29 December 2015

By Tim Koch

Tim Koch continues to go through the Beresford Family Albums.

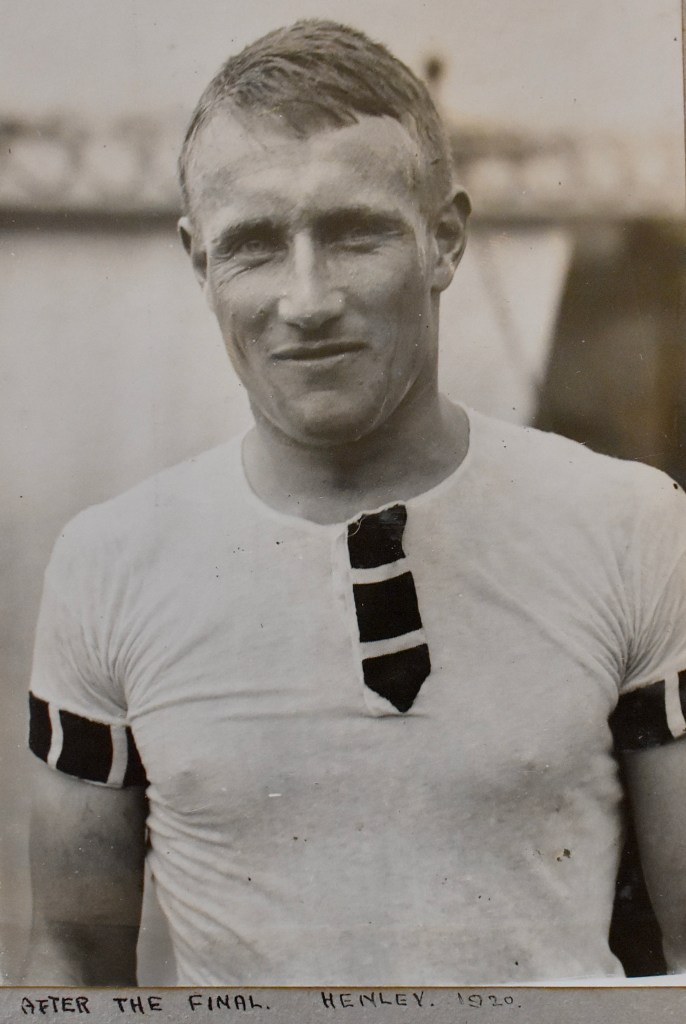

HTBS Types will be well aware of the career of Jack Beresford (1899-1977), a man inevitably called “the greatest oarsman of the pre-Redgrave era” and someone who we have frequently written about. Beresford was a renowned figure in both British and International rowing between 1919 and 1939, a career very neatly bookended by the First and Second World Wars and one really only ended by the latter.

Jack’s son, John, recently gave me access to his father’s photograph albums and I have subsequently produced pieces on his win in the 1936 Berlin Olympics and on his coaching of the English eight for the 1938 Empire Games. The above image of the three scullers is my favourite of the photographs that I found in Jack’s albums.

I now plan three more articles inspired by Jack’s pictures: this one covering his racing career between 1919 and 1922; a second doing the same for 1923 to 1939; and finally, a piece mostly looking at some of his off the water activities, 1917 to 1970.

While I will be providing some chronology for context, this will not be a comprehensive biography, it is more the provision of long and short footnotes for those parts of Jack’s career that he documented in pictures.

As those who recall my 2019 review of John Beresford’s book, Jack Beresford: An Olympian at War, will know, the schoolboy Jack was an outstanding all-round sportsman at Bedford School but one whose first love was rugby. However, any hope of a rugger career for the player nicknamed “The Tank” was ended when Second Lieutenant Beresford of the King’s Liverpool Scottish was shot in the leg in France in 1918.

He went to Fowey in Cornwall to recuperate and here he borrowed a dinghy and rebuilt his strength by rowing it in the estuary and along the coast. By the summer of the first year of peace, 1919, the domestic rowing programme had returned and Jack decided to compete.

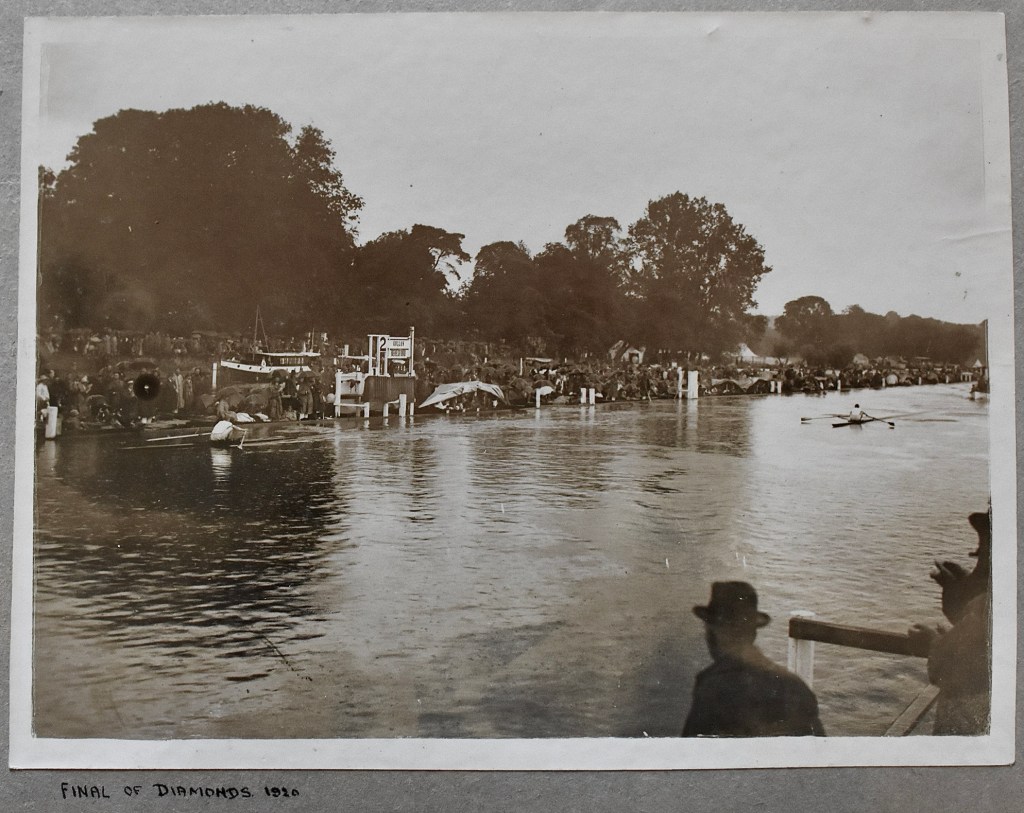

1919 – Upriver Regattas

1920 – Aiming High

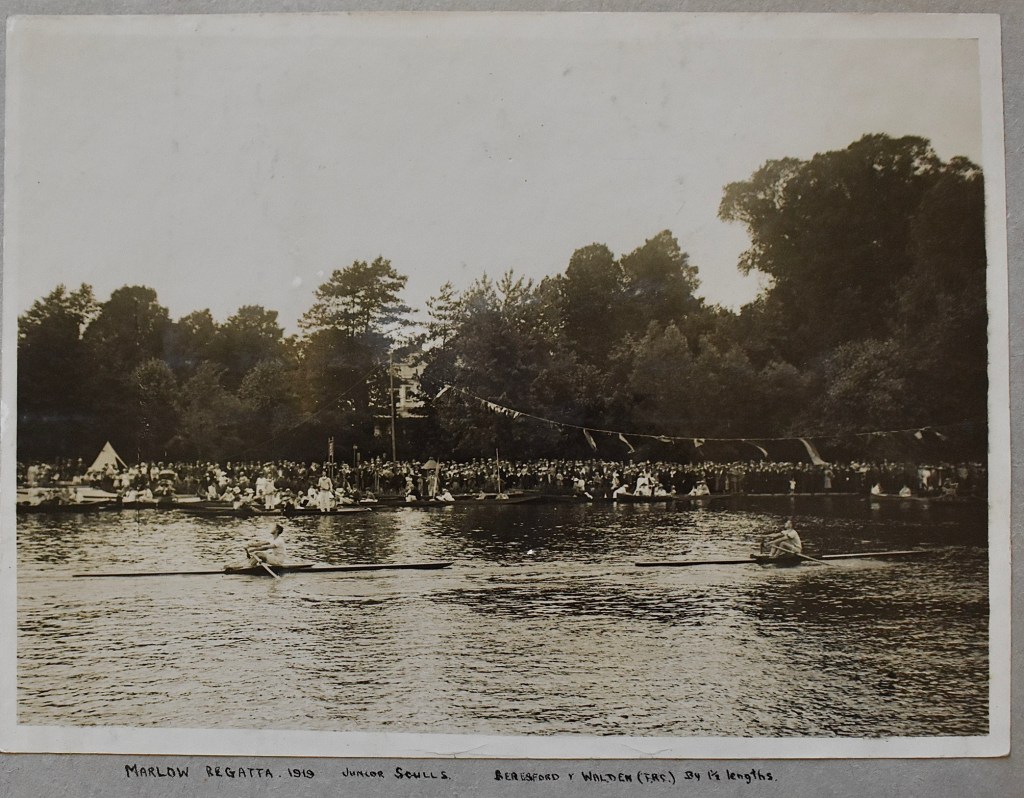

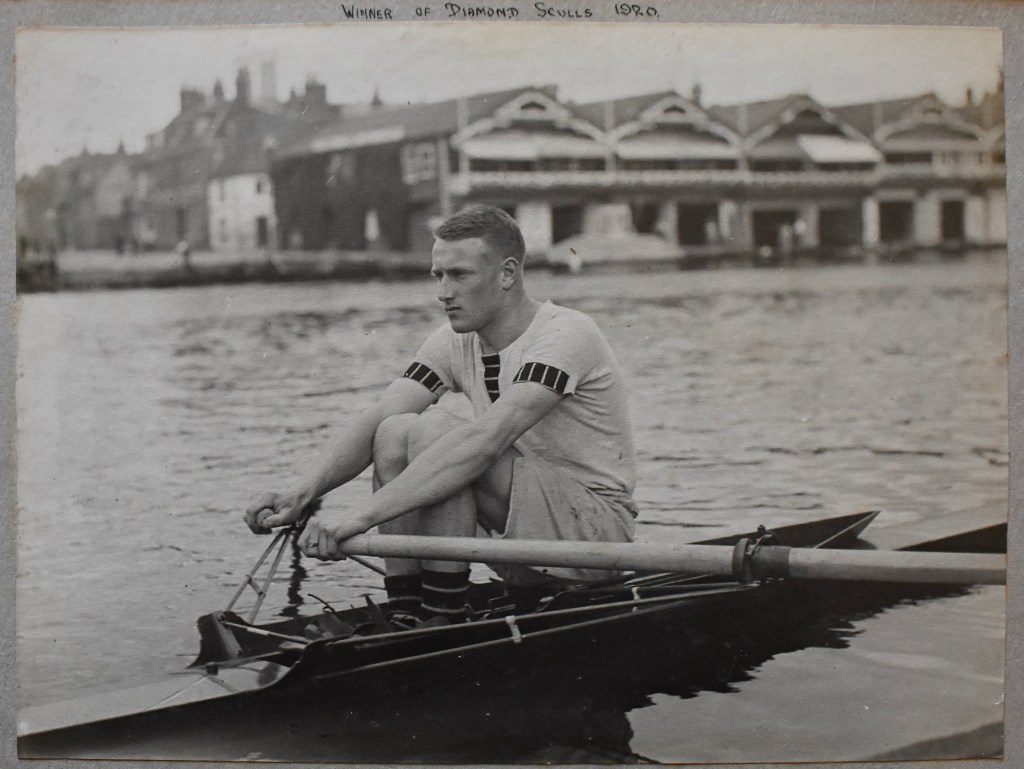

Henley’s Diamond Sculls

In his second race, Jack beat TM Nussey, “easily” meaning that the final would be against Donald Gollan. It would be the start of a rivalry that would last many years.

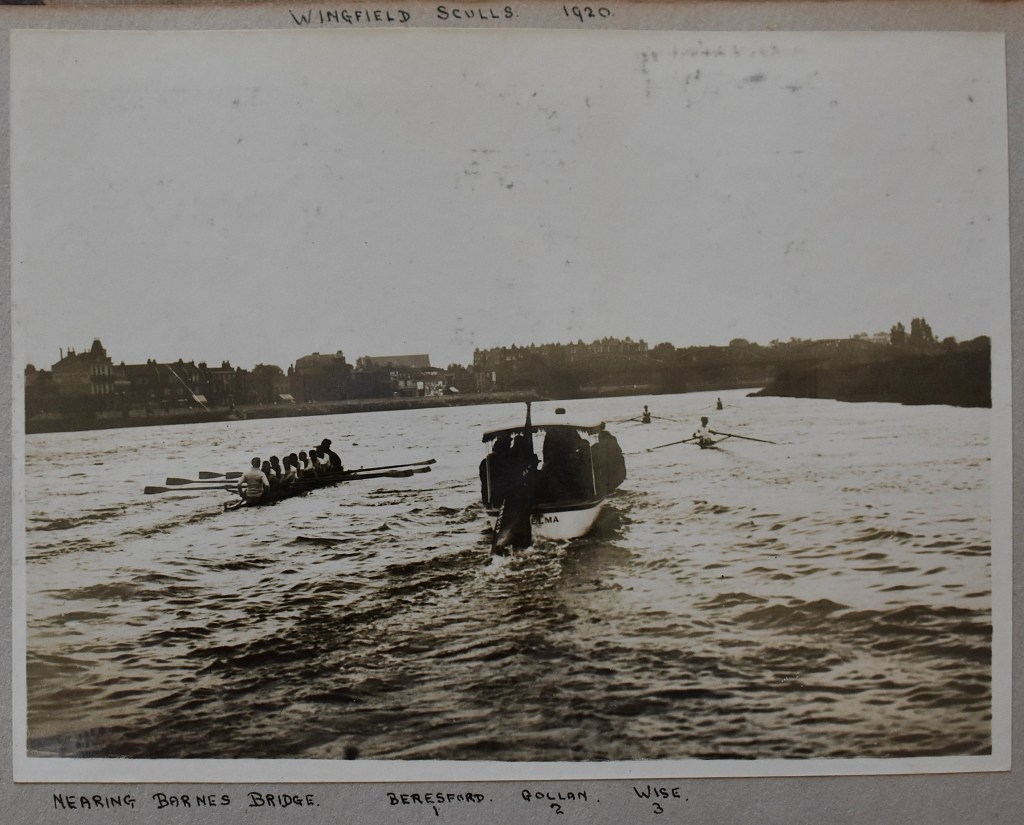

The Wingfield Sculls

Five days before his Wingfields win, Jack had won the London Cup, the elite scullers’ race at the Metropolitan Regatta. These two, together with his Diamond’s win, gave him the “Triple Crown” of British amateur sculling and he was the obvious choice to be the British representative in the single sculls at the upcoming Antwerp Olympics.

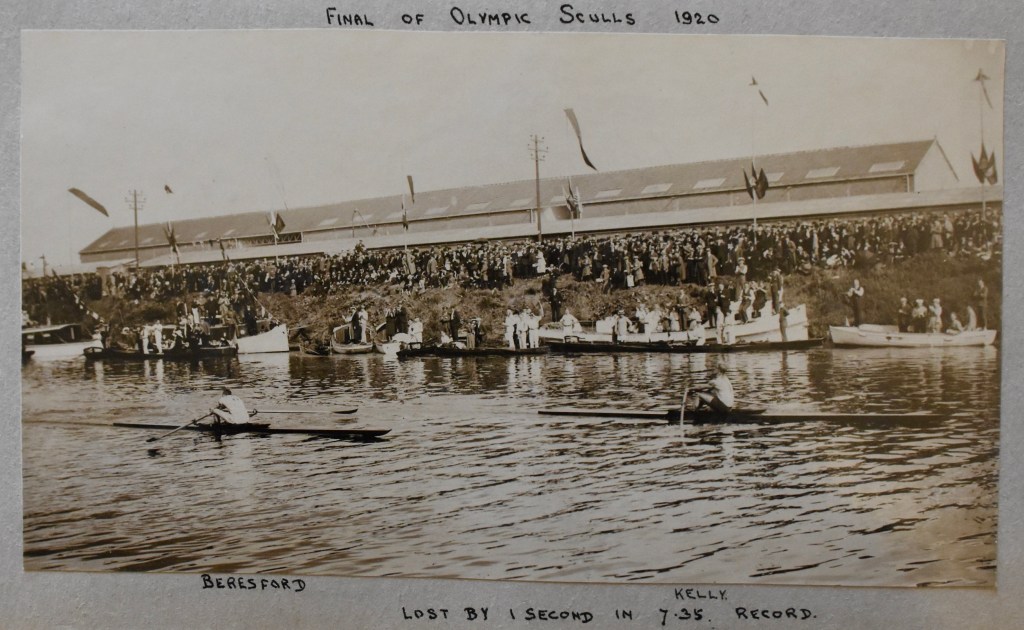

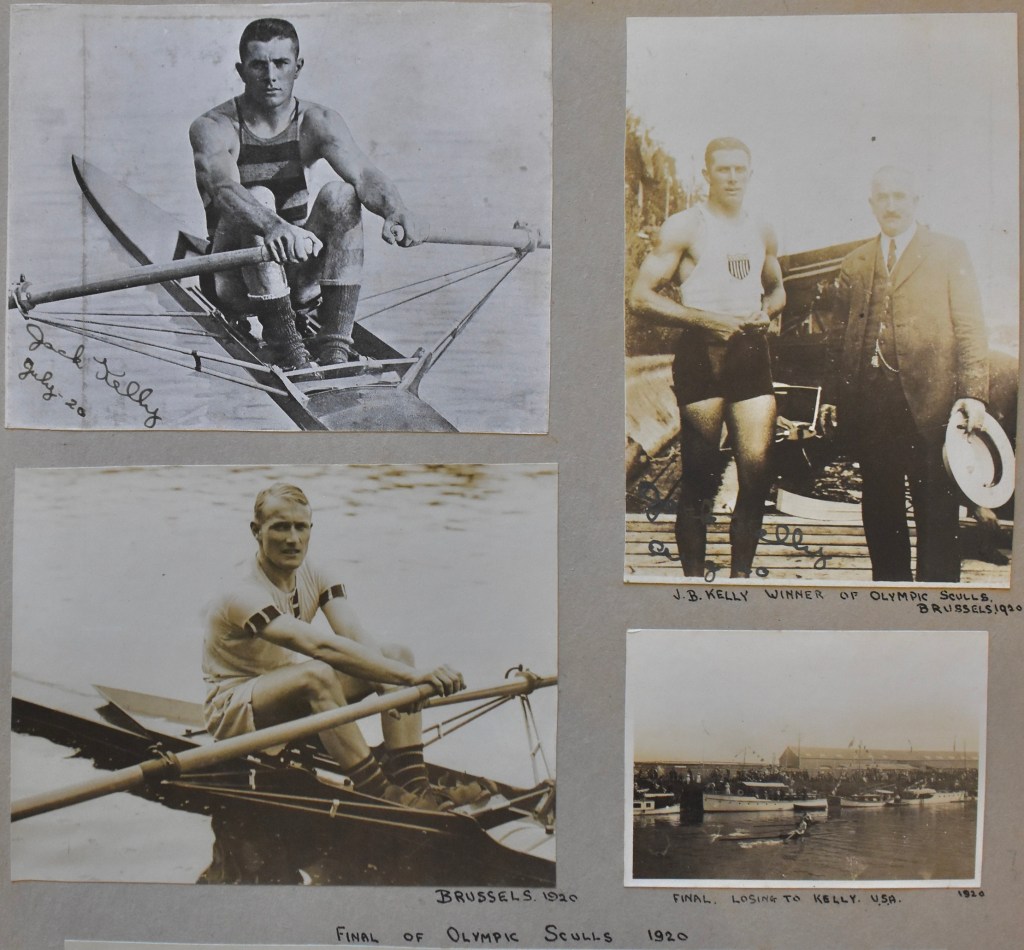

Olympic Sculls

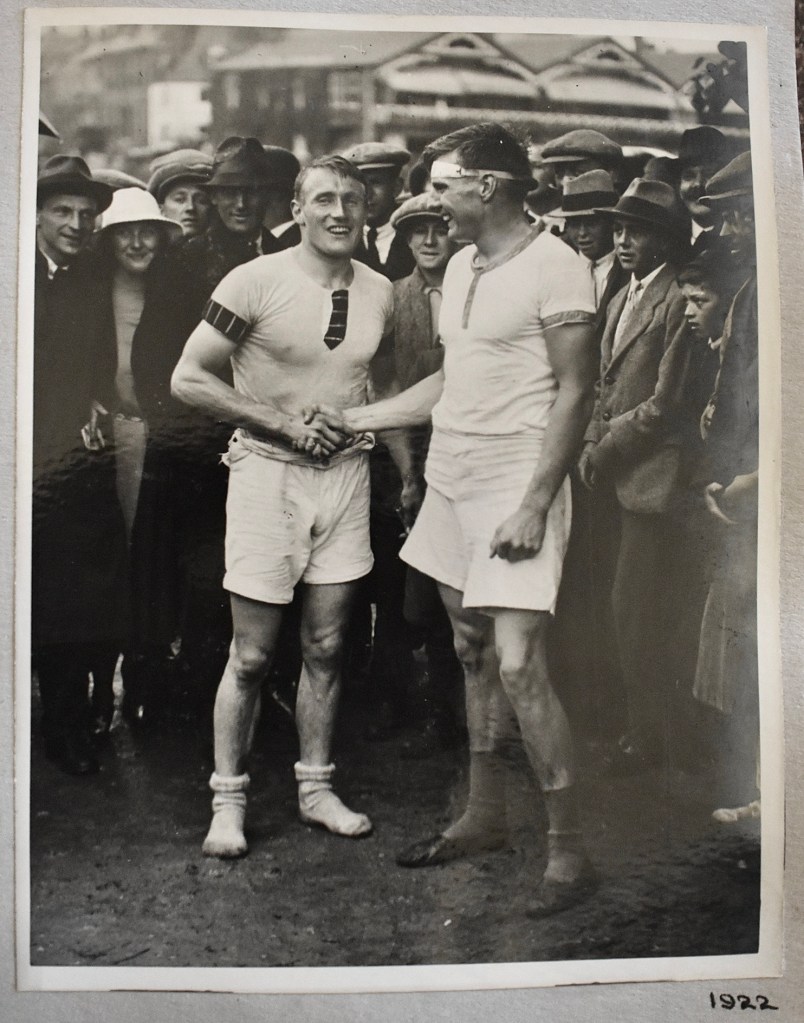

Beresford led most of the way but Kelly passed him in the final strokes. This race held particular significance for Kelly who allegedly had only decided to enter after being excluded from the 1920 Diamond Sculls for reasons that are still disputed. Kelly was reported as saying that he wanted “to get a crack at the man who wins the Diamond Sculls” – which turned out to be Beresford. Despite this, the two men became lifelong friends.

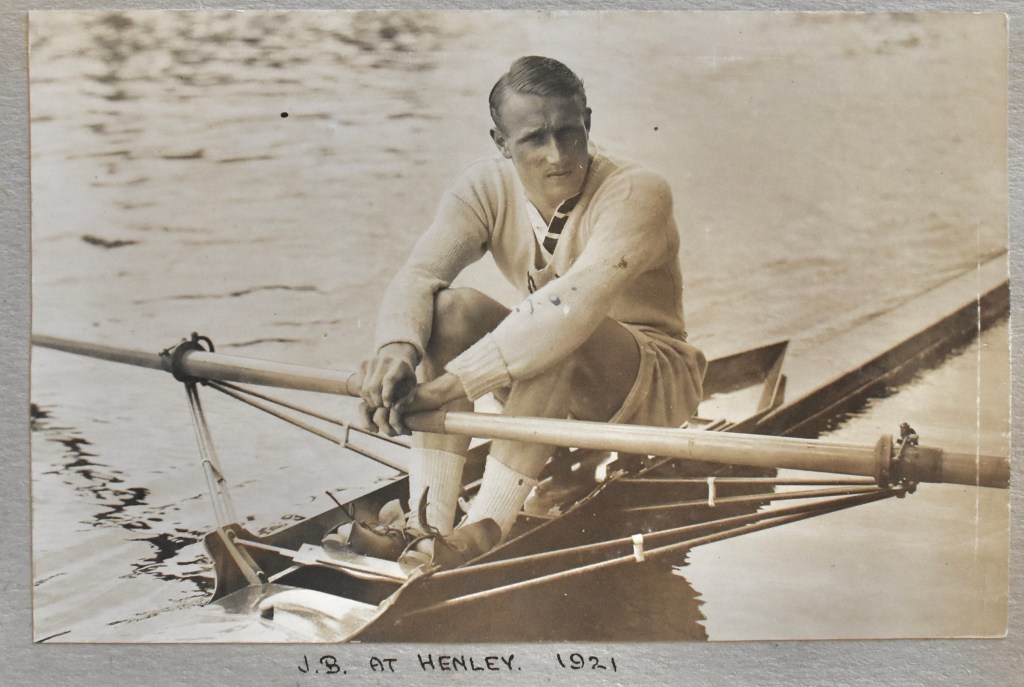

1921 and 1922 – Defeats in the Diamonds

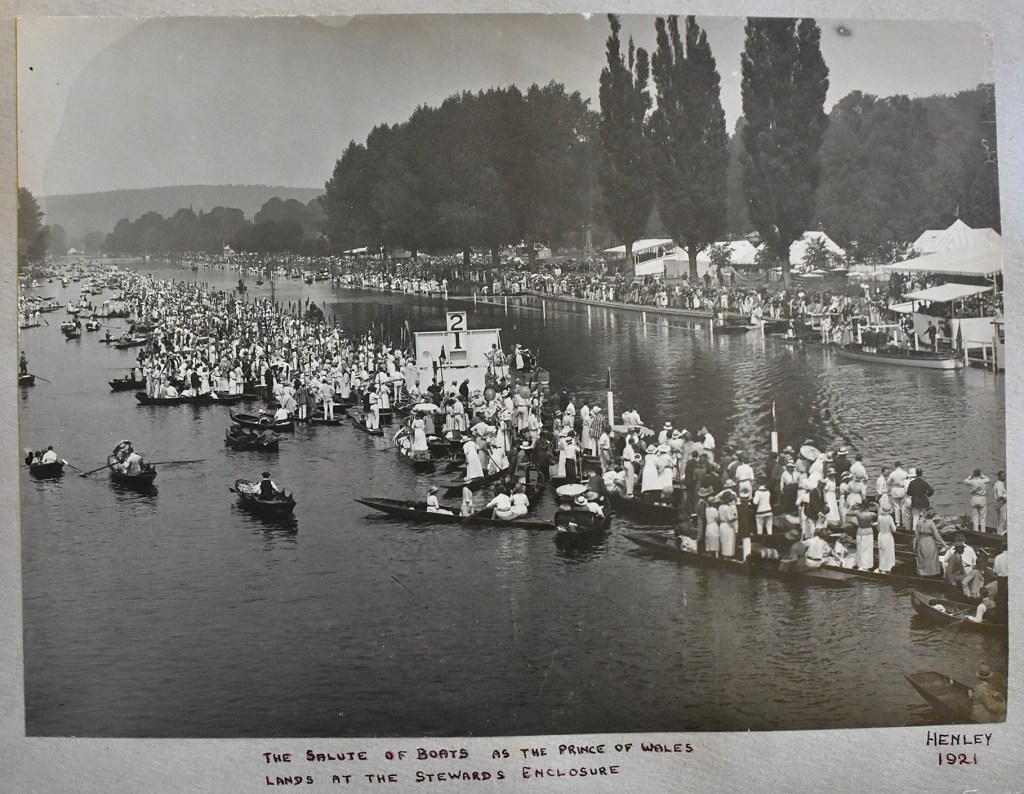

In 1921, Henley was filmed in colour for the first time.

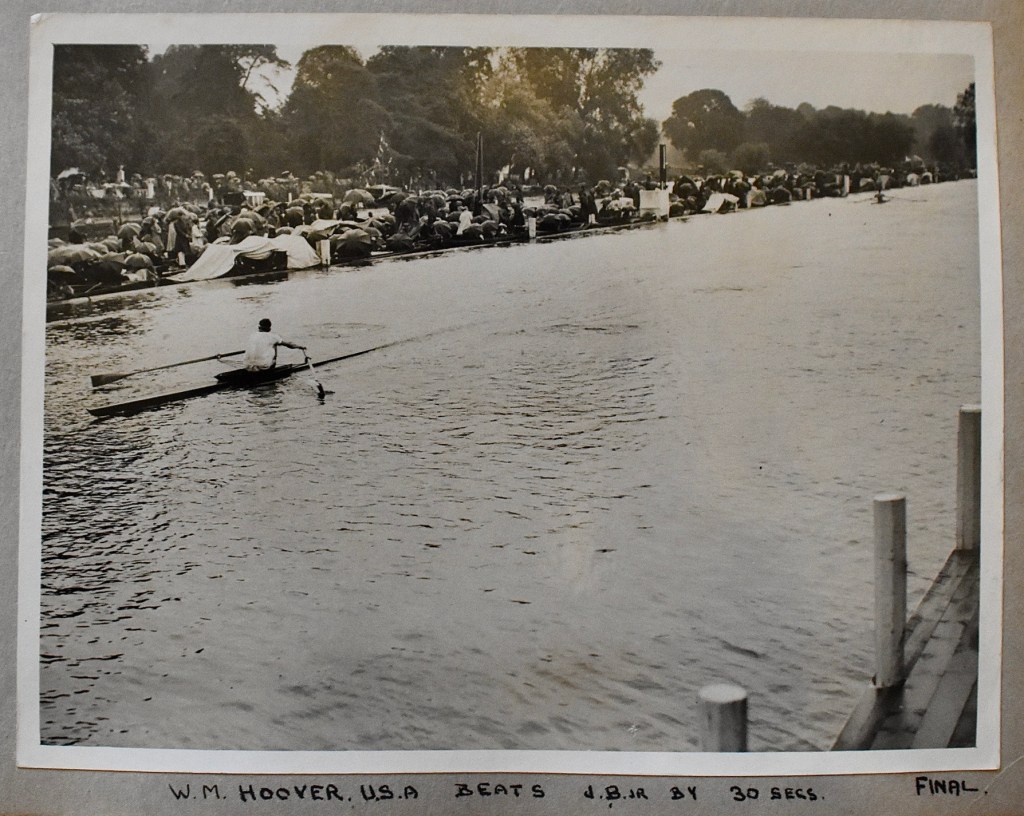

The final of the 1922 Diamonds was between Jack and Walter Hoover of Duluth, Minnesota, USA. At the 1921 US National Rowing Championships, Hoover had caught the attention of the rowing world by winning the intermediate single, the senior single, and the quarter-mile dash. In 1922, he won the Philadelphia Gold Cup in record time.

While the Americans claimed that the Gold Cup was effectively the sculling world championship, Henley held that the race for the Diamond Sculls was the pinnacle of amateur sculling. As if to settle the matter, Hoover sailed to England the day after his race in Philadelphia to compete for the Diamonds, taking the sculling boat that he had designed himself. At Henley, Hoover easily won his two heats, including a victory over AA Baynes, the undefeated Australian sculling champion. In the final, he beat Jack by nearly 30 seconds. The Times wrote:

The race proved one of the greatest sensations that we have had at Henley for a long time, and the pace that Hoover got on his boat in the stiff head wind was a revelation.

While Jack lost in the finals of both the 1921 and 1922 Diamonds, the first was due to an act of sportsmanship on his part and the second was a defeat by a truly remarkable sculler who was on top form.

Part II, Winning Ways, will cover 1923 to 1939.

I had the honor of sharing the Leander dock with Jack Beresford during the luncheon interval at Henley during 1971. After our Kent School eight had been defeated in the first round of the Princess Elizabeth Cup. Our coach coach Hart Perry (later the first American Steward of the Regatta) arranged for my pair partner, Murray Beach and I to borrow a pair from Leander as we were then starting to train for the US Junior coxless pair trials.

As we were about to push off, Hart motioned to the single sculler behind us at the dock, “That is Jack Beresford,” he said simply. Hart had spoken of him often in the past.

Beresford sculled smartly away from the dock, then still a picture of form and strength. He was then 72 years old. Ed Woodhouse Virginia, USA