Laurie Radley, one of the members of the Radley Family of Lea, retained vivid memories of his childhood and early working years by the Lea at a Radley boatyard in NE London. When he was 84, in 1990, he put pen to paper and wrote a description of those early years by the Lea and of UK rowing and the boatbuilding scene. He produced three hand-written versions and these were edited by Christopher Dodd of the Henley River and Rowing Museum in 2001-12. Clive Radley, Laurie’s nephew and author of The Radleys of the Lea, has done some further editing to produce this article and added a number of pictures.

Earliest Memories pre-World War I

Laurie’s words:

My family were the principal boatbuilders, owners and hirers on the River Lea at Clapton, east London. We had three boathouses: the Old Boathouse just south of Lea Bridge at Lea Bridge dock, the New Boathouse north of Lea Bridge at Lea Dock, and a pleasure boat hire/tea room operation at Springhill. Springhill was a lock-up affair with a night watchman.

My earliest memory is being in an open sculling boat propelled by my father, Wallis Radley, en route to the New Boathouse. I must have been about 4 years old as I had not started school. I helped out in a small way, I was a very young apprentice. This was before the 1914-18 War – I was 8 years old when the War started. I had an occasional job to row a large fat man (Billy Prior) up river about half a mile to a riverside pub where he would have a drink, and 1 would row him back. He weighed about 20 stone. We were evidently one of the sights, big Billy and little me. I was about 6 or 7 – I got sixpence, a lot of money in those days.

My family operated a ferry across the river, a large punt propelled by a single oar over the stern called single oar sculling. I used to help Mr. Ford, who operated the ferry. As he came alongside, I would slip a loop of chain over a peg on the side of the punt. I was swinging on the chain one day and I swung round straight into the river. I can remember watching bubbles rising from my mouth until a hand grabbed me and hauled me out. I lost that job.

At that time, on a fine Sunday or Bank Holiday, there were probably a hundred boats on the river between Tottenham and Old Ford locks. By agreement, no racing boats were allowed on the river on Sunday afternoons or bank holidays. Milk was a favourite drink after a hard training spin, hot in winter, cold or with soda in summer, R White’s mineral water, and a drink peculiar to the area, Tucks Sarsaparilla, which was brewed by Bedells, a local chemist and herbalist. There was a large variety of cakes, cheesecakes, Banbury cakes. My favourite was a round currant cake nicknamed a Buster; one of these and a glass of Sarsaparilla made quite a meal for a youngster.

Springhill was for pleasure boats only and the pre-War trade was good class, and the upper Clapton Stamford Hill area was a good class residential area. Most of the customers could be relied upon the handle the boats properly. We had skiffs with wooden rowlocks, Canadian canoes, and a single canoe built of wood, decked in fore and aft, rather like a kayak known as a Rob Roy canoe. They were safe if handled properly, but could be capsized by accident. We always sought assurance that the customer could swim. During the War, a lot of people in Clapton moved away to be replaced mostly by refugees from Europe. Someone drowned in one of the Rob Roys so Dad had to get rid of the canoes. The wooden rowlocks had to be replaced with metal rowlocks as they being broken. Also, we had to ask for a deposit when a boat was hired.

Grandma Martha Radley managed the Springhill site. We would have to wait until the last boat was in, then we would row Grandma home to the main boathouse in a randan, a lovely triple rowing skiff. Grandma would sit in the stern seat looking like Queen Victoria, but unlike that great lady, she was always amused.

My grandfather, Vincent Radley, was a great gentleman, a strict disciplinarian, but kind with it. A friend of his was a theatrical agent who got Buffalo Bill’s Circus to come over. Grandad was introduced to him. He had a portrait of W S Cody which used to hang in the refreshment room. It was signed. There was also an Indian tomahawk and a bow and arrow. Grandad was keen on western books. Nobody went home until the last boat was in and Grandad had left his little office. If he was reading a Buffalo Bill book, we would sometimes have to wait until he had finished before we could go home. I would get the books when he had finished them.

Clive Radley comment: Laurie’s father, Wallis George Radley, had served a waterman’s apprenticeship under the famous John Thomas Phelps pre-World War I. Sadly, he did not compete in the Doggetts Coat and Badge Race. It is assumed he was eliminated in a qualifying heat.

Clubs on the Lea

Tyrells Boathouse at Springhill boathouse had a number of clubs based there: the Iris RC, the Gladstone and Oxford House were the main ones, also later the Borough of Hackney.

There were a large number of rowing clubs which originally came from different districts of East London. Clapton Warwick drew their members from the immediate area of Lea Bridge – they were the most successful club and also ran a very good football team. The Clapton Zephyr came from a different part of Clapton. There was the Tiger RC, University RC, Oxford Mission, Dalston Alberts, two clubs from the GPO sorting office at Mount Pleasant (Spartan RC from the home section, Alliance RC from the foreign section); Lea Bridge, a professional club started by my father. Royal London Insurance had a small club. After the War, we had N Division and H Division of the Metropolitan Police and the London Fire Brigade (LFB) had a club. The LFB used to welcome ex-naval men to join because of their general fitness and ability to climb. The London General Omnibus Company which eventually became London Transport had a contract with us, paying a fixed sum yearly and had right to use the racing boats at any time. The Amalgamated Press, the City RC (a shirt manufacturers from the City), and the Orient RC which eventually merged with each other. My two younger brothers rowed for City Orient.

ARA and NARA and Lea Course

There were two rowing associations, the ARA open only to [amateur] professional classes, universities, colleges etc. Anyone working with their hands, no matter how skilled, was banned. The big Thames regattas were barred to them, so the National Amateur Rowing Association (NARA) was formed, open to anyone except professionals. Most of the clubs on the Lea were NARA. There were some Amateur Rowing Association (ARA) clubs, but a lot of men who could have joined the ARA clubs preferred the NARA as there was more activity.

There were a number of events, starting with the President’s Cup for novices, in those days. This was rowed in what was known as chock fours, an in-rigged boat with wooden rowlocks. There was always a large entry for this event. Crews would train in the dark through the winter. The river had lights on the Middlesex side as far as Springhill, about a mile and a half. Coxswains were instructed to keep strictly to the left and to call out at intervals. The crews were very keen; we had one crew training at ten o’clock at night because one member worked late. The main regatta was over five evenings, with the finals on Saturday. They would row their guts out just for the honour of winning for their club. There was great rivalry between our clubs, V Radley and Sons and Tyrells at Springhill.

The senior course was about a mile and a half starting at Baileys Lane. It was a difficult course to steer, there was a sharp bend at Springhill, a short straight, than an S bend at Frenchman’s Point, another sharp bend at Robin Hood point, then the railway bridge, another bend, then a slight bend at the beginning of our boathouse, then a short sprint home. Considerable skill was needed to navigate this.

There was a rule in both associations which declared that anyone working in or about boats was a professional. This included lightermen and sailors. Wherever there were boats, there were highly skilled men, the boatmen. School and club boatmen were a knowledgeable body of men. Families I knew included the Tallboys, Harrises, and Andrews at Oxford, the Cobbs and of course the famous Phelps family of Putney. My family were the Radleys of the Lea and from a very early age we were skilled in the use of all types of boat.

Post-World War I Activity and Personalities on the Lea

The immediate post-war years were very busy with young men who returned from the war (a lot didn’t). 1919 was a fine summer; parties of young men would stroll along the towpath singing in harmony. Everybody wanted to sing, harmonising was enjoyed by the young people, and also yodeling was a favourite. One tall young man had a beautiful voice, and we could hear him for miles on the river.

Club rowing resumed after the War. The men who returned were mostly all right. Mac White, a fine oarsman and athlete, had been gassed and had periods when the mustard gas would cause him some distress. Mac was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM). One of his closest friends, Joe Allen, a fine sculler, would be racing when he would suddenly have what looked like a fit. He was x-rayed and they found that he had a piece of shrapnel in his bottom, which when he rowed, pressed on a nerve causing him to pass out. Another young man, Bert Devereaux, worked for us after the War. Bert was a fine oarsman, also a top class sprinter. The officers of his regiment threw out a challenge for him to race against Paddock, the American Olympic athlete who was with the Americans in France. Bert rowed for our club as a professional. He suddenly started to deteriorate with what seemed to be a form of creeping paralysis. The doctors said if he had been wounded it would have got rid of the terrible tension of five years of War.

Another young man, Harry Hill, who managed our boathouse at Springhill until he got going in his own trade of tailoring, had been wounded by a sniper and taken prisoner. When he came home he still had two bullets left in – the point of one could be seen pushing the flesh of his bicep. Another man, Charlie Tugwell, who rowed for the Iris RC at Tyrells boathouse, had lost a leg. He was a fine sculler. As the regatta was held from our place, Charlie kept a spare pair of crutches at our place. He would have his artificial leg in the dressing room, walk down on his crutches and get into his boat with a little help from one of us. He was still a good sculler, but tired quickly. Quite a few men seemed to crack up after seeming to be OK. Bill and Alf Parrot, who used to work for the firm, rowed in a four with my father at Staines Town Regatta in 1919, winning senior fours. Bill developed neurasthenia and Alf felt the effect of his War wounds. They were fine oarsmen and had terrific guts. Bill was like a terrier at stroke and would fight to the last inch.

St Dunstan’s nurses used to come down from Regents Park bringing with them blind ex-servicemen to row. The nurses used to call out to them to get the timing of the stroke. I remember a huge Canadian jumping one of our boat stools while the nurse held his hands, both his artificial eyes fell out. He jokingly bemoaned the fact that he couldn’t see. It was so terribly sad to see these sightless young men, although they made light of their condition, and the nurses were wonderful.

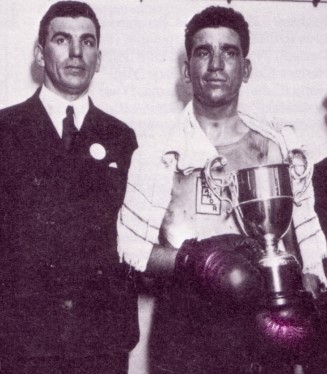

The Eton Mission had their own boathouse at Old Ford. They included in their membership the Mallin brothers who also rowed for Eton Manor BC. Harry was five times middleweight boxing champion, won two Olympic titles and was never beaten. His brother Fred won five middleweight titles – ten ABA titles between them in succession. Harry had plenty of offers to turn professional but was chief boxing instructor at Peel house, training young policemen and having the rank of sergeant.

The Mallin brothers knew that part of their boxing success came from rowing, which gives you great stamina.

After war Gladstone Warwick had a great senior pair in Charles Macbeth and Bill Hales. Bill was a 6-feet 2-inch blacksmith. ARA regattas had no coxed fours or pairs at this time, but there was no coxless rowing on the Lea owing to the large amount of traffic on the river. Charlie and Bill were members of a coxed four who won a race in Belgium just before the War and never had a chance to go for the Olympics. Charlie was a great stroke.

HRR and NARA

The first Henley regatta after the War had substitute trophies, the King’s Cup for eights. [Henley Peace Regatta, run by the Stewards]. A crew was formed from men on demob leave, including two from ARA clubs but entered as the NARA Service Men’s Crew. Their entry was refused. A round robin was got up with a large number of signatures and sent to the palace. The King’s equerry replied that his Majesty was very sorry, but as the regatta was run under Henley rules there was nothing he could do. The irony was that the sculls were won by D’Arcy Hadfield, a New Zealander who was a blacksmith, and the Aussies included several men who were artisans. It was a very snobbish decision.

From that day until 1937 no member of the royal family attended HRR. When George VI came to the throne a request was sent to the palace asking if a member of the royal family could attend. The reply came that his Majesty was very sorry but it was always his father’s wish that he must never attend a function when only one class of his people was represented. [The Australian eight for the 1936 Berlin Olympics was from the New South Wales Police and was refused entry by the Stewards – Chris Dodd] The rule was changed after the War and clubs like Poplar Blackwall and Tideway Scullers began to compete at Henley.

Professionals, Radleys and Clubs

My families were the mainstay of the Lea Bridge Club. My father was a fine powerful oarsman and sculler, and we all tried to emulate him. We were quite successful as a four with Dad, my two brothers Wally and Sid and myself and George [Clive Radley’s father] steering.

Borough of Hackney Regatta had races for professionals and amateurs. Other regattas were Putney Town, Hammersmith Borough, and Strand on the Green, Richmond Town, Bourne End, Reading Tradesmen, Oxford Watermen and Barnes. The rowing clubs included Putney Town, Sons of the Thames, Hammersmith, Barnes Bridge, Lea Bridge United, Staines Town, Henley United, Oxford Watermen and Parkside RC.

The Phelps family were the mainstay of Putney Town: Harry, Ted, Tom, Dick, Jack and Bill, the sons of Charlie Phelps, were all great scullers and watermen. Except for Bill, they were all Doggett’s winners including their father Charlie. They were all Queens’ watermen. Tom had the honour of being on the bow of the launch carrying Churchill’s coffin; Tom was boatman to London RC, Dick to Thames, young Jack was Winchester College boatman, Bill was at London University. They were gentlemen of the river in every sense of the word. Their cousins, Ted and Eric Phelps, were sons of Bossie – probably the finest rowing and sculling coach we’ve had although he was never allowed to coach crews officially, being a professional. Bossie Phelps ran a sculling school at Putney, and his sons Ted and Eric would be sculling all day with leading amateurs. Ted became world professional sculling champion, his brother Eric was the last British professional champion. Ted went to Brazil to coach and Eric went to Germany to coach, and was interned during the War.

Sons of The Thames had a fine crew just after the 1914-18 War – top crew for a few years: Bill and Fred Pearce, Fred Donovan, a heavyweight boxer, who left our club to join the Sons, and a member of the Cobb family, another great waterside family.

Barnes Bridge included the Barry family, Ernest Barry was world professional champion before and just after the 1914-18 War, he was probably the greatest sculler of all time. He had a perfect technique, his boat never stopped running between strokes, he would be moving just as quick at the finish as at the start. Ernie was also a great athlete.

During the war they formed the Sportsmen’s Battalion which included athletes, boxers, footballers, and Ernie could outrun the lot. When he retired, he was followed by his nephew Bert Barry as world champion. Bert lost the title to Ted Phelps who lost it to Bob Pearce, the Australian Olympic champion [who had turned professional]. The race was held in Canada on a lake over a triangular course of three miles with two turns round the buoys, on a lake where the water was dead. The reason was that the course could be enclosed so that an admission charge could be made. Ernie Barry was upset about this as it was not a championship course as the Putney to Mortlake and Parramatta courses were (memorial to Searle at the finish). Ted Phelps admitted that his arms tied up badly in the dead water – he was born and bred on the Tideway with its 4.25 miles of varying water and lively currents. To see Ted Phelps sculling through bad water was a sight to be remembered.

Barnes Bridge had a great crew with Ernie Barry, Bert Barry and Bill Coles, who retired after one season to be replaced by Lou Barry (2), Bill Peters (bow).

Pearce was big tough man without the finesse necessary to negotiate the Putney to Mortlake course on the top of the tide [He ranked as an amateur in Australia but a professional in Canada where he was in the employ of Dewars]. Ernie Barry was a tug captain, and when he rowed a championship race all the tugs and barges managed to get there to watch, so the water was always in turmoil, conditions which Ernie gloried in. Like Ted Phelps he had such light hands, I watched Ted winning the Putney Coat and Badge on a rough day. He hit a large wave, lost control of his right hand and scull, knocked it forward and caught it just before entry for the next stroke, all in the same movement. Ted was challenged for the British championship by Lou Barry. Lou won and then lost it to Ted’s brother Eric, another brilliant sculler.

After World War II the rules were changed to allow waterside men to row as amateurs. Some were reinstated and professional rowing died a quick death, along with the prejudice against professionals.

All our great pros had to do their coaching abroad, Ted Phelps in Brazil, Lou Barry in Italy, Ernie Barry in Denmark and Tom Sullivan (NZ) in Germany. Eric Phelps ‘helped if not coached’ that marvellous couple Jack Beresford and Dick Southwood, sitting in if one was not able to train, for the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Eric Phelps was coaching in Germany when the War broke out and interned.

A note about the Author

After World War II, Laurie worked at Pengwern boat club as boatman and in 1955 became boatman/waterman at Pangbourne College where he stayed until he retired in 1974. He played in a key role in the college’s success in rowing and met the Queen and Prince Phillip at the college boathouse.

Tributes from the Old Pangbournian Society Web Site:

Julian Coles (59-63), stroke of the winning 1963 Princess Elizabeth cup-winning crew at Henley wrote:

“Laurie was a real craftsman and I remember some of his repairs. I would rub my hand over a check he had fixed and marvel at how smooth the finish was. We were very fortunate to have him and certainly the boat was fast enough to win in ’63.”

Rob Green (57-62), Captain of Boats in 1962, wrote:

I only knew him as Mr Radley, and had huge respect for him. Softly spoken, he exuded an aura of quiet strength, reliability and practical competence. I remember being almost mesmerised by his beautifully smooth oarsman technique as he coached individual crew members in the old tethered punt on the riverbank. In short, he was a major asset to the Boat Club.”

Wonderful reading. Made my heart sing.

I have a somewhat sketchy recollection of a connection between Radley’s and the Clove Club. The Clove Club was the old-boys association of the Grocers Company Grammar School, which became Hackney Downs Secondary School when taken over by the LCC. I was very young during the later nineteen-thirties, but my elder brothers, one in particular, rowed on the Lea regularly, using boats from Radley’s boat-house. I still remember the tea-room, being bought an ice-cream cornet there by my elder brother Arthur, and being told never to reveal that, at the back of the tea-room, was a “secret” hand-operated fruit machine, frequently played by clients.

Hi Ronnie, I was told by my old coach that HDS in earlier decades had a rowing club.

I rowed for HDS in the 70’s and so did my brother Orhan.

I won J16 single sculls for HDS in 1976 at the national championships of GB

My brother won in the following years 77 and 78. He still rows at Lea rowing club.

Do you have any more information on rowing at Hackney downs?

Is there any history of Pengwern Boat House from about 1909,until 1922. Our grandfather Francis Edward Gale was the resident boat builder at that time. Please answer on tychi@ii.net.net au. Thankyou help if you can