15 May 2017

Tim Koch looks at a glamorous family and their difficult relationship with Henley Royal Regatta:

It is famously said that often, ‘life imitates art’. However, it is sometimes more accurate to say ‘life imitates bad art’. Occasionally, a real life story emerges that seems to be such a collection of clichés that, were it presented as a work of fiction, it would be dismissed as lazy and hackneyed, fit only for the most undemanding market. One story that appears to have come from the asinine imagination of a Hollywood hack – but which is, in fact, true – is that of the Kellys of Philadelphia.

In 2014, HTBS reported that a film of Dan Boyne’s book, Kelly: A Father, A Son, An American Quest (2008) was ‘in development’. Nothing seems to have happened since then – but it must have been an easy movie to pitch to the producers. In the Kelly saga, John ‘Jack’ Brendan Kelly Sr, one of nine children of poor Irish immigrants, becomes a sporting hero, a millionaire businessman and a classic American patriarch. However, the haughty English establishment (allegedly) robs him of Henley glory – but he gets revenge three times over when he beats their man at the Olympics and when his handsome son, Kell, twice wins the prize denied to him. Further, his beautiful daughter, Grace, becomes an Oscar-winning Hollywood movie star and marries a Prince. Years later, all is apparently forgiven and Henley names a race after the Princess. Roll the credits…

Henley Royal Regatta, 1920

Jack Kelly (1889-1960) was a tough man. At the age of nine, along with his four brothers, he began working 12-hour days in a woollen mill. Competitiveness and self-belief had been bred into the Kellys, and two of Jack’s brothers also later found success, George as a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and Walter as a vaudeville actor. In 1907, at the age of 18, Jack took up the two things that would shape his life: rowing and bricklaying. Brickwork helped physically built him into a superb athlete, and when he later started a brickwork contracting company, it provided him with his considerable fortune. As to his activities on Philadelphia’s Schuylkill River, by 1916 Jack was a national champion and the best sculler in the United States, already well into his 126-race winning run. He saw service in France in the 1914-1918 War (though it was the 1917-1918 War as far as America was concerned) and rose from private to lieutenant. In the army, he discovered a talent for boxing and after the war he played professional (American) football for a season. He was later to prove equally robust in U.S. big city politics, promoting the Kelly family as Philadelphia’s answer to the Kennedys of Boston. However, it was sculling that was his real love and, having won six U.S. National Championships, by 1920 he was ready to take on the world. He could do this either at that year’s Olympic Regatta in Antwerp, Belgium, or at that year’s Henley Royal Regatta in England, still regarded by many as an event superior to the upstart sixth Olympic Games. Jack was one of ‘the many’ and set his sights on Henley’s Diamond Sculls, a prize that he had dreamed about even before the war.

However, Jack knew that there was a problem concerning his ambition to win the Diamonds. He had no doubts about his ability to beat any other competitor, but he did question his ability to enter the race in the first place; he was aware that there were two possible barriers to his taking part in the famous event. His previous work as a bricklayer seemed to contravene Henley’s ‘manual labour rule’ which classed anyone who ‘is or has ever been… a mechanic, artisan or labourer’ as a professional and therefore ineligible to compete. Also, Jack’s Philadelphia club, Vesper, was still technically banned from Henley following the 1905 regatta when they breached the rule on using a public subscription to raise travel money. In his history of Thames Rowing Club and Tideway rowing, Hear the Boat Sing (1991), Geoffrey Page wrote:

In the 1950s (Kelly) wrote to Jack Beresford, the winner of the 1920 Henley Diamond Sculls race, the following: ‘Russell Johnson, secretary of (the governing board for U.S. rowing) had an arrangement with the Henley officials that they would approve all entries from the United States….. I asked him to check with the Stewards to see if they would accept my entry because in my earlier days I had served an apprenticeship as a bricklayer. He contacted four of them and they told him to send my entry in; the war had changed the old rule and everything would be all right’.

However, everything was not ‘alright’ and when Jack’s application was formally considered, it was rejected. Kelly’s Wikipedia page quotes the minutes of Henley’s Committee of Management for 3 June 1920, 27 days before the start of the regatta:

The list of entries … outside of the United Kingdom under Rule iv was presented … and received with the exception of Mr J.B. Kelly of the Vesper Boat Club to compete in the Diamond Sculls, which was refused under the resolution passed by the Committee on 7th June, 1906….. ’That no entry from the Vesper Boat Club of Philadelphia, or from any member of their 1905 crew be accepted in future’. Mr Kelly was also not qualified under Rule I (e) of the General Rules (manual labour).

Communicating this news was done badly and made an unpleasant situation worse. In his Henley Royal Regatta: A celebration of 150 years (1989), Richard Burnell says that only two days before Kelly was due to sail to the UK, he received a telegram which said, ‘Entry rejected, letter follows’. Jack held that he never received a letter. The Henley Stewards claimed that they had informed the governing board for U.S. rowing in good time but the American administrators had not passed the information on to Kelly (though it could be asked, if Henley did write in time, why did they then send the last-minute telegram)? The incident generated a lot of heat and very little light on both sides of the Atlantic, fuelled by British suspicion of U.S. ideas on amateurism and by American-Irish Catholic’s scorn of anything to do with the English establishment.

Poor communication aside, Henley was technically correct in applying two clear and long-established rules. However, they ignored Henley’s Unwritten Rule: Stewards make the rules and can do what they like. There were at least two precedents in ignoring the manual labour clause. Harry Blackstaffe, a butcher, competed in the Diamonds in 1905 and 1906, and Wally Kinnear, once an apprentice blacksmith, raced his single at Henley in 1910, 1911 and 1912. As to Vespa’s 1905 ban, with the establishment of the Stewards’ Enclosure, Henley had already acknowledged that the Great War had changed many things and it would have been reasonable for it to decide that 15 years exclusion was enough punishment. Although entries from Boston’s Union Boat Club for the Grand, Stewards’ and Diamonds were accepted, it is difficult not to conclude that this was an attempt to stop the Diamonds from going abroad.

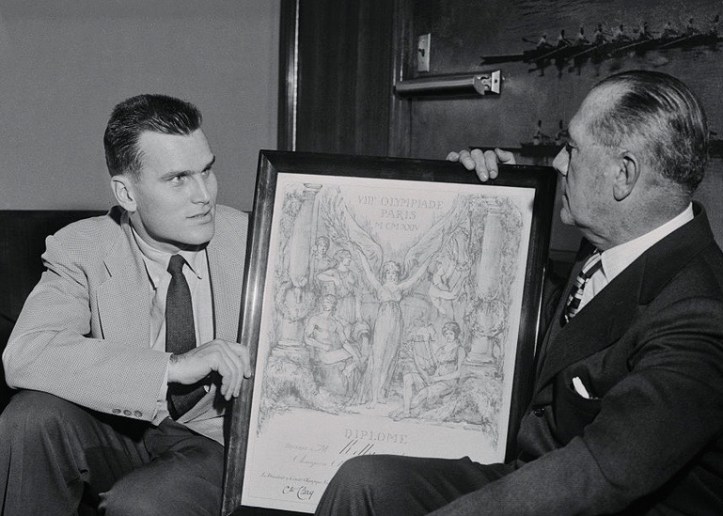

Kelly famously got some revenge by beating the British winner of the 1920 Diamonds, Jack Beresford, by one second at the 1920 Olympic Games. He confirmed his talent by winning the double sculls only half-an-hour later and, on his return to Philadelphia, he was greeted by a crowd of 100,000. Jack won in the double again at the 1924 Paris Games but he was never to race at Henley – that was to be the task of his son, John Brendan ‘Kell’ Kelly Jr. (1927-1985). Jack made it his mission to mould Kelly Jr. into a rower. Kell did not share his father’s natural talent but he was a good athlete and he later said, ’My old man pushed the hell out of me’.

Perhaps there was another legacy of Jack’s clash with ‘amateurism’. In 1970, Kell was elected president of the Amateur Athletic Union and stirred controversy by arguing that the amateur code had become outmoded and he pushed to free the Olympics from ‘sham amateurism’.

The first Henley after the 1939-1945 War was set for 1946. Kell had won the 1945 Junior National Championships in America and in Canada and, at a regatta in June, he had won five events, junior and senior, in three hours. When he reached 18, he had to do his military service, but the U.S. Navy based him in Philadelphia and allowed him time to train. Twenty-six years after the first attempt, a Kelly was finally going to race for Henley’s Diamond Sculls.

Part 2 continues the story tomorrow.