29 January 2026

By Tim Koch

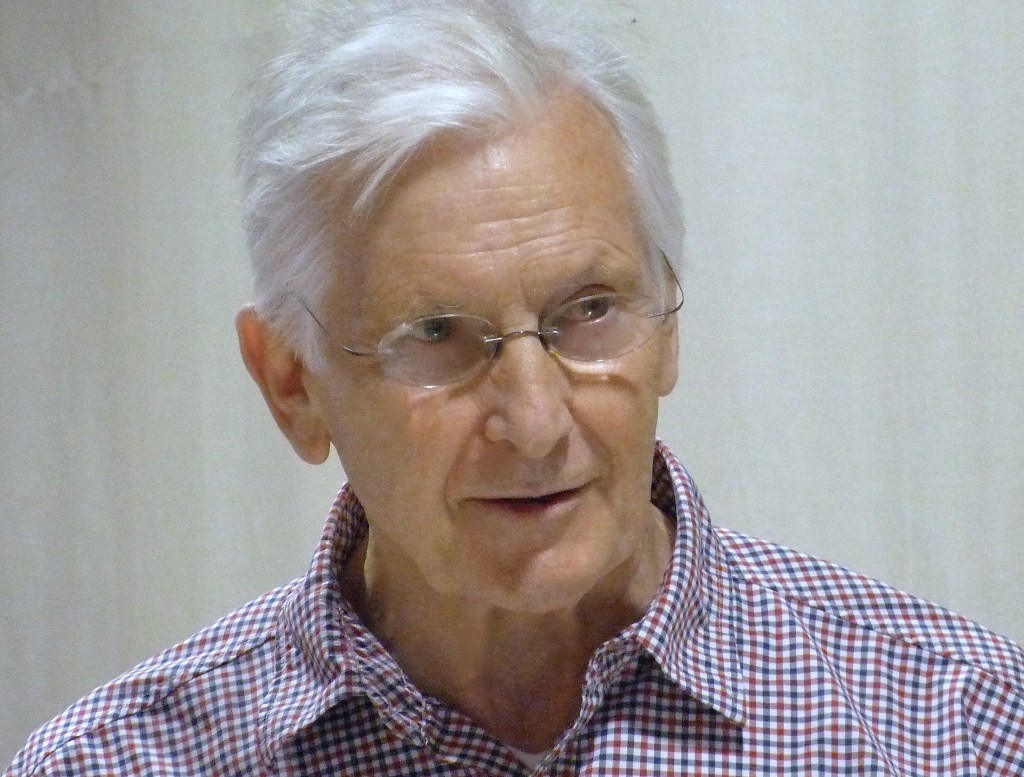

Tim Koch attempts to pay a suitable tribute to an old friend.

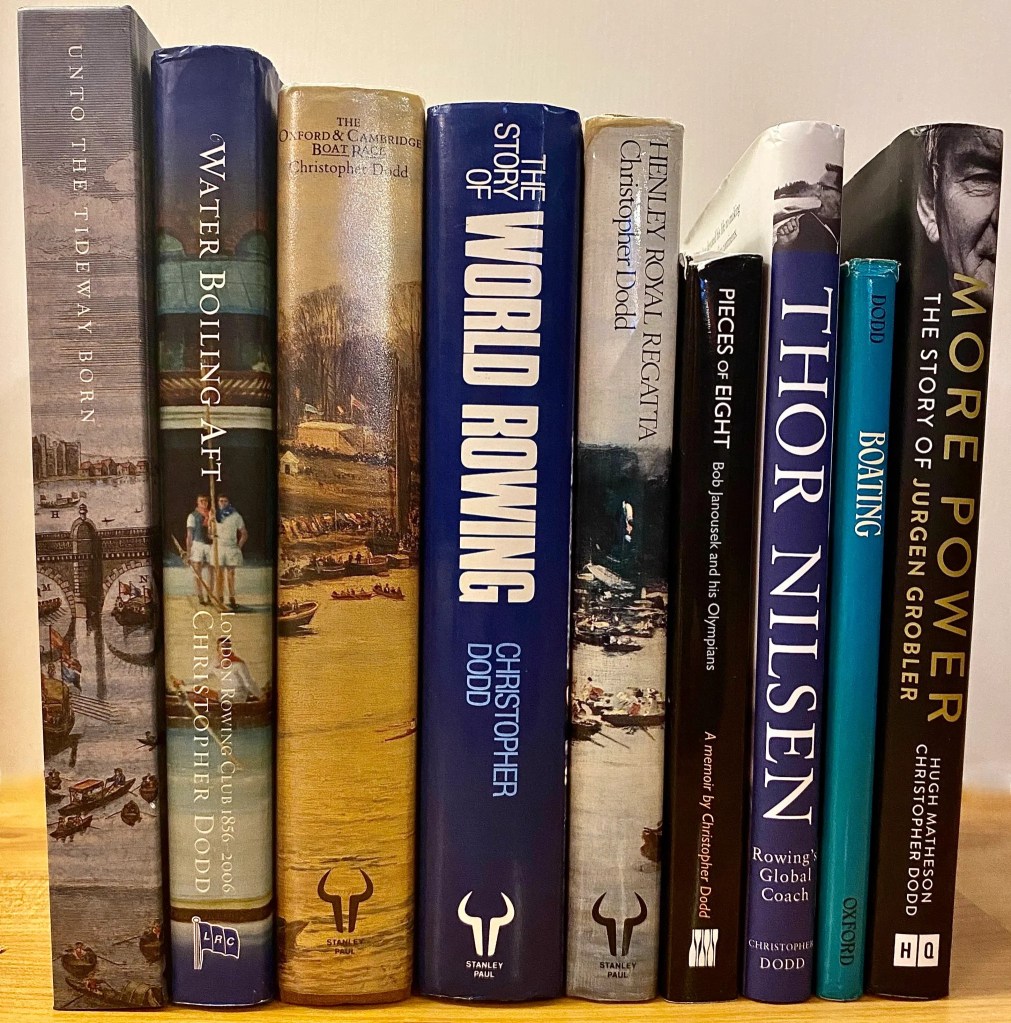

Over the last fifty years, the death of one of rowing’s most respected journalists, authors, historians and editors would have automatically called for an obituary from (depending on the era) the typewriter, word processor or laptop of Chris Dodd.

Sadly, with Chris’ passing there are few who can properly fill his place, few who can confidently be given the task of capturing a full life in a deft piece of writing peppered with wry humour, telling anecdotes and quiet authority.

The world of rowing journalism that Chris first entered into in 1970 is best described in his obituary of Geoffrey Page in the Guardian of 6 April 2002. It is a piece of writing that reveals the skill of its author as well as the character of its subject.

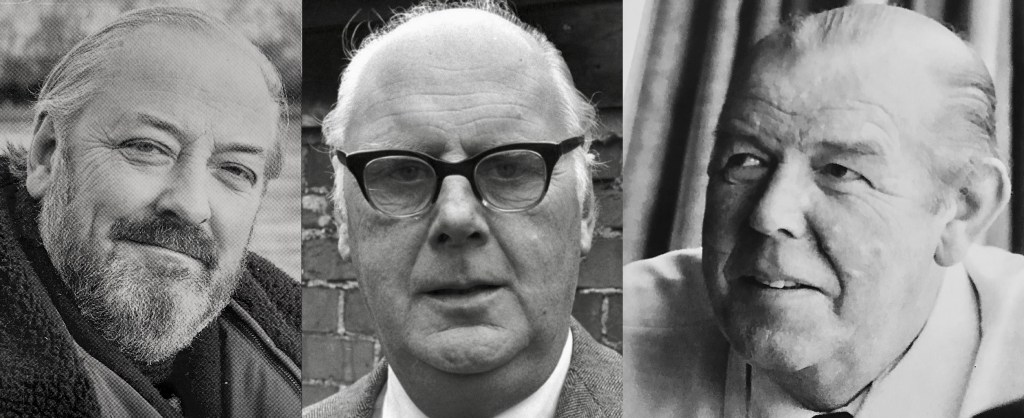

Geoffrey Page… was the last survivor of a small band of rowing correspondents who were heavies in every sense of the word. When I began writing on the subject for the Guardian… I was apprenticed to the Sunday Telegraph’s Page, the Daily Telegraph’s Desmond Hill and the Sunday Times’ Richard Burnell, eccentric fanatics who were masters of the stopwatch, judges of fine blade-work, thorns in the side of selectors, and barstool coaches par excellence. They were also a discerning panel on wines, beers and firewaters of the world, and could Hoover a buffet like no one else. Their arguments were radical, and they seldom agreed about anything…Early rowing correspondents came from a school in which the rating watch ruled, and the prose was usually in the language of insiders. They were critics, not interviewers or profile writers…

Although like Page, Hill and Burnell, Chris was privately educated and was equally not adverse to a visit to a buffet or bar, I think that it is important that he came from a later generation, that he was a professional newspaper man, and that his rowing career was considerably less distinguished than that of the three colleagues that he was apprenticed to. In particular, the latter relieved him of the seeming obligation to coach from a high seat in licensed premises and to have unyielding opinions on selection, technique and training.

Not being a bigot on rowing matters made Chris’ writing more accessible. The journalism of the older generation of rowing correspondents was not Chris’ style, unlike them he did write profiles and conduct interviewsand did avoid the overuse of “the language of insiders”.

As a result, his prose appealed to all types, from year-round oar pullers, to long retired third-eighters, to those non-rowers whose aquatic interest was only aroused by the annual University Boat Race. As Göran R Buckhorn noted in 2011, (Chris’) writing always carries a substance while still having an easy-going way about it.

In a telling review of More Power, a 2020 biography of Jurgen Grobler that Chris wrote with Hugh Matheson, Oli Rosenbladt wrote on row2k:

As with Dodd’s other books, the writing is keen, well-balanced between telling anecdotes (always a key driver in Dodd’s books), analysis, and a terrific sense of how the pieces fit together historically. Likewise, Dodd and Matheson strike a strong balance between technical details that rowers and coaches of any stripe will appreciate, with enough storytelling chops to draw in a more general reader.

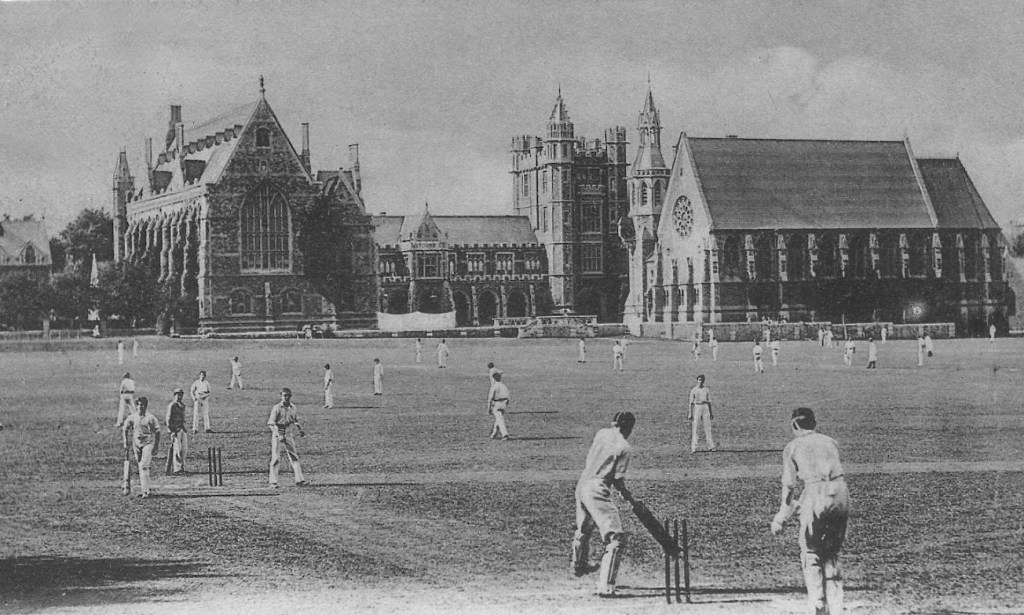

Christopher John Dodd was born in 1942 in Bristol, south-west England, where his father worked in insurance. For his secondary education, he was sent to Bristol’s Clifton College, an independent boarding and day school, where he was a day boy at East Town House. Historically Clifton was said to be “less concerned with social elitism” than other such educational establishments, so it was probably a good starting place for a future journalist on the liberal-left Guardian newspaper.

After beginning as a schoolboy cox, “Doddo” progressed to the stroke seat of Clifton’s second eight. He later remembered those pre-health and safety days for the school’s alumni magazine:

The club rowed out of Bristol Ariel’s boathouse across the city from the school, so going rowing three times a week was a relief from school rules as well as a legitimate way of avoiding boredom on the cricket field. What’s more, travel to the polluted Avon in St Anne’s was by way of an old laundry van fitted with school benches. The journey through central Bristol was often conducted with the rear door open and the sound of songs to entertain the citizenry.

In March 2025, Chris recalled his leadership of The Great School Tuck Shop Mutiny for heartheboatsing.com:

Our coach promised trials to us all ‘possibles’ for a seat in the ‘probables’, but in the event the No. 7 seat Richard Hunt and myself at stroke did not receive a trial. At a steamy meeting in the school tuck shop sipping Coke and chewing iced buns the assembled crew decided to challenge our first eight to a grudge race during the season… (At Salford Regatta) we finished the day by beating the first eight in our private tuck shop challenge. Job done!

Perhaps this gave Chris some insight when he later covered the 1987 Oxford Boat Race Mutiny.

After finishing at Clifton in 1959, Chris went up to Nottingham University. Initially he rowed there but soon gave up early mornings on the River Trent for late nights in smoke filled rooms as editor of the student newspaper, The Gongster.

After university in 1965, Chris joined the Guardian as a sub-editor. He was interviewed for the post in a Manchester pub. He later said that he did not know whether he should drink, abstain or buy a round. As a staffer, his main job was layout, design and section editing in the features department, but he also worked in the sport and city departments.

Called The Manchester Guardian until late 1959, the Guardian was largely based in London by the time Chris joined it – though it retained offices in Manchester. He once told me of seeing the by then defunct loft for messenger pigeons that still existed on the roof of the Guardian’s Cross Street, Manchester, offices. An old hand told him that the best way to ensure that the birds flew home quickly was to have food and a mate waiting. This probably worked for the journalists as well.

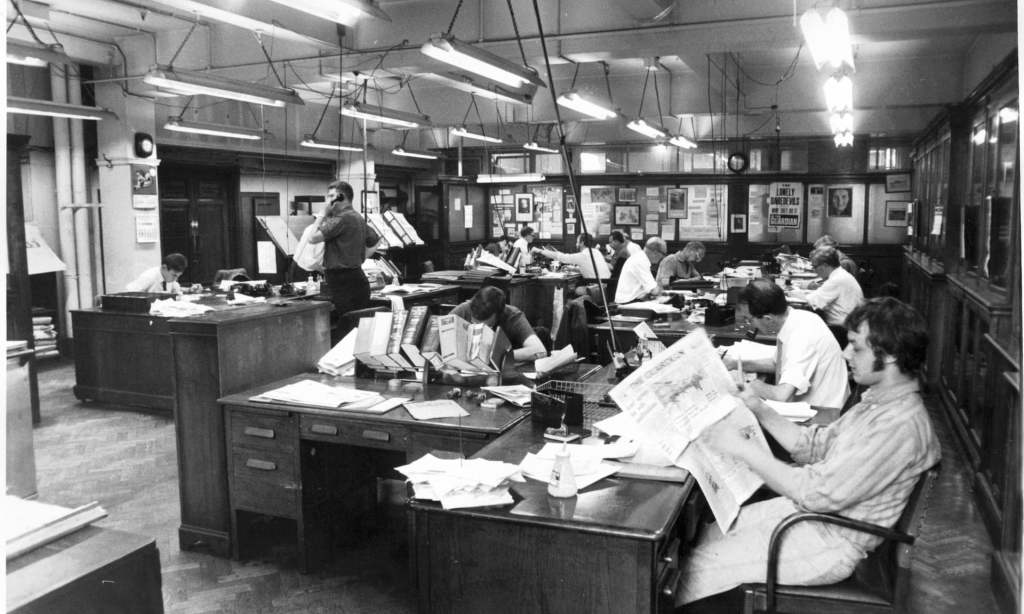

Chris later recalled his early journalistic days when all national newspapers had their printing presses in the basements of their offices, things that caused the building to vibrate when they ran:

I was fortunate to begin my subbing in the Guardian’s old Cross Street office in Manchester… a proper five-storey purpose-built Victorian newspaper building with a mahogany corridor giving access to leader writers’ offices. A closed door signalled “no disturbance” while the occupant composed, sometimes with pen on paper rather than typewriter. The building smelt of damp paper and throbbed just like a liner leaving port, lights twinkling in the canteen on the top floor, presses starting up and tuning to a distant rumble, yellow vans fussing round the cargo doors like tenders.

In Chris’ first 22-years at the Guardian, the printing process used was “hot metal.” This was the method used to set the pages and create the plates from which the paper was printed which involved casting the words and headlines out of molten lead. The result was that sub editors like Chris became deft at reading upside-down and back-to-front type. When the process ended in 1987, he reminisced:

To experience a composing room at full stretch was a miracle and a wonder of skill. Speed and flexibility were of the essence, and the nightly operation of the Farringdon Road (London) composing room, known as the engine room on good days or the underworld – or even the decomposing room on bad – was something to behold.

Chris began writing about rowing for the Guardian almost accidentally when in 1970 he interviewed the new British national rowing coach from Czechoslovakia, Bohumil “Bob” Janousek. In his semi-biography of Janousek, Pieces of Eight (2012), Chris explained:

I first met (Janousek) in an Oxford Street pub next door to the language school where he spent his afternoons learning English. I was a sub-editor in the features department of the Guardian and a request from the sports editor to write some pieces about rowing coincided with Janousek’s arrival on the scene. We struggled to understand each other for an hour… But our meeting was also the start of an adventure. We were both outsiders on the British rowing scene, and we were both set on finding the inside.

We now know that both succeeded spectacularly well.

To understand how much work there was for a rowing correspondent in Chris’ early days, it is instructive to look at figures that exist on the output of his friend and contemporary, Jim Railton, the Times’ rowing correspondent, 1970-1990, even though the Times was probably keener on rowing than the Guardian. In his first year on The Times, Railton had 84 pieces published. By his last full year on the paper, 1989, his annual article count was down to 62, an indication of things to come but still much better than the current sad situation.

In 1991, Chris had a brief encounter with a field of journalism unfamiliar to him when he attended a meeting of the international rowing federation, FISA, in Zagreb in what was then Yugoslavia:

In March 1991, FISA’s annual meeting of all the commissions took place in Zagreb. Having never been to the area, I set off a few days early to explore the city before rowing matters intervened. Hardly had I reached Heathrow, however, when shots were fired in an unheard corner of Croatia… What few realised at the time, including yours truly, was that the countries of fragile Yugoslavia were sliding into a Balkan war. These were the first shots… (My) boss at The Guardian newspaper was delighted to have a man on the ground, and was keen to have a story. That is how I became a war reporter… I can claim to have trod carefully while unravelling very little.

In his memories of covering the so-called Oxford Boat Race Mutiny of 1987 posted on Hear The Boat Sing in 2023, there was an example of both Chris’ old-school journalistic ethics and also of the respect that the rowing world had for him:

Having one day arranged to interview Jonathan Fish, (Oxford’s) American cox, I had a shock when he showed me into his room to find half a dozen mutineers present, both Yanks and Brits. They asked for my advice because they were getting bad press. That was not surprising as their policy seemed to be to keep their lips tight, which allowed newsmen to speculate, indeed almost required us to do so in order to get a story.

I said it would be unethical for me to offer advice even if I had any, because I was an observer, not a player. But, said I, decide what you want to tell the world before calling a press conference and set out your case clearly, point by point. If you level with the press, they’ll print it.

Until perhaps the end of the 1980s, newspapers would routinely pay for their rowing correspondents to travel abroad and this generosity was made full use of by a regular group of aquatic journalists, initially a boys’ club that, stereotypically, enjoyed a drink and a jape. One of the tired and emotional hacks regularly enjoyed drink so much that, as Robert Treharne Jones recalled in 2022, it was often necessary for the rest of us to file copy under Jim’s name after we had put our own pieces to bed.

Lucerne Regatta was a popular destination, notably in the 1990s when the regatta organising committee was particularly generous with its hospitality. Later, the annual Geoffrey Page Memorial Gin & Tonic Party at Page’s favourite Lucerne hostelry, the Hotel des Alpes, was spoken of wistfullyby regular attendees. Here the British Association of Rowing Journalists’ toast would be given – “I could drink that!”

Of a trip to Egypt to cover the so-called Nile Boat Race, a publicity stunt run by the Egyptian Tourist Board between 1970 and 1983, Chris remembered:

Jim (Railton) and I held a grudge against the New York Times correspondent, whom we had met at Heathrow during a five-hour delay before take-off… One evening, Jim invited the Oxford crew in his best Egyptian voice to come to our five-star hotel to be interviewed for a prestigious TV programme. They duly appeared… and we all sat around the lobby waiting for the TV crew. When it never appeared, Jim invited all to the bar and ordered cocktails. It was a very good and long evening – all charged to the room of the New York Times.

The titles of just a few of Chris’ articles are listed on his website and the online Guardian archive can bring up 48 of his pieces for the paper published between 2001 and 2024. The obituaries in particular are worth visiting, not least because they include such gems as: Rowing began a long haul of change during (John) Garton’s reign, much of it in spite of him; At 5ft 3in tall, (Di Ellis) occupied a coxswain’s frame in a world of lofty men and women; The changes in (Penny Chuter’s) ARA job description did not clarify whether each new title indicated promotion or demotion.

One of my favourite examples of Chris’ way with words was in his 1981 book, Henley Royal Regatta:

A young Thames Tradesmen four lost the Wyfolds in 1970 when they were disqualified for bad steering in the dying moments of the final. It was a controversial decision and in gratitude, the stroke attributed a part of the anatomy to the umpire which is very doubtful he possessed.

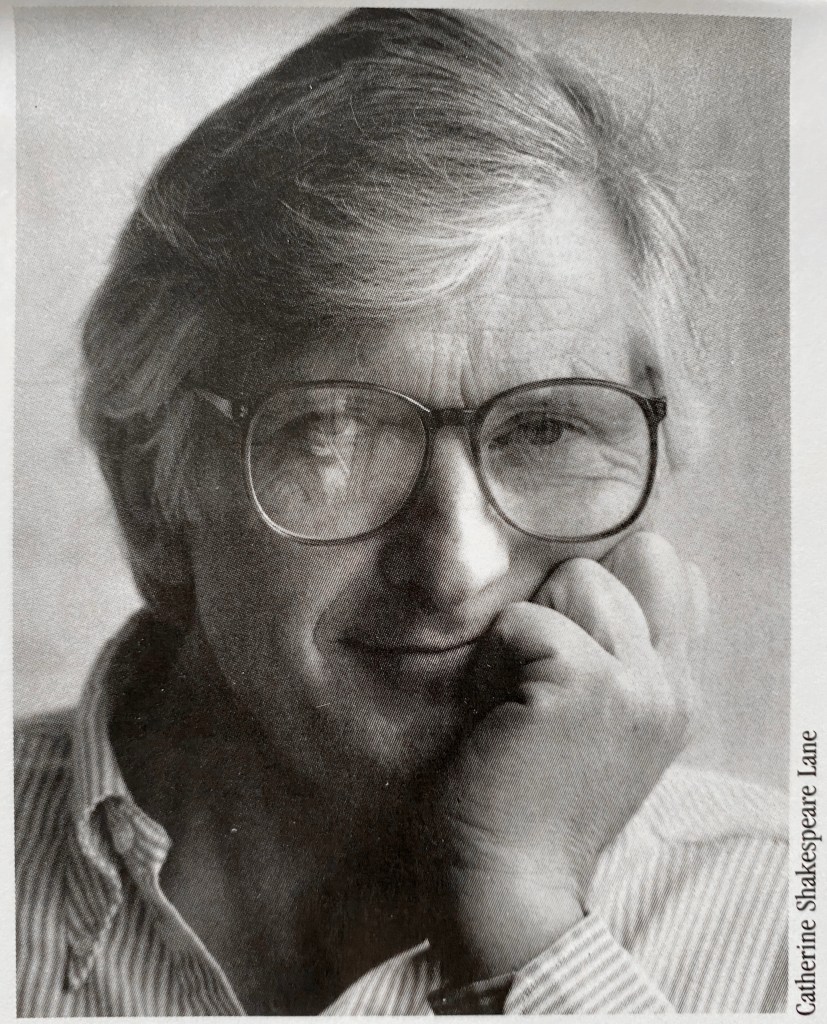

Perhaps as a counter to the declining interest in rowing shown by newspapers, Chris was involved in the foundation of three magazines: World Rowing, RowingVoice and Regatta.

World Rowing was introduced as a paper magazine in time for the 1996 Olympics. Published by FISA, the international rowing federation (Fédération Internationale des Sociétés d’Aviron, now World Rowing), it continues online.

RowingVoice was set up by Chris and the Telegraph’s Rachel Quarrell and had its origins during the 2006 World Rowing Championships. The Voice was very active in its early years and still occasionally posts today.

Regatta (later Rowing and Regatta) began in 1987 as a magazine published for members of the Amateur Rowing Association (now British Rowing). Chris was its editor from the first issue until 2002. In Chris’ fifteen years of editorship, he jealously defended the independence of the magazine against interference by the ARA itself. Notably, Regatta would print letters critical of the Amateur Rowing Association in its own publication. There was a healthy tension between Chris’ journalistic integrity and the ARA’s organisational interests.

On the magazine’s remit, Chris later wrote, There seemed little point in restricting (Regatta) to ARA matters and public relations, for a large portion of the best events are outside the governing body’s jurisdiction. The hierarchy at the time understood that risk there may be, but they got the idea…

Chris kept his day job at the Guardian and was paid a modest honorarium as Regatta editor but, crucially, he was not an employee of the ARA.

One notable editor – publisher conflict occurred in November 1993 when a cover picture referring to an honorary degree given by Imperial College, London, to Bill Mason, its highly successful boat club coach, showed Bill coaching on a cold day wearing a black balaclava. Unfortunately, such headgear was also favoured as a disguise by members of the so-called Irish Republican Army, (IRA) then very active.

Chris later recalled:

Just after the magazine went to press, an IRA bombing atrocity took place, and when a proof of the cover arrived by fax at the ARA office the chairman, Di Ellis, knowing nothing of the Mason story, thought the cover resembled a terrorist. Without consulting the editor, she pulled the issue and announced the decision in a statement to the Press Association…

As (the production editor) sat in the printing house un-stapling thousands of covers while a substitute featuring (Mason in gown and mortarboard) was prepared, I demanded that PA issue a follow-up explaining the circumstances.

However, the incident had a bitter-sweet ending. It was usual practice to send 50 advance copies to the media via first class mail, and these had gone into the post before Di pulled the cover. The tale was then picked up by the Times’ Diary and I told her that “You always wanted good publicity for the ARA.”

Chris presumably believed that no publicity was bad publicity.

Occasionally, Chris wrote droll pieces under the pseudonym “Hammer Smith” in Regatta’s People column and later in RowingVoice. These witty though sometimes controversial articles were often critiques of the sport’s governing body (Chris later wrote that at one time he thought the ARA, an impoverished outfit run by well-meaning amateurs) and commentaries on tensions in high performance rowing circles. After attending a chaotic meeting in 1997 when Leander voted to accept women, Hammer Smith wrote a report, a sample of which is:

The Brilliants’ own committee, a proud body of men elected for “Proficiency in oarsmanship and good fellowship” sat on a soap box before their members in full pinko regalia and orchestrated chaos out of order…

Such irreverence could not last. Chris:

By Sydney (Olympics) 2000, however, Regatta’s People diary was under pressure. As the ARA had grown more professional, so it had become more bureaucratic and sensitive about its image… Some senior managers didn’t get the point of the sometimes irreverent Hammer Smith. Eventually People was killed off and Hammer wandered away…

When what was by then called Rowing & Regatta went from paper to online in April 2020, Chris responded with passion and anger:

The announcement that British Rowing is closing Rowing & Regatta with immediate effect struck a pang in my heart. It is another, if inevitable, blow to rowing journalism and printed journalism, and as the founding editor of Regatta, the news pierced my soul.

The generation wedded to the printed page, of which I am a paid-up member, will raise an eyebrow at one reason cited for the throttling of R&R – that nobody reads it nowadays. That’s because, I hear myself think, the magazine no longer prints anything worth reading. Latterly, pitiful space has been allotted to feeding the hungry with obituaries, readers’ letters, rowing politics or in-depth reporting, not to mention anything so risky as gossip or diary stories.

Despite this criticism, two years later British Rowing awarded Chris their Medal of Honour for his fifty plus years of Outstanding Service to Rowing. In response, Chris said:

Friends, comrades, rowers: I am somewhat astonished as well as flattered to hear that I am to be awarded British Rowing’s Medal of Honour. Flattered because it boosts my ego; astonished because I have sometimes given British Rowing (once the Amateur Rowing Association) a hard time in print.

In 1994, Chris became a freelancer while continuing as the Guardian’s rowing correspondent. In 2004, he moved to the Independent for six years until the paper lost interest in both rowing and its esteemed correspondent…

Chris was an occasional contributor to Rowing News (US) and Rowing MagOZine (Australia). When a digital and, excitingly, also a print magazine, Row360, was founded in Britain in 2014 with the goal of “presenting the sport of rowing in a fresh, exciting, and informative way for a global audience,” Chris was enthusiastically on board as a contributor.

In 2016, Chris adopted the website Hear The Boat Sing (HTBS) as the main online platform for his writing – including the occasional rant. On one or two occasions, HTBS editor, Göran R Buckhorn and I asked Chris to tone down an article as, while Chris was a rowing National Treasure and could probably get away with saying what he liked, an upstart HTBS had to be more circumspect.

Chris once used Hear The Boat Sing to criticise British Rowing for allegedly ignoring his and Hugh Matheson’s 2018 Jurgen Grobler biography, probably because of its examination of the great coach’s East German years (the subject himself had politely refused to cooperate with the authors). BR’s action was strange as it was not a period of Grobler’s life that any biographer could have ignored and Chris and Hugh’s study of this time was understanding of having to operate under an authoritarian regime.

Chris was also involved in what he called “blazerati” activities. He was Chairman of Media for both the 1986 and 1994 World Championships, Chief of Olympic News Service for Rowing at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics and a member of FISA media commission, 1990-2002. In 1986, he was a founding member of the British Association of Rowing Journalists, a groupborn from the frustration among British rowing journalists over the poor facilities and services available to those trying to report on rowing events at home and abroad.

It was, however, Chris’ part in the founding of the River and Rowing Museum in Henley-on-Thames that should have been his greatest legacy. Chris and David Lunn-Rockliffe were key figures who initiated and drove the project to create a dedicated museum celebrating rowing and the River Thames. In his 2011 obituary of Lunn-Rockliffe, Chris explained:

When David was executive secretary of the Amateur Rowing Association (ARA, now British Rowing) in the 1980s, he and I hatched the idea of a rowing museum in a pub near Piccadilly Circus. I, as the Guardian’s rowing correspondent, was motivated by seeing a rowing exhibition at the Los Angeles Olympics and David by his frustration at not being able to deal with historical questions that landed on his desk. In short, we formed a committee and over the next few years prised a site out of Henley town council, discovered a then unknown architect called David Chipperfield and found a generous sponsor in Martyn Arbib…

After four years of playing a central and hands-on role helping getting the “mad project” off the ground, Chris was one of the main people responsible for creating the rowing collection and library from scratch and curating special exhibitions and archives, shaping much of the museum’s content and character before its opening in 1998. In 2019, on the RRM’s 21st anniversary, Chris recalled that:

From the beginning, boats had to be the backbone of the museum’s collection. When construction began, we curators had the luxury of possessing no objects and the teeth-chattering challenge of creating a collection to fill our space from nothing…

One of the earliest and best additions to the collection was the boat used by Oxford in the first University Boat Race which was held in Henley in 1829. Chris later wrote:

(The boat) was liberated from the Science Museum where it was on show in a gallery that was due for a makeover and was moved to Henley in the small hours of a Sunday morning after being craned through a hole in the wall of its old home.

There was a hitch, though, before it was moved, the (Science) Museum had second thoughts about shifting the boat just when it had been designed into the rowing gallery at Henley.

The RRM’s CEO, Jonathan Bryant, called me to his office and asked me what I would do if the promise of this key boat fell through.

“I’d leave a big space with a prominent (notice) accusing the Science Museum of reneging on the agreement,” I told him. “And I would issue a press release trumpeting the situation.”

The Oxford boat arrived on time at the place where it had made history in 1829.

The RRM building was designed by the up-and-coming David Chipperfield and was the Royal Fine Art Commission Building of the Year in 1999 – when it also won the Royal Institute of British Architects National Award. I am sure that these were all well deserved but it seems that the science of architecture did not then know that flat roofs are prone to leaking and need to be very expensively replaced by ones that slope after twenty-five years.

The museum itself won many accolades including being ranked among the world’s top 50 museums by the Times newspaper in 2013. Between 1998 and 2025, the RRM was visited by over two million people and amassed a collection of 35,000 objects.

Sadly, it was not to last and after 27 years the River and Rowing Museum closed for economic reasons in 2025, a cause of enormous sadness to Chris. If there was any justice, a thriving River and Rowing Museum would still exist today and it would display the same epitaph to Chris as that on Sir Christopher Wren’s tomb in St Paul’s Cathedral: Reader, if you seek his monument, look around you.

Chris died after a long battle with Parkinson’s Disease. I saw him two days before his death, he was frail but lucid and could remember every chapter heading of a book that he was working on. He was a writer to the end.

In Chris Dodd’s long, prolific and much lauded career, he wrote the obituaries of many of rowing’s departed greats – and now he has joined them. In his own writing, he understood that rowing is shaped as much by those who record it as by those who pull the oars. With Chris’ death, the sport will continue with fewer words worth reading, fewer memories properly kept, and fewer voices capable of explaining why the past matters.

Tim, Wonderful article about Chris Dodd. Fortunately, we have you to carry forth rowing’s heritage.

Regards, John

Many thanks Tim, I have notifies Rowing News, as well as my best friend from school, Vicki Battersby, who knew him too. Small world! Kar

The rowing world has lost a unique talent. When we organised the FISA tour in 2003 Chris wrote an erudite and entertaining description of the route for the handbook which we issued to the particirpants so his words were spread around 95 rowers from 18 countries. I’m sure he wouldn’t mind if I sent it to anyone else who might like to read it. But my favourite memory of Chris was when we were on the FISA tour in Vermont USA and were caught in a hurricane. As we huddled round the,fire back at the YMCA we wrote silly songs and generally had a good laugh at what could have been a disaster. Especially as no alcohol was allowed! RIP Chris, your words will live on even though you are gone.