10 December 2024

By William O’Chee

Winning a Blue is unquestionably the pinnacle of Oxford sporting achievement, but how would you feel about an Oxford Red or even an Oxford Yellow? What on Earth is that, one might ask? The explanation is certainly a tale worth telling.

Oxford’s adoption of dark blue as its sporting colour originated in 1829, when an Oxford crew, stroked by Thomas Staniforth of Christ Church, raced a Cambridge crew, stroked by W. Snow of Lady Margaret Boat Club.

Tradition tells us the Oxford crew wore dark blue, as five members of the boat were from the House, and they appropriated its colours. Their opponents rowed in a boat built by Thomas Searle of Westminster and painted pink, with the crew sporting white shirts piped in pink ribbon. (As there were no Westminster men in the crew, the choice of pink for the boat could not have resulted from any association with the school, and may have been the choice of the boatbuilder.) It was only subsequently that Cambridge adopted their current minty green, which has curiously become known as Cambridge Blue, and which good taste might consider a poor choice.

Although the first cricket match between Oxford and Cambridge was in 1827 and is sometimes termed the “Blues cricket match” it is properly the University Match. In fact, the Oxford cricket team did not wear blue until 35 years later. This little-known fact is provided by W.B. Woodgate, a legendary Oxford oarsman, and somewhat sniffy raconteur. In his work, Reminiscences of an Old Sportsman, he wrote:

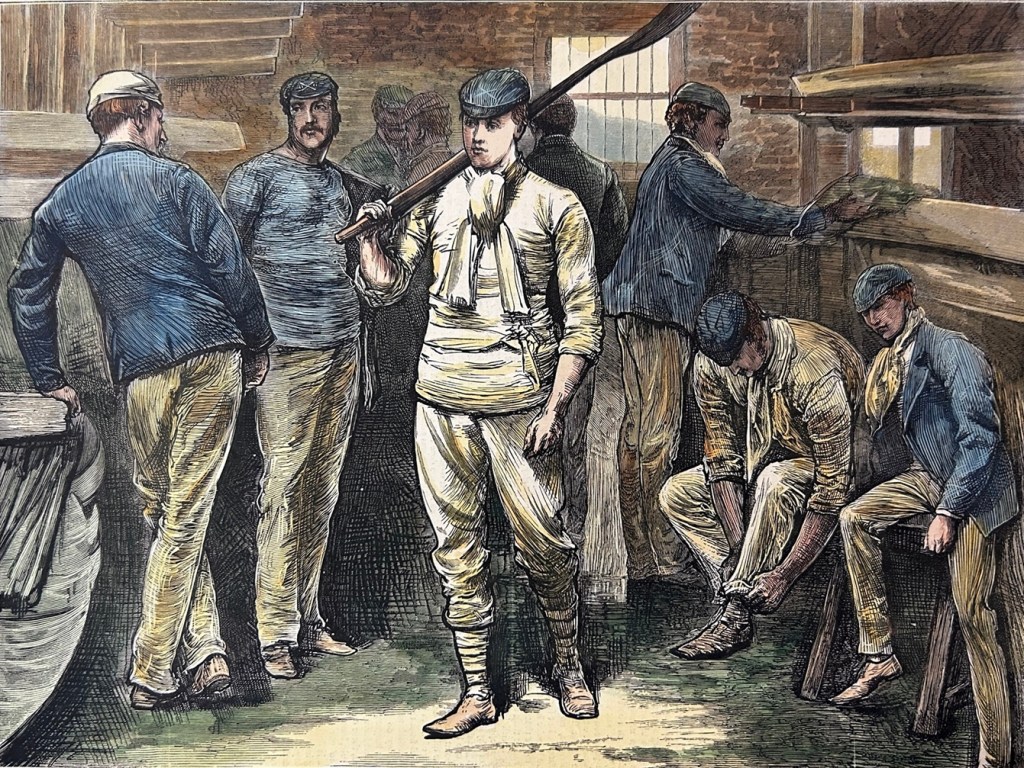

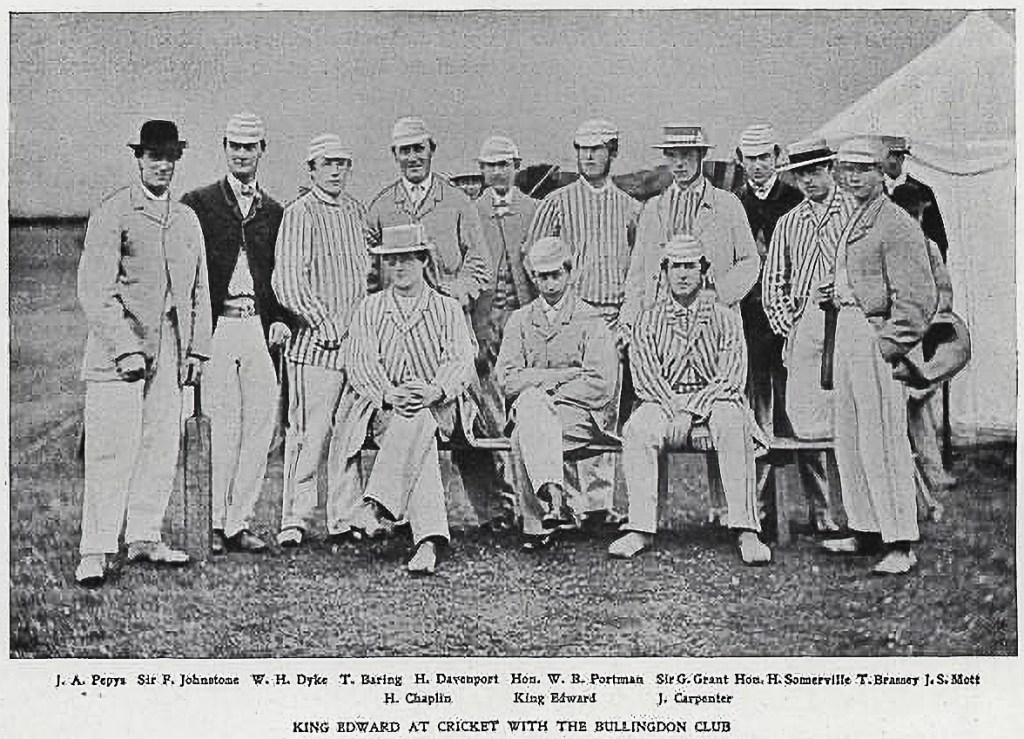

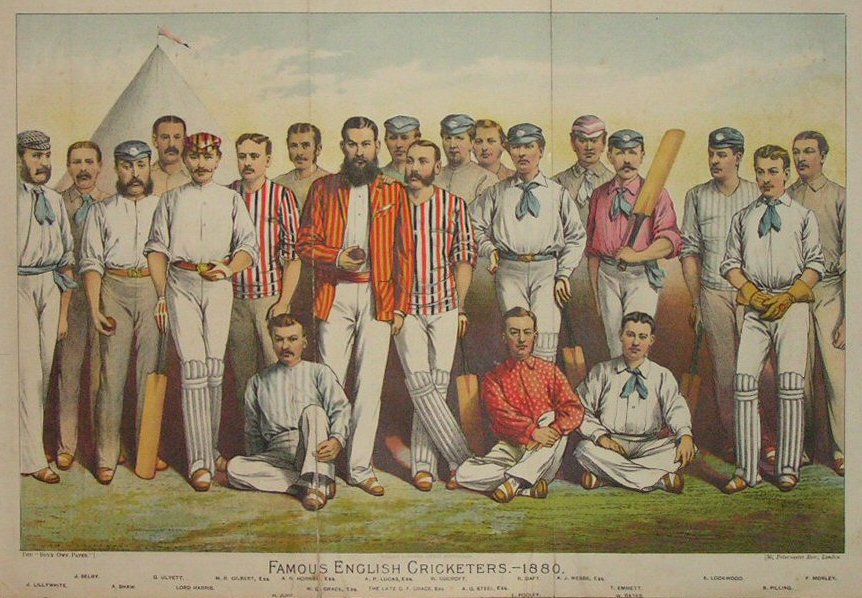

In the Whitsun term of the Preceding year, 1862, the University Cricket Club approached the University Boat Club for leave to wear dark blue at Lord’s. Till then, broad dark blue ribbon, and blue coats with no crest on them, had been the monopoly of the University eight. Oxford elevens had no specified colour; at Lord’s they had been in the habit of performing in all sorts of shirts and ribbons: here Harlequins; there Free Foresters, Bullingdon or Perambulator. The result was that spectators often were puzzled, on arrival, to know which side was in the field.

To appreciate what a panoply of colour must have ensued, one must understand that the Harlequins wore shirts of dark blue, maroon and buff, while the Bullingdon were attired in white and light blue striped shirts, with white trousers with two light blue stripes on the side. The Free Foresters wore red, green and white.

Oxford cricketers first adopted uniform white shirts in 1861, and as noted above, sought to adopt dark blue only in 1862. However, Woodgate notes that it was not as simple as that:

…as a matter of sporting etiquette, the authorities of the eleven sent a formal application to us for leave for the adoption. It must be borne in mind that at that time there were no Inter-University athletics; though they were in the air, hatching. Besides the boat race, cricket, rackets, billiards (started in 1859) and Aylesbury steeplechasing were the only passages of friendly arms between the two Almæ Matres; and of the relatively minor sports, none had dreamed of sporting light or dark blue, which were regarded as Boat Club colours exclusively.

It was therefore considered to be in the gift of O.U.B.C. – and specifically the Committee – to determine whether Oxford’s cricketers should wear the same colours. The proposal did not receive enthusiastic support from the Committee, which was composed of W.B. Woodgate (BNC), W.M. Hoare (Exeter), C.R. Carr (Wadham), A.R. Poole (Trinity), and W.B.R. Jacobsen (ChCh). All were members of the 1862 Blue Boat. Hoare and Carr had, as Woodgate records, “enough cricket talent to play, when occasion allowed, for their colleges.” The other three, however, were “pure wet bobs.”

Being protective of their colours, the majority of the O.U.B.C. Committee proposed an alternative, to be considered by both universities for mutual approval. This was:

…that blue, light and dark, should remain as before distinctive of the aquatics, and some other shade of light and dark (e.g. pink and crimson) be allotted to the eleven; leaving for the anticipated future of Inter-University athletics, primrose and orange, and so on.

It followed that other sports might adopt red or even yellow as their colours, in corresponding shades for the two universities.

If this seems to the current reader somewhat extraordinary, the tale of how it did not come to pass is even more extraordinary, and not a little perfidious. We shall let Woodgate take up the story:

The cricketers had meanwhile flattered Hoare, electing him a Harlequin, which was usually a compliment reserved only for such as at least soared to the standard of a University fifteen or sixteen.

When the day for Committee arrived, one of our three wet bob dissentients had unexpectedly had to be absent, for some family obsequies. I forget whether the absentee was Poole or Jacobson. The effect was, to divide the Committee, two and two for and against. Hoare, as president, claimed a casting vote, and by it the eleven got blue, subject to conditions-one, to wear the ribbon only on variegated straw, not white; and secondly, not to bind their blue coats with blue silk trimming.

So, Oxford cricketers snared their Blue, and athletics followed suit not long after by agreement with the Eight and the Eleven. Woodgate’s worst fears would come true as other University sports “pirated” the colour, but all have brought to the contest the same pride in their university, their team and themselves that Woodgate himself well knew.

The subsequent 162 years have seen many changes to Oxford sport. However appealing the reservation of a Blue for rowing alone, the multitude of current sporting options at the University pose challenges. What colour would be available for the University team in Ultimate Frisbee? Any takers for yellow?

I thought I knew everything about this topic, but you’ve revealed new points.