12 January 2026

By Chris Morrell

The article writer, Chris Morrell MBE, received the Lifetime Achievement Award from British Rowing in December 2025. Morrell has 50 years of service to the Windsor Boys’ School Boat Club. He was awarded the Member of the Order of the British Empire in 2011 for his services to youth sport and education. Here he writes about his father Charles Morrell Morrell and Jack Beresford, both being members of Thames Rowing Club.

Tim Koch’s recent Hear the Boat Sing articles about the Beresford family photographic archive provide fascinating visual insights into the life and rowing times of Jack Beresford which prompted me to review my father’s association with the Beresfords.

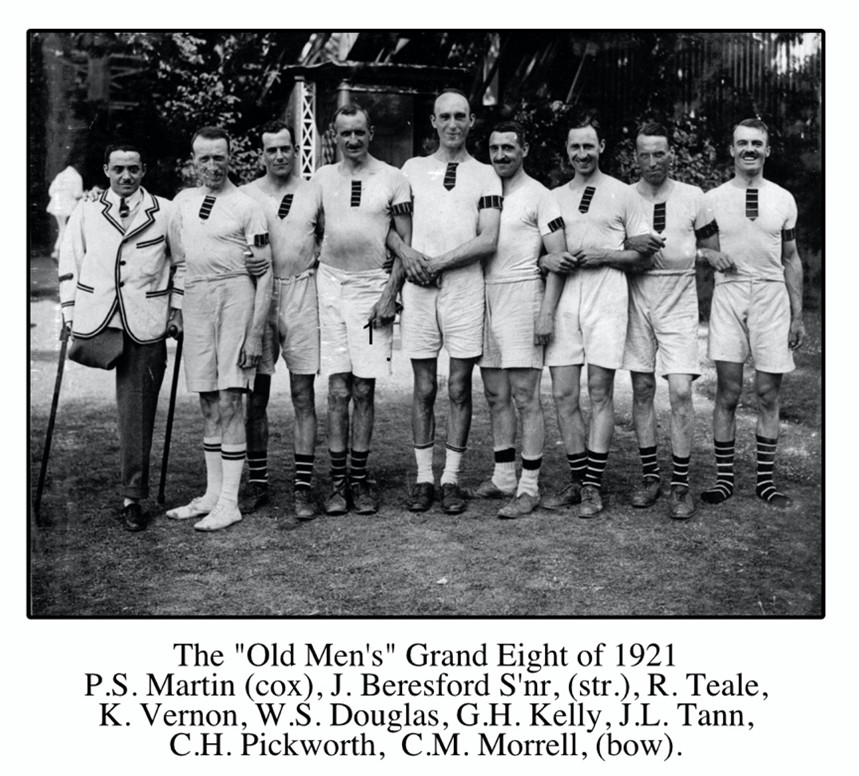

I was delighted when HTBS included my resumé of my father Charles Morrell Morrell’s (CMM) life in April 2024. Charles was a lifelong member of Thames Rowing Club (TRC) from 1912 until his early death at the age of 60 in 1949. He knew the Beresford family well, having rowed in the 1920 Thames RC’s Grand eight with Jack’s father Julius Beresford, commonly known as “Berry.” This crew was called the “Old Men’s” eight; Berry, at stroke, was in his early fifties whilst Charles, at bow, was a comparative youth at a mere thirty-one! Also in the crew was Karl “Bean” Vernon, another notable veteran, who, with Berry, had won the silver medal in the GB coxed four at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics. Subsequently CMM was rowing team manager at two of the five Olympic Games in which Jack Beresford successfully represented Great Britain.

In his book Hear the Boat Sing – The History of Thames Rowing Club and Tideway Rowing, Geoffrey Page describes the 1920 TRC Grand Challenge Cup race against New College, Oxford, at Henley Royal Regatta:

The Thames veterans were again put in for the Grand and still included Berry (Julius Beresford), now fifty-three, Bean Vernon, Duggie Douglas, George Kelly, and Laurie Tan, all of pre-war vintage, though Bruce Logan had finally retired. Also in the crew at bow was Charles Morrell (now aged thirty-two) who had been a prisoner of war in Holland. Not too much was expected of them, but they put up a remarkable performance against New College in their heat coming from three-quarter length at the half Mile to pull back to within a quarter length at the Mile, but this time age proved too much and Berry’s final spurt could not prevent the college drawing away to win by three-quarter length.

It was in the same year that Jack Beresford started his Olympic career in Antwerp, Belgium, winning a silver medal in the single sculls. He narrowly lost to the legendary Irish-American sculler, Jack B Kelly. The race is described by Geoffrey Page:

The final lived up to the occasion, there being very little in it throughout. Beresford had a slight lead at the end of one minute and held it until the last 100 metres. Neither man cracked, but the 6-foot 5 inch American, weighing over 14 stone against Beresford’s 11st 4lb, and at thirty years of age Beresford’s senior by ten years, proved to have that bit of extra strength and won by one second.

Kelly’s 1920 entry into the Diamonds at Henley had been rejected, falling foul of the rules regarding amateurism and manual labour, Kelly having previously been an apprentice bricklayer. His US club, Vesper BC, had also been banned from Henley after 1905 infringements of the amateur status of their regatta entry. The Vesper ban was removed soon afterwards by the Stewards, but Kelly never raced at the Royal Regatta.

CMM was a frequent contributor to the Java Gazette as part of his post-war job as General Secretary to the British Chamber of Commerce for the Netherlands East Indies. An article titled “Some Rambling Rowing Reminiscences” dated November 1934 included the following from (possibly) 1924:

A very amusing incident happened at Bruges Regatta in which Jack Beresford was sculling. His chief opponent was an enormously strong Italian who looked like a professional strong man: Jack, although beautifully built only weighed 11½ stone and looked almost frail compared with his gigantic adversary. The spokesman of the Italians present (who were quite certain that their champion could not fail to win) said to me ‘your signor Beresford he verra good – but our man he is so big and strong he pulla da boat and winna da race!’. Unfortunately for him the Italian was completely outclassed by Jack who ‘lost’ him in ten strokes and paddled gently to the finish many lengths ahead.

In the same article CMM refers to Jack’s sense of sportsmanship:

It is interesting to remember that in 1921 it was Jack Beresford who stopped sculling and waited for his Dutch opponent Eyken, in the final of the Diamonds when the latter had been brought almost to a standstill through fouling the booms. Jack’s almost quintessentially sporting action won him immortal fame in Holland. He received innumerable letters of appreciation from Dutch people of all classes including one form the organist of a world -famous cathedral.

Page described the incident:

[…] Beresford again reached the Diamonds final, where he met the Dutch sculler, Frits Eyken whom he had beaten at Antwerp. Beresford destroyed his chances through an exceptional gesture of sportsmanship. The scullers were level at the top of the Island when Eyken hit the booms. Beresford stopped until the Dutchman was straight again and led by only ½ length at the first two signals. At Fawley, they were level, but Eyken lasted the better, to cause one of the major upsets of the regatta in winning by 1½ lengths, but Jack had at least put the word ‘gentleman’ back with ‘amateur’.

The Olympic regatta at Paris in 1924 (the “Chariots of Fire” Games) was, by all accounts, a poorly organised affair. The course on the Seine was frequently chopped up by leisure craft and passenger boats and the umpires’ launch was a punt driven by an aeroplane propeller which effectively drowned out all possibility of hearing anything onboard or outside the boat! This craft used to go around the crews waiting on the start, creating a persistent wash. Beresford had been selected in the single at the trial for GB along with the Thames eight. Beresford avenged his narrow defeat in 1920 winning the four-boat final by five seconds, despite having to qualify through the repechâge round. The eight, (stroked by Ian Fairbairn, son of legendary TRC coach Steve), had a poor final, finishing fourth. The other GB entry, a coxless four from Third Trinity BC, Cambridge and Eton Vikings, won its final.

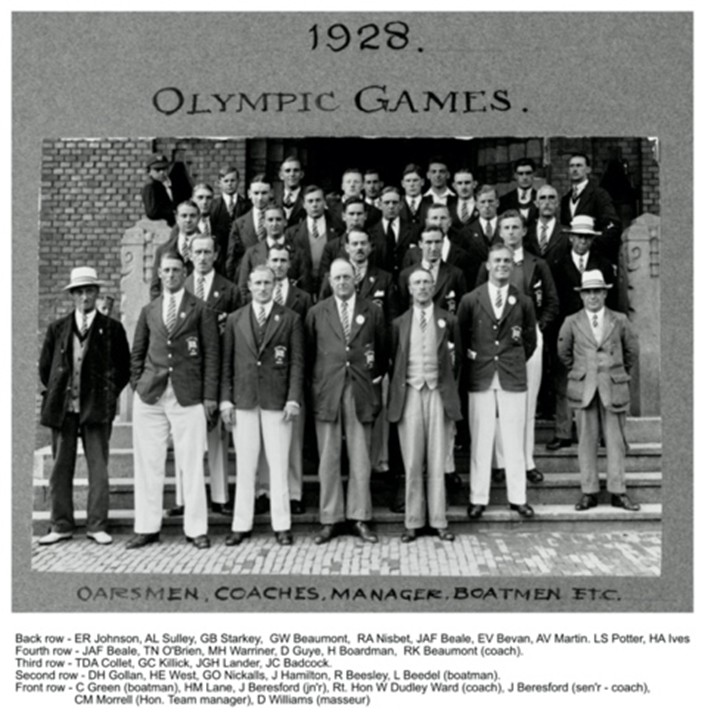

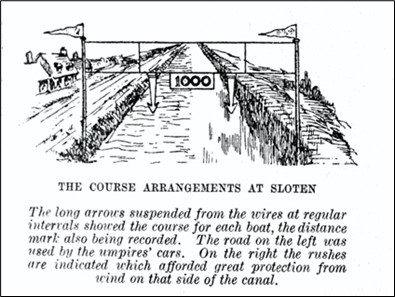

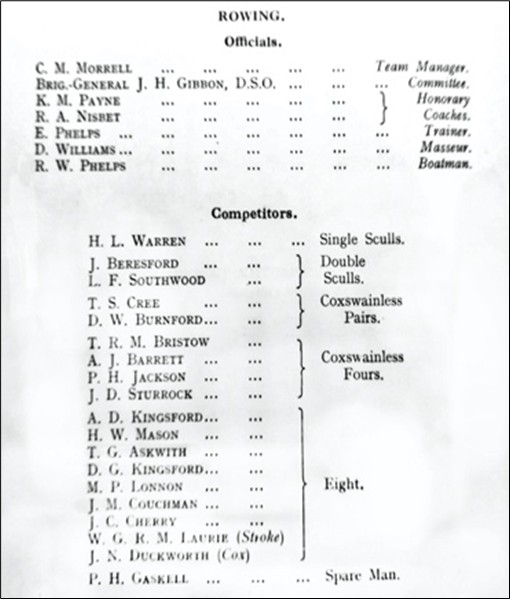

CMM’s next ‘formal’ association with the Beresford family was at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics when he was appointed rowing team manager and Jack was rowing at two in the Thames eight representing Great Britain. Charles’s appointment was probably a consequence of his fluency in Dutch, learned whilst interned in Holland during the Great War, his knowledge of French and his rowing pedigree. The Olympic regatta was held on a reed-lined canal at Sloten, a few miles outside Amsterdam.

According to the report in the 1929 British Rowing Almanack the two-lane course was considered to be fair unless there was a crosswind. In the first round of the Eights event GB raced Italy, the reigning European champions, winning by a mere ½ length. The Polish eight was next dispatched by 6 lengths. Then the GB crew met Germany in the semi-final. This was the first time that Germany had been allowed to compete since the end of the Great War. Hamilton, the GB stroke, remembered this as the most dramatic heat of the regatta; “They led us near the finish and when we spurted and drew level they cracked and did not finish the course.”

The eights final was described in the Almanack as follows:

The final brought together two of the finest crews in the rowing world. The spectators looked forward to a thrilling encounter and were in no wise disappointed. Both crews went off at a very high-rate, Hamilton putting in 42 to the Americans 44 in the full minute. The boats hung together, and not until a quarter of the course had been completed did the Americans show half a length ahead. At half way they held a length, though Thames were gaining on them. From the 1,000 metre mark the Americans spurted no less than four times. Four times their coxswain rattled imperatively with the side-plates against the hull for the last ounce to be put in, but in spite of all the efforts his men put forth, Thames came up on them. The last five hundred yards saw both crews beginning a desperate final burst, Hamilton putting in 40 to his opponents 42, and it seemed as though the Englishmen might just snatch victory on the post. They only just failed, after a long and splendid spurt. The excitement was overpowering, but the Americans kept it going and shot home a bare half-length to the good in 6 min. 3 sec. The race came last on the programme and was a fitting wind-up to as fine an Olympic regatta as has ever been witnessed.

In the Almanack’s ‘Review of the Season’ CMM was commended for his efforts as the GB Team Manager:

Mr C Morrell, who went over as manager of the British rowing section and who speaks Dutch like a native, was of immense assistance to all countries. His efforts were greatly appreciated by our crews and the International Committee, who at the end of each day’s racing arranged the details for the following day. His luck was exceptionally good when matters cropped up in which all parties were not quite of accord, especially as regards the repechage races.

This was the first Olympic regatta where a limited repêchage system was introduced. Jack Beresford commented on the far from ideal logistical travel arrangements:

Once again, the British chances were jeopardised by the situation of the hotel, miles from the course; consequently, a hair-raising motor coach or taxi run had to be undertaken four times a day. Travelling a distance under the best of conditions is to be deprecated, and on the existing, winding narrow paved roads, it had to be experienced to be appreciated.

In the 1928 edition of the Netherlands Indies Review, forerunner of the Java Gazette, CMM wrote:

The Games of the Ninth Olympiad at Amsterdam have been concluded. Those fortunate enough to be present witnessed a bewildering and inspiring galaxy of talent and courageous prowess, gathered from almost every corner of the civilised world, that only the call of the Olympic Games could cause to be assembled in one town.

The Games were admirably organised and, except for one or two minor incidents, were conducted by both competitors and officials in a spirit of sportsmanship which reflects great credit upon all concerned. In fact, it does not seem an exaggeration to state that, with very few exceptions, the competitors showed themselves to be sportsmen according to the poet’s definition:

‘And when the Great Scorer comes,

To write against your name,

He’ll ask not if you won or lost,

But how you played the game.’ *

The Dutch public showed itself to be as sporting as the competitors and applauded individual performances on their merits alone.

It has been alleged that international competition breeds quarrels and bitterness of feeling and for that reason ought to be abolished. We do not believe that to be correct. On the contrary we believe that the Olympic Games constitutes an opportunity for individuals representing the youth of the countries of the world to come together in a spirit of sportsmanship, good fellowship and understanding of the ‘other fellow’s point of view’ without which the economic and intellectual development of the world is impossible.”

*[Quote attributed to Grantland Rice, 20th Century US sports journalist.]

In 1930 CMM was appointed as team manager for the England rowing team at the inaugural Empire Games, which evolved into the Commonwealth Games, at Hamilton in Ontario, Canada. Twelve countries competed in these Games with England leading the medal table, amassing 25 gold, 22 silver and 13 bronze. The rowing team won two golds, in the eights and coxless fours. In the singles, Jack Beresford won silver and Fred Bradley won bronze. Jack Beresford wrote an article for Rowing magazine reviewing the Games:

In 1930 a group of keen sportsmen and great believers in the Empire put their heads together way out in Hamilton, Ontario and this resulted in the inauguration of the first British Empire Games. To the people of Hamilton, the Government and peoples of these islands owe a tremendous debt, for these Games are without question, of untold value in cementing the friendship between the Mother Country, the Dominions and Colonies.

In 1930 the London Rowing Club eight, winners of the Grand, beat a very tough New Zealand eight by half a length and thus became the first Empire champions. Bob Pearce**, the famous Australian, won the Empire Sculls, with Jack Beresford second, Fred Bradley, elder brother of the present stroke, third and Joe Wright of Canada last.”

**[Pearce won the gold medal in the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics and later became professional sculling champion of the world.]

CMM retells the story of the social exploits of the eight’s cox whilst on the Canadian Pacific steamer transporting the English athletes to Canada:

The London Rowing Club’s cox’ was a well-known Cambridge ‘blue’ and one of the most amusing people I have ever met; he was killed in a military flying accident comparatively recently and the world is poorer by one gallant little sportsman. The steamer also carried a British Medical Mission which was to attend a conference in Canada; one of its members was a distinguished titled physician who was accompanied by his wife. The London cox’ was naturally not in training like the oarsmen and on the evening of a dance on board he ‘gazed upon the vintage when ’twas crimson’; during the dance he walked quite steadily up to the aforesaid distinguished lady and said to her – ‘have a dance girlie?’; far from being annoyed she and her husband were apparently very amused; she danced with him, and I believe they became great friends.

Work commitments in the Netherlands East Indies prevented CMM’s involvement in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics where Jack Beresford was in the GB coxless four which had a resounding 2½ length victory over Germany, Italy and the USA. This would be his second Olympic gold, adding to the two silver medals won at Antwerp and Amsterdam.

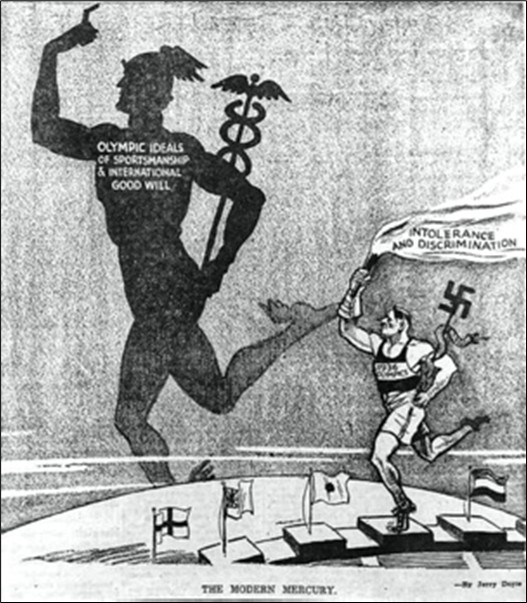

In 1936 CMM attended the British Olympic Association in 1936 prior to the Olympic Games to be held in Berlin. Present were many notable Olympians, including Harold Abrahams (100m gold in Paris), Lord Burghley (David Cecil, 400m hurdles gold in Amsterdam and in LA) and New Zealander Jack Lovelock (1500m gold in LA, setting a new world record). Under the title ‘Olympic Jottings’ [Java Gazette, May 1936] CMM commented:

Many excellent speeches were made, amongst the most striking of which was in my opinion that of Lord Burghley, who with emphatic eloquence appealed to the Press not to lose their sense of proportion. I am sure that Lord Burghley had in his mind the regrettable tendency amongst certain journalists to manufacture a sensational story at all costs, which as far as the Olympic Games are concerned might lead to grossly exaggerated reports of trivial incidents. Such distortion could well be inimical to the spirit of the Olympic Games which is so important to today’s troubled world, namely the fostering of peace and goodwill amongst nations.

From the excellent speeches by Sir Robert Horne, Lord Portal, Sir Thomas Inskip and not least Dr Lewald [German Olympic President] it is evident that they too rightly attach great importance to the Olympic Games in assisting the world in this sense.

Perhaps Beresford’s greatest Olympic triumph was at Berlin in 1936 where he partnered Leslie Frank “Dick” Southwood (both TRC members) in the double sculls. Unusually for the time they had been training as a crew for several months prior to the Games.

Jack, in recognition of his past Olympic successes, had been given the honour of being the GB flag bearer at the opening ceremony. The team gave Hitler a smart ‘eyes right’ as they marched bareheaded past the Chancellor’s elevated podium in front of 100,000 wildly excited spectators, rather than the prescribed Nazi salute! Infamously, in 1938, the England football team playing against Germany acknowledged Herr Hitler with the statutory raised right arm!

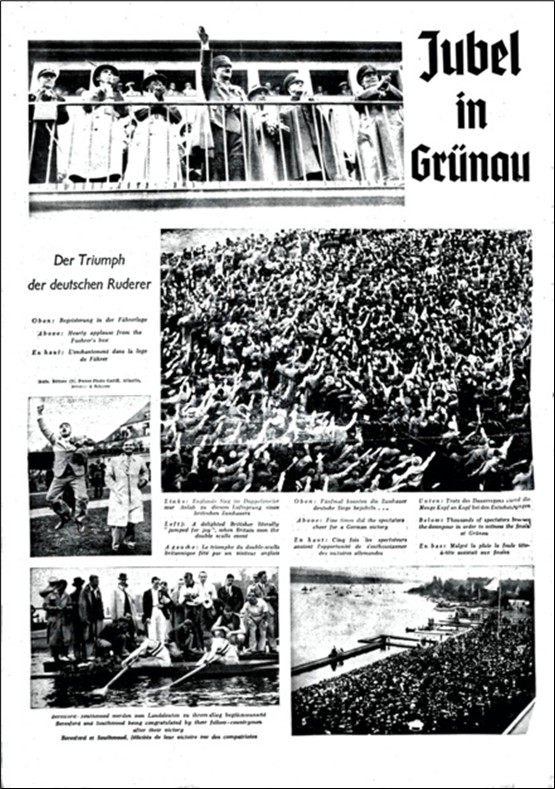

At the regatta on the Langer See in Grünau, Beresford and Southwood lost to the fancied German double of Willi Kaidel and Joachim Pirsch in the first round and were obliged to race in the repechâge round. To make a statement the GB double went flat out from the start and established a large lead such that they were able to paddle to the finish line. They were using a brand-new lightweight boat for the first time which arrived just in time for the regatta, having been ‘misdirected’ on its arrival in Hamburg. According to Beresford’s son, John, on the night before the finals, there was a continual disturbance outside the team hotel in an organised attempt to disturb the GB team’s sleep.

The doubles final was the sixth race on the regatta programme; the Germans having triumphed in the preceding five. (The GB coxless four took the silver medal, inevitably behind the German crew). Using the observation that the Germans had been ‘jumping the start,’ it having been noticed that the starter’s view of the crews was obscured by the large megaphone being used, especially those in lanes three and four, the GB double did likewise. Despite this, Beresford and Southwood trailed the German crew by 1½ lengths at halfway with the remainder of the field, Poland, France, Australia and the US, trailing. Believing that the Germans were good only to 1800m, the GB double gradually reduced the deficit until they were level with only 200m to go.

Author and sports journalist Hylton Cleaver, in his History of Rowing, remembered the race:

At half-way our men really began laying it on. They were belting every stroke as hard and as long as they could, and I can see them now as they approached the enclosures, where I was standing on tip-toe scarcely able to shout for the lump in my throat.

From 1,000 metres it took them more than 800 more before, by their utmost efforts, they got level at last, and at this point Tom Sullivan***, with field glasses clapped to his eyes, snatched off the cap of the Berliner Ruder Club, which he wore, to flourish it high in the air and bellow above the roar of the crowd, as if his heart was bursting: ‘The Englishmen have got them! The Englishmen to win, for 1,000 marks!

***[Tom Sullivan (1868-1949) born in New Zealand. NZ and English sculling champion. He coached crews at Berlin Ruder Klub from 1913 and coached the German coxed four to gold at Los Angeles in 1932.]

In the remainder of the race the two crews were sculling stroke for stroke until the Germans cracked and stopped rowing directly in front of Hitler’s box allowing Beresford and Southwood to cross the line 2 ½ to the good. Beresford claimed that “… it was the sweetest race he ever rowed in.” Apparently, Hitler was so infuriated at his perceived ‘failure’ of the German crew that he stormed out of the stand. He was to be further stressed when the University of Washington eight won the last race of the regatta for the US with the German crew third, a story memorably described by Dan Brown in The Boys in the Boat.

In his article “Olympic Jottings” (Java Gazette, September 1936), CMM wrote:

One of the happiest parties to go to the Olympic Games was the British Rowing team, drawn from Jesus Cambridge, Leander, Thames and Trinity Hall. They showed that they knew how to win – and lose.

Beresford and Southwood’s (Thames RC) glorious victory in the Double Sculls is a classic example of what can be achieved by a British crew intensively trained for the Games. They had been together for about ten months and were probably fitter and tougher than any other competitor in the Olympic Regatta, in spite of the fact that their respective ages are thirty-seven and thirty.

To sum up, the Germans are to be congratulated on the faultlessly efficient manner in which they conducted the Games and for their successes in all branches thereof. And now for Tokyo.

With the onset of the Second World War in 1939, the Tokyo Games never took place, depriving Beresford of the opportunity to compete in his sixth Games. It wasn’t until 1948 that the Olympic movement was resurrected in London.

An outcome of Beresford and Southwood’s 1936 Olympic victory, however, was the institution of a Double Sculls event by the Henley Stewards at the 1939 Centenary Regatta. With eight entries in the event the 1936 Olympic victors reached the final to meet the Italian double of Scherli and Broschi. Page described the final of the event:

There was a strong headwind and Thames were giving away a substantial amount of weight and years. Thames took ½ length lead in 20 seconds but as they came out of the shelter of the Island, they almost lost their lead. The Italians were just in front at Fawley and spurted to increase their lead to a third of a length at the ¾ Mile, but when the Italians dropped their rate again, Thames came up and went ahead by a few feet. Once more their opponents put in a dramatic spurt to gain ½ length by the Mile, and once again Thames came back, only for the Italians to make yet another effort and draw ahead. At last signal, it looked all over. However, Southwood worked the rate up and up, and stroke by stroke Thames closed up to catch the Italians on the line for a dead heat.

The sequel to this epic race was, with both crews slumped exhausted in the boat tent, Beresford casually strolled over to the Italian crew and suggested a re-row in half an hour. The offer was politely declined, and honours remained even! In 1946 the HRR Stewards instituted the Double Sculls Challenge Cup.

As a postscript to the above my mother, Elvira who survived Charles by over fifty years until her death in 2008, used to tell me that Jack and Charles were in ‘competition’ as to who could get their child enrolled as the youngest TRC member first! I was born on 1st May 1946; I wonder if John B. beat me to that honour?

Thank you for more fascinating information about Dad.