7 January 2026

By Edward H. Jones

In Part I, Edward H. Jones introduced HTBS readers to the Shoe-wae-cae-mette rowing crew (the “Shoes”). In Part II, the author describes the crew’s performance on the second day of the 1878 Henley Regatta and the subsequent fallout from their appearance.

Hurrah! the rowing “Shoes” (continued from Part I)

The second day at Henley

went poorly for the “Shoes.”

Their 2-seat had an illness

which caused their boat to lose.

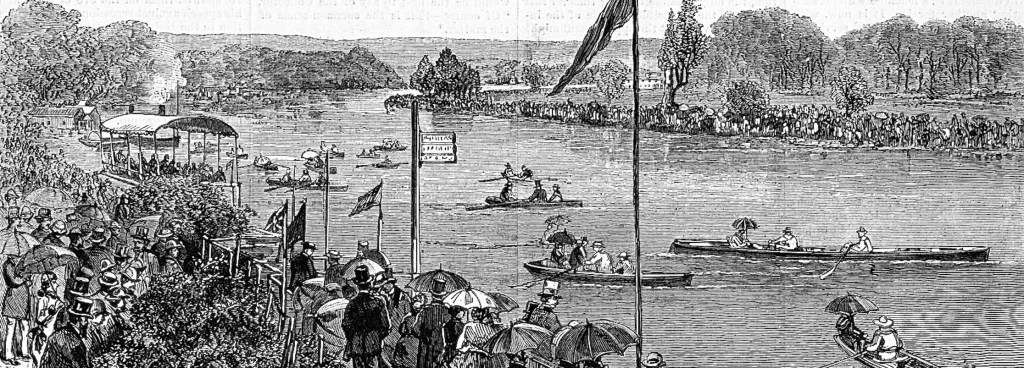

Henley never saw a lovelier day than yesterday, nor a more brilliant assemblage than that which gathered to witness this year’s regatta. The meadows on both sides of the Thames were filled with people, the bridge was blocked with drags (private coaches) and carriages, while the river swarmed with craft of every description. The gay dresses of the ladies and fancy rowing costumes of the college boatmen made the scene particularly charming and picturesque. There was a sprinkling of Americans, but their presence was scarcely noticeable in the large numbers of natives.

– Springfield (MA) Daily Republican, July 5, 1878, 8.

The second day at the 1878 Henley Regatta saw an estimated twenty- to thirty-thousand spectators gather along the banks of the Thames, in pleasure boats on the river, and on the stone-arched Henley Bridge. The second trial heat for the Stewards’ Challenge Cup was won by the London Rowing Club the previous day on July 4th. This earned them the right to compete against the “Shoes” on July 5th in the final heat for the Cup.

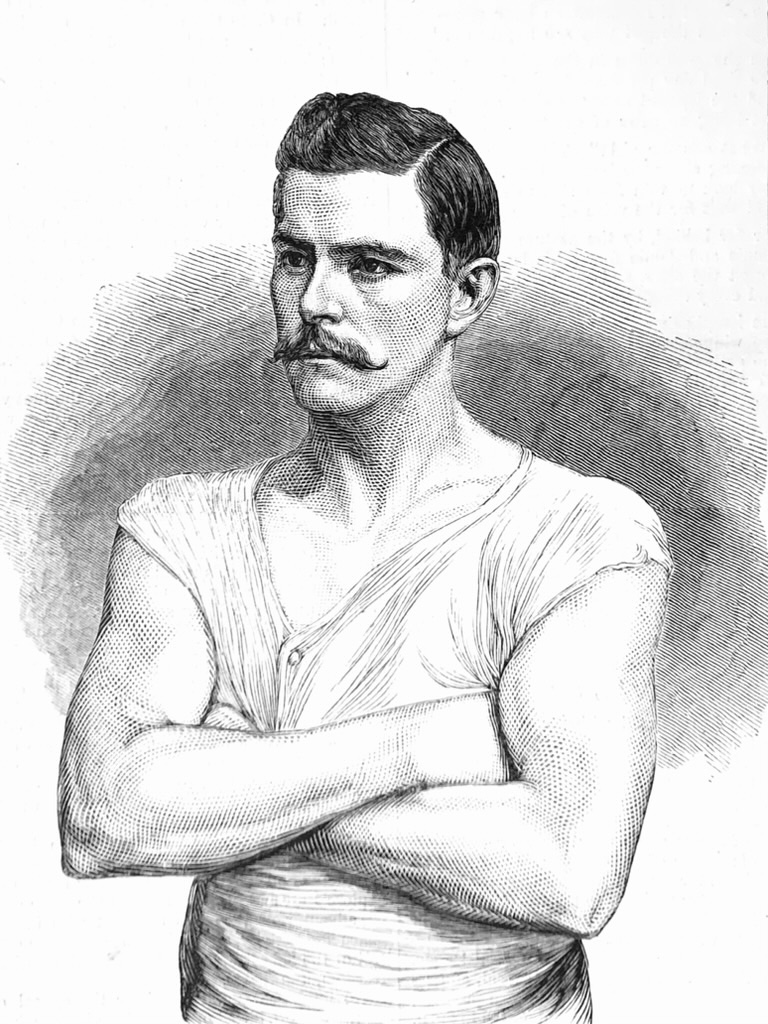

The bronzed cheeks and hardened muscles of the Michigan oarsmen are in marked contrast with the pale faces, white arms and more aristocratic appearance of the Englishmen, especially the college fours.

– History of Monroe County Michigan, 1890, 396.

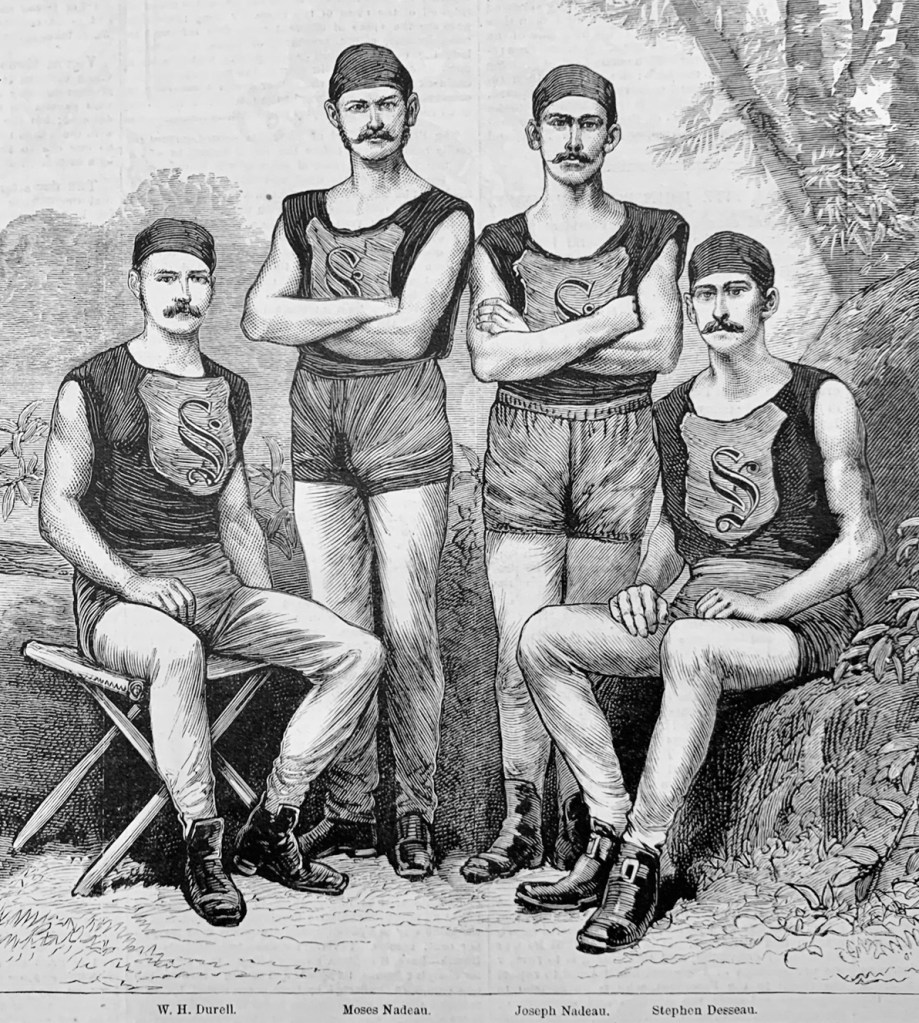

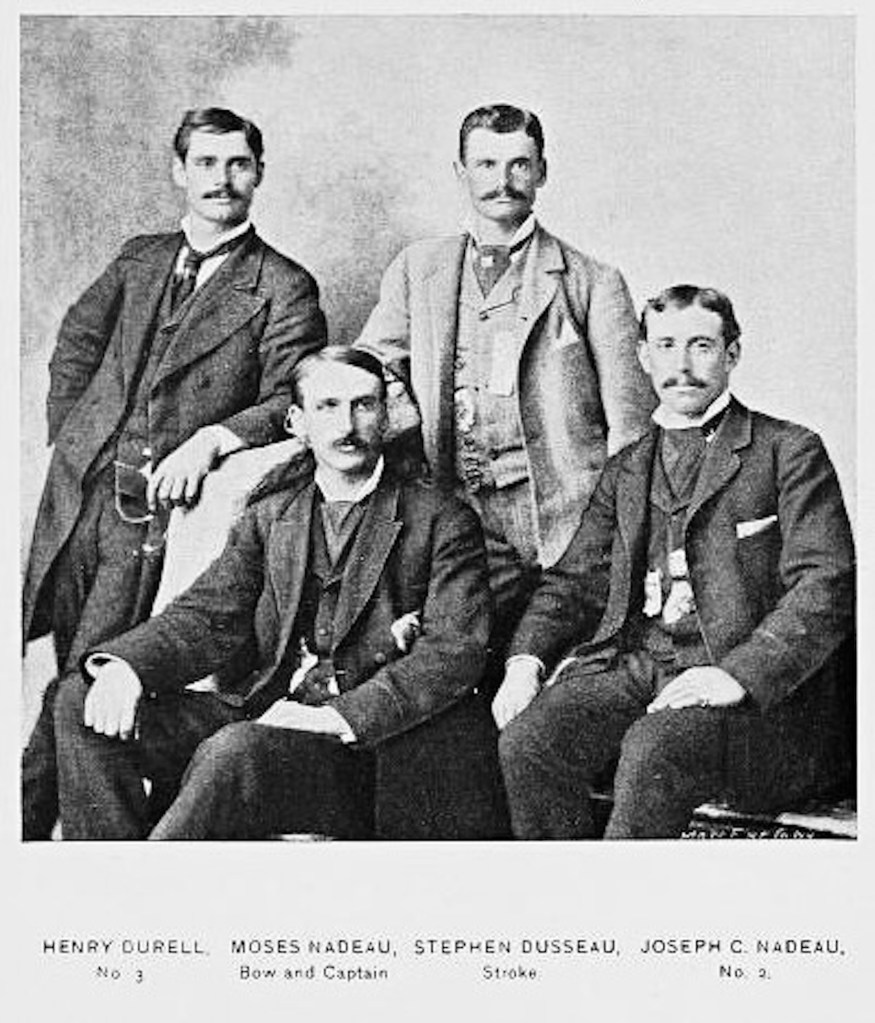

At the starting signal the “Shoes” went “off like a shot” rowing fifty strokes to the minute. Their plan was to keep as close as possible to the London crew up to the bend in the course and then draw upon “their own wonderful supply of endurance to row the others to pieces with one of their famous long-continued spurts.” They carried out this plan to the end of the first mile at the bend, keeping their bow tip withing five or six feet of that of the London boat. Both crews were rowing well when suddenly the London crew shot ahead in an astonishing manner, and it appeared that something was the matter in the “Shoes’” boat. After pausing a few seconds, the “Shoes” went on slowly with Moses Nadeau, Henry Durell, and Stephen Dusseau pulling the boat alone. Joseph Nadeau, Moses’ brother, was doubled up and began to vomit. He had been ill the night before from intestinal distress, and upon reaching the one-mile mark during the race he could not row any more, and the crew had to completely stop. The “Shoes” simply could not finish.

One source said that Nadeau had suffered from what it termed “sculler’s colic” without providing any details about the ailment. At first the “Shoes” accepted their defeat with nonchalance. They kept up their spirits before the crowd and even made light of losing the race, but once back at their quarters were said to have cried at their bitter disappointment. This wasn’t the first time Joseph Nadeau had taken sick prior to a race. In 1875, shortly before the Northwestern Amateur Rowing Association Regatta at Toledo, Ohio, Nadeau took ill and had to be replaced by a substitute. Fortunately, in that instance the Shoe crew plus the substitute overcame the disruption and won their race.

It is confidently claimed by [the “Shoes”] that they would have won but for Nadeau’s illness. There were some hints of foul play in the matter, but these were only based on the fact that one of the substitutes who accompanied the crew and one of their guests were similarly affected the same day.

– New York Daily Herald, August 1, 1878, 9.

Foul play was never proved.

Although the “Shoes” failed to finish, Harper’s Weekly nonetheless said that their “splendid rowing the day before was sufficient to establish their reputation as oarsmen even in the eyes of the English public.” However, the Sydney Mail weeks later was not quite as complementary:

There was a crew there, . . . hailing from America, called the “Shoe-wae-cae-mettes,” that astonished the natives not a little. They had the reputation of being the fastest amateur crew in America. They were referred to as half-horse, half-alligators. Their name was unpronounceable, their dress most fantastic, their stroke a short jerk, working 48 to 50 a minute. Their idea of starting was to obtain three or four lengths’ lead before the word “go” was given, and during the race they accompanied their stroke with hideous yells and screechings. Their place at the finish was a quarter of a mile astern. After the regatta it was ascertained that, whether half-horse or half-alligators, they were certainly not amateurs, either in the American or the English sense of the term.

– Sydney Mail (New South Wales), October 5, 1878, 540.

The Boston Post had a similar attack on the “Shoes’” first-day win:

The victory of the Shoe-wae-cae-mettes puts everything like decent rowing out of countenance. They have broken up all the nice rules of the business as effectively as Bonaparte revolutionized the accepted art of war.

– Boston Post, July 8, 1878, 1.

The New York Times, who just a few weeks earlier had heaped praises on the “Shoes,” now vilified the men from Monroe, Michigan, the day after their July 4th victory:

THE WICKED SHOE-WAE-CAE-METTES

The news from the Thames yesterday cast a gloom over our rowing men. They felt that the country had been disgraced by the revolting conduct of the Shoe-wae-cae-mettes. It is perfectly notorious both here and in England that these men don’t know how to row, but nevertheless, with an impudence that is really intolerable, they have beaten the rival crews in their first Henley heat so badly that the latter are said to have been virtually out of the race long before it was ended. Such an utter want of decency cannot but excite in every real oarsman feelings of loathing and indignation. . . . There is nothing that can compensate for want of style in rowing, and a good style can only be acquired by prolonged and earnest study.

Now, the Shoe-wae-cae-mettes have absolutely no style at all. . . . The faults of this ignorant and incompetent crew are legion. In fact, they are unquestionably the worst crew that was ever gathered together. . . . Their style is to the last degree ragged. The Englishmen who saw them practicing on the Thames were greatly amused at their ridiculous appearance. . . . As for training, they violated all the established rules. They ate what they pleased, and drank not only beer, but whisky. Last of all, they wore ragged flannel shirts, which were really quite disreputable, and which called out several remonstrances from the respectable British.

– New York Times, July 5, 1878, 4.

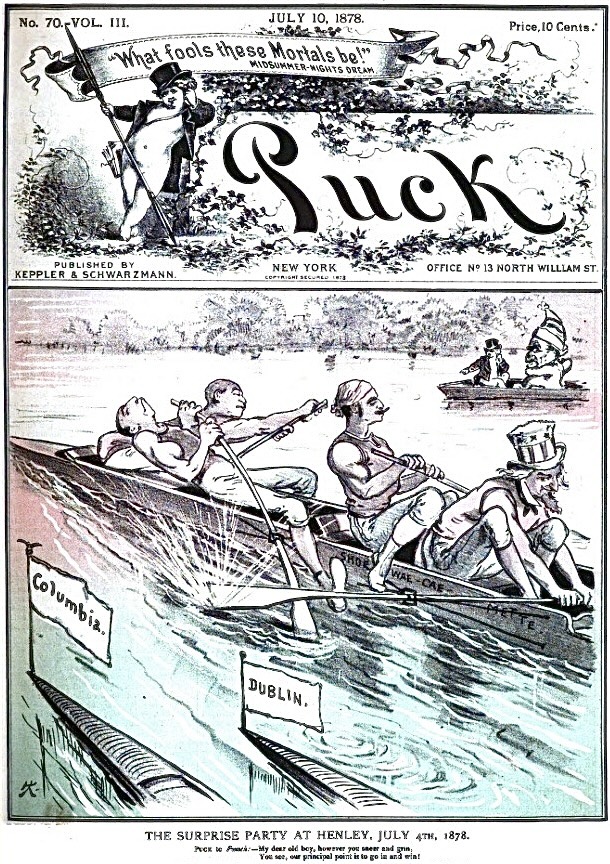

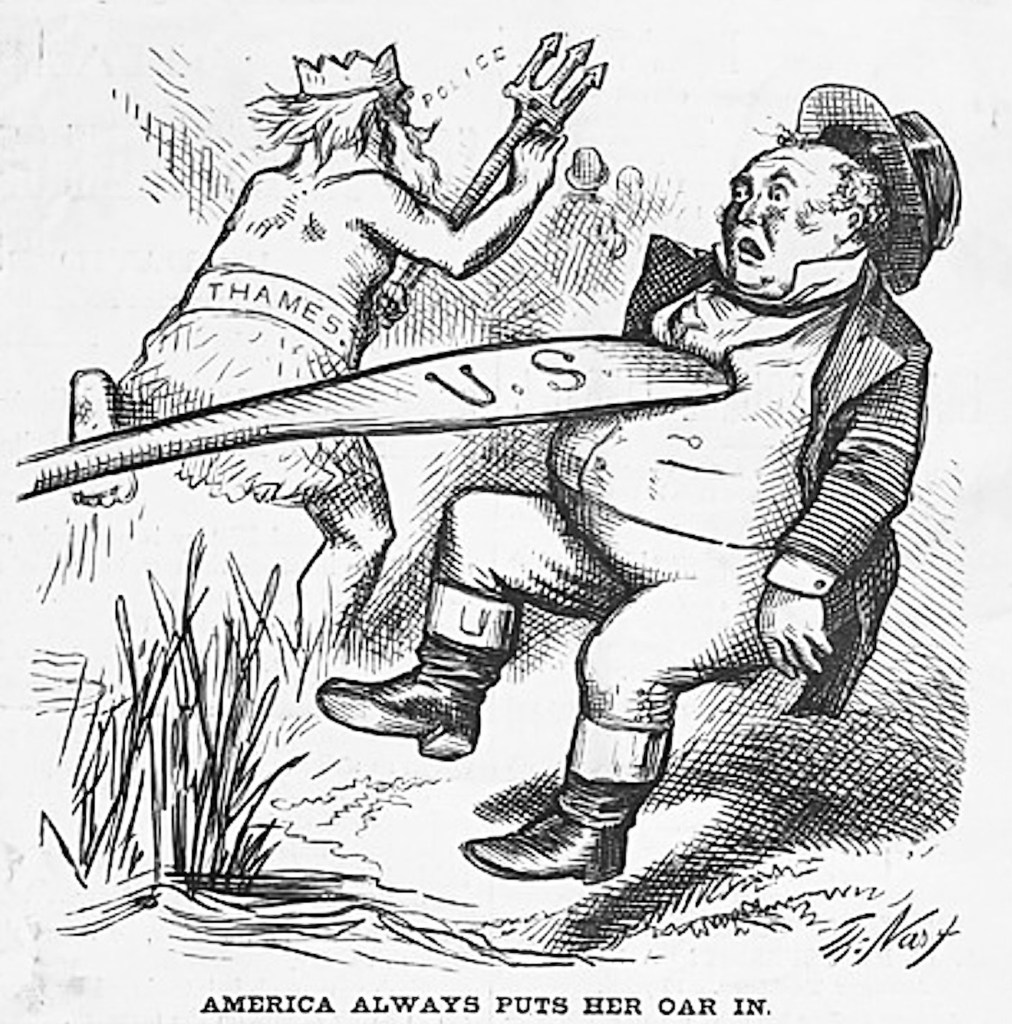

Six days after the “Shoes’” Fourth of July victory over Columbia and Dublin, the humor magazine Puck published a cartoon on its cover that appeared to illustrate the criticisms put forth by the New York Times in its article titled “The Wicked Shoe-Wae-Cae-Mettes.” Perhaps use of the word “Wicked” was a bit theatrical (pun intended), but the article also called the “Shoes” an “ignorant and incompetent” crew and “unquestionably the worst crew that was ever gathered together.” The article also slammed the “Shoes’” training methods noting that they violated all the established rules – “They ate what they pleased, and drank not only beer, but whisky.” The red- and green-tinged Puck cartoon shows a racing crew meant to represent the “Shoes” rowing a four-oared shell with “SHOE-WAE-CAE-METTE” inscribed on the hull. Uncle Sam is the stroke oar, unable to make a clean catch because of the outstretched leg of the 2-seat, who appears to be passed out, apparently in a drunken stupor. The 3-seat glibly smokes a cigarette, while the bow struggles with his oar after apparently “catching a crab.” Despite the “Shoes’” bumbling in the cartoon, they nonetheless are shown finishing ahead of Columbia and Dublin in what was the first heat of the Henley Stewards’ Challenge Cup race on the Fourth of July. Accordingly, the caption of the cartoon is “The Surprise Party at Henley, July 4th, 1878. Seated in a boat watching the race are Puck, the American magazine’s namesake and masthead figure depicted as a cherub-like character wearing only a top hat and coat, who is speaking to Punch, namesake of the British humor magazine personified by the slapstick (literally) puppet of Punch and Judy fame. Puck says to Punch: “My dear old boy, however you sneer and grin, – You see, our principal point is to go in and win!” which is exactly what the “Shoes” did, despite being ridiculed by the British rowing establishment and the press.

When this objectionable crew entered as the antagonists of skillful oarsmen, they certainly took a great liberty; but no one supposed they would carry their presumption so far as to win. This, however, is precisely what they have done, and there is a general and very justifiable opinion that their conduct was an outrage. They could not row, and yet they best crews who could row. They will probably grow bolder with impunity, and proceed to win more races, unless public sentiment and the Police interfere.

– New York Times, July 5, 1878, 4.

Following the appearance of the “Shoes” at Henley in 1878, as well as the appearances by other American oarsmen at that regatta, Harper’s Weekly published a second cartoonon July 27th (the first can be seen in Part I) hailing the audacity of the upstart American oarsmen competing at Henley. The cartoon, by Thomas Nast, shows an oar with “U.S.” printed on the blade representing the United States oarsmen, with the blade being shoved into the chest of a stunned John Bull, a national personification of England depicted by a gentleman of ample girth wearing a low top hat, coat and tails, and riding boots. In the background is the mythical Neptune ruling over the River Thames and calling for the police, perhaps so they can dispense with the conquering American rowers. The caption reads “America Always Puts Her Oar In” suggesting that America won’t hesitate to compete in a regatta, even across the Atlantic in England.

The worst of it is that this Shoe-wae-cae-mette victory will bring real rowing into disrepute. Men will say, what is the use of a finished style, a perfect boat, a careful training, when races can be won by crews who are totally deficient in these things? . . . If rowing is to be hereafter regarded as a delicate and difficult art, something must be done to stamp out the conduct of the Shoe-wae-cae-mettes with proper reprobation. They have struck a deadly blow at elegant and artistic rowing, and good oarsmen ought to refuse to recognize, and, above all, to row with, men who win races in violation of rules and precedents.

– New York Times, July 5, 1878, 4.

Hurrah! the rowing “Shoes” (cont.)

The Henley Stewards took a stand

for amateur ideals.

They banned the “Shoes” from coming back

with no chance for appeals.

The “Shoes” and George W. Lee returned to New York from London via the steamship Utopia on July 31st, and the “Shoes” arrived back home in Monroe on August 3rd. The Detroit Free Press reported that the “Shoes” were given an enthusiastic reception by their fellow citizens. Hundreds of people met them at the train, and they were escorted by the Monroe Cornet Band to the town square. Addresses of welcome and congratulation were made by prominent citizens, and appropriate responses were made by the “Shoes.” Friends of the crew were said to be planning to purchase for them a new racing shell to replace their old one which was ruined on the trip back from England.

HENLEY PROSPECTS . . . The professional “amateurs” of America, such as Lee the sculler, and the Shoe-wae-cae-mette crew, are not to be admitted to the entry this year. It was a mistake to allow them to do so last season; for they were no more amateurs than any of the artisan crews which row as “tradesmen’s” clubs in this country.

– Pall Mall Gazette (London), May 30, 1879, 11.

The year following the 1878 Henley Regatta, the Stewards passed a resolution pertaining to the definition of amateur as related to Henley entries. As the regatta had always been intended for amateur competition, the resolution drafted in 1879 stated, in part, that the entry of any crew outside of the United Kingdom must be accompanied by a declaration with regard to the profession of each member of the crew stating that the member “is not, nor ever has been, by trade or employment for wages a mechanic, artisan, or labourer.” Thus, any sort of professional, not just a rowing professional, was excluded from future competition at Henley. On April 8th of 1879, the “Shoes,” the one-time lumbermen from Monroe, received a cablegram from the Henley Stewards stating that “the Shoe-wae-cae-mette rowing crew, on account of their having been mechanics and artisans, will be barred from entering the lists at the forthcoming Henley regatta.”

The “Shoes” sought to obtain relief from the Henley restriction by arguing that because of their previous occupations, they could not qualify under the restrictive provision and asked if the restriction could be waived. The Henley Stewards responded by informing the “Shoes” that the published definition of “amateur” would be strictly adhered to. It would be more than a century before the restriction against so-called non-amateurs would be lifted.

After excoriating the “Shoes” in 1878, the New York Times took a more conciliatory tone and sided with the “Shoes” in 1879:

Much indignation is felt because of the action of the Henley Stewards who announce the regatta open to all amateurs in the world, and then frame restrictions that will exclude the great majority of American oarsmen . . . whose only offense is that they have worked for an honest livelihood and are bonafide amateurs under American rules.

– New York Times, May 22, 1879, 2.

An editorial appearing in the Sunday Dispatch (London) on July 13th, 1879, a year after the “Shoes’” win at Henley, pointed out the hypocrisy shown by the Regatta Stewards by noting the way in which “the poor Shoe-wae-cae-mette and other American amateurs were accused of working for their livings as though it was a crime,” while England’s own amateurs who were neither “blue-blooders nor millionaires” were not above “taking a benefit or pocketing a subscription (advance payment)” if it could be sufficiently glossed over.

The “Shoes” would continue to compete in regattas in America following their win at Henley, but by the summer of 1880, it was announced that they had disbanded after having been beaten at New Orleans by the Hillsdale Four Crew, three of whom had attended Hillsdale College in the Michigan town of the same name. Despite all the criticisms thrown at the “Shoes,” and despite the fact that they would never again row at Henley, the “Shoes” will be remembered in the annals of rowing history for having had one brief shining moment at Henley Royal Regatta.

Hurrah! the rowing “Shoes” (cont.)

The “Shoes” returned back to the States

and with them front-page news.

Remembered for their Henley win,

Hurrah! the rowing “Shoes.”