19 February 2024

By Jonny Cantwell, text and pictures, unless otherwise indicated.

Not much escapes the eagle-eyed of the world’s rowing social media elite. The rumours of a film adaptation of The Boys in the Boat started to circulate in mid-2021, but by December of that year it seemed certain to be happening and the name George Clooney was being attached to these stories. Then in January 2022, gossip began to tell of replica eights being built in London for the filming.

At about the same time as friends forwarded me an article from Hear The Boat Sing, I was tipped off by a local about the goings-on at the boat builder under Richmond Bridge. Boatbuilder Mark Edwards is perhaps best known in the UK for building the Queen’s Jubilee Barge, Gloriana, but he has built many types of boat and has done a few movie jobs over the years. Living nearby and knowing Mark, I quickly headed down to investigate.

On the side of the Thames, Mark’s team were busy finishing off the large training barge used in the film. Hidden away in the Richmond Bridge vaults directly beneath the road, another boat was taking shape. Under the guidance of Bill Colley, one of the few remaining timber racing boat builders, the frame of a timber eight was being readied for its plywood skin.

A love of timber

Many years ago I had the chance to meet Graeme King (an Australian boat builder who made his name building boats for Harvard) when I raced the Head of the Charles. He was kind enough to let me visit his workshop and provided a great many insights into not just timber boat building but also into boat design as a whole. He had allowed a few people to build racing sculls to his plans over the years, but these had all been done using the cedar strip method (very familiar to canoe and kayak makers). His reasoning for this was that working with a thin ply skin was very difficult to do, and almost impossible as a first time builder.

With Graeme’s advice in mind, I asked Mark and Bill if I could come to assist when it was time to put the skins on the eight. The chance to get hands-on experience with these traditional techniques was not one to be missed. Mark said it was up to Bill, and luckily Bill was happy for me to join his small team. Mark pointed out that, “No one is ever going to do this again, so you’d better join in.”

Recreating a legend

The boat was being built as a complete replica of the Pocock built Husky Clipper which was used by the winning 1936 crew featured in the Daniel James Brown’s book. The original boat still exists and hangs in the ceiling of the University of Washington boathouse. To make matters easier, the WinTech company had scanned another Pocock eight from 1937 that had survived at a US school and a detailed set of hull lines were available for Bill’s team to follow. All the details of the framing and fittings were worked out from many photographs of the original boat.

The day arrived for the first skin to be fitted and a small team joined Bill and leading boat builder Luan Qeloposhi in the vault. It takes many hands to handle such a long piece of timber ply without damaging it, so the process was carefully explained so that everyone would be able to act together. The long skin had already been cut to an approximate shape using paper templates, so it was quite easy to move it across to the frame and locate the top edge of the skin (the bottom edge in the photos as the boat is hull up while being built) in a loose slot along the outside of the frame. Then carefully pushing and bending the skin down over the curves of the hull, the edge of the skin met up with the keelson. Long timber battens held down with a rope zig-zagging along the frames helped to gently hold things in place.

Once he was happy with the alignment the first few copper nails were hammered in by Bill, then the team went to work. The slow curing polyurethane glue was already in place, so it was just a matter of fixing the skin with copper nails at regular intervals. Working in pairs to ensure the skin was held smooth and still while the second man swung the hammer, the nails went in at a fairly steady pace. There were a few problems along the way as copper is very soft and the occasional nail would bend – a problem exacerbated by the fact that the only available nails we had to work with were too long. Extra care also had to be taken in areas such as the footwell where the keelson had no framing to support it against bouncing with each strike of the hammer. However, with some care and the occasional use of a heavy brass buck (along with the occasional use of some fruity language) the entire length of the hull section was soon done.

The next process was to tidy up the edge of the skin along the middle of the keelson and then to pull the skin taut before then fixing it to the inwhales along the length of the boat. This was all to be repeated another seven times over the course of the next few weeks for not only was the boat being built as a sectional eight (the original was not sectioned) and thus requiring 4 long skins, but there were actually two whole eights being built. There was also an additional short straight section of hull made for ‘stunt’ work that would be required to recreate the moment when a press photographer in Berlin climbed under the boat to take a photo, and then stood up too quickly and split the hull (as mentioned in Chapter 16 of Brown’s book, but not in the film).

“Hands on”

It wasn’t just Mark and Bill’s team that was busy. Whilst all this was going on, a great many details were being worked on by others. The filming would also require a lot more than two boats, so a batch of 11 boats was made by WinTech using a specially printed fabric with a woodgrain effect that was laid up in modern moulds, with the framing then done in timber. These boats would be perfect ‘extras’ in the big scenes alongside the starring boats of full traditional construction. The beautiful brass oarlocks had also been sent to be cast and machined by WinTech.

The many oars needed for production were provided by traditional oar and spar maker Collars in Oxford. Although it wasn’t just oars for these two reproduction boats that were needed. The ten-boat race in the story meant that 80 period-correct oars would be needed. The team at Collars worked hard to meet this, with the older style of copper tips and leather sleeves once more becoming a familiar scene in their workshop. At one point the film art department realised that the busy pace of filming might mean that the blades of the oars could not be repainted quickly enough to represent all the different teams in the various racing scenes. So, another 80 oars were ordered. However, the team at Collars no longer had the time – or indeed the suitable timber – needed to make another 80, so it was agreed that another 40 oars would do!

Finishing touches

Although not actively involved in the final fitting out and finishing of the boats, I paid regular visits to check on progress. All the brass and leather fittings for the foot stretchers were fabricated, as were the period correct seats, wheels, and slide rails. It was a lot of fun to watch it come together. The two tone effect of the Western Red Cedar of the hull (custom made ply instead of the solid timber of the originals) and the pale Alaskan Yellow Cedar used for the saxboards all began to shine just like the original boat (as described in Chapter 8 of Brown’s book)

Many of the Pocock techniques and materials mentioned in the book can still be seen in use today by Pocock Classic, who use the original Pocock jigs and tools to make new boats. These are more ‘continued production’ boats than replicas or recreations. I visited the NW Maritime Center in Port Townsend a few years ago to see these magnificent new timber Pocock single sculls being made. For more details, see www.pocockclassic.org.

Testing times

When the time came to test the first boat on the water, it was hoped that a group of Master’s rowers from Twickenham Rowing Club (including myself of course) would come down to do this. However, one of the film’s producers wanted to be present and a suitable time could not be arranged. In the end the boat was launched with a crew consisting of the younger boat builders and a few mates from the Cornish gig club located at Richmond Bridge. I’m told that despite having Olympian Vicky Thornley on hand to coach it was all a bit exciting and fraught with danger for the crew who were completely unaccustomed to racing boats. As one of the lads later said, “The sliding seats make quite a difference!”

It wasn’t just the first ‘test’ crew of the boat that noticed the difference. Modern boats may look much the same in general layout to a 1930s vintage boat, but there are many differences in the rigging (length of rails, heights, work positions) that have changed over the years along with the techniques used to match this.

The story continues

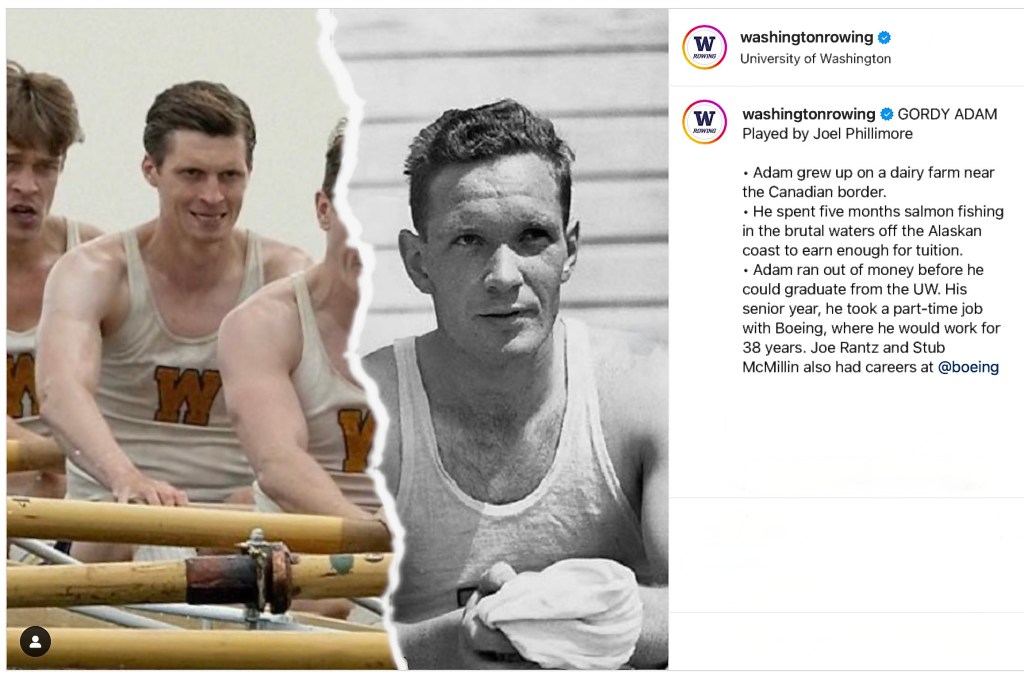

My part in this tale ends here, but I have been lucky enough to chat with one of the actors in the film, Joel Phillimore who played “3” man Gordy Adam in the film.

Joel takes up the story:

First meeting with the Husky Clipper

We were excited on the first day we were introduced to our Husky Clipper. We’d been rowing well as a crew for a few weeks by this point, rowing well at all eight, putting pieces together and generally starting to enjoy the experience of shifting a shell. So, we climbed into the wooden replica with a degree of confidence.

It didn’t take long to discover that this was a very different experience to rowing in a carbon fibre, modern shell. The angle of the riggers, the length of the track, the placement of the foot blocks were all completely different. I’m 6’6” and I couldn’t get my knees down despite hitting the back of the track at the finish. This combined with the much lower height of the rigger and gate meant that I couldn’t physically get my oar out at the finish, and needed to stay feathered until the final second at the catch. I caught so many crabs that I could’ve started a fishmongers. It took Terry O’Neil some late nights in the boathouse to make the necessary adjustments that allowed us all to translate what we’d learned in training to the new boat.

Enjoying the HC

Once we’d spent time with the Clipper, I think we all fell in love. It was a real privilege to row such a beautifully crafted shell. As we started to adjust our technique, figure out the sit and become more accustomed to her nuances we really started to enjoy each session on the water. The ‘hand-built’ qualities, the subtle details (like my ‘III’ on my stretcher), the sounds of the oars and the wooden wheels on the slide all contributed to make the experience truly unique – and for a history buff like me it was heaven.

Oars

We had a particular fondness for our individual oars. Each oar was numbered above the collar so we always had the same oar, but there were also ‘spares’ which would occasionally find their way onto the boat. We’d all know immediately if we’d been given a spare – the feel of the grain in the palm, the smoothness of the wood or the lack of months of accumulated grease and sweat. We wouldn’t have time to change the oar at these moments (when you’re needed on the water, in changeable conditions, you need to get there quickly) but as soon as we came in you’d see anyone with a spare jump out of the boat and switch it for the real deal. It sounds ridiculous, but with those wooden oars even a millimetres’ difference in diameter could be felt in the hand, or the absence of a grain that sat under the thumb could make the feather feel completely different. We were all gutted that we didn’t get to keep those oars – if anyone reading this knows where they are let me know please!

This article first appeared on Jonny Cantwell’s Flying Boatman Blog. HTBS articles on how wooden eights were traditionally built are here and here. A 2016 HTBS interview with Bill Colley is here.

What a wonderful commentary. Having last rowed in an VIII in the 1960s, I’m intrigued how boats have evolved.

John Beresford.

Speaks volumes for the film’s Art Department and Bill Colley etcs. attention to detail but , I wonder, what percentage of the viewing public appreciated same?

Bailey.

Bailey, at least we know it’s the “real” thing.

👍