13 January 2026

By Tim Koch

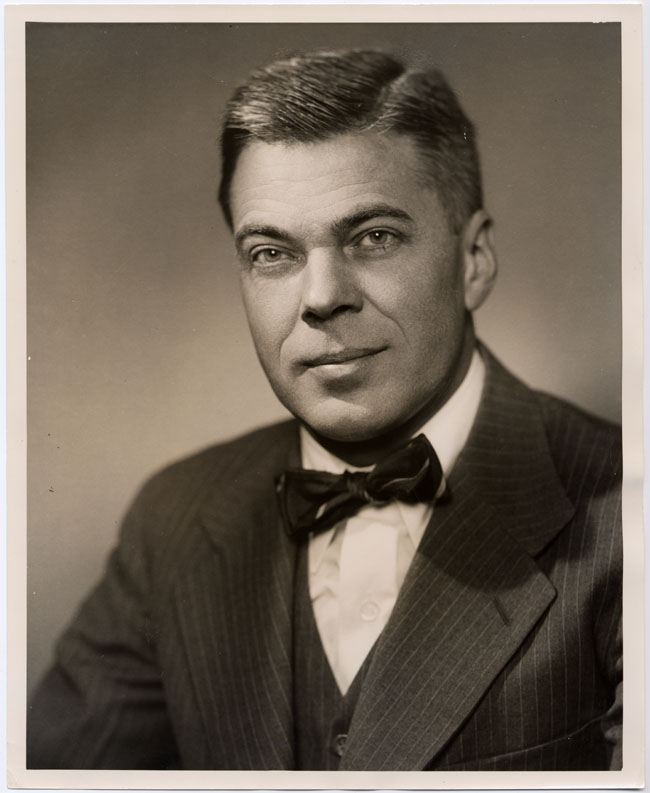

When I recently discovered the above picture of the 1938 CUBC crew, two things struck me. Firstly and unusually, it was not obvious which of the nine was the coxswain. Secondly, pictured just three weeks before the Boat Race, one of the crew was on crutches. I found that this was Thomas “Tommy” Harrison Hunter (1913 – 1997), the cox.

I assumed that Hunter had had some sort of recent accident that did not stop him coxing but necessitated the temporary use of crutches. However, I then found pictures of him on crutches when he steered Cambridge in the previous year, 1937.

Turning to online newspaper archives to find out more, I initially found no reference to any disability or injury that Hunter may have had. Eventually, after looking at two years of very comprehensive reports on the 1937 and 1938 Boat Races, I found just four that referred to Hunter and his use of crutches.

Three of the references were very brief, did not use terms that are acceptable today and were in popular, mass market publications: The Daily Mirror of 1 February 1937 said that “TH Hunter, the new Cambridge cox, is a cripple and walks with the aid of crutches”; The Daily Herald of 1 April 1938 mentioned that he was “a permanent cripple”; Reynold’s Newspaper of 3 April 1938 wrote patronisingly that “a wave of sympathy swept over the crowd as they saw the light blues’ cox… hobble down on crutches. A cripple for life, he handed his crutches to a messenger and scrambled into the boat. Everyone cheered his undaunted spirit.”

The Nottingham Evening Post of 4 September 1937 seems to have been the only paper that provided an explanation of Hunter’s condition:

Mr Hunter must be the only Varsity cox on record who suffered from lameness. He is on crutches as the result of infantile paralysis. An American from Harvard, where he returns a year hence to take up his medical course, he is immensely popular with Cambridge “wet bobs” and also possesses a really fine knowledge of the art and science of rowing. Had he not had his physical disability, he would almost certainly have been a very successful and perhaps notable oarsman…

Infantile paralysis is better known as polio, a feared and contagious viral disease that was once common. It attacks the nervous system, potentially causing paralysis, but is now rare due to vaccines – though there is still no cure. Despite the name “infantile”, the virus also affects adults, famously including President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

As I previously said, it was initially difficult to tell that Hunter was a cox as he seemed as tall and as broad as his rowing crew mates. However, his weight was only 8.5 stone/119 lbs/54 kgs so I assume that his legs were comparatively underdeveloped.

As a child, Hunter attended a prep school with a strong rowing tradition, Belmont Hill, Boston, Massachusetts (Class of ’31). It seems probable that he learned to cox there. He then went to Harvard (Class of ’35) to study psychology and there he steered the Freshman and then Junior Varsity crews. In 1935, he was awarded a scholarship to Trinity Hall, Cambridge, to read medicine and where he coxed for both his college and for CUBC.

The only other British newspaper references that tells us anything about Hunter is a London Evening News piece on the 1937 Cambridge May Bumps that said, Trinity Hall supporters can be sure that if there is a chance of a bump, Hunter will take it, and a March 1938 report that noted that the “majority” of the Oxford Crew were non-smokers but that Hunter enjoyed a cigarette when he came off the river. At Henley in 1938, he steered Trinity Hall in the Grand, but they lost the final to London Rowing Club.

A January 1938 picture of Hunter about to cox Cambridge on the Cam with his crutches cast aside is on the Alamy website. He is also featured in two “Meet the Cambridge Crew” newsreel films, one for 1937 and one for 1938, both now on YouTube.

As I previously noted, the three “cripple” references that I found were from popularist newspapers and I speculate that at the time more genteel publications may have thought it “distasteful” to mention any physical disability.

In 2012, I wrote about Jack Dearlove, a very successful Thames RC cox of the 1930s and 1940s who had one leg amputated as a child and who used crutches thereafter. In 1948, he was chosen to cox the British Olympic eight but the authorities felt that it would not be “right” for a man with a disability to take part in the parade of athletes at the official opening of the Games by the King in Wembley Stadium. He stoically had to watch from the stands with the other 85,000 spectators so as not to “cause embarrassment.”

Tommy Hunter was perhaps the first and possibly the only person with a significant disability to take part in the Boat Race. However, his post-Boat Race career was even more notable.

On his death, Hunter merited many obituaries, notably in the New York Times (account needed) and in the journal of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. The latter began:

Dr. Thomas H. Hunter, a widely respected physician and medical educator… died at the age of 84 in Charlottesville, Virginia on October 23, 1997.

In the course of his long and productive career, Tommy made important contributions as a teacher, clinician, investigator, and academic administrator…

At age six, he developed paralytic poliomyelitis, which affected both of his legs, and he walked with the aid of braces and crutches from then on…

After completing his elementary and secondary education, he was admitted to Harvard College where he compiled an outstanding academic record…

Tommy also won a major letter as coxswain of the Harvard varsity crew. As was true throughout his life, he never allowed his physical disability to inhibit him from enjoying an active life…

(In 1935 his) outstanding undergraduate record won him a two-year Henry Fellowship at the University of Cambridge, where he began the study of medicine.

Despite the time demands of the medical curriculum, Hunter coxed the Trinity Hall crew, and in the second and presumably the last year of his fellowship, the Master of Trinity Hall, Dr. H. R. Dean, professor of pathology at Cambridge, invited him to stay on for a third year. The common wisdom of the time was that Dean, an ardent rowing enthusiast, was reluctant to lose such an effective coxswain!

Hunter returned to Boston in 1938 and completed the last two years of medicine, receiving his M.D. in 1940…

A biography on the University of Virginia’s (UVA) archives website states:

During his internship and residency training at Columbia University Presbyterian Hospital in New York, Hunter began the clinical research that would lead to a dual antibiotic treatment for bacterial endocarditis, an infection of the heart’s lining and valves that had previously been uniformly fatal…

During his following career, Hunter worked and taught in Columbia, Egypt, Venezuela, Tunisia, Kenya, Cameroon, Chile and Brazil.

Hunter’s New York Times obituary noted that in his time at UVA:

Dr Hunter brought a largely regional medical school into national prominence… (He) developed university programmes in international medicine with an emphasis on poorer nations. In the 1950s he was a pioneer in linking American medical schools and their counterparts in the developing world…

During Hunter’s time as Dean, he was an opponent of racial segregation at the hospital and was an early supporter of President Kennedy’s policy of providing federal funding for medical care for the aged. He was also a pioneer of the ethics of medical and biological research.

Hunter’s University of Virginia biography concludes:

Thomas H. Hunter was deeply interested in international medicine, arguing that health and medicine provide a uniquely powerful bridge to international understanding…

His life was characterized by the promulgation of scientific excellence combined with human compassion.

During his lifetime, Hunter was the recipient of many honours but the Thomas Harrison Hunter Professorship of International Medicine at the University of Virginia, endowed by his friends, colleagues and former students in 1989 represents a lasting tribute to him.