17 February 2026

By Bill Miller

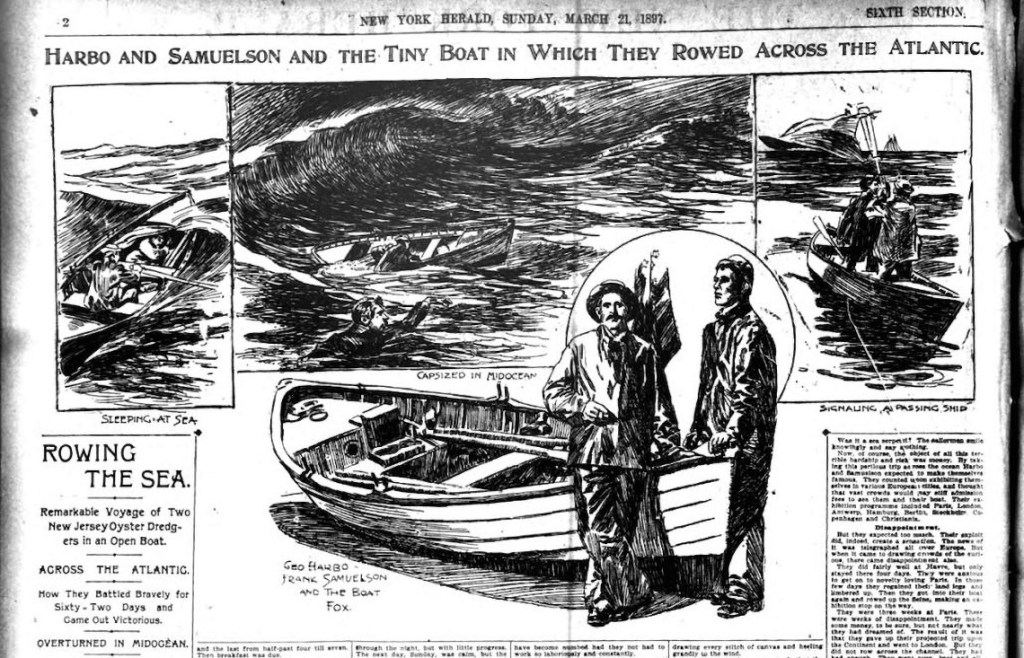

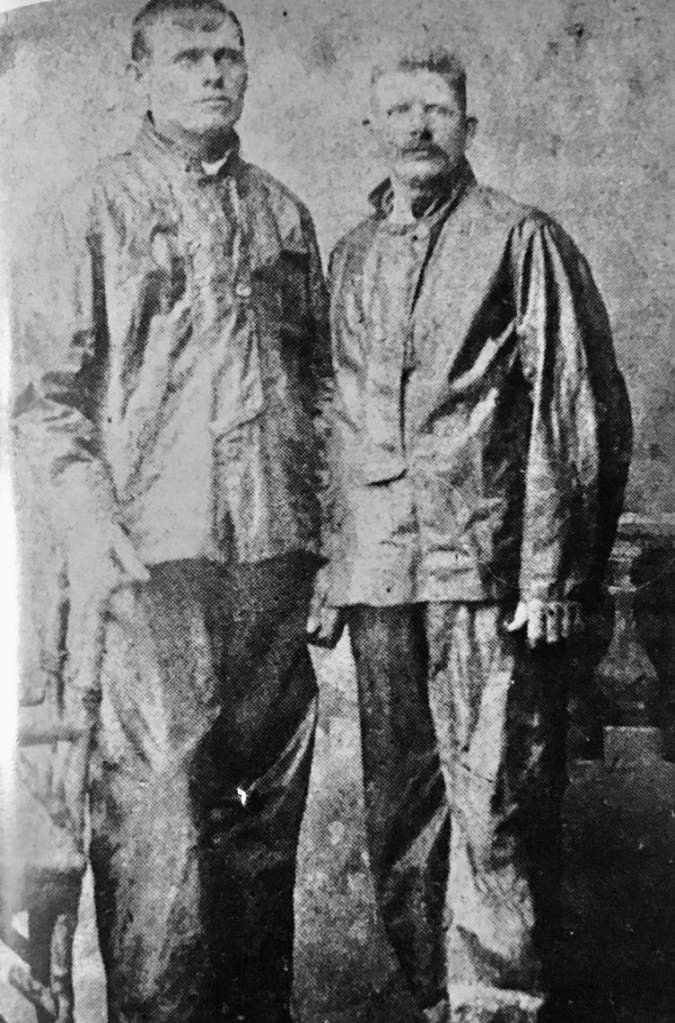

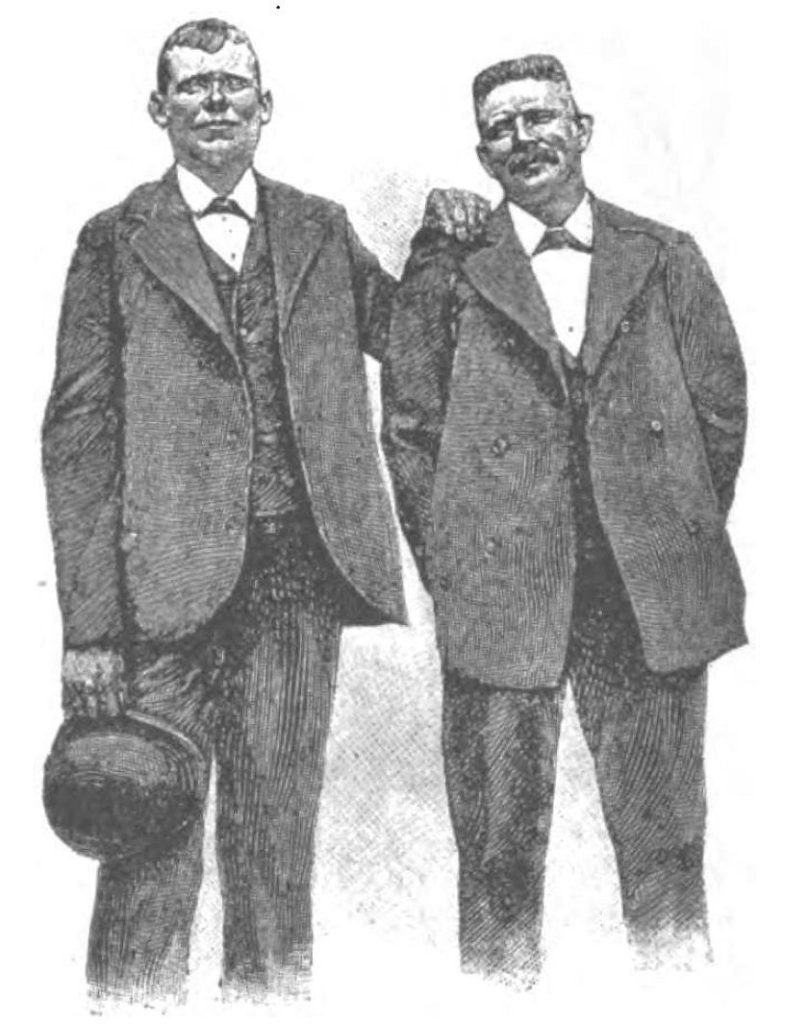

Ocean rowing today is very popular. It has turned into racing across the Atlantic from the Canary Islands to the West Indies – 2,530 nautical miles (2,900 statute miles) and other courses. The race was founded in 1997 by Sir Chay Blyth. Chay with partner John Ridgway crossed the Atlantic from Cape Cod to Ireland in 1966. However, the first crossing was 70 years earlier. Two Norwegian-born Americans, George Harbo and Frank Samuelsen, crossed in June 1896. The pair left Battery Park, Manhattan on 6 June 1896, arriving on the Isles of Scilly 55 days and 13 hours later, having covered 3,250 nautical miles (3,740 statute miles). Then they continued to row to Le Havre, France.

I became interested in the Harbo-Samuelsen crossing after I purchased a beautiful album commemorating their feat. At the Twin Lights Museum in Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey, there is a museum with oil paintings showing their Atlantic crossing story. The album has sixteen double-matted pages. Seven show copies of the museum paintings. Between the seven images are hand-written copies of their log.

The story starts with two Norwegian immigrants who meet and become friends while oyster dredging along the New Jersey shore.

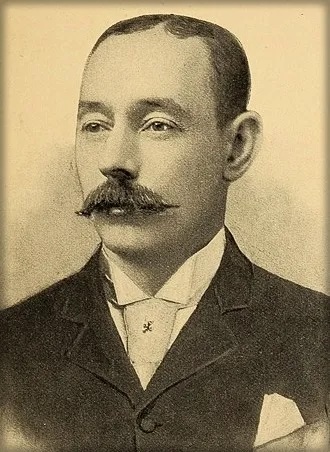

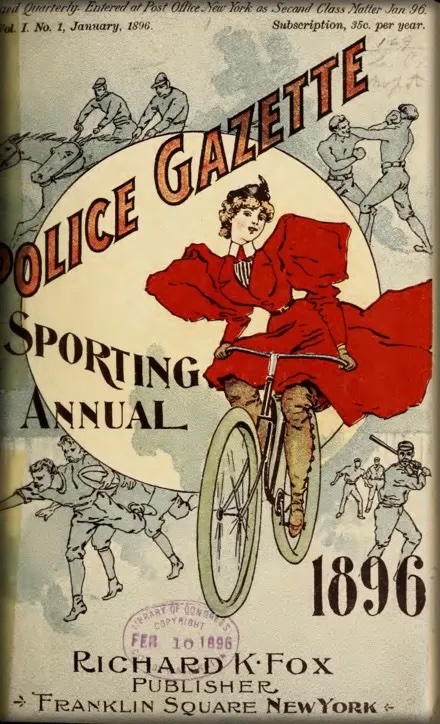

The inspiration for their scheme came from Richard Fox, publisher of the National Police Gazette. He had backed previous schemes for publicity for the Gazette. Fox allegedly offered a prize of $10,000 (roughly $300,000 today) to the first men to row across the Atlantic, although no sources exist that confirm that this money was ever offered by Fox to Harbo and Samuelsen.

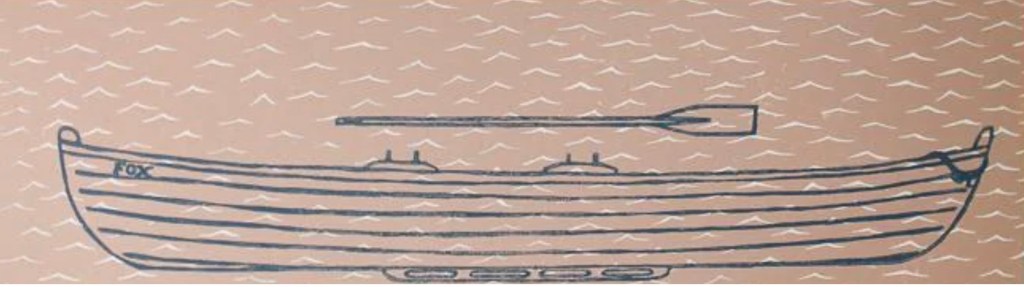

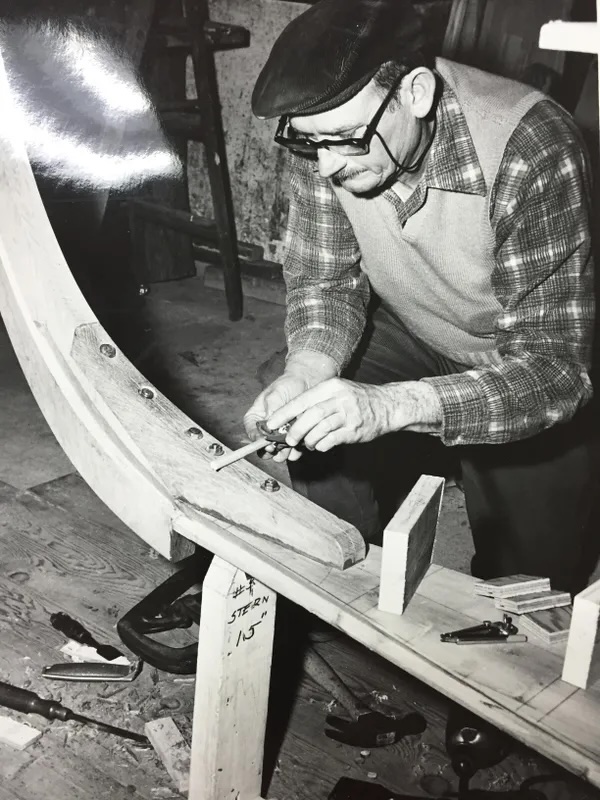

Using their life savings, Harbo and Samuelsen had an 18-foot clinker dory built with water-resistant cedar sheathing. It included a couple of watertight flotation compartments, two rowing benches, and rails to help them right it if capsized––a feature that saved their lives in mid-ocean. The boat displayed the American flag and was named Fox in honor of the editor. With a compass, a sextant, a copy of the Nautical Almanac, oilskins and extra sets of oars, they set out.

Here are Harbo’s images and descriptions of the journey:

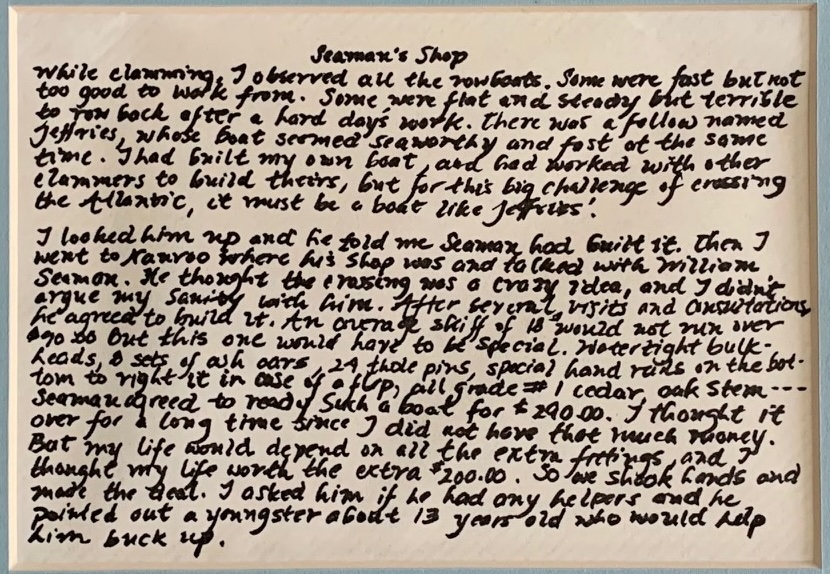

Seaman’s Shop

While clamming, I observed all the row boats. Some were fast but not too good to work from. Some were flat and steady but terrible to row back after a hard day’s work. There was a fellow named Jeffries, whose boat seemed seaworthy and fast at the same time. I had built my own boat and had worked with other clammers to build theirs, but for this big challenge of crossing the Atlantic, it must be a boat like Jeffries’.

I looked him up and he told me Seaman had built it. Then I went to Nauvoo where his shop was and talked with William Seaman. He thought the crossing was a crazy idea, and I didn’t argue my sanity with him. After several visits and consultations, he agreed to build it. An average skiff of 18’ would not run over $90.00. But this one would have to be special. Watertight bulkheads, 8 sets of ash oars, 24 thole pins, special hand rails on the bottom to right it in case of a flip, all grade #1 cedar, oak stem— Seaman agreed to ready such a boat for $290.00. I thought it over for a long time since I did not have that much money. But my life would depend on all the extra fittings and I thought my life worth the extra $200.00. So we shook hands and he made the boat. I asked him if he had any helpers and he pointed out a youngster about 13 years old who would help him buck up.

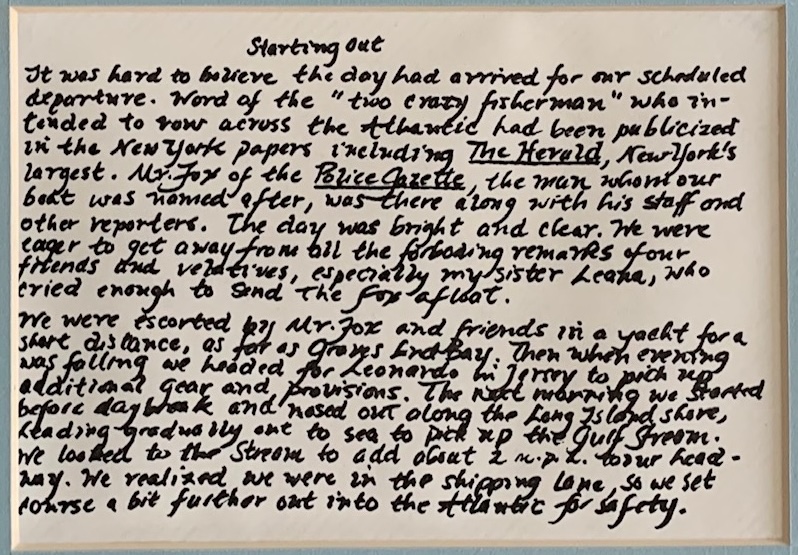

Starting Out

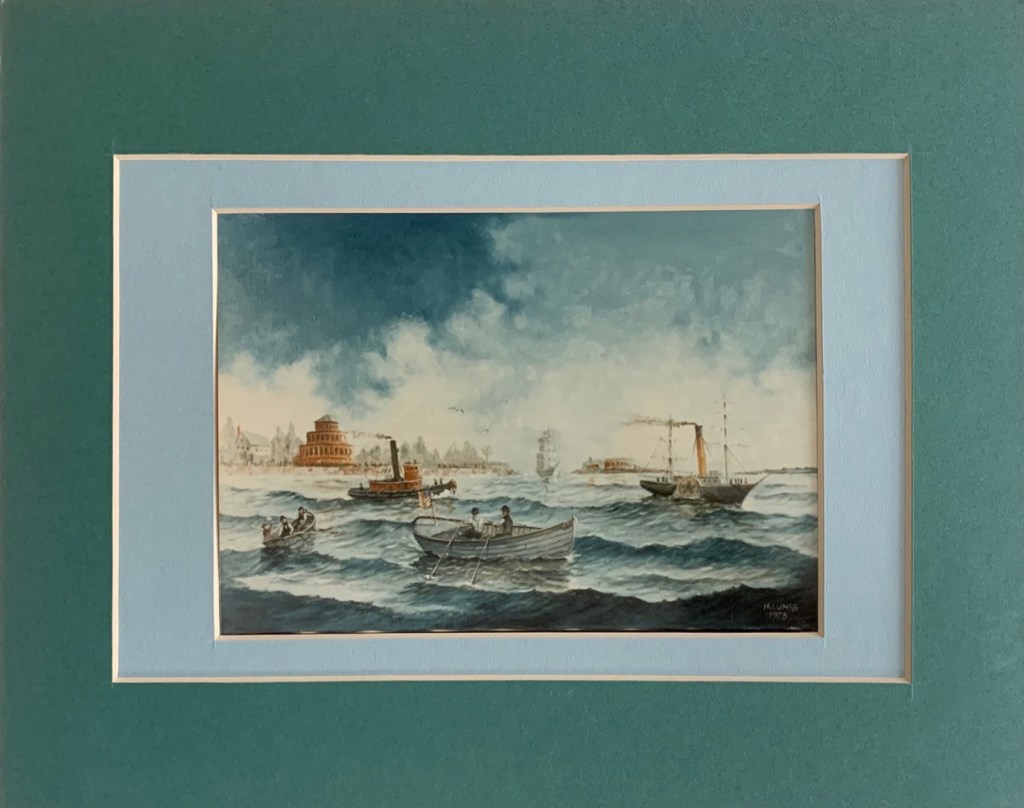

It was hard to believe the day had arrived for our scheduled departure. Word of the “two crazy fishermen” who intended to row across the Atlantic had been publicized in New York papers including The Herald, New York’s largest. Mr. Fox of the Police Gazette, the man whom our boat was named, was there along with his staff and other reporters. The day was bright and clear. We were eager to get away from all the forboding remarks of our friends and relatives, especially my sister Leana, who cried enough to send the Fox afloat.

We were escorted by Mr. Fox and friends in a yacht for a short distance, as far as Graves End Bay. Then when evening was falling we headed for Leonards in Jersey to pick up additional gear and provisions. The next morning we started before daybreak and nosed out along the Long Island shore, heading gradually out to sea to pick up the Gulf Stream. We looked to the Stream to add about 2 m.p.h. to our headway. We realized we were in the shipping lane, so we set course a bit further out into the Atlantic for safety.

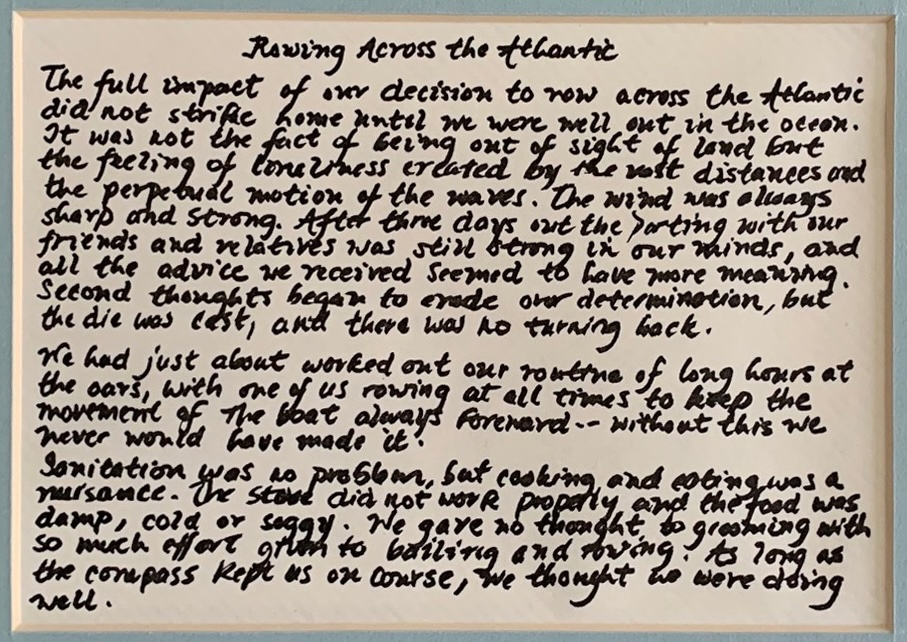

Rowing Across the Atlantic

The full impact of our decision to row across the Atlantic did not strike home until we were well out in the ocean. It was not the fact of being out of sight of land but the feeling of loneliness created by the vast distances and the perpetual motion of the waves. The wind was always sharp and strong. After three days out the parting with our friends and relatives was still strong in our minds, and all the advice we received seemed to have more meaning. Second thoughts began to erode our determination, but the die was cast, and there was no turning back.

We had just about worked out our routine of long hours at the oars, with one of us rowing at all times to keep the movement of the boat always foreward… without this we never would have made it.

Sanitation was no problem, but cooking and eating was a nuisance. The stove did not work properly and the food was damp, cold and soggy. We gave no thought to grooming with so much effort going to bailing and rowing. As long as the compass kept us on course, we thought we were doing well.

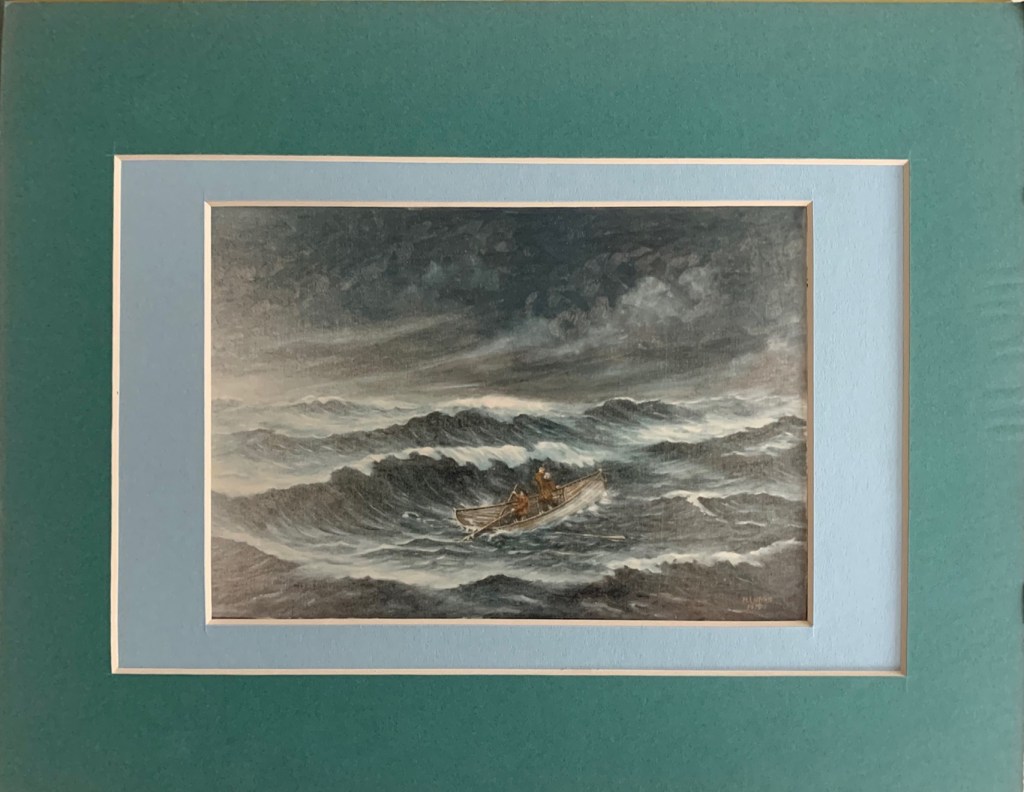

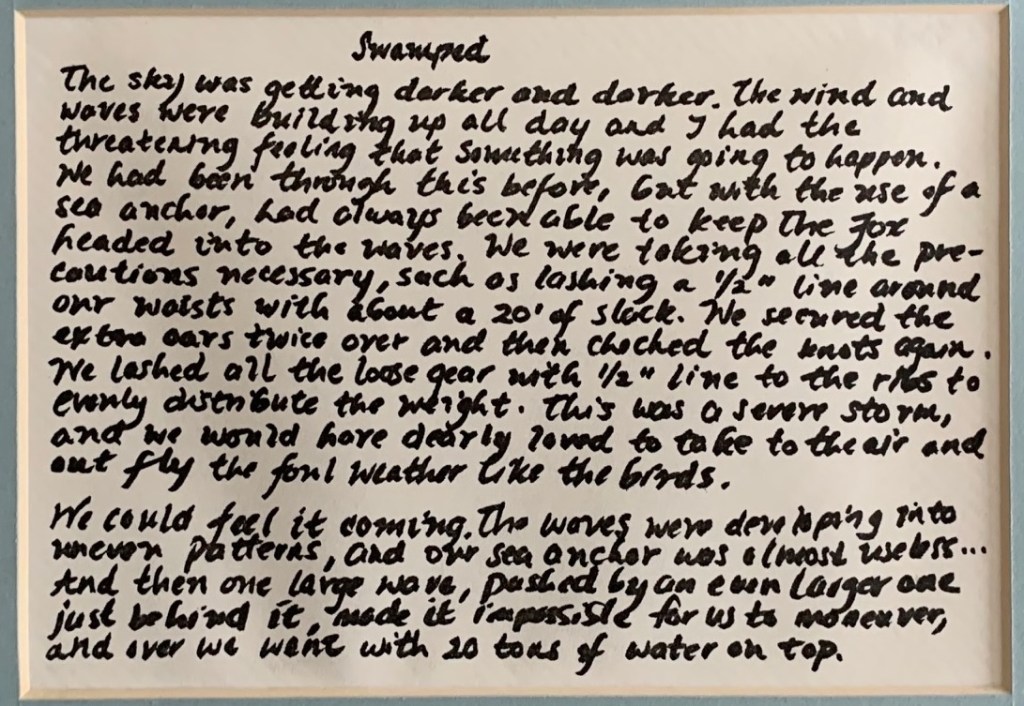

Swamped

The sky was getting darker and darker. The wind and waves were building up all day and I had the threatening feeling that something was going to happen. We had been through this before, but with the use of a sea anchor, had always been able to keep the Fox headed into the waves. We were taking all the precautions necessary, such as lashing a ½” line around our waists with about 20’ of slack. We secured the extra oars twice over and then checked the knots again. We lashed all the loose gear with ½” line to the ribs to evenly distribute the weight. This was a severe storm, and we would have dearly loved to take to the air and out fly the foul weather like the birds.

We could feel it coming. The waves were developing into uneven patterns, and our sea anchor was almost useless… And then one large wave, pushed by an even larger one just behind it made it impossible for us to maneuver, and over we went with 20 tons of water on top.

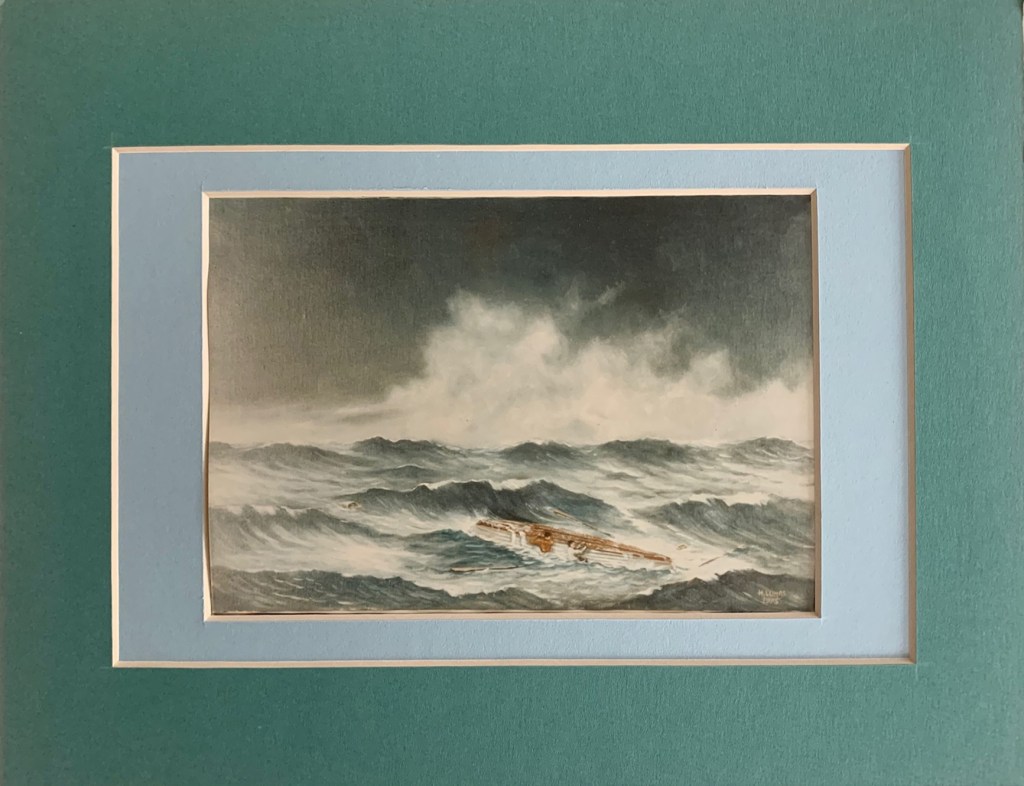

Righting the Boat

The worst had happened and we were still alive! It was almost a relief to be in the water after the days and nights of apprehension. Although it was July. There is no doubt that we owe our lives to Mr. Seaman for putting the hand rails on the bottom of the skiff. It was almost like reaching out and grasping his strong capable hand as we clutched to those rails he had designed. Because of the ½” line tied from out waists to the boat, we had no trouble staying with the Fox. The boat righted very easily with our combined effort when the waves calmed down slightly, but there was a lot of bailing to do. Fortunately the bucket was secure to the thwart. We did lose our stove and one of the long seats. Everything was soaked but the matches and the log which were kept in the watertight mason jar.

After we were in the boat again, we realized what bad shape we were in. Our heavy clothing was soaked through but it was the only dry protection we had. We rowed on ‘til the clothes began to dry out from the heat of our labor. We had only one hope now — Would a ship sight us and take us on board.

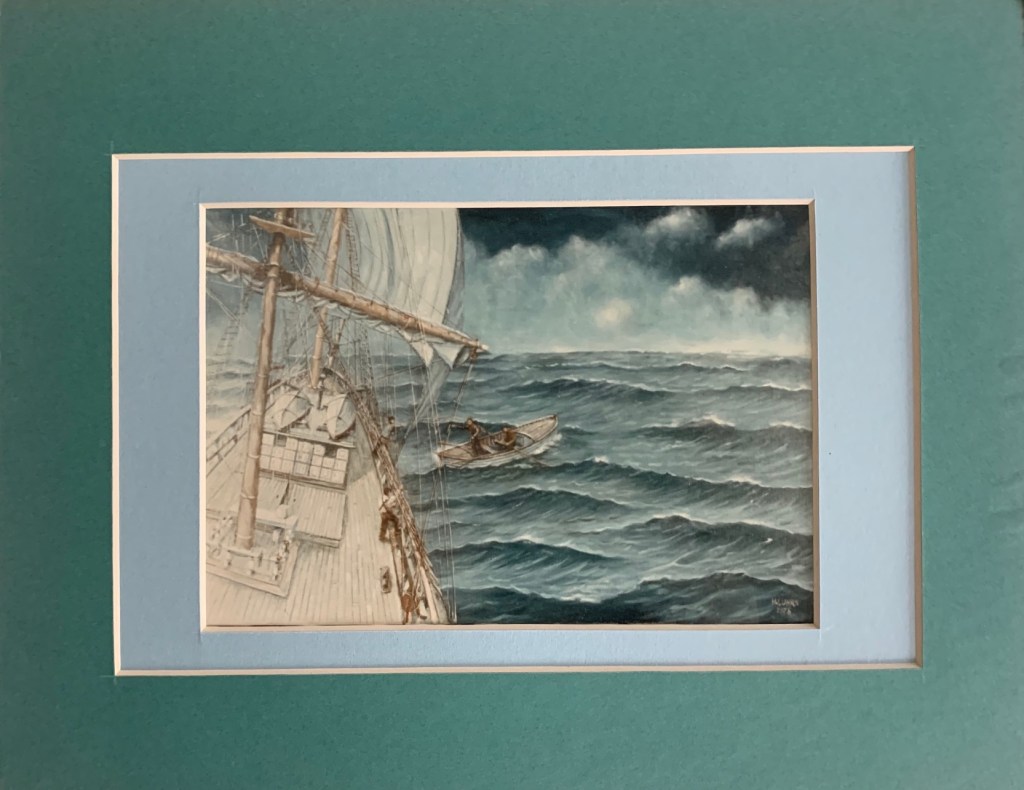

Being Picked Up by The Bark Cito

It was four days after righting our boat that we sighted the Bark Cito of Norway. After seeing us, she made straight for us with the impression that we were castaways. Although the bark was headed for New York, I had no lessening of joy on seeing her coming on. Our food and water were almost gome. We had eaten nothing hot for five days; everything was wet and damp, including our spirits. We maneuvered to the lee side for the pick-up. She had a full cargo and the sides were low in the water. That made it easy for us to get on board after we made the Fox fast. We were well fed by this kind crew. We slept in dry bunks, cleaned up, and had a hot breakfast. Our stores were replenished including fresh water. The men thought it incredible that we made it so far and begged us not to press our luck. They were headed for New York and would gladly take us along, boat and all, free of charge. What a temptation. But the good food and a night’s rest plus every minute spent on board would mean that many more miles to retrace with more rowing. The captain gave us our latitude and longitude and a letter saying he had picked us up. At 5:00 pm we were on our way again with deepest forboding of the crew, some of whom, by the way, came from my home in Norway.

Harbo and Samuelsen landed in Isles of Scilly, but their destination was Le Havre, so they set off for France.

Arriving in Le Havre

On August 7, 1896 we sailed joyfully into Le Havre harbor. At last, after 62 days and nights! Now those long nights with the relentlessly tossing boat in the damp, chilly darkness, were behind us. The long haul was over.

The US Consul of the Scilly Islands, John Banfield, had notified the French of our approach, but we took longer to cross the Channel than the five days he had estimated, and that explains the small crowd that greeted us. A Norwegian sailor translated the welcome to us. Our first concern where was the man with the money. We were reassured that the money would be awarded in due time, and would be in American dollars.

Everyone was extremely friendly and astounded that we had rowed all the way across the Atlantic, especially the men with a knowledge of the sea.

Richard Fox came to Paris, and at a dinner held in honor of the Atlantic voyagers, handed each rower a gold medal. Samuelsen and Harbo, however, never received any prize money, nor gained any fame and fortune on the lecture circuit.

Editor’s Note: In 1998, David W. Shaw published Daring the Sea: The True Story of the First Men to Row Across the Atlantic Ocean about George Harbo and Frank Samuelsen voyage over the Atlantic.

I am puzzled as to how they could have accomplished this feat with enough food and water on board. Seems impossible to me to do that without support.