15 September 2019

By Tim Koch

Tim Koch looks at a remarkable member of a remarkable group.

Today, 15 September, is Battle of Britain Day. The Battle of Britain was the period July to October 1940 in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) defended Britain against large scale attacks by the Luftwaffe, the air force of Nazi Germany. The Royal Air Force Association website explains:

On 15 September 1940, the Battle of Britain reached its climax. The Royal Air Force shot down fifty-six invading German aircraft in two dogfights. The costly raid convinced the German high command that the Luftwaffe could not achieve air supremacy over Britain… needed for the invasion of the British Isles. Fighting continued for another few weeks, but the action on 15 September was seen as an overwhelming and decisive defeat for the Luftwaffe. For this reason, this date is celebrated as Battle of Britain Day.

The Battle of Britain and those who fought it have entered British national myth and the summer of 1940 is commonly held to be the ‘Finest Hour’ of a nation of plucky underdogs and backs-to-the-wall amateurs standing alone against ‘a new Dark Age’.

Some historians hold that the popular view misses out on many aspects of the Battle of Britain: ground support, radar and bomber command are rarely given enough credit; the British were never as short of planes and pilots as were the Germans; the Nazis made many tactical mistakes; perhaps the Royal Navy was a greater block to German invasion than was the RAF. Possibly the most pervading myth is that of the typical fighter pilot.

Historically at least, the British preferred their heroes to be square-jawed upper-class chaps who succeed without trying too hard. It is popularly imagined that the young, gallant and (in the parlance of the time) gay young men who piloted the Hurricanes and Spitfires were public school boys who treated the air war much as they would the Eton – Harrow cricket match or the Oxford – Cambridge Boat Race.

Like all myths, there is an element of truth in the popular image of wartime RAF pilots but, in reality, most were not ‘posh’. Recent research by a television programme found that of the 3,080 airmen awarded the Battle of Britain Clasp to their 1939-45 Star, only 141 (six per cent) were educated at the top public schools.

When the RAF and its precursor, the Royal Flying Corps, were formed, pilots were from the traditional ‘officer class’. However, with the rapid expansion Volunteer Reserve (VR) of the RAF in the 1930s, a new social class of airman was formed, the Sergeant Pilots, men who were not officers or even gentlemen. The VR attracted young working men out of grammar schools and technical colleges who wanted to learn to fly without having to pay. Public Schools and Oxbridge, with their emphasis on studying the past, did not produce the modern technocrats that the RAF required. Although some may have aped the slang and manners of the public school, most wartime pilots were educated by the state. At the time there were snobbish jibes that the RAF were ‘motor mechanics in uniforms’.

At least two literary giants, an arch-socialist and an arch-snob, proved to be strange bedfellows when they both recognised the RAF as an unlikely combatant in the class war. George Orwell noted: ‘Because of, among other things, the need to raise a huge air force, a serious breach has been made in the class system.’ In his novel, Officers and Gentlemen (1955), Evelyn Waugh has a character complain that a senior but unsuitable Royal Air Force officer has been allowed to join an exclusive members’ club. He explains that his membership was approved during the Battle of Britain ‘…when the Air Force was for a moment almost respectable…. My dear fellow it’s a nightmare for everyone.’

Having debunked the myth of the dashing public school and Oxbridge RAF fighter pilot – I am now going to perpetuate it.

In 1942, Flight Lieutenant Richard Hillary, a fighter pilot recovering from injuries suffered after having been shot down, published a book titled The Last Enemy. Hillary details his experiences from Oxford University (where he spent more time rowing than reading), to flight training, to his very brief combat experience that he had in the Battle of Britain before he was shot down and was horribly burned. He details his months in hospital as part of Archibald McIndoe’s ‘Guinea Pig Club’, undergoing pioneering plastic surgery to rebuild his face and hands and he describes the alleged epiphany that spurred him into writing The Last Enemy.

The war solved all problems of a career, and promised a chance of self-realisation that would normally take years to achieve. As a fighter pilot I hoped for a concentration of amusement, fear, and exaltation which it would be impossible to experience in any other form of existence. I was not disappointed.

On publication, The Last Enemy was met with instant acclaim. It was not, however, simply a tail of derring-do; it was literate, thoughtful, questioning and had depth. One of Hillary’s biographers, Denis Richards, wrote:

The author was acclaimed not only as a natural writer, but also as a representative of the doomed youth of his generation, although in his constant self-analysis he was in fact a most untypical British fighter pilot of 1940.

The great novelist, playwright and social commentator, J.B. Priestly, called Hillary ‘a born writer.’ One of his biographers, David Ross, said that ‘he was a writer who was a fighter pilot, not a fighter pilot that could write’.

Perhaps a typical Hillary piece is his thoughts on the first time that he shot down an enemy aircraft:

My first emotion was one of satisfaction, satisfaction at a job adequately done, at the final logical conclusion of months of specialised training. And then I had a feeling of the essential rightness of it all. He was dead and I was alive; it could so easily have been the other way round; and that would somehow have been right too.

After his crash, Hillary was patched him together ‘with inflexible features and contracted hands’. When he asked McIndoe when he could fly again, the surgeon replied, ‘The next war for you’. Somehow Hillary persuaded the authorities to allow him to fly again. Seven months after the publication of The Last Enemy, he was killed in an air accident. It is possible that his lack of manual dexterity was a factor in the crash that killed him. It was pure Greek Tragedy.

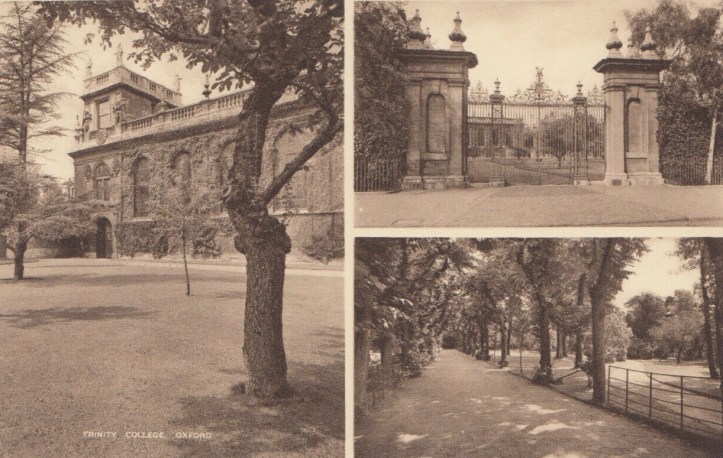

The full text of The Last Enemy is available online as part of the Project Gutenberg of Australia. Here, I am going to concentrate on the first chapter, partly because it is the only one that covers some of Hillary’s rowing experiences, partly because it is an interesting description of the mindset of many of the upper class young men who came of age just before the Second World War but who were brought up in the shadow of the First. His writing on the horrors of war in the later part of the book was a counterpoint to his description of the privileged life at Trinity in the late 1930s outlined in chapter one.

David Ross, author of Richard Hillary: The Definitive Biography of a Battle of Britain Fighter Pilot and Author of The Last Enemy (2003) gives a note of caution:

Details of Richard Hillary’s life have been hashed and rehashed time and again, regardless of inaccuracies. The main source of these works is ‘The Last Enemy‘ itself, which was also factually inaccurate partly because Richard was in America when he wrote it and did not have research sources available to him… ‘The Last Enemy’, beautifully written as it is, does not reveal the full story of Richard Hillary, partly because of the times in which it was written, and partly because he may not have wished it to.

In support of Ross’s warning on ‘inaccuracies’, many lazy Internet posts confidently state that Hillary was secretary of the Oxford University Boat Club. However, AB Hodgson held this post 1937 – 1938, FAL Waldron 1938 – 1939, and JS Stockton 1939 – 1940. It is also commonly said that he was ‘President of the Rugby Club’ though it is never clear if this was his college or the university club. Both seem unlikely when there is no record of him playing serious rugby and it would be strange to give the honorific title of ‘president’ to a first or second year undergraduate. I suspect that where these entirely avoidable mistakes originated from a single careless misreading of Hillary’s line that ‘(Trinity College) had the president of the Rugby Club, the secretary of the Boat Club, numerous golf, hockey, and running Blues and the best cricketer in the University.’

Many Internet (and other) sources also claim that, in his single operational week, Hillary had a not impossible – but very remarkable – five confirmed ‘kills’ making him an ‘Ace’. The Last Enemy is unclear on the exact number. He never received the Distinguished Flying Cross as may be expected with such a record and his Times obituary of 11 January 1943 makes no mention of them.

It must be remembered The Last Enemy was hastily written in the middle of a desperate war for the purposes of propaganda. Perhaps it should be called ‘a fictionalised memoir’. Ross quotes someone who had a letter from Hillary in which he referred to his ‘novel’. This does not make it any the less a work of literary merit or a study in self-analysis, nor should it detract from Hillary’s bravery, but, famously, ‘the first casualty of war is truth’. Any truth that survives the war is then often killed or wounded by unchecked cutting and pasting from the Internet.

Hillary fitted the fighter pilot stereotype. Born in Australia, his family moved to England when he was 3 and he never returned to the country of his birth. At the age of 8 he was sent to prep school, later public school, Shrewsbury, where he learned to row. David Ross quotes a schoolfriend of Hillary’s, Michael Charlesworth:

He was a very good oarsman. For two years he stroked the Second Eight… It seemed he either rowed stroke or not at all. Once he had applied himself to the task he gave everything… The coach in charge of the First VIII decided not to include him… I think that it was due to his attitude in general. He gave the impression that he was very ‘laid back’ and casual about most things…

In late 1937, Hillary went up to Trinity College, Oxford, to read History. His tutors were MW Patterson and JRH ‘Reggie’ Weaver. Of their teaching, it was said ‘Patters can’t and Reggie won’t’. Perhaps this lack of academic rigour gave him time to become stroke of the Trinity First Eight, a trialist for the Oxford Blue Boat and a member of the Oxford University Air Squadron.

Hillary went up to Oxford with some fairly standard plans and expectations for the time. Despite the strong influence of an English teacher at Shrewsbury, he was more hearty than aesthete.

The sentiment of (Trinity College) was undoubtedly governed by the more athletic undergraduates, and we radiated an atmosphere of alert Philistinism…. Trinity was, in fact, a typical incubator of the English ruling classes before the war. Most of those with Blues were intelligent enough to get second-class honours in whatever subject they were ‘reading,’ and could thus ensure themselves entry into some branch of the Civil or Colonial Service.… We were held together by a common taste in friends, sport, literature, and idle amusement, by a deep-rooted distrust of all organised emotion and standardised patriotism, and by a somewhat self-conscious satisfaction in our ability to succeed without apparent effort. I went up for my first term, determined, without over-exertion, to row myself into the Government of the Sudan, that country of Blacks ruled by Blues in which my father had spent so many years…

One of the great fears of upper-class Englishmen was appearing to be ‘too clever’ (though this was not a danger for many).

(Cleverness) would be tolerated as an idiosyncrasy because of one’s prowess at golf, cricket, or some other college sport that proved one’s all-rightness. For, while one might be clever, on no account must one be unconventional or disturbing….

Further, politics at Oxford in the 1930s was not as all-consuming as we nowadays may think.

No one could say that we were, in my years, strictly ‘politically minded….’ (One) could enter anybody’s rooms and within two minutes be engaged in a heated discussion over orthodox versus Fairbairn rowing, or whether Ezra Pound or T. S. Eliot was the daddy of contemporary poetry, while an impassioned harangue on liberty would be received in embarrassed silence….

Hillary claims that when he started writing for the Oxford magazine, Isis, it caused a change of mind about his future career.

I no longer wished to go to the Sudan; I wished to write; but to stop rowing and take to hard work when so near a Blue seemed absurd…. I dared not let myself consider the years out of my life, first at school, and now at the University, which had been sweated away upon the river, earnestly peering one way and going the other. Unfortunately, rowing was the only accomplishment in which I could get credit for being slightly better than average. I was in a dilemma, but I need not have worried. My state of mind was not conducive to good oarsmanship and I was removed from the (potential Blue Boat) crew. This at once irritated me and I made efforts to get back, succeeding only in wasting an equal amount of time and energy in the second crew for a lesser amount of glory…

I (also) felt the need sometimes to eat, drink, and think something else than rowing. I had a number of intelligent and witty friends; but a permanent oarsman’s residence at either Putney or Henley gave me small opportunity to enjoy their company. Further, the more my training helped my mechanical perfection as an oarsman, the more it deadened my mind to an appreciation of anything but red meat and a comfortable bed….

Despite these doubts, Hillary’s enthusiasm for rowing seemed little dampened. As war clouds gathered, he felt the urge to travel in Europe ‘before it was too late’ and worked out a cheap way of doing it: by taking advantage of the desire of authoritarian regimes to show off their ‘great achievements’ to the world. He wrote to the German and Hungarian governments asking that ten young gentlemen from Oxford may be allowed to take part in regattas in their countries.

They replied that they would be delighted… and expressed the wish that they might be allowed to pay our expenses. We wrote back with appropriate surprise and gratification, and having collected eight others, on July 3, 1938, we set forth.

Hillary’s account of the German trip is perhaps the least satisfactory part of his writing. It is a crude, stereotypical description of his German hosts, reminiscent of ‘B’ film Nazis snarling ‘Ze Geneva Convention means nothing here, Britisher pig-dog’.

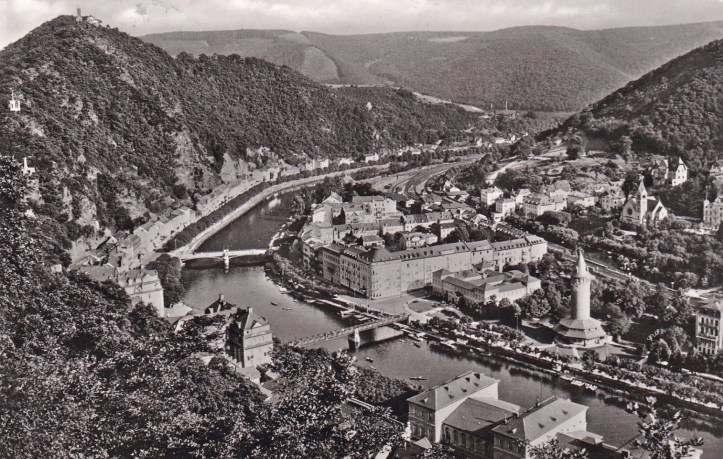

The first race was General Goering’s Prize Fours (formerly the Kaiser Fours) at Bad Ems on the River Lahn. Biographer David Ross says that Hillary intimates that he was one of the crew that raced in Bad Ems, but in fact he was one of the spare men.

(We) were regarded with contemptuous amusement by the elegantly turned-out German crews… great brown stupid-looking giants… (One of them said that he) had been watching us… and could only come to the conclusion that we were thoroughly representative of a decadent race. No German crew would dream of appearing so lackadaisical if rowing in England: they would train and they would win. Losing this race might not appear very important to us, but I could rest assured that the German people would not fail to notice and learn from our defeat….

Looking back, this race was really a surprisingly accurate pointer to the course of the war. We were quite untrained, lacked any form of organisation and were really quite hopelessly casual. We even arrived late at the start…

The way Hillary describes the race, all the German crews jump the start and by half-way the British are five lengths behind. However, he says someone spits on them from a bridge, they go mad and win by two-fifths of a second. I do not know how the whole crew knew that one of them had been spat on, and making up five lengths by force of anger seems rather unlikely, but the story probably went down well with non-rowing readers in the middle of a war.

The account of the Hungarian part of the trip sounds more credible, particularly to anyone who has experienced Magyar hospitality.

Members of our party had been dropping off all the way across Europe and it was only by a constant stream of cables and a large measure of luck that we finally mustered eight people in Budapest, where we found to our horror that we had been billed all over town as the Oxford University Crew. Our frame of mind was not improved by the discovery that we had two eights races in the same day, the length of the Henley course, and that we were to be opposed by four Olympic crews. It was so hot it was only possible to row very early in the morning or in the cool of the evening. The Hungarians made sure we had so many official dinners that evening rowing was impossible, and the food was so good and the wines so potent that early morning exercise was out of the question. Further, the Danube, far from being blue, turned out to be a turbulent brown torrent that made the Tideway seem like a mill-pond in comparison.

Long story short, Hillary’s crew lost due to ‘a combination of heat, goulash, and Tokay’. Davis Ross says that a photograph taken of the Trinity boat during the race shows Hillary at stroke.

Hillary had one final trip abroad before the war when the Oxford and Cambridge crews were invited to row on the bay at Cannes in the South of France and he was chosen as Oxford’s ‘spare man’, something he called ‘an enviable position’.

Cafe society was there in force; there were fireworks, banquets at Juan-les-Pins, battles of flowers at Nice, and a general air of all being for the best in the best of all possible worlds. We stayed at the Carlton, bathed at Eden Rock and spent most of the night in the Casino…

Hillary concludes the first chapter thus:

This, then, was the Oxford Generation which on September 3, 1939, went to war.

An account of Hillary’s finest rowing success did not find a place in The Last Enemy. Apart from rowing in the University Boat Race, the greatest achievement of an Oxbridge rower is to go Head of the River in the summer bumping races, something that Trinity did in Oxford’s 1938 Eights Week with Richard at stroke. The Times previewed the event by stating:

It is a long time since the standard in the first division was so high and there is very little doubt that

Trinity is the best Oxford College crew since the Christ Church crew of 1925… Although in very fast conditions, Trinity have reduced the record for the course, standing since 1920, from 6min 18 sec to 6min 8sec…. (They) are a very fine crew. There is no weakness in the bows, their leg work is exactly together, and they are a very powerful, hard-working lot. Hillary, the Shrewsbury second eight stroke, gives them good rhythm…

It may not have been all good rhythm. Davis Ross says that Hillary and bow man Derek Graham once had a fist fight but he does not say if it was over a rowing matter.

At Henley Royal Regatta in 1938, Hillary, weighing in at 74kgs, stroked a Trinity eight (the Head crew but with F.A. Loyd replacing R.C. Furlong) that won a heat of the Grand, and, in 1939, stroked a Trinity four that won two heats of the Visitors’.

In the run-up to the 1939 Oxford – Cambridge Boat Race, The Times reports show that Hillary took part in all the many Trial Eights outings and races held in November 1938 and January 1939. He mostly rowed in the ‘B’ crew in various seats but was once given the chance to stroke the ‘A’ crew. Ultimately however, he was not selected for the Blue Boat.

It is sobering to note the wartime fates of the Trinity College First Eight of 1938; it suffered a death toll more reminiscent of the First War than the Second.

Bow: D.I. Graham, RAF pilot, killed in a flying accident, October 1941.

2: A.O.L. Stevens, RAF pilot, killed in action, November 1940.

3: R.C. Furlong, Royal Artillery, killed in action, Netherlands, March 1945,

4: J.S. Stockton, Scots Guards, killed in action, North Africa, April 1943.

5: H.M. ‘Dinghy’ Young, RAF, killed on return from the Dam Busters’ Raid, May 1943.

6: F.A.L.Waldron, Scots Guards, twice wounded.

7: M.W. Rowe, Scots Guards.

Stroke: R.H. Hillary, RAF pilot, killed in flying accident, January 1943.

Cox: P.N. Drew-Wilkinson, RAF.

Centre: RH Hillary (Stroke). Front: HM Young (5), MW Rowe (7), PN Drew-Wilkinson (Cox), FAL Waldron (6), JS Stockton (4). Picture courtesy of Trinity College, Oxford.

The Trinity College archivist Clare Hopkins says of the above picture:

(It) is certainly one of the most poignant and iconic photographs in the Trinity College Archive. The six fallen men were among 133 undergraduates and alumni of the college – a remarkably high number when one considers that in the First World War the college list 159. Generally, casualties were much lower in the later conflict, which despite its horrors, at least lacked the carnage of the great set piece battles in the trenches. If you compare, say, village war memorials, you will see a much longer list for 1914-18. I have always believed that the reason for the high number at Trinity College was that so many members served in the RAF, where life expectancy was just so short.

Clare’s observations bring us to a final thought. The Last Enemy takes its title from Corinthians: The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death.