23 June 2025

By Tim Koch

Tim Koch finds that holding 4th June on 14th June is the least eccentric thing about Eton’s big day.

It initially costs £65,000 to imprison someone in the UK once the expense of police, courts and all the other steps necessary for a conviction are taken into account. For about the same amount, you could send a boy to Eton for a year.

It is true that there are people who have spent time in both places but only one of these two institutions can claim to have invented rowing as an amateur sport, owns its own Olympic rowing course and has a most peculiar way of showing off its rowing crews once a year in the so-called Procession of Boats.

I have previously written:

Eton College is the most famous school in Britain and, possibly, the world. Sited just over the river from Windsor, it takes boys aged 13 to 18. Founded in 1440 by Henry VI to provide free education to seventy poor boys who would then go on to King’s College, Cambridge, and eventually become civil servants, it has produced nineteen British Prime Ministers and, more importantly, innumerable oarsmen.

There are two notable dates for Eton boys and their families during the year. There is St Andrew’s Day (30 November), for which the main attraction is the impenetrable “Wall Game’’, and the so-called “Fourth of June” (which is rarely held on 4 June). This is the birthday of Eton’s greatest patron, King George III (1738-1820), and is the school’s equivalent of parents’ day or open day.

The entertainments on The Fourth include a wide range of exhibitions, a promenade concert, a performance of speeches, a cricket match against Old Etonians, and most famously, The Procession of Boats.

The Procession is a “row past” by most of the school’s boat club in front of the parents and the teachers assembled in one of the school fields that rolls down to a backwater of the Thames. It starts with the most senior boys’ boats and ends with those of the youngest. This does not sound particularly special – but there are several “Etonian twists.”

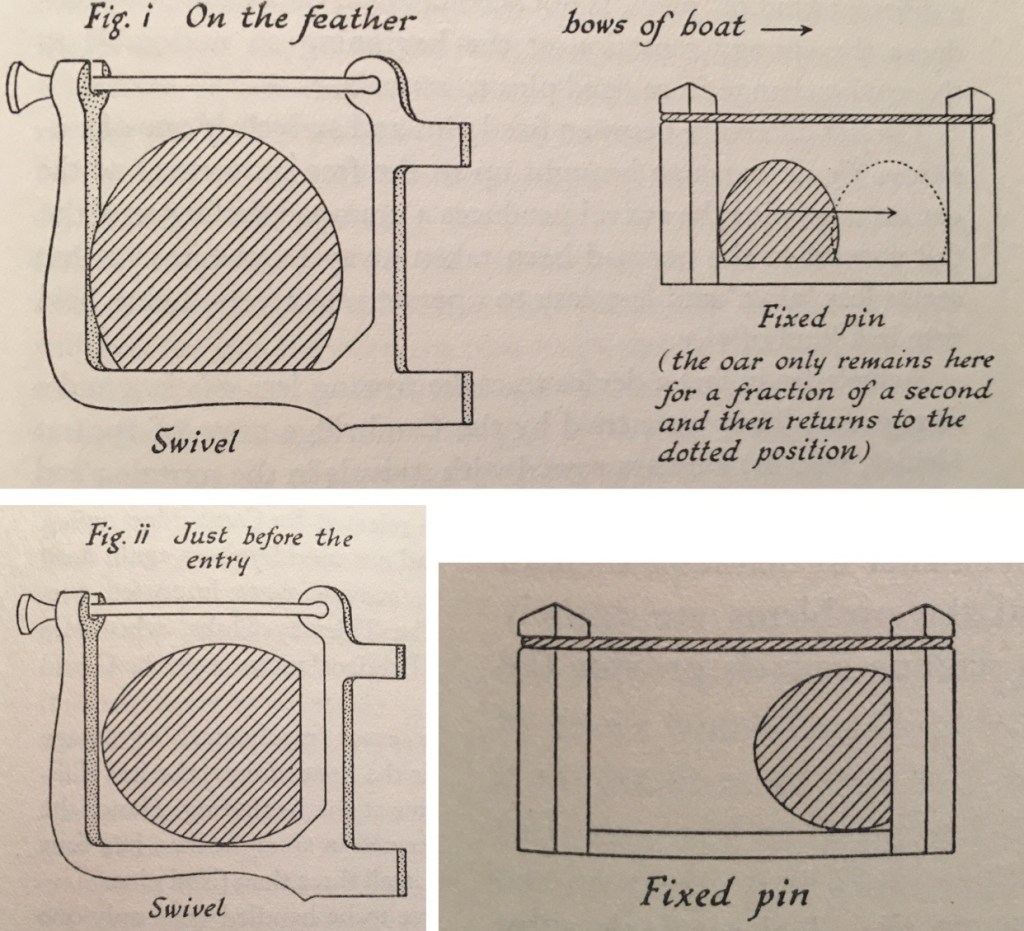

The ten wooden boats involved are fixed seat and most have fixed pin (as opposed to swivel) rowlocks. The blades have “needle” spoons and the leading boat is a ten-oar.

All the rowers are dressed in the uniform of eighteenth-century midshipmen, with the cox dressed as a captain or other senior naval officer from Britain’s naval past. Most strikingly, the oarsmen wear straw boaters that have been extravagantly decorated with fresh flowers by their house matrons or “Dames.”

At a certain point in the row past, each boat in turn stops and the entire crew and the cox stand up. Those in boats with open fixed pin gates hold their oars erect and stand up in pairs. Those in boats with closed swivel rowlocks leave their oars on the water but all stand together.

While Victorian style eights are a little more stable than are modern racing boats, standing is still a difficult thing to do. The standing crew then faces Windsor Castle, remove their hats and cheer the current Monarch, the school, and the memory of George III, shaking the flowers from their boaters into the water. They then resume their seats and row away.

At Masters’ Boathouse

Eton has three or four boathouses that I know of, but Masters’ Boathouse is where the ten “Procession” boats, only used once a year, are kept. The boats are put on the water 48 hours before they are used so that the wood of the older craft can expand and hopefully become a little more water tight.

Tomorrow: Part II of III, The Upper Boats.

I went to a very humble school 280 miles north of Eton but learnt to cox at LMBC, and actually did a bit of coaching and coxing at the Eton Excelsior town club after I started working for Mars Confectionery, just 2 miles up the road in beautiful, scenic Slough. I know Windsor and Eton well – however, I did not know much at all about the events you write about here, and I found the article fascinating. I look forward to subsequent instalments – thank you.

What a fascinating glimpse into one of Britain’s most tradition-rich institutions! The juxtaposition of heritage, eccentricity, and athletic seriousness at Eton never ceases to intrigue. I love how this post blends historical context with sharp wit—especially that comparison between the cost of incarceration and Eton tuition! The description of the Procession of Boats makes it sound like a delightful, if quirky, spectacle. Looking forward to reading Part II and seeing more of how these traditions unfold on the river.