6 January 2026

By Edward H. Jones

* With apologies to American pop singer Nancy Sinatra who had the 1966 hit song “These Boots Are Made For Walkin’.”

In Part I, Edward H. Jones looks at the Shoe-wae-cae-mette rowing crew (the “Shoes”) and their participation at the 1878 Henley Royal Regatta.

Hurrah! the rowing “Shoes”

Edward H. Jones © 2025

The “Shoes” sailed off to England

to make some Henley news.

They won against Columbia.

Hurrah! the rowing “Shoes.”

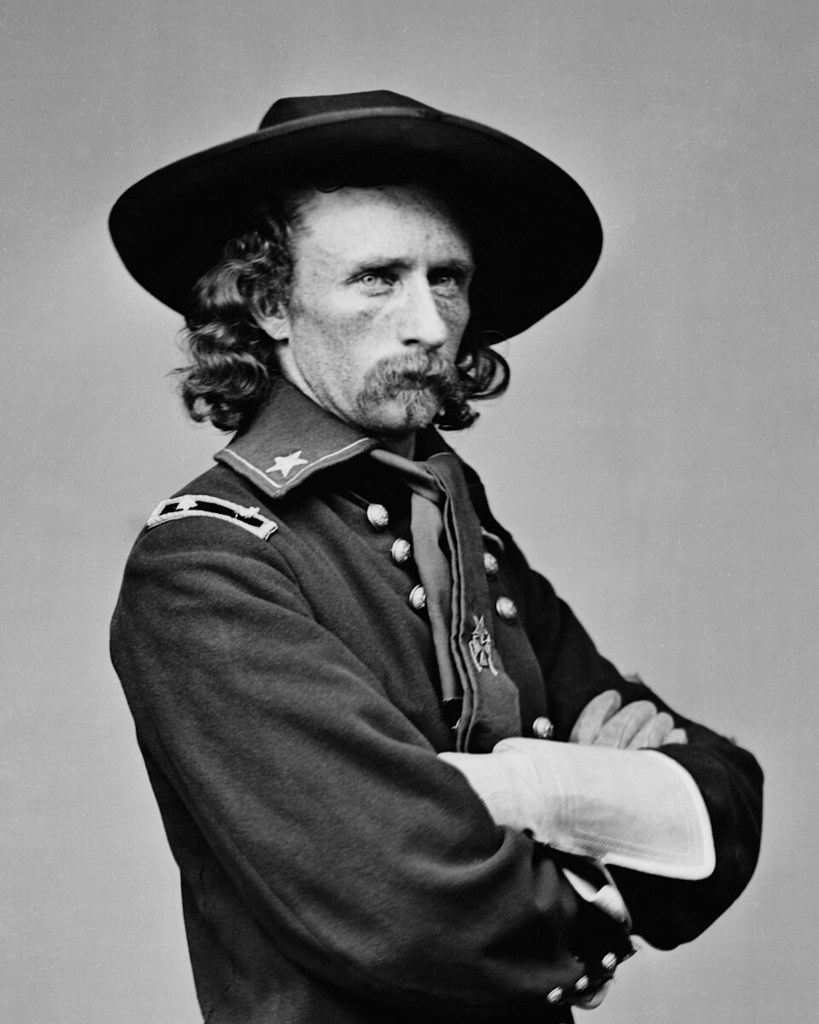

The first time I ever saw a reference to the Shoe-wae-cae-mette rowing crew, I just naturally assumed they were a nineteenth-century crew of Native American oarsmen. (I trust I’m not the only one who initially assumed this.) As it turns out, the “Shoes,” as they were called, were not a Native American crew, but were a nineteenth-century coxless four organized in 1874 and comprised of French-Canadian lumbermen residing in Monroe, Michigan, just south of Detroit. Interestingly, although the “Shoes” rowing crew didn’t appear to directly involve Native Americans, a two-time resident of Monroe who did become involved with Native Americans was George Armstrong Custer, the U.S. Army calvary officer whose encounter with native tribes in 1876 by the Little Bighorn River didn’t end so well for him.

The “Shoes’” name, according to a newspaper account at the time, was pronounced “shoe-wa-say-mitty” and is reportedly a Potawatomi word meaning “lightening on the water.” According to legend, some native Potawatomi men were suddenly caught in a rainstorm and took shelter under a natural arbor of wild grapevines by a river. Through the tangle of vines, the storm-bound men saw a beautiful play of lightening on the river, and they called out “Shoe-wae-cae-mette!” or “Lightening on the water!”

“Shoe-wae-cae-mette,” the name adopted by the American crew abroad, is Indian for “lightning in the water.” In Los Angeles it is called whisky. How names do change in a dry climate!

– Alameda (CA) Times Star, July 18, 1878, 3.

On June 1st, 1878, the “Shoes” won a three-mile, four-oared race at the Watkins Regatta on Seneca Lake at Watkins Glen, New York, earning the right to travel to England to represent America at Henley Royal Regatta that July 4th and 5th. The New York Times had nothing but praise for the men: “they are a wonderful crew, and have formed an inexhaustible subject for comment and speculation to American oarsmen ever since they burst like an erratic meteor upon aquatic vision at Saratoga in 1876.” The Times noted that the “Shoes” rowed in an old four-oared, paper-hulled boat – the Chas. G. Morris – that had been built years earlier by Waters & Sons boatbuilders of Troy, New York, and was designed to have a coxswain. The “Shoes” modified it for coxless racing. It would be the boat they would take to Henley, as nobody was willing to offer them a new boat. It was twenty-two inches wide, forty-one feet long, flat-bottomed, and sat high on the water. It weighed 128 pounds. The Times said that no other crew could, or would, row in it, but it seemed to suit the “Shoes” just fine. And while not as stylish as other racing boats, the “Shoes” had become so accustomed to their old boat that it was doubtful they could do any better, or as well, in a new boat, the New York Herald noted. “Their style of rowing, which was laughable in 1876, had greatly improved in the last two years,” the Times observed, “and it is no longer each man for himself.” Their rowing style is peculiarly their own and is notable for a “wonderful quickness of recovery and a long hold on the water,” the Times said.

On June 5th, 1878, shortly after their win at Seneca Lake, the “Shoes” boarded the steamship Alsatia at New York to depart for England and Henley. On board, they were cordially received, reported the New York Herald. They hung their boat, which had been “boxed” for transport, from the portside davits (boat hoists). The “Shoes” then lit up cigars, and in their usual “sans souci” style, according to the Herald, they roamed about the ship until its departure. Also travelling aboard the Alsatia was George W. Lee of the Triton Boat Club of Newark, New Jersey. Lee was the single-sculls winner at Seneca Lake and would also represent America at Henley. Expenses for the four members of the “Shoes” crew, their manager, a substitute oarsman, and George W. Lee all were covered by the Watkins Regatta Association.

As the Alsatia moved slowly from her dock, the New York Times reported that 100 rowing men who had assembled to bid the departing oarsmen God-speed gathered on the outer end of the pier and sent up volleys of cheers for the “Shoes” and Lee. Then, heard distinctly above the roar of the steamship’s exhaust blast came back an answering yell from the “Shoes” – a sharp “Yip-yip-yip!” that had so often announced their victories, said the Times.

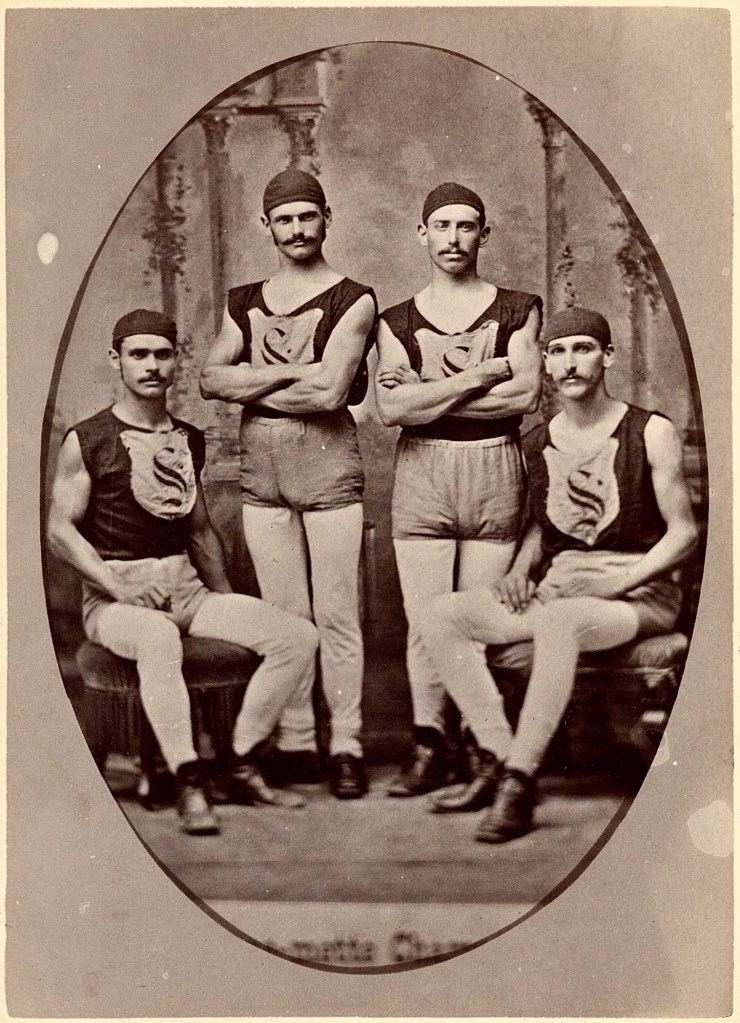

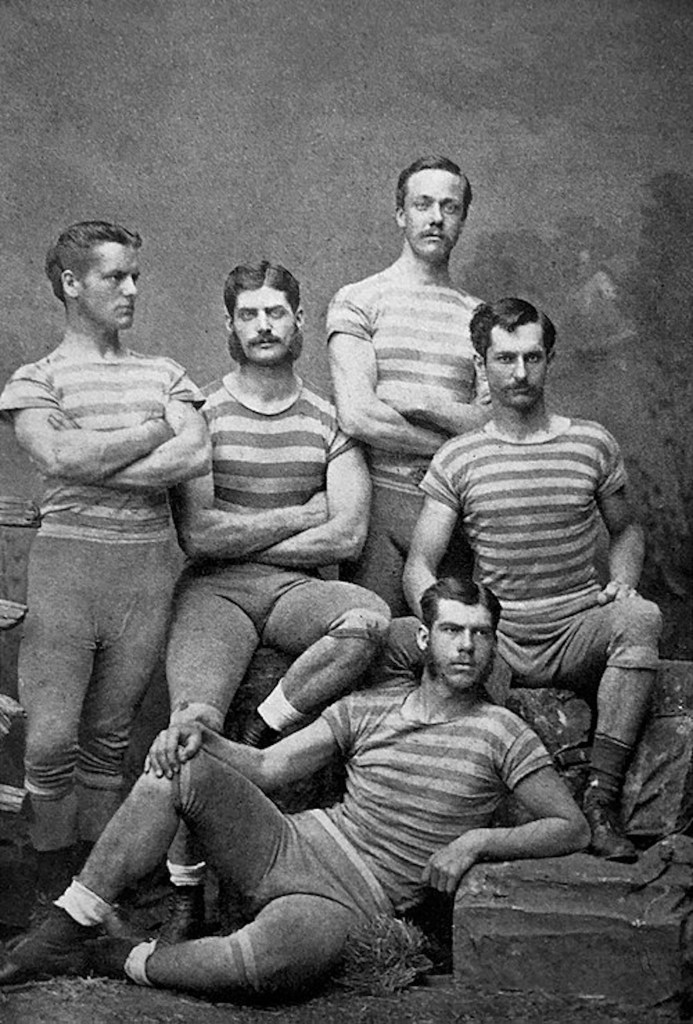

The “Shoes’” rowing positions, names, and ages were: Stroke – Stephen Dusseau 26; No. 3 – Henry Durell 25; No. 2 – Joseph Nadeau 23; and Bow and Captain – Moses Nadeau 27. The two Nadeau men were brothers. The average weight of the crew was 145 pounds. The men were described as wiry, dark-complexioned, and even swarthy, an appearance no doubt acquired from engaging in outdoor activities. They had all led lives of hunters and fishermen except for their stroke Dusseau who had helped a relative run a hotel business. All of the “Shoes” were unmarried, and they were all were of limited means as evidenced by the fact that they were taking an old boat to race at Henley. Their boat had absolutely nothing going for it except its record of previous wins.

Not having enough money to buy a good boat, the Shoe-wae-cae-mettes carried to England a miserably old, heavy, and clumsy shell, in which good oarsmen would have disdained to pull.

– New York Times, July 5, 1878, 4.

On June 18th, the “Shoes” arrived at Southampton, England, and after much difficulty, secured apartments at Henley near the river. They were reportedly in good health, with only one of the men suffering from seasickness.

The Shoe-wae-cae-mettes complain of a cold reception by English oarsmen. The “Shoes” were not collegians, did not put on style enough, and were “vewy vulgah, you know.”

– Brooklyn Union, August 1, 1878, 2.

The “Shoes” were described as a “rough-looking lot, who dressed in blue flannel shirts and rough clothing of the woods,” startling members of the proper British boat clubs situated along the Thames. It was said that one of their chief amusements while at Henley was to hurl plugs of chewing tobacco at a portrait of Queen Victoria which ornamented their Henley boathouse wall. To the British, the “Shoes” surely must have seemed like a rough-cut bunch of provincials from the untamed backwoods of America.

As oarsmen, the “Shoes” reportedly “had not the slightest semblance of form,” but had rowed so long together that they were able to attain a short, choppy stroke rate of at least 45 strokes per minute, maintaining that rate to all the way the finish line.

The Shoe-wae-cae-mettes, in practice, at Henley, England, appeared in such scanty habiliments that the people commented sharply thereon, and endeavored to delicately suggest the propriety of covering their nakedness.

– Springfield (MA) Daily Republican, July 8, 1878, 5.

On July 3rd, the day before the first day of the 1878 Henley Regatta boat races, the temperature in London reached a high of 91°F in the shade. Moreover, during the week of the Regatta, an “exceedingly high temperature” resulted in an increase in heat-related deaths over the previous week. Therefore, this could have accounted for, but perhaps not have totally justified, the “Shoes” practicing in “scanty habiliments” (whatever attire that was). Therefore, it can fairly be said that by British standards, the “Shoes” came across as a bit crude, rough-hewed, and apparently semi-nude. In short, they were the bad boys of late nineteenth-century rowing.

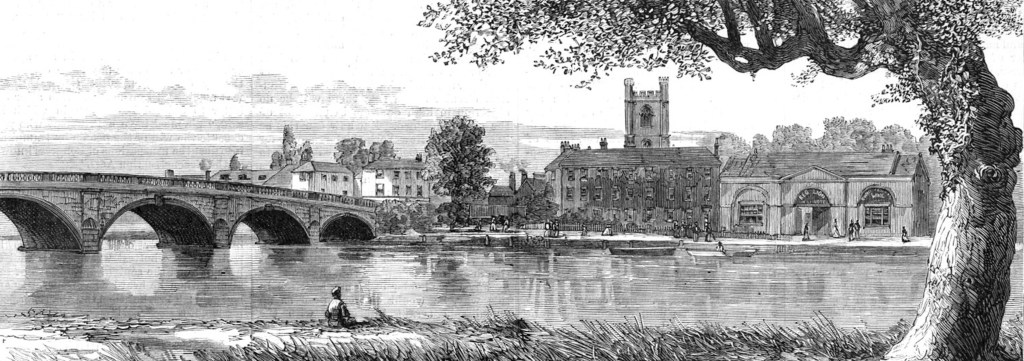

Henley, the oldest town in Oxfordshire, is thirty-five miles northwest from London, and is a typical sleepy English town, whose only life is during regatta week, coming once a year, its only other relief from absolute stagnation being weekly market-day, when for a few hours its one street of any importance or business is thronged with burley farmers, bleating sheep, and lowing herds.

– Harper’s Weekly, July 20, 1878, 570.

The first event on July 4th was the Diamond Sculls match race for single sculls which involved George W. Lee. The Diamond Sculls was the premier sculling event at Henley. Harper’s Weekly reported that it was a well-contested and spirited race, and Lee would have won had he not unfortunately stopped within twenty feet from the finish under the impression that he had crossed the line. Two more strokes would have carried him safely over the line, Harper’s reported. His competitor kept on and won by less than a quarter of a boat length.

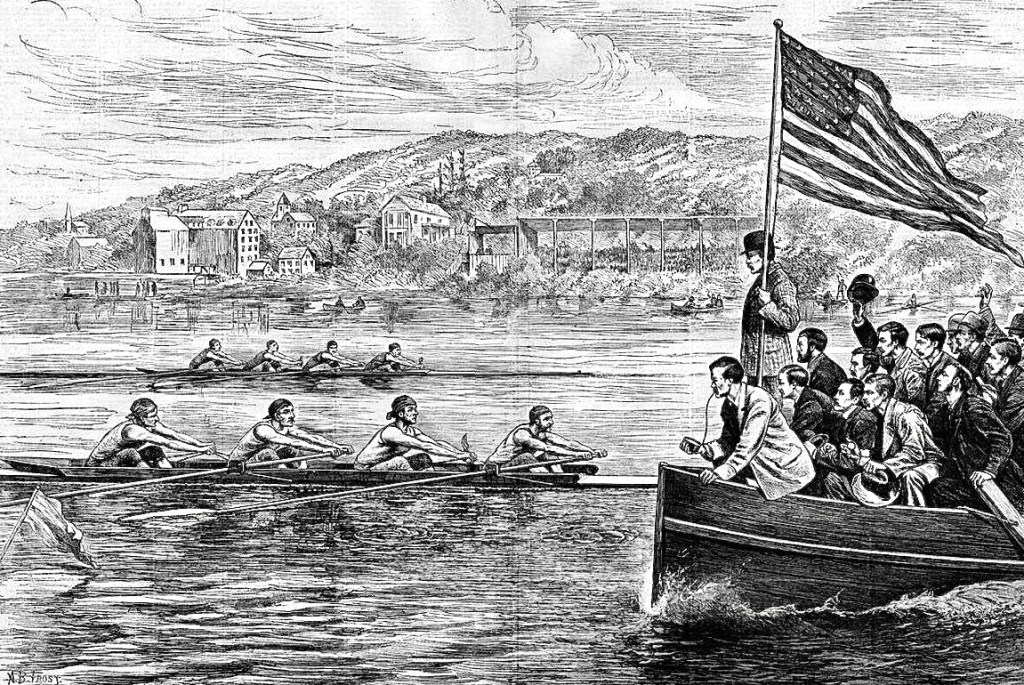

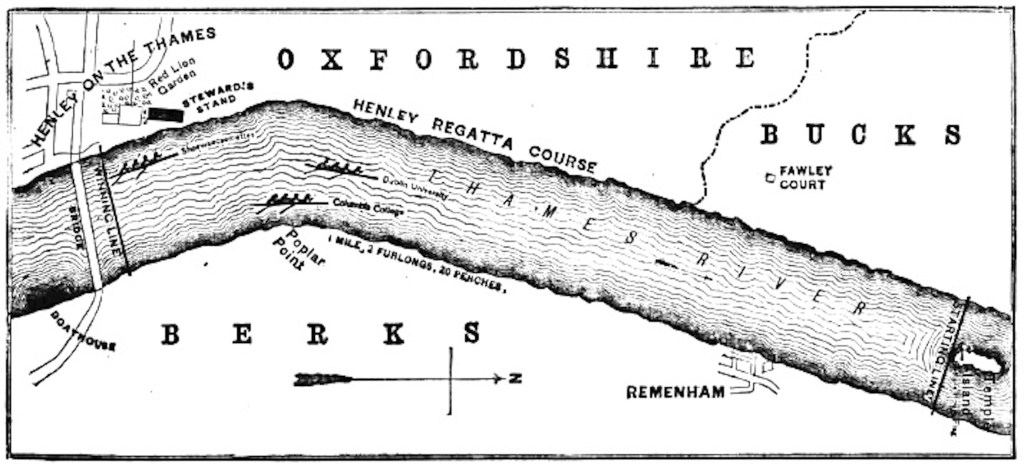

The next race of the day was the first trial heat in the four-oared contest for the Stewards’ Challenge Cup, described as a massive silver vase valued then at more than $400 ($13,000 today) and engraved with the names of winners from the past forty years. The race distance was 1.3 miles. The contestants were the “Shoes” and Columbia College (now University) from America and the University of Dublin.

As reported by Harper’s Weekly, at the start of the race, the Dublin crew took the lead, but the “Shoes” soon pressed ahead, and the Columbia crew, “rowing in grand form,” rapidly lessened the distance between them and the Dublin crew. As Columbia and Dublin were rounding a bend in the River Thames, the Dublin crew crashed into Columbia’s boat just as the latter was beginning to overtake Dublin, this despite the shouts of the umpire: “Dublin, take your right course!” The Dublin and Columbia boats disentangled themselves, and when they did Columbia was leading Dublin. But long before this, the “Shoes” had taken a decided lead, having made up what they had initially lost by a uniform stroke rate of 46 per minute from the start. At the time of the foul, which occurred at the end of one mile, the “Shoes” were ahead of the fouling boats. Upon witnessing the foul, the “Shoes’” bowman commanded his crew to “ease all,” and dropping their stroke rate to 40, the “Shoes” easily proceeded to the finish line. For several boat lengths the Nadeau brothers of the “Shoes” crew pulled with only one hand, waving their red caps in response to the cheers from shore. As they passed the grandstand, the “Shoes” raised their stroke rate to 48 to afford the spectators an exhibition of their rowing prowess. The “Shoes” crossed the finish line many boat lengths ahead of the Columbia crew.

Columbia, who had come in second, requested that that they be allowed to row in the final heat because of the foul, but the race Stewards denied the request on the ground that the “Shoes” were so far ahead that they could not have been caught, and the foul did not for all practical purposes affect the outcome of the race. Thus, the “Shoes” were the first Americans to win a heat at Henley. As for the Columbia four, they later would win the Visitors’ Grand Challenge Cup by defeating Hertford College, Oxford, on day two of the regatta, thus becoming the first American crew to win a Cup race at Henley.

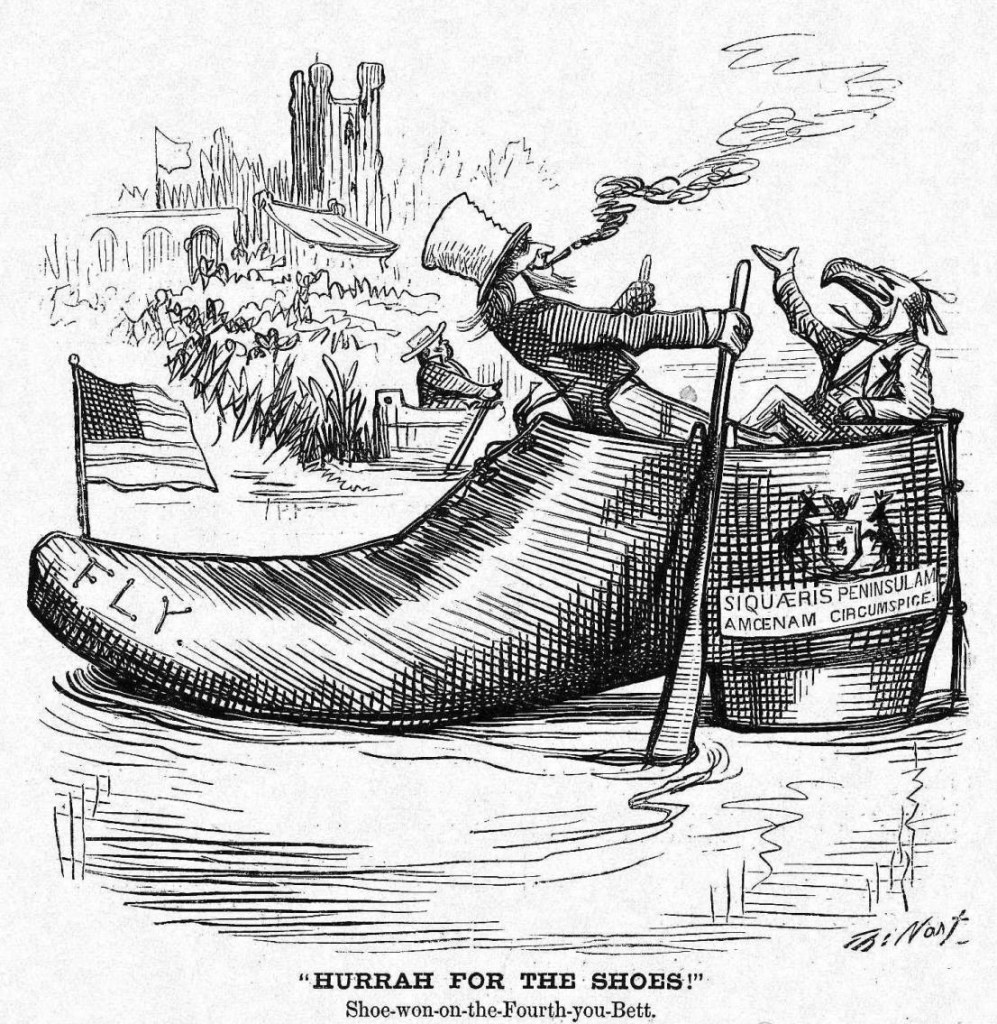

To celebrate the “Shoes”’ first-heat victory, Harper’s Weekly published a cartoon by the celebrated American editorial cartoonist Thomas Nast. The victory is represented by a giant shoe being rowed by a cigar-smoking Uncle Sam symbolizing the United States and coxed by an eagle, another symbol of the United States. At the shoe’s toe is an American flag and the letters FLY. I can only speculate that the letters are intended to suggest the quintessentially American traditional dessert known as shoofly (shoefly) pie. The side of the giant shoe acknowledges the “Shoes’” home state of Michigan by displaying the Michigan Great Seal showing an elk and a moose, both symbols of the state, and an eagle symbolizing the United States. Below the seal is a banner displaying the Latin state motto: Si quaeris peninsulam amoenam circumspice (If you seek a pleasant peninsula, look about you). In the distance of the scene is the iconic tower of Henley’s St. Mary’s Church visible from the Thames. Near the shoreline, a corpulent gentleman rows a wooden tub, the meaning of which I have no idea. The cartoon’s caption reads “Hurrah For The Shoes!” Shoe-won-on-the-Fourth-you-Bett, a play on the “Shoes’” lengthy hyphenated name.

The ”Shoes’” second day of racing at Henley would unfortunately not be as successful as the first due to an unexpected turn of events, and harsh criticism would follow the “Shoes”’ Henley appearance.

These “Shoes” Were Made For Rowin’ – Part II will be published tomorrow.