21 November 2025

By Edward H. Jones

With the 141st edition of the annual Harvard-Yale football game (“The Game”) scheduled for Saturday, November 22 at New Haven, Connecticut, HTBS decided to look back at the life of a late nineteenth-century Irish immigrant who became a beloved mascot of the Harvard University athletic teams, including its rowing crews.

The Orange-Man of Harvard

By Edward H. Jones © 2025

Beloved by all the students,

he was Harvard’s biggest fan.

An Irish brogue and whiskers,

that was John the Orange-Man.

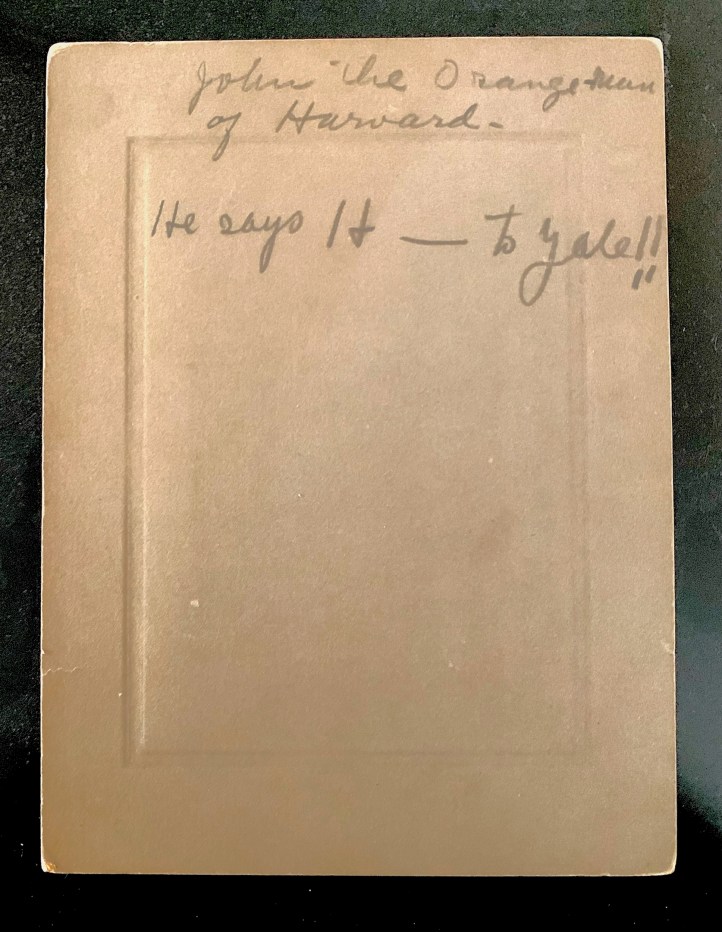

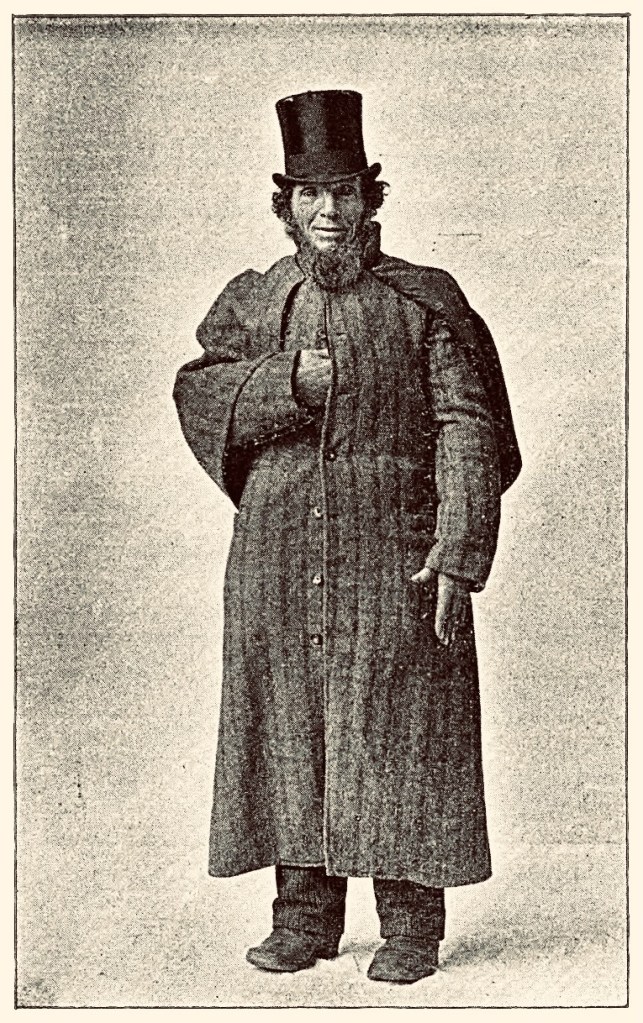

Many years ago, when I had lots of free time and little money, I was browsing around a shop that bought and sold antiquarian books and collectables. While there, I came across an interesting sepia-toned, cabinet card-sized photograph for sale. The undated image, taken in a studio, was mounted on card stock and showed a strange-looking, wildly bearded character wearing a top hat and what appeared to be a wrinkled academic robe. His fist is raised, and he’s holding a makeshift flag. On the back of the photo mount, handwritten in pencil, are the words “John the Orange-Man of Harvard” and “He says H ___ to Yale!!” I bought the photo, and given my pecuniary status at the time, I couldn’t have paid more than a few dollars for the item, if that. (I had previously purchased American Civil War-era cartes de visite, cabinet cards, stereoscope cards, and tintypes at this shop typically for only a few dollars apiece.) So, who was this Orange-Man of Harvard and what is his connection to rowing?

Because my purchase was before the advent of the internet, when I tried to research the identity of this individual, I repeatedly came up empty. And although the photo was taken in a studio, there was no identifying information. Eventually, I filed the photo away and didn’t think about it any further. Fast forward a half-century later. Now, with the internet making historical research considerably easier, I decided to renew my search for the identity of John, this time finding an abundance of information. John was such a prominent fixture on the Harvard campus that he warranted two biographies, one in 1891 – The Story of John the Orange-Man: Being a Short Sketch of the Life of Harvard’s Popular Mascot by one of his “Frinds” [sic] – and one in 1892 – The History of John the Orange-Man by Henry Fielding. Both publications can be found online at the HathiTrust Digital Library website.

John the Orange-Man was born John Lovett around 1829 in the small village of Kenmare in County Kerry, Ireland. Although his tombstone indicates he was born in 1829, the exact date of his birth has never been conclusively determined. He was the son of “poor but honest” parents and by one account he was one of twelve children – five girls and seven boys. His father was a farmer who leased and worked a small plot of land and supplemented his income by selling peat he harvested from the surrounding bogs. When John was eight years old, he reportedly was sent to the public school, but he only attended for two years, that being the extent of his formal education. When John was in his teens, Ireland was devastated by what became known as the great potato famine (1845-52) caused by a fungal blight which ravaged the country’s crop of potatoes, one of Ireland’s main food staples at the time. The famine forced many families and individuals to emigrate to North America including John who, around the age of twenty-five, with Ireland still reeling from the effects of the famine, set out for the United States.

On May 19, 1854, John Lovett arrived in Boston, having departed from Liverpool, England, six weeks earlier on a ship named the Chapin. He eventually settled in Cambridge. He lived not far from the campus of Harvard University and soon found work doing odd jobs. As the story goes, John was watching some students playing ball on a hot afternoon when they asked him to fetch them some water. So, he goes home and prepares a large pitcher containing a concoction of ice water, molasses, ginger, and vinegar. The drink would have been known as “switchel” or “haymaker’s punch” to nineteenth-century farming types like John, but would have been unfamiliar to the upper-crust Harvard men. It was a quenching and rehydrating beverage for field workers similar to the sports drinks of today. While the proponents of the drink may not have completely understood how it acted upon the body physiologically, it nonetheless contained molasses for sweetness, energy, and electrolytes; ginger for a bit of bite like ginger ale; and vinegar for a little tanginess like lemonade. When John returned to the students with his homemade brew, they liked the drink so much that they asked him to fetch them some more. For his efforts they gave him two dollars. The students befriended John, and they suggested that if he could obtain some fruit and come around to their rooms in the evenings, he could make money selling them the fruit as late-night snacks. So began John’s career as a peddler of fruit which would earn him the moniker “John the Orange-Man.” He initially began peddling his fruit from a hand-held basket. In later years, though, as John got up in age, students took up a collection and purchased for him a cart and female donkey. John named the donkey Radcliffe after the nearby women’s college because he claimed she was the only one of her sex permitted on the then all-male Harvard campus. The cart and donkey made it easier for him to peddle his wares and make his daily rounds on Harvard Yard. The cart was white with each side proudly displaying the letter “H” painted in Harvard crimson. As students would assemble around the cart to buy fruit, John would regale them with stories of Harvard’s athletic victories of years past. He reportedly would also lend money to students who had squandered their allowance and had run out of money before the month had run out of days.

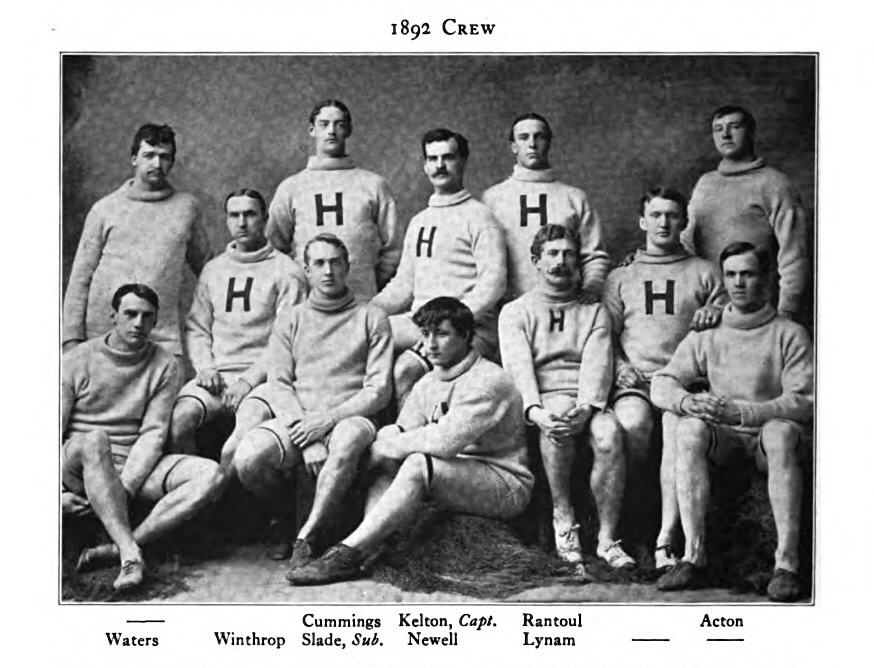

With John’s friendly demeanor and enthusiasm for and devotion to Harvard, students regarded him as the unofficial mascot of the school’s athletic teams. It was said that he went with the students to every game and to every boat race in which “the Harvard boys” were contestants. His love of Harvard was as intense as his good-natured hatred of rival Yale. An oft-told story has a group of visitors touring Harvard’s campus and pausing at a gateway entrance. John was there peddling with his basket of fruit. Seeing the Harvard motto “Veritas” (Truth) inscribed over the gateway, one of the visitors, thinking he would have a bit of fun at John’s expense, turned to him and asked if he knew what “Veritas” meant. “I’m not quite sure,” John said, “but I think it means ‘To hell with Yale.’”

A typical example of John’s fervent support for Harvard was demonstrated during a baseball game against Yale. Just before a Harvard player stepped up to bat, John, who was in attendance sporting a top hat adorned with a crimson hatband and wearing a crimson shirt, walked up to home plate and brushed it off with a broom. When greeted with applause from the Harvard men, John “bowed his acknowledgement most gracefully” according to the Boston Herald. A display of John’s impish behavior involved another baseball game against Yale. Just before Harvard came to bat for the first time, John circled the home plate three times hoping to impart “the luck of the Irish” to the Crimson men. Then, “bowing gravely,” he touched his silk top hat to the plate which elicited wild cheers from the Harvard faithful according to the Boston Post. At yet another Harvard-Yale baseball game, the Boston Globe reported that John summoned the baseball gods to act in Harvard’s favor by executing a “ghost dance” reminiscent of that performed by native tribes in the American West. He then waved his crimson flag and while shaking his head began casting all sorts of spells over the men from Yale.

John, the orange man at Harvard, has just come, and the whole Harvard side of the field has broken into the wildest cheers as John swings the crimson flag above his head.

– Boston Globe, November 22, 1890, 1.

When students were busy studying in the evening, John reportedly would shuffle into their rooms, and with a “Good evening, friend” would leave some oranges, or bananas, or figs that the student might want. If the student wasn’t there, John would leave them something anyway and kindly collect what he was owed at the end of the month. It was said John never kept books but always knew exactly what each student owed.

John’s love of Harvard was equaled by his love of his adopted country. On September 11, 1875, twenty-one years after he had set foot on American soil, John officially petitioned the government to become a naturalized citizen of the United States of America. With “his † mark” he signed the petition.

“If you ever attended one of the big games on an eastern gridiron, . . . if you have ever watched breathless from the observation train the crimson crew sweep down the Hudson or the Thames (New London, CT), you must remember John the Orangeman.”

– The Daily Sentinel (Rome, NY), August 28, 1906, 7.

John would have been a familiar face to Harvard’s rowing crews. Once, a crew manager requested green apples from John when it became necessary to reduce the weight of the coxswain – an unusual weight reduction regimen to be sure. Across the Atlantic, the victory of the Cambridge University crew over Oxford University in the 1906 edition of their annual Boat Race was said to have been attributed to the winning crew’s diet of eggs, prompting the Harvard oarsmen to begin daily devouring large quantities of the yolk-filled ovoids. This, in turn, prompted John to give the matter consideration, and it was rumored he would add eggs (hard-boiled, I assume) to his stock of food offerings to peddle on campus and at the athletic fields. He reportedly did not, however, plan to change his moniker to John the Egg-Man.

In 1905, the Boston Globe published a bizarre cartoon to illustrate an article on an anticipated match race between Harvard and Cornell Universities on Boston’s Charles River. The cartoon shows Cornell crew coach Charles Courtney paddling a canoe whitewater style. He is competing against John the Orange-Man who is steering his donkey cart that sits aboard a strange paddle-wheeled vessel powered by his donkey Radcliffe as she plods along a treadmill. The caption reads “Cornell vs. Harvard: Why Not Settle All Questions of Superiority by Letting Coach Courtney and John the Orangeman Go Over the Course?” Although I fail to grasp the meaning of the cartoon (I welcome any HTBS readers to weigh in), it nonetheless shows that John the Orange-Man’s celebrity extended into the realm of rowing.

John considered everyone a friend, from the President of Harvard University to the President of the United States. One of his “warmest” friends was President Theodore Roosevelt (class of ‘80). After Harvard defeated Yale in football in 1901, John supposedly wrote to Roosevelt telling him of the game’s outcome. Roosevelt’s written reply was said to have been one of John’s most prized possessions which he always carried so he could show it to his friends. Other prominent men who were friends of John included U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes (class of ‘61) and American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Theodore Roosevelt’s fifth cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt (class of ’04), who would follow in his relative’s footsteps and become a U.S. President, most likely was aware of and perhaps even purchased fruit from John the Orange-Man.

A modern-day account of John’s life states that around 1900 or so, he began selling copyrighted souvenir photos of himself to no doubt financially capitalize on his celebrity. That being so, I would be comfortable giving the photo I purchased at the antiquarian bookshop a half-century ago a date of circa 1900.

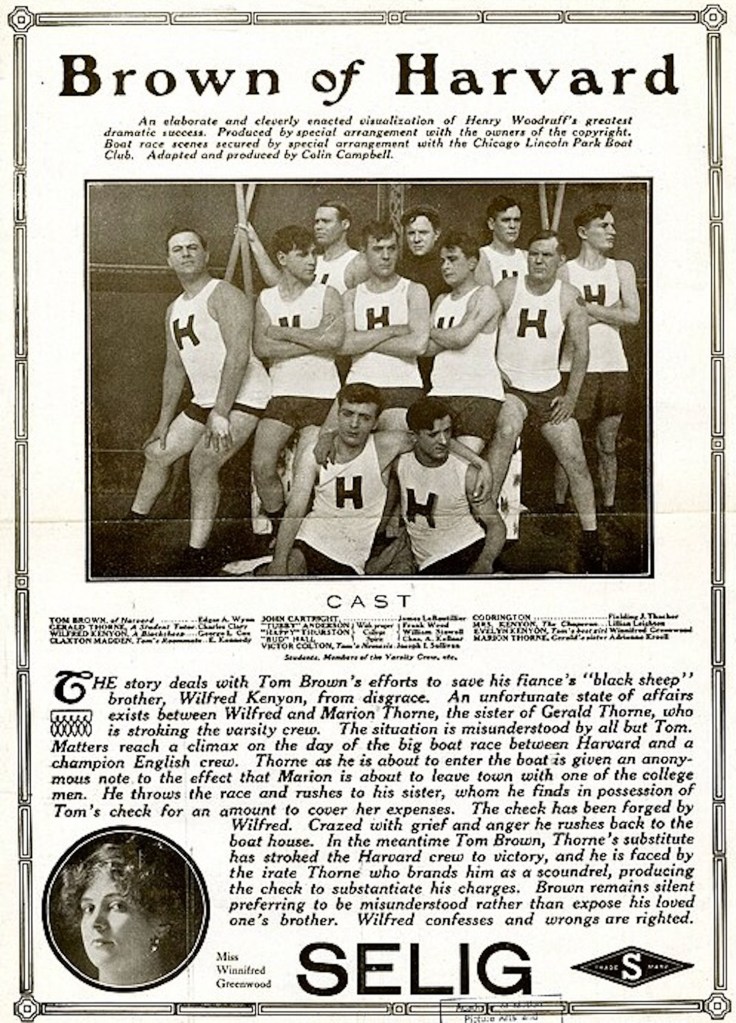

“John, the Orange Man,” affectionally known to every Harvard student for a half century, the mascot of the football and the baseball teams and Harvard crews, and the idol of the dormitories, is going on the stage. He is going to play himself in Henry Miller’s production of “Brown of Harvard,” which is soon to be presented at the Princess Theater, New York.

– The Daily Item (Lynn, MA), February 21, 1906, 10.

Early in 1906, John was invited to New York City to play an on-stage role he had been rehearsing his entire life . . . that of himself. The production was Brown of Harvard that told the story of the title character, Tom Brown, and the affairs and the fortunes of college life at Harvard and its rowing crew, with the excitement of a great race against an English crew as the climax. The play was reported to have had a “very well managed” boat race scene. John the Orange-Man was scheduled to appear in the first scene, his fruit basket on his arm, to ply his trade before the theater audience. The Evening World (NY) reported that John was the star of the evening when he made his debut. He “weathered the gale of applause” that swept across the stage, the World reported. The Sacramento Bee reported that upon his first appearance on stage “he received an ovation that almost bowled the poor old chap off his pins.” It was reported that John waved a crimson handkerchief in acknowledgement and bowed as low as his years and his basket would allow. “John was the one true joy of ‘Brown of Harvard,’” the Evening World proclaimed. The Minneapolis Star Tribune reported that some of the Harvard graduates “will undoubtedly visit the theater especially for the purpose of recalling old times by catching a glimpse of John the Orange Man” known to thousands of Harvard men throughout the world.

In late summer of 1906, John had taken seriously ill with acute intestinal distress and badly needed to have surgery. He survived the surgery – the removal of a cancerous growth – “but his recuperative powers were not sufficient to meet the drain on his strength,” and on August 12, four days after admission, he died at Massachusetts General Hospital with colon cancer as the official cause of death. His age at death was believed to be around 77, although we will never know for sure. An obituary in the Syracuse Herald-Journal asked the crutial question: “How old was John when he died?” The article then noted that “John himself could never tell to his dying day in what year he was born.” If there is one consistency in the records documenting John’s life, it is the inconsistency of the underlying information, especially when it comes to dates and ages.

John is buried next to his wife Mary – a certain “charmin’ Mary Hallissey” – at St. Paul Cemetery in the Boston suburb of Arlington. Their headstone can be seen on Find a Grave. Mary had preceded John in death by five years. Two months after John’s passing, the Harvard athletic committee officially agreed to permit Miss Katherine Lovett, John’s thirty-three-year-old daughter, to sell fruit, peanuts, popcorn, and other delicacies to the Harvard students at all football and baseball games. She would be assisted by a retinue of young urchins headed up by a local errand boy named “Mugsey.” Thus, Miss Lovett was able to continue the legacy her father had begun.

“We all thought a good deal of John,” declared a prominent Harvard man recently. “As an orange man he was indispensable. As a mascot we could never have got along without him. It was John, in his silk hat and red ribbons, who pulled Harvard through many a trying ninth inning, who rallied the exhausted football giants in the last five minutes at the stadium. Dear old John! He was as much a part of Harvard as the college yard.”

– Daily Record (Long Branch, NJ), August 30, 1906, 8.

As the Harvard and Yale players put on their pads for their annual gridiron clash this year at New Haven, and when the rowers from both schools slide their oars through the oarlocks this spring as they prepare to slice through the waters of the Thames in their racing shells during their annual boat race at New London, just know that a bewhiskered fruit peddler from Ireland will, in all likelihood, be looking down upon both contests with unbridled enthusiasm and delight.

____________________

P.S.: For all the grammarians among the HTBS readers, know that because of all the variations in how John’s name appeared in newspaper accounts, biographies, and other sources, I struggled with how his name should be written – comma, no comma; hyphen, no hyphen; upper case, lower case. I eventually decided to go with what had piqued my interest in the first place: the cabinet card photo of John. Whoever it was who wrote on the back of John’s photo card, I’m believing the writing just might be the closest thing we have to the man himself, and that is how his name should appear: John the Orange-Man of Harvard.