27 January 2025

By Peter Williams

Peter Williams tells the story of an 1885 poorly prepared crossing of the English Channel by W. H. Grenfell, Lord Desborough.

The many exploits of William Grenfell described in the biography which I co-authored with Sandy Nairne (Titan of the Thames: The Life of Lord Desborough, Unbound 2024) included the occasion in 1885 when, as the former MP for Salisbury, he stroked an ill-prepared Oxford crew in an unsuitable clinker eight across the English Channel. New research provides the opportunity to share more about this intriguing story.

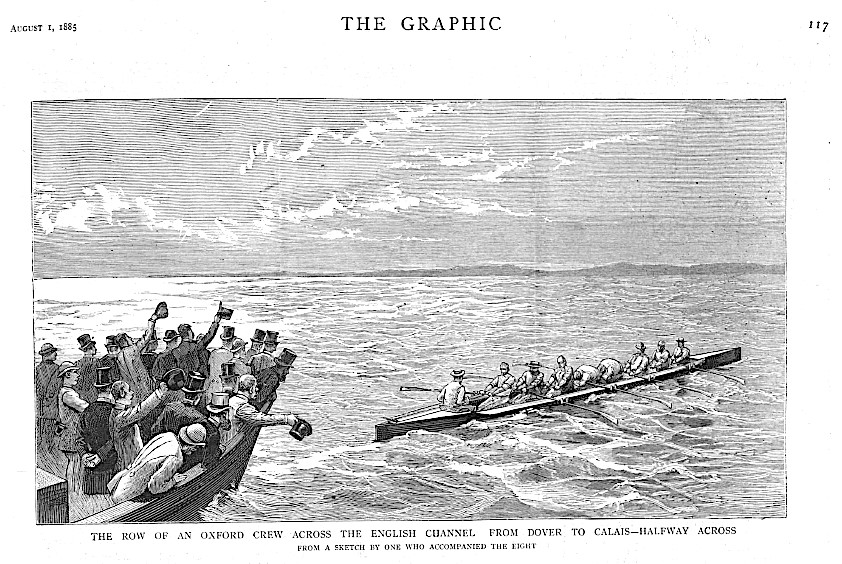

The row from Dover to Calais took place on 25 July 1885 and is captured in a lithograph published in The Graphic newspaper on the following weekend, on 1 August. As can be seen above, two members of the crew were in considerable difficulty!

Exactly why Grenfell and the rest of the crew decided to make the journey is not clear. Grenfell had been elected as MP for Salisbury in 1880 but in 1882 was appointed as Parliamentary Groom in Waiting. By convention, this meant he should resign as an MP and face a by-election (though by custom this was normally unopposed). However, another candidate stood against him, and he was defeated. He didn’t return to Parliament until November 1885.

One suggestion was that he remained angry about this defeat and took on the challenge of the Channel – although a couple of years later – as an outlet for his frustration. Equally, it might have been because he was simply looking for new challenges. He had recently spent a few weeks in the Sudan as a correspondent for the Daily Telegraph, reporting on the conflict with the Mahdi, and was otherwise wooing Miss Ettie Fane whom he later married.

Whatever the motivation, he assembled a scratch crew of mainly former Oxford oarsmen some of whom had not rowed for some time and, with very little training, the crew certainly left a lot to be desired. The crew members (listed in the end notes) included H. Blagrove, an Oxford waterman, H. M. Leigh, cox, from Dover Rowing Club and E. F. Slocock, from Jesus College, Cambridge, at bow, joining perhaps because his brother A. E. Slocock from Merton College was included.[1]

The Prelude

The crew assembled in Dover the week before and the boat, described as an Oxford Torpid and used for practice on the Tideway, was launched into the Harbour on 18 July in order to allow the crew to prepare. It was a six-year-old craft from Salters, 28 inches wide amidships, 17.5 inches towards the bow and 26 inches at the stern, weighing between 70 and 80 lbs. When fully loaded there were just eight inches of freeboard. Only two of the chosen crew were there for the launch, and for a one-hour practice row Dover Rowing Club members helped out. Even though rowing in the lee of the pier the swell was such that the boat rolled and one oarsman snapped his oar. Given the length of the boat and the underlying swell at times, the boat wouldn’t rise over the waves and it was going to be hard to get a full eight-oared shove.

Testing its capabilities in Dover Bay, it was evident the boat settled very low and heavy in the water and it was ‘declared by many that it would only under the most favourable circumstances succeed in crossing’.[2] The ends of the boat were covered in canvas and. 6 inch splashboards were fitted but these were laid horizontally, as can be seen in the image and apparently lined (presumably underneath) with cork. Each man was equipped with a large sponge to ‘remove any water which may be shipped’ and Grenfell subsequently added to the sponges by buying eight jam jars for use as bailers.[3] Finally, it was noted that – of potential necessity – all the crew were accomplished swimmers.

On the following Monday a further five members of the crew arrived and further practice took place. This didn’t initially include Grenfell though we must assume he was there at some point. Conditions in the Channel were not favourable for much of the week, and they were close to abandoning the attempt when, on the subsequent Friday night, conditions improved. But by then Grenfell’s social diary had taken over.

Grenfell reflected on the conditions: ‘Of course there’s no difficulty in getting across the Channel in a broad beamed boat, but you want an uncommonly calm day to take a sixty-foot long, sliding seat, out-rigged clinker-built eight to the French shore’.[4]

It was arranged that a harbour tug would accompany them and initially the thought was to aim straight across the Channel towards either Cape Gris-Nez or Calais though some advised them to focus on Boulogne where they might benefit from an ebb tide for much of the crossing.

On the Saturday – 25 July – conditions were suitable but the start was delayed because Grenfell was still on his way back to Dover. He had spent the previous evening at a ball in London and by his own admission had neither any sleep nor breakfast. He arrived at 10am and the crew pushed off almost immediately, at 10.10am.

The Crossing

The flood tide having two more hours to run and with a strong current around the pier some water was shipped immediately as the stream caught the boat. But they pulled through it and once beyond the pier settled into a steady rate of 28 strokes per minute (and ranged between that and upwards towards 40 throughout the crossing). After twenty minutes the eight was in more ‘lumpy’ water, and with a light breeze, a little more water was shipped. Good progress was then made until H. H. Kelly at 4 got his oar stuck in his rigger which delayed them, and again more water was shipped, necessitating more bailing. Indeed, Grenfell commented that, ‘our boat would keep filling, and we had to easy over and over again in order to bale her out’.[5]

However, after some 50 minutes, the eight had covered nearly five miles and by 11.15 it was almost eight. Grenfell was apparently attracting some attention from the spectators on the tug for his ‘powerful stroking’. A little later, with nine or ten miles covered and the French coast appearing, the crew faced warmer temperatures as the sun rose higher and there was little breeze. By midday they were at the halfway mark and in calmer water. So they took a brief pause before restarting. However, it seemed that they were heading too far west and so corrected the course to aim for low-lying land near Calais, an adjustment they made again after thirteen miles. This helped to compensate for the ebb tide they would face imminently. The newspaper commentary noted that the crew were ‘pulling the boat along in fine style, rowing a good 30 to the minute’. By 12.30pm Calais was visible just seven miles away and the cox was able to keep the boat’s bow headed towards the Calais piers.

Yet, even with the end in sight, it became evident that H. H. Kelly at 4 and L. Player Fedden at 5 were struggling with fatigue – indeed the latter’s ability to row had caused concern on the tug throughout the crossing and at 12.45 the boat came to a halt with Grenfell reporting that ‘both were done up’. The crew restarted after a break, but Player Fedden continued to rest while Kelly could only manage a ‘weak stroke’. A tender came over from the tug – the two men being described as ‘completely fagged out’ – and both were advised to retire, but neither would leave the eight: Player Fedden lying prostrate in the bottom of the boat and Kelly complaining of dizzy spells and unable to speak!

The remaining six oarsman resumed rowing ‘with a good stroke from Grenfell’ and put on a spurt, with Kelly and Player Fedden trying to join in before collapsing ‘like dead men’. By 1.30pm the eight faced more swell and the bowman, ‘young’ Slocock, was also beginning to struggle. However, the others rowed on with encouragement from Grenfell and cheering from those on the tug. They were nearly swamped by a passing ferry, whose passengers gave a shout which prompted Kelly and Player Fedden to try to resume rowing. After Grenfell insisted they stop – or he would stop the boat – they obeyed his command. By 2pm the eight was about a mile and a half from the French coast and the crew made good progress despite the heat and exhaustion. 4 and 5 remained prostrate but as the boat reached the Calais piers at 2.35pm, they ‘sat up and pulled as well as they could’ across the harbour, enjoying the welcome provided by the French crowd.[6]

On arriving, Player Fedden was well enough to get out of the boat along with the rest of the crew. Kelly took some time to recover but they all went on to be entertained by the Mayor of Calais at the railway buffet.

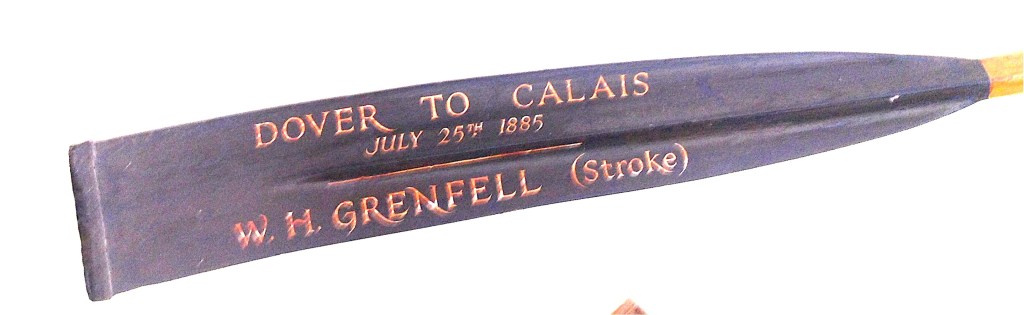

Grenfell’s crew had travelled roughly twenty-seven miles in a time of approximately 4 hours and 20 minutes. And nobody had needed to swim! Without doubt other crews in similar boats have made this crossing and it would be helpful to put this particular crossing in context. However, Grenfell and his crew did well considering the difficulties they faced and for a brief moment in 1885 it drew considerable attention. Grenfell retained the oar he used and had it inscribed. It now hangs in Maidenhead Rowing Club.

[1] Full list of crew names; E. F. Slocock, bow, Jesus College, Cambridge; T. L. Ames, Merton College, Oxford; H. Blagrove, Oxford Waterman; Rev. H. H. Kelly, Queens College, Oxford; L. Player Fedden, Merton College, Oxford; A. E. O. Slocock, Merton College, Oxford; R. W. Tattersall, Exeter College, Oxford; W. H. Grenfell, stroke, Balliol College, Oxford and cox, H. Leigh, Dover Rowing Club.

[2] Quote from Isle of Wight County Press, 1 August 1885, page 6

[3] Quote from Banfield, F, W. H. Grenfell of Taplow Court, Cassell’s Family Magazine, 1896, page 767

[4] Quote ibid

[5] Quote ibid

[6] Quote from Isle of Wight County Press, as above

An unsuccessful and even more unwise attempt to cross the Channel in an unsuitable racing boat is recorded in my biography of Thames RC sculler and eccentric, St George Ashe:

Early evidence of strange and unwise behaviour by Ashe occurred in September 1898 when he twice tried to cross the English Channel to France in an ordinary Thames sculling boat, thin shelled and weighing just 25 pounds. In his first attempt, the hull cracked after three miles and the boat filled with water. A week later during a second try, a wave caught him and broke the scull in half. No one was impressed by the effort or surprised by the result and the Sporting Life of 19 September called it ‘by common consent, foolhardy in the extreme’. It added, ‘There are various degrees of British pluck, some the outcome of misdirected enthusiasm. (Ashe’s attempt) was a case in point’.

I have an illuminated oar from that crossing with all the crew names on it .