28 July 2022

By Hugh Matheson

Hugh Matheson remembers Duncan Clegg, who died on 19 May, age 80. Glegg was involved in tremendous changes to both the Boat Race and to the British economy.

Male British rowers often divide their species into heroes and heavies. The heroes are you and me pulling our hearts out and winning fiercely competitive races by the skin of our teeth. The heavies, meanwhile, have worn callouses on their elbows from leaning on the club bar and opining about how they did it better. What ‘it’ is never matters very much.

Every river has them; heroes and heavies. Of course, most heavies think they belong in the hero class as they recall race day glory, but often they are stronger in imagination than they ever were in sinew.

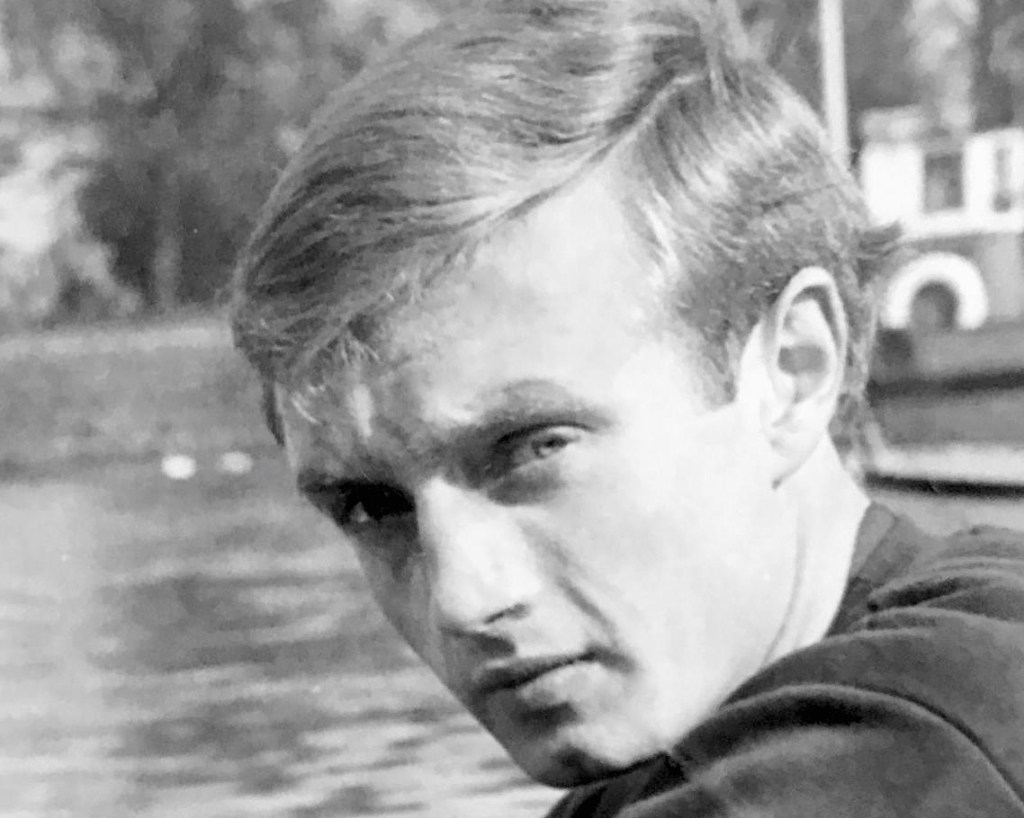

Duncan Clegg, who has died aged 80, ranked as a hero when he came from Tiffin, a rowing school in Kingston just upstream from the tidal Thames in west London, to St Edmund Hall in Oxford and rowed his freshman year in the Boat Race reserve crew, Isis, before two winning blues in 1965 and 1966.

In those years, the Amateur Rowing Association, ARA (now called British Rowing), had an informal first division with one club, Tideway Scullers, training at international level and three universities: Ox, Bridge and London, which aspired to gain selection for international racing. Spanning Duncan’s time, Oxford had sent its Boat Race crew from 1960 to race the VIII in the Rome Olympics and the London University VIII competed in Mexico in 1968.

To row in a winning Boat Race crew was to imagine at least, that you might also compete on the world stage. But Duncan, a planner who carried through life a clear and shrewd estimate of his value in any organisation, rarely overreached.

His first Blue came in the bows of a crew famous for the four Yalies: Ed Trippe, Duncan Spencer, Harry Howell and Bill Fink, who sat in the stern and provoked apoplexy in the Home Counties at the American takeover of a quintessentially British event. Now, the roles are reversed, and most Ivy League crews have a pronounced skew the other way, with big Brits crowding out the homegrown talent.

Duncan was light, 76Kg (180lbs), tidy in his watermanship and a dedicated puller. Then and thereafter, he was a character who believed that life’s rewards came from serious hard work. As the only blue likely to be ‘up’ at Oxford the following year, he was elected President of the OUBC for the 1966 race and immediately set about turning his inexperienced squad into winners.

He had some Isis caps from ‘65 and assembled a crew including another Yale American, Christian Albert, rowing in the four seat as part of a tandem with Jock Mullard at five. Michael Barry, a don at St John’s, who would deliver devastating criticism of rowing style and effort in the gentlest prose, was finishing coach and brought the crew to the Tideway as narrow favourites.

The crew was, like its President, well drilled, inclined to pull hard and with an understated aggression in its racing style. In the week leading to the race there were a couple of poor outings and Christian Albert grumbled that they could do better. Clegg took exception and believed that Albert’s attitude and rowing style were disruptive and that the crew would be more coordinated without him. After walking the towpath with Michael Barry agonising over the decision, but without discussing the matter with anyone in the crew, Clegg dropped Albert four days before the race. He was replaced in the four/five tandem with a home-grown Brit, Chris Freeman.

The high risk of replacing a key oarsman four days before the race was turned on its head 48 hours later, when Cambridge, rowing full tilt, were hit by a massive squall, shortly after starting a practice piece with Imperial College. The waves quickly filled the boat, which foundered and, being unsteerable, was blown across a buoy and broke in half.

The newspapers were filled with pictures of drenched rowers clinging to the buoy and jumping across the raging Tideway into the press and coaching launches, which fortunately were close enough to rescue the crew without any injuries.

Cambridge commandeered the boat used by their reserves, Goldie and their President, Mike Sweeney, claimed the accident would make no difference to their race pace or plan. Clegg’s crew, steered by their only remaining American, Jim Rogers Jr., got the better start and were one-second ahead at the Mile Post. Cambridge made a strong push at the Harrods Depository which provoked an Oxford response strong enough to give them a two-second lead at Hammersmith Bridge.

Oxford increased the lead to Chiswick Steps by enough to allow Rogers to steer across Cambridge and to take their water on the Middlesex station. They lead by ten seconds at Barnes and recorded a three and a half length win on the line at Mortlake. Isis, with a disgruntled Albert at five, won by twice that margin.

Twenty-five years later Rogers became famous for steering across another Cambridge man when, in partnership with George Soros, he bet against the Chancellor of the Exchequer Norman Lamont, late of Fitzwilliam College (1962), and sterling was ejected from the Exchange Rate mechanism. Rogers shared in the partnership’s £1Billion profit from that race.

Ever realistic and true to his plan, Duncan Clegg left Oxford and rowing, behind. With his degree in English at the core of his CV and after taking an MBA in Melbourne before becoming a merchant banker. He joined first, Samuel Montagu and later Lazards of London. His capacity to think through the strategy while being in command of the detail and his confident style on the microphone, meant that he rose to become a key banker in the privatisations of the late eighties. He did the water companies and was the public face of splitting the national electricity supply into twelve private companies.

In 1984, he reappeared, in a tie and blazer now, as the London Representative of the Boat Race. The Boat Race, which is arguably one of the biggest and best free sporting events, with four and a half miles of river crowded with spectators on two banks, few of whom have any direct connection with either university or rowing. The London Representative was like an impresario ensuring that the show went on, but the times were increasingly complicated and sensitive.

In his first race in charge, the Cambridge crew was steered by the cox Peter Hobson into a static barge in the final warm up 30 minutes before the start. The shell was wrecked. The race could not be rowed on schedule and the umpire, Mike Sweeney, (last seen marooned on the Black Buoy with another wrecked boat) met Clegg, the Police, the BBC and the Port of London Authority, which controls the river traffic, in the boatman’s workshop at the back of Barclays Bank Boat House. They had to make a quick decision: to cancel or go ahead at a different time or possibly even a different place.

Once the BBC team had gained consent to leave the outside broadcast kit in place for another 24 hours, the decision was taken by the group and announced by the London Representative that, for the first time in its history, the race would be rowed the following day, a Sunday. According to Sweeney, Clegg was cool and thoughtful throughout that test and quickly brought his impromptu board to a consensus and one which worked. The Sunday race was seen by 11 million people on television and brought gratification to the Oxford crew, which won in a record time. The sponsors were salivating.

For Clegg, his first decade in charge became more complicated by the year. The enduring sponsorships, first by Beefeater Gin and later Aberdeen Asset Management brought lots of money to the event which, in turn, meant many of the services which had been provided free in the fully amateur, shoestring days began to attract a charge. This put Clegg, a merchant banker, into his element. It capitalised on his knowledge of the race, its qualities as an event and his understanding of how fees might be negotiated and earned.

He and his predecessors as London Representative had tended to be well-off men working from fully functioning private offices, this resource became increasingly stretched and in 1990 The Boat Race Company Limited was formed to function as the executive. Very shortly after, a paid event manager was appointed and Duncan became Chairman of a board composed of representatives from both sides and particular elements of expertise on which the race depended.

Although the rowers were not paid, they were racing for boat clubs which were able to provide the best professional coaching, equipment, land training facilities, diet advice (these are students, some of them away from Mum for the first time) and physiotherapy to a higher level than most Olympic teams.

Before that dawn had risen, Oxford threw one major challenge to the reputation of the race. The dark blue run of ten consecutive race wins under the leadership of Dan Topolski, had ended in 1986 when two men who were to clash horribly a year later were in the crew. Donald Macdonald, a mild-mannered Scot, who had come to Oxford aged thirty, after a decade working in insurance, and a tall blond Californian Chris Clark were part of a squad which had begun to believe its own myth and let Cambridge get too far away to be overhauled and lost by seven lengths.

Clark returned a year later accompanied by three oarsmen and a cox who, he said, were the ‘rocket fuel’ required to get back to winning. Macdonald was elected President for the 1987 race.

After a Michaelmas term of patchy training, Topolski confronted Clark and told him he might not get into the crew on the evidence of his test results. The U.S. cohort was incandescent and thought they could challenge the authority of the President and his appointed coach.

The story of the Lent Term of 1987 and the race, which started in a thunderstorm of biblical intensity, has been told a thousand times on paper and celluloid. The role played by Duncan was in deep background, but vital.

When the rebels first challenged Macdonald, their intention was to form a crew based on their own selection, which would have Clark in and Macdonald out. Clegg from the first intimation of this plan made it clear to Oxford and, importantly to Cambridge, that the race would only be sanctioned between crews selected by each elected President and not by any breakaway group.

In spite of the clarity of this message, the manoeuvring, politicking and bullying went on for weeks before, eventually, the rebels retired and left Macdonald to lead a crew drawn from the reserves to a stunning victory.

Clegg’s style was of a strong spine inside a clean shirt and a Vincent’s tie. The establishment personified in a well-cut blazer, but his decisiveness and rejection of all the noise and nonsense, enabled Dan Topolski, an energetic, passionate Bohemian with a crumpled T shirt and a revolting, orange fur coat to work his magic for another – against all the odds – win for Oxford.

To any external eye, Clegg and Topolski were a bi-polar nightmare, but in 1987 and later as Stewards of Henley Royal Regatta, they worked closely together with benign good will. It is a credit to both that substance overrode style at every test.

The duty of the London Representative, or now the Chair of BRCL, is to provide the ordered framework for the Boat Race, which has no constitution, to function repeatedly and smoothly.

In the absence of a rule book, folk memory and an understanding of what is truly special in a nearly two-hundred-year-old institution, is key. Duncan had all of that and more.

In the late nineties, Mike Sweeney, who was at the time, a big cheese in FISA (now World Rowing), the international rowing body which stages the Olympics, World Championships and every other sanctioned international event, complained to Duncan that umpiring the Boat Race was becoming next to impossible and that he found himself warning one cox or another as many as fifty times around the long Hammersmith bend. The warnings were necessary because the umpire must decide where he thinks the stream is running fastest and to ensure that the crews get an equal share of the fast water by placing them either side of the centre line.

As Jim Rogers had demonstrated when Duncan was president, one crew can move in front of another and take its water provided there is no clash of hardware.

The umpire has the task of controlling two coxswains who carry the emotional burden of eight 90Kg balls of testosterone who are pulling for all they’re worth and won’t let them concede a millimetre. The umpire can shout cajole and threaten the coxes, but his authority is limited to the volume of his voice. Everyone from stem to stern in both crews knows that whatever happens they will not be disqualified. For all the huff and puff, the umpire is decoration not power.

Then, in 2001, Rupert Obholzer, a senior surgeon, Olympic medallist and former OUBC President, who knew the history of the race and the best course to steer as well as anyone, was umpire. Contrary to instruction, the crews moved closely together. The blades were clashing every stroke when a Cambridge oar was handled so clumsily, that it broke the gate and the crew stopped.

Obholzer halted the race, called Oxford back and ignoring the fact that the Oxford crew was about half a length ahead when the breakage occurred, ordered a restart with the crews level. Oxford’s restart was less good than their first and Cambridge capitalised before moving away to win.

Oxford’s rage may have added spice, but Clegg’s immediate response was to appoint Mike Sweeney to chair an Umpires’ Panel to set out the rules of racing, especially steering, that would henceforth govern the race and ensure that all accredited umpires knew how to handle all the situations which may arise. As ever the solution was practical, simple to execute and put the good of the race first, ahead of the hormones and the sponsors.

Duncan Clegg, as few others have, moved from hero to heavy with a stylish ease which used the knowledge gained as a racer to ensure the best conditions for his successors to flourish. In his fifty years of engagement, the Boat Race changed more in the way it was managed as an event and as a place for competitive individuals to burn off their aggression, than it had in its first 150. That he was in the lead for much of that change is a legacy worth remembering.

Robert Duncan Clegg, born 12 April 1942, died 19 May 2022. He is survived by his wife Jennie and their four sons, Robert, Edward, Alexander, Mark and eleven grandchildren.