3 January 2022

By Tim Koch

Tim Koch is visited by some unseasonal spirits of bump races past.

The Christmas and New Year holiday period is a time for sharing both real and imaginary stories and, in this spirit perhaps, Chris Partridge recently posted a true tale concerning Samuel Butler and a Lady Margaret Boat Club crew in a bump race at Cambridge in 1857. The charm of the story was not so much in the incident itself (when a rope caught in the future novelist’s rudder lines) but was more in the letter that Butler sent to his mother recounting the episode.

Chris’ piece reminded me of three of the many stories of bump racing incidents, tales that range from the fictional to the factual via the seemingly unlikely. Firstly however, a few explanations for those who are uninitiated into the mysteries of this peculiar form of boat racing.

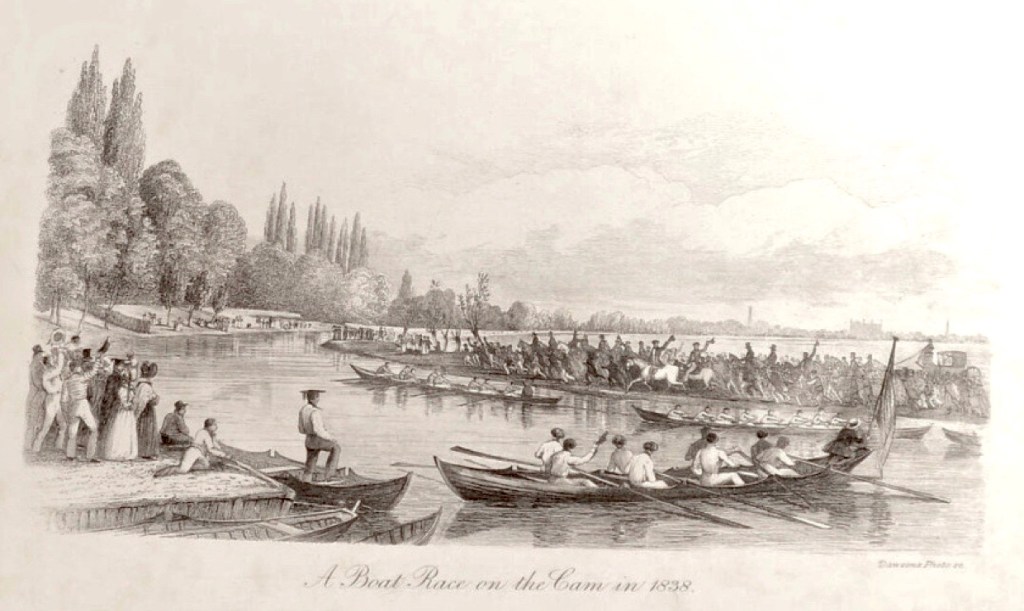

At both Oxford and Cambridge, there are two sets of intra-university “bumping races” for eights every year, one in early spring and one in early summer, all running over several days. At Cambridge, these are called “Lents” and “Mays” respectively, while at Oxford they are known as “Torpids” and “Summer Eights” or “Eights Week”. The crews are from the many colleges that together constitute each university.

The start of a bump race begins with perhaps 18 boats lining up about one-and-a-half boat lengths apart, their order depending on their performance in previous races. Posts are set along the bank, each with a fixed length of chain or rope with a handle or “bung” on the end. The cox must hold onto this bungline until the start signal is given, thus ensuring that all crews start from the correct position and at the same time.

The object of bump racing is to overlap the crew in front of you without being caught by the crew behind. Bumps are a continuous form of racing, so a boat’s start order depends on its finish order the previous day or, in the case of the first day, the finish order of their college’s equivalent boat at the end of the previous year’s racing. Thus, a boat’s chances of doing well depend not only on its current form but on the abilities of its predecessors as it is unlikely to go up more than four places in a year (except in Torpids which works differently). Getting to be “Head of the River” (i.e., top of the table) is a long-term affair necessitating a college putting out a strong boat year after year.

Samuel Butler’s boat was not the only one that had a memorable time during the 1857 Mays. According to WW Rouse Ball’s A History of First Trinity Boat Club (1908), on the second day of the 1857 bumps, the bowman of First Trinity’s fourth boat lost his oar when a bungline got tangled around it. Then, according to Rouse Ball:

Mr A. L. Smith caught up a spare oar, and at (Grassy Corner) threw it to bow, who although nearly knocked out of the boat by it, caught it, and rowed on. They made their bump opposite “The Plough”.

This story sounds slightly dubious but perhaps it is not as unlikely as it first seems. The boat would have had a fixed pin rowlock and, providing there was no twine over the top, it would have been easy to get an oar (once caught) back into action.

There is one bumps story that occasionally surfaces, usually in non-rowing circles, that is complete fantasy, a tale that probably originated in an inebriated undergraduate mind and that was no doubt subsequently embellished by some similarly inclined fellows.

The legend goes that, in the 1876 bumps, some oarsmen from St John’s College, Cambridge, attached a sword to their bow so that they would hole and sink any boat that they bumped. However, in the process of bumping Second Trinity, the bumped cox was run through by the weapon and killed. The alleged consequences of all this were, not a conviction for manslaughter as may be expected, but that both boat clubs involved were dissolved.

St John’s apparently dealt with their punishment by reforming under the name of “Lady Margaret Boat Club”. Any subtlety in this move was lost when they adopted blood red blazers to commemorate the stabbing incident. This apparently blatant example of hiding in plain sight is easily dismissed. There is no official or press record of the sword incident and, while it is true that a “St John’s College Boat Club” was disbanded in 1876, the original boat club at St John’s had always been called “Lady Margaret Boat Club”. It was founded and named in 1825 and its famous scarlet blazer dates from at least 1852. As they would have said in Cambridge at the time, quod erat demonstrandum.

Why the Second Trinity Boat Club, the innocent party, should have been dissolved is not clear. While it is true that the club was disbanded in 1876, it was for the prosaic reason that it was a club of theology students that proved unable to recruit enough oarsmen to justify its existence. The college still had two boat clubs however, “First Trinity” and “Third Trinity”, and they amalgamated in 1946 to form “First and Third Trinity BC”.

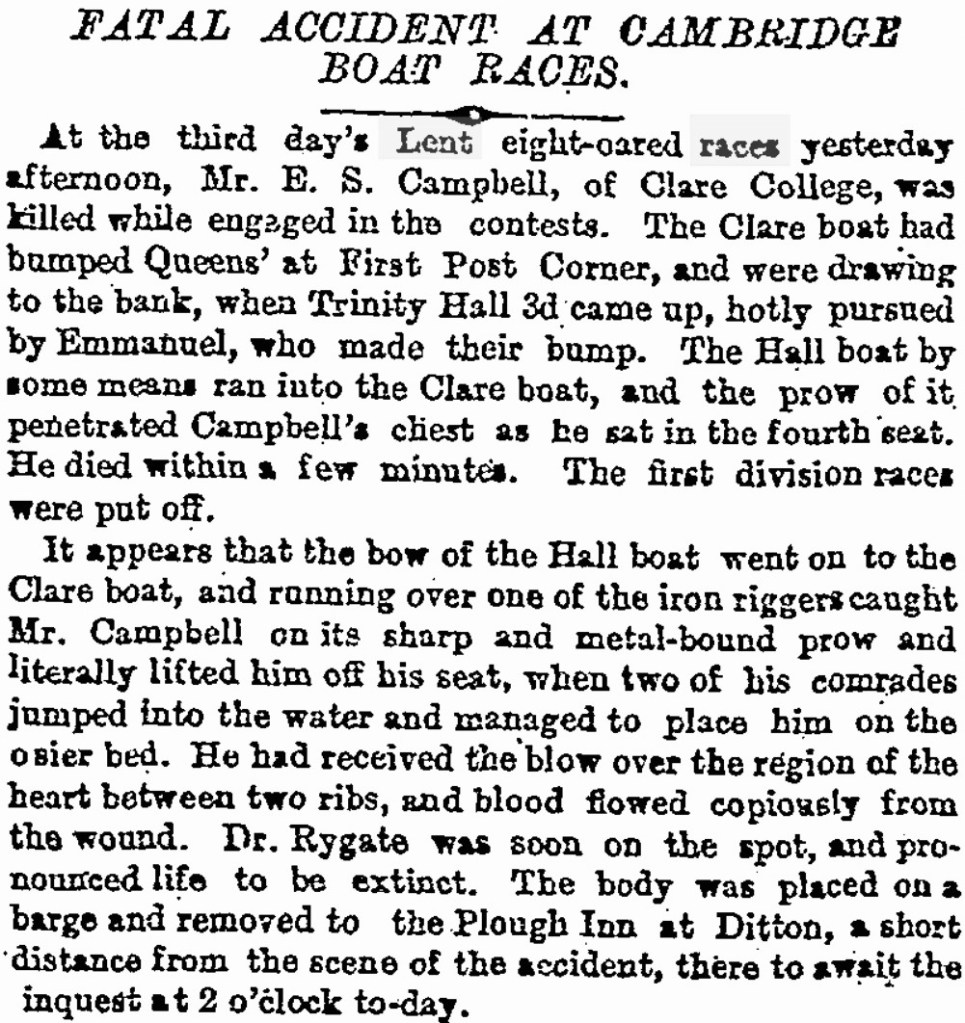

While no one knows when the story of the sword originated, it could have been inspired by a true incident that occurred during the 1888 Lent Bumps. Rouse Ball recorded that:

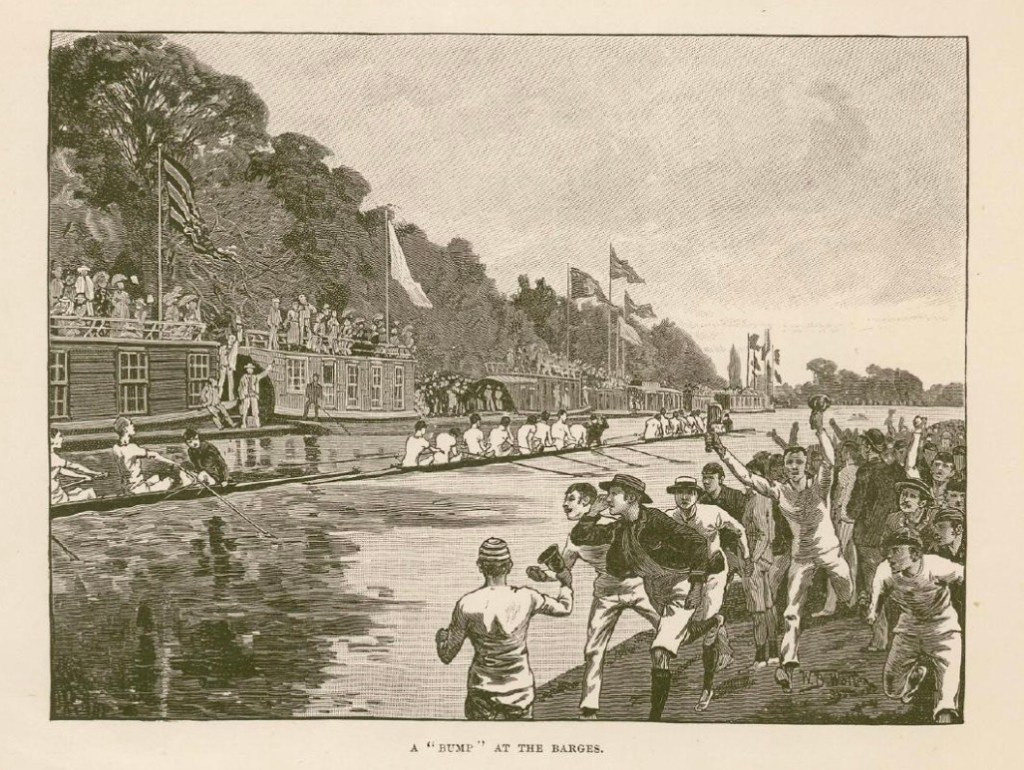

The third day was the occasion of a sad tragedy. Clare bumped Queens’, and drew into the bank by Grassy. Behind these boats was the Trinity Hall third boat. This, instead of rounding First Post Corner, ran, by some mishap, across the river, and the nose of the boat struck number 4 in the Clare boat just over his heart, killing him on the spot.

At the inquest, the coroner told the jury that he felt that there was no reason for them to consider a verdict of manslaughter. He continued that the college boat clubs should consider whether they should continue to have sharp-pointed bows to boats as they were clearly a source of danger. The jury returned a verdict of “Accidental death” and rubber bow balls were made compulsory on college racing boats.

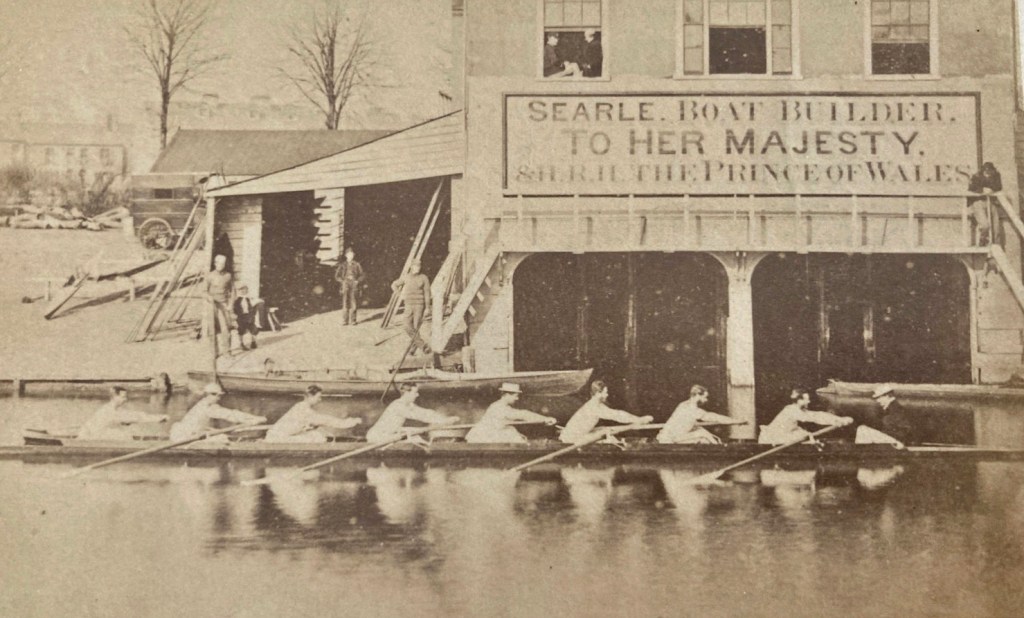

Looking at the pictures below (and viewing much more evidence on YouTube) it is perhaps surprising that there has only been one fatality in 200 years of bump racing. Like smoking, plastic and the internal combustion engine, were “bumping” invented today, it would quickly be banned.

* From ghoulies and ghosties

And long-leggedy beasties

And things that go bump in the night,

Good Lord, deliver us!

A Cornish Litany.

So in the very first bumps races (Oxford 1815, Cambridge 1827) how did they work out the order of line-up, without any previous history to base it on? Did they draw lots?