13 September 2017

Greg Denieffe writes:

Today, I am doing something I have done on this day for many years. The only difference is that today I’m doing it a little more publically and that is all thanks to HTBS’s policy of allowing the elves an occasional ‘nothing to do with rowing’ post.

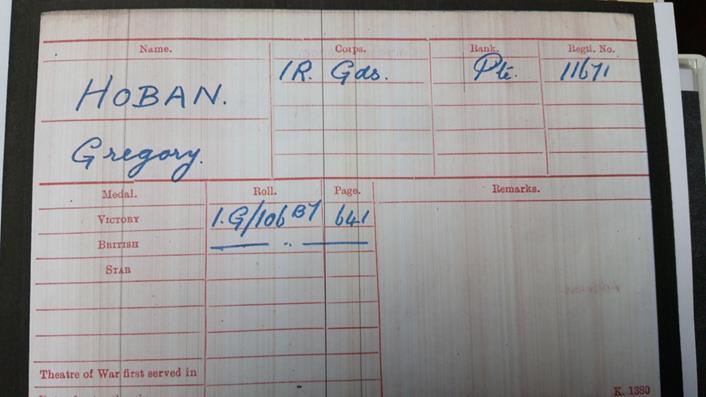

My great-uncle, Greg Hoban, after whom I am named, was killed in action exactly 100 years ago today. Greg was my paternal grandmother’s brother and joined the Irish Guards on 22 November 1916; he was probably 17 years of age (aged 12 on the 1911 census) at the time and joined up as a volunteer. If I remember correctly, the tale told me years ago by my late father, Greg’s brother-in-law Nicholas Dreeling, himself a Private in the 2nd Batt. Irish Guards, was home on leave and Greg ‘went back with him’. Sadly, Nicholas was killed in action on 9 October 1917, less than a month after Greg; he was 33, Greg was only a boy of 18 when he was killed; both were from the small County Kilkenny village of Gowran. In truth, it is more complicated, for not only did Greg volunteer, but so did my paternal great-uncle, Patrick Denieffe. He enlisted into the Irish Guards (regimental no. 11668) two days before Greg (regimental no. 11671) and it was his encouragement to enlist that persuaded Greg to go with him to the Western Front. My grandmother, Elizabeth Denieffe (nee Hoban) and Greg’s mother were not best pleased: especially Elizabeth, her younger brother going to war with her brother-in-law: an adventure for sure but one that ended badly for Patrick, who survived the conflict, and carried the burden and the blame.

I have never seen a photograph of my great-uncle: he has no known grave; his death appears to have gone unreported in local or national newspapers in Ireland and there is as yet no memorial in his home county on which he is remembered (although there is talk of one in the future). The only record of his sacrifice is that his name appears on the Tyne Cot Memorial, West-Vlaanderen in Belgium, not far from where he died.

Officially known as the Third Battle of Ypres, ‘Passchendaele’ became infamous not only for the scale of casualties, but also for the mud. It lasted from 31 July to 10 November 1917. Ypres was the principal town within a salient (or bulge) in the British lines and the site of two previous battles. Within this salient and time frame, some of the fighting is known under their own battle names. The Battle of Langemarck (the second Allied attack of the Passchendaele offensive) lasted three days, 16 – 18 August and in the weeks that followed, a number of skirmishes occurred in the same area. It was during one of these, on the 13 September, that Greg Hoban lost his life. The following is how the three days from 12 to 14 September 1917 are described in The Irish Guards in The Great War, Volume II, The Second Battalion (1923), edited by Rudyard Kipling:

The Battalion went up in the afternoon of the 12th September, none the better for a terrific bombardment an hour or two before from a dozen low-flying planes which sent everyone to cover, inflicted twenty casualties on them out of two hundred in the neighbourhood, and fairly cut the local transport to bits. The relief, too — and this was one of the few occasions when Guards’ guides lost their way — lasted till midnight.

Six platoons had to be placed in the forward posts above mentioned, east of the little river whose western or home bank was pure swamp for thirty yards back. Says the Diary: “This position could be cut off by the enemy, as the line of the stream gives a definite barrage-line, and, if any rain sets in, the stone bridge would be the only possible means of crossing.” A battalion seldom thinks outside of its orders, or someone might have remembered how a couple of battalions on the wrong side of a stream, out Dunkirk way that very spring, had been mopped up in the sands, because they could neither get away nor get help. Our men settled down and were unmolested for three hours. Then a barrage fell, first on all the forward posts, next on the far bank of the stream, and our own front line.

The instant it lifted, two companies of Wurtembergers in body-armour rushed what the shells had left of the forward posts. Lieutenant Manning on the right of Ney Wood was seen for a moment surrounded and then was seen no more. All posts east of Ney Copse were blown up or bombed out, for the protected Wurtembergers fought well. Captain Redmond commanding No. 2 Company was going the rounds when the barrage began. He dropped into the shell-hole that was No. 6 post, and when that went up, collected its survivors and those from the next hole, and made such a defence in the south edge of Ney Copse as prevented the enemy from turning us altogether out of it.

Most of the time, too, he was suffering from a dislocated knee. Then the enemy finished the raid scientifically, with a hot barrage of three quarters of an hour on all communications till the Wurtembergers had comfortably withdrawn. It was an undeniable “knock,” made worse by its insolent skill.

Losses had not yet been sorted out. The CO, wished to withdraw what was left of his posts across the river — there were two still in Ney Copse — and not till he sent his reasons in writing was the sense of them admitted at Brigade Headquarters. Officer’s patrols were then told off to search Ney Copse, find out where the enemy’s new posts had been established, pick up what wounded they came across and cover the withdrawal of the posts there, while a new line was sited.

In other words, the front had to fall back, and the patrols were to pick up the pieces. The bad luck of the affair cleaved, as it often does, to their subsequent efforts. By a series of errors and misapprehensions Ney Copse was not thoroughly searched and one platoon of No. 3 Company was left behind and reported as missing. By the time the patrols returned and the Battalion had started to dig in its new front line it was too light to send out another party. The enemy shelled vigorously with big stuff all the night of the 13th till three in the morning; stopped for an hour and then barraged the whole of our sector with high explosives till six. During this, Lieutenant Gibson, our liaison officer with the French, was wounded, and at some time or another in a lull in the infernal din, Sergeant M ‘Guinness and Corporal Power, survivors of No. 2 Company, which had been mopped up, worked their way home in safety through the enemy posts.

The morning of the 14th brought their brigadier who “seems to think that our patrol work was not well done,” and had no difficulty whatever in conveying his impression to his hearers. Major Ward went down the line suffering from fever. There were one or two who envied him his trouble, for, with a missing platoon in front — if indeed any of it survived — and a displeased brigadier in rear, life was not lovely, even though our guns were putting down barrages on what were delicately called our “discarded” posts. Out went another patrol that night under Lieutenant Bagot, with intent to reconnoitre “the river that wrought them all their woe.” They discovered what everyone guessed — that the enemy was holding both river-crossings, stone bridge and duckboards, with machine-guns. The Battalion finished the day in respirators under heavy gas-shellings.

The ‘Brigadier’ seems like a nice chap!

The truth is that the 2nd Batt., Irish Guards earned two Victoria Crosses in that skirmish.

For my American friends who may have come across the name Hoban before, I can help you connect with your own history.

James Hoban was born and raised in Ireland and, in 1792; Hoban won the competition for the design of the White House. The design itself is very obviously based on what is now the House of the Oireachtas (the Irish Parliament), Leinster House. Both have a triangular pediment supported by four round columns, with three windows on multiple levels underneath, and four on either side, with alternating round and triangular crowns above each window. Interestingly, from my point of view, James Hoban was a Kilkenny man. Was he a relative? Depends on the incumbent!

As a final tribute to Greg Hoban, I would like to post the last four lines of To My Daughter Betty, The Gift of God a poem by Irish poet and WW1 casualty Tom Kettle:

Know that we fools, now with the foolish dead,

Died not for flag, nor King, nor Emperor,—

But for a dream, born in a herdsman’s shed,

And for the secret Scripture of the poor.

Ar dheis Dé go raibh a anam (May his soul be seated on God’s right hand).

Greg, what a wonderful piece. Your pride and sorrow are both evident, in equal measure, and rightly so. The Irish Guards have a wonderful history, and your family played a small but intrinsic part in forging it. I shall raise a glass to Gregory Hoban at dinner tonight. Qui Separabit.

Hear, hear – I agree with William, I think many of us will raise a glass for Greg’s great-uncle today.

A good story, and sad.

Great read thanks Greg dad had filled me in before but it’s good to read it again . Ar dheis Dé go raibh a anam

Greg – please contact me on emjayba@ymail.com I am sat now in Ypres. Today I’ve been to where I believe Greg was killed in action. I have his regimental records and a picture of him. My Grandfather was Andrew Hoban. Greg’s brother. Regards. Mick Hoban

Greg congratulations, your grand Uncle was also mine, and my cousin Michael Hoban, son of Andrew Hoban 91 years of age and still hale & hearty in England , has visited Tynecot Memorial on Gregs Anniversary this week of the 13/09/2017 . Your dad Jim always talked to Bessie and I of all his trips to the rowing in England when he visited you in the summer . Best wishes Eleanor Doyle Gowran , Kilkenny .

Hi greg, just came accross this article by chance and absolutely loved it. I am your cousin, living in cork. I am Johanna Denieffes daughter Oonagh. (your first cousin) I was thrilled when I started to read the above, it was so interesting and I couldnt read it quickly enough. Have you any information on the family tree or have you any more history of the denieffe/hoban family. I would love to get a copy of anything you have. I have been trying to gather information on and off for years but have not had the time to settle down to it.

Love to hear from you,

oonaghallen@gmail.com