31 October 2016

Tim Koch writes:

In 1908, an anthropomorphised water vole, speaking in a pastoral vision of Edwardian England, summed up the appeal of a craze that was taken up by all social classes and which lasted from the latter part of the nineteenth century until the dawn of the Second World War:

Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing — absolutely nothing — half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats. Simply messing….. about in boats — or with boats. In or out of ‘em, it doesn’t matter. Nothing seems really to matter, that’s the charm of it.

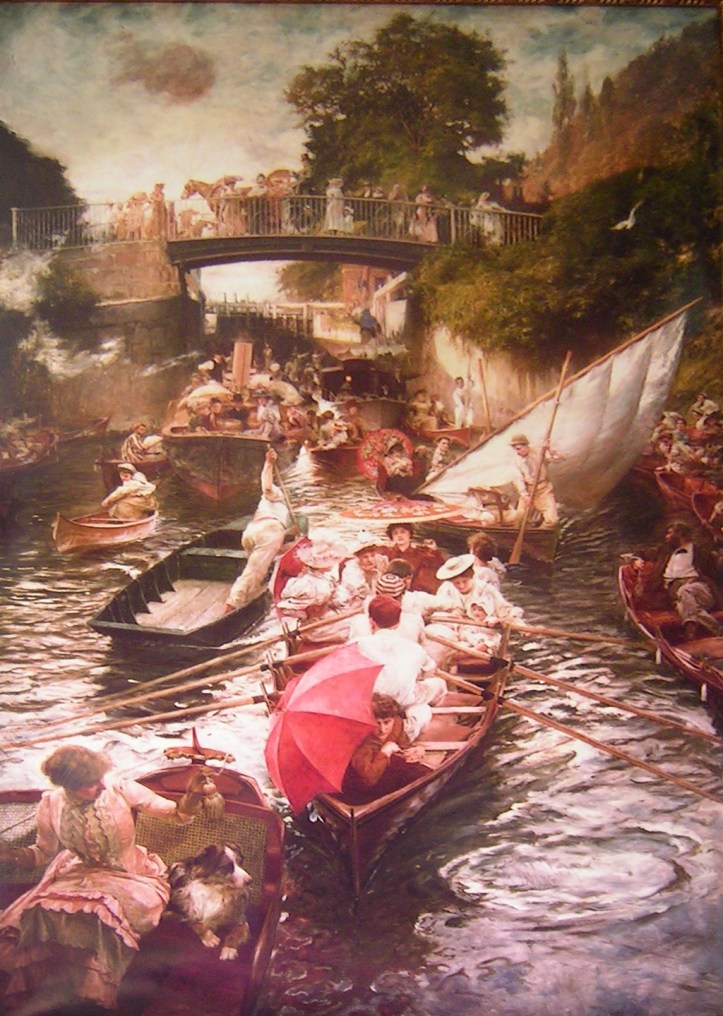

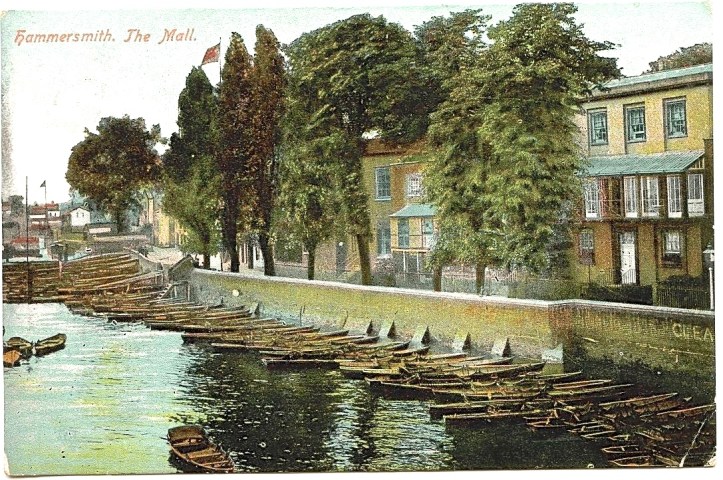

In Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows, Ratty, Toad, Mole and Badger joined the millions who, from the late Victorian age and into the Jazz Age, were determined to somehow get afloat whenever finances, leisure time and summer weather allowed. For over 50 years, Britain was ‘boating crazy’ and enterprising people in river and lakeside towns all over the country built and hired craft such as skiffs, punts and canoes to satisfy the demand for recreational aquatics. The best known illustrations of this mania are shown in almost any pre-First World War photograph of the river at Henley during the Regatta and also in Edward Gregory’s famous painting of Boulter’s Lock at Maidenhead on a summer Sunday in the 1880s or 1890s. There are also, however, many less well-known depictions of the long-lived boating boom.

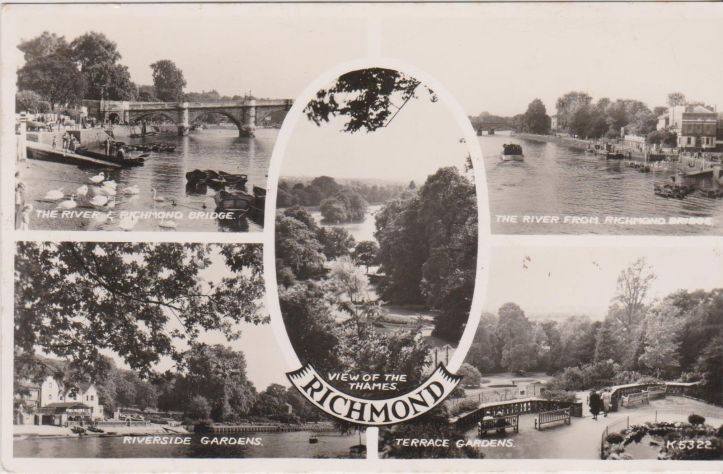

The boating craze only semi-recovered after the 1914-1918 war and was killed off almost completely by the 1939-1945 conflict. Nowadays, it is true that rowing boats can be hired in the summer for an hour or two in a few places such as Windsor or Henley, but they tend to be of the uninspiring ‘plastic’ variety. It was thus with great delight that I recently visited the suburban town of Richmond, Surrey, where I found a little of the ‘Golden Age of Boating’ still in evidence. Officially Richmond is in ‘southwest London’ but the locals like to think of it as ‘southwest of London’. The prosperous town, which has a number of parks, open spaces and protected conservation areas, is on a meander of the River Thames and is home to the oldest surviving Thames bridge in London, the 300-foot span having been completed in 1777. Today at Richmond, not only is it possible to hire skiffs such as the Victorians and Edwardians would have known, it is also home to two builders of wooden boats (Mark Edwards and Bill Colley) and to two boat clubs that use traditional craft (the Richmond Bridge Boat Club and the London Cornish Pilot Gig Club). Further examination of any one of these is a full article in itself and is for the future but, for now, I will limit myself to writing about why I went to Richmond and also to sharing the wonderful talk that I had with wooden racing boat builder and designer, Bill Colley. First though, a little pictorial evidence on how the boating scene at Richmond has survived the ages.

I went to Richmond on 21 October at the invitation of HTBS contributor, Clive Radley, to witness him ‘rechristening’ a sculling boat, originally built by his uncle Sid in 1956, and recently fully restored by Bill Colley. Clive is the author of The Radleys of the Lea (2015), the story of his family’s involvement with boatbuilding and rowing on the River Lea in East London. He described the book in a HTBS post in March 2015:

The book “The Radleys of the Lea” is the story of my ancestors whose boatyard business was founded in 1840 by my great-great-grandfather George Radley and his wife Phoebe. The business flourished by the River Lea in northeast London for 130 years and at its peak in the early twentieth century there were three boatyards, all a few miles upriver of the London Olympic Stadium site, between Lea Bridge and Springhill…… The book includes the history of the boatbuilding business and the rowing exploits of family members. Boatyard life in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is described, as well as the way in which the social and geographic conditions of northeast London and northwest Essex influenced the founding of the Radley business and its subsequent development….. I was born in 1945 and grew up in Leytonstone in northeast London and quite often my father would take us by bus to visit my uncle, Sid Radley, our last boat builder….. These visits resulted in an interest in rowing and boating which I have retained throughout my life, ultimately leading to this book.

Clive posted the full story of the Hopper on HTBS in September 2015 but I shall attempt a summary.

Roger Bean rowed at Hexham on Tyne and other Northern Clubs between 1958 and 1980. He returned to the sport at Durham in 2012 and, on a visit to his old club, found a dilapidated scull, then named J. Hopper. It was holed, had peeling varnish, was missing its riggers and seat, and was almost certainly destined for a bonfire. The boat was named after the eminent Hexham-based professional sculler of the 1920s and 1930s, Jack Hopper, who had competed against Roger’s grandfather, Tom Bean, and had also raced the great Thames professionals of that era. Thus, in a nostalgic and rash moment, Roger bought the boat for £50. He had only restored vintage motorbikes before but, making a very long story very short, by September 2014, he had got the Hopper to a state whereby it could go afloat for the first time in many years. After ten minutes of sculling, the boat did not actually sink but it did take on a lot of water. Thankfully, Roger and the 56-year-old craft made it back to the pontoon.

Roger’s researches up to that point had found that a pair of matched scullers were bought by Hexham Boat Club (as it was then) in 1960 from a London source and one, the Maxwell, was re-named after Hexham’s most famous son, Jack Hopper. This was fortunate as the boat probably only survived because of the connection with Jack’s memory. They were described as ‘ex-Doggett’s Coat and Badge committee boats’. As ‘Doggett’s’, the 300-year-old sculling race held annually for up to six newly qualified Watermen, abandoned the practice of providing competitors with boats in 1960, this would make sense. An article later found in the archives of an East London newspaper, The Stoke Newington Observer, dated 27 July 1956, confirmed that, in two months in 1956, Sid Radley made six sculling boats at £100 each for use in the Doggett’s race.

In November 2012, Roger contacted Chris Dodd at Henley’s River and Rowing Museum (RRM) for information on ‘V. Radley and Sons’, the name on the maker’s plate, and, naturally, he was put in touch with Clive, the Radley family historian and nephew of the builder. Roger wished to give the Hopper to the RRM but Clive probably correctly guessed that they would not consider taking it in its semi-restored state and so offered to fund the boat’s full restoration by Bill Colley. On this news, the museum accepted it, ‘sight unseen’. I think it is of great credit to the RRM that they should take something that is only really ‘special’ in that is one of the few surviving examples of an inexpensive, almost ephemeral boat that gave untold hours of pleasure, mostly to very ordinary people who had very unremarkable rowing careers. It is as much a part of the story of rowing and sculling as any of the museum’s more obviously historic craft that won ‘great races’ powered by ‘great men’.

I talked to Bill Colley about the restoration, starting with the question, ‘what did you think when you first saw the boat?”

Not a lot honestly…. it was unbelievably heavy…..When I started to take it apart, it did not improve, everything was broken, everything had to be reglued and the varnish work….. all had to be scrapped off….. I employed a young lad to do that, they’ve got more patience, the young….. It is not a remarkable boat apart from the fact that it is now rare…… It has cedar planking, the saxboards are mahogany, the ribs are sycamore, and everything else is spruce…. that’s how they were…..

In Part II, which will be published tomorrow, I talk to Bill Colley about his remarkable 65-year career in traditional racing boat building.

Amazing article about Richmond and J Hopper acceptance ceremony.

Anybody remember Peter Gordon Killik who rowed at Richmond Rowing club in the 1930s?