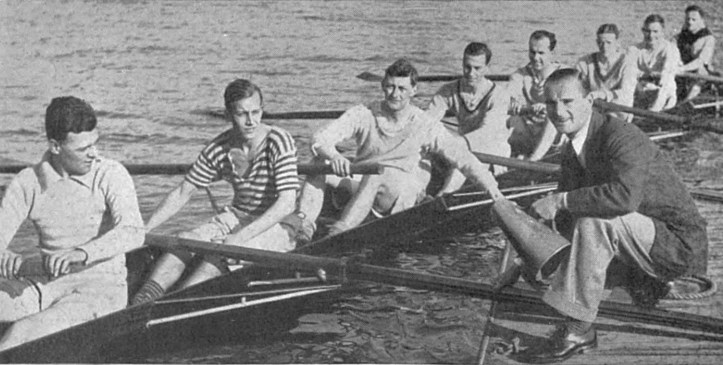

Although Journey’s End changed Sherriff’s world overnight (not least financially), he still had time for rowing and his beloved Kingston RC. The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News of 22 June 1929 wrote:

…although (Sherriff) is hard at work on a new play, he has decided to take a fortnight off to tutor the Kingston eight (for Henley). Sherriff is fonder of rowing than anything else that can be named – except, perhaps, writing money spinners like “Journey’s End” – and he has the reputation of being an admirable coach. It is believed that one of these days he will turn out a play with a rowing interest.

Sadly (but not surprisingly), the ‘rowing interest’ play never materialised.

The success of Journey’s End gave Sherriff a vast workload dealing with tedious legal and financial issues concerning multiple productions at home and abroad. Also, he was writing a novelised version and arguing with American film producers over a proposed ‘talkie’. Surprisingly then, he was still captain of Kingston Rowing Club and stood and was elected for another term on 23 October 1929. In May 1930, he bought Kingston a new eight, a generous gift certainly, but no hardship. Roland Wales has worked out that, by the end of 1929, Sherriff’s play had earned him 129 times his previous annual salary.

After Journey’s End, Sherriff suffered from the difficult ‘second album’ syndrome and had modest or no success with his writings (though, after debuting with a play about impending death in war, in making his next production a village comedy called Badger’s Green, he was setting himself up for failure). He then decided on a rather strange course and applied to New College, Oxford, to read history. New agreed to admit him as a mature student from October 1931. Possibly this was an elaborate way of overcoming his ‘writers block’, possibly the insecure Sherriff felt that he had something to prove. Whatever the reason, the chance to row at – and just maybe for – Oxford would surely have played some part in his decision.

Part II will be posted tomorrow.

Those in the UK can watch the 2017 feature film of Journey’s End until 14 December on BBC iPlayer and a 1988 television production with Timothy Spall is on YouTube. Also on YouTube is an eight-minute video on Sherriff’s military career.

Dear HTBS Fascinating post about a great author and a great club. Looking forward to part two. A footnote which highlights how different was the English rowing scene from today’s: the Jesus Coll Cambridge crew which gave Sheriff’s crew a scare in the first round of the 1926 Thames Cup was of course the college’s second VIII – in a year when the first won the Ladies. What college second eight today could give a major club’s first eight a fight down the enclosures?! Thanks for another wonderfully diverting HTBS lockdown-alleviating story! Peter Ackroyd

Nice work, Tim. As usual.