17 October 2025

By Edward H. Jones

In an era when rowing was America’s most popular spectator sport, no one was a better oarsman than a short and stocky glassblower from Pittsburgh.

The Little Engine

By Edward H. Jones © 2025

Pittsburgh’s Jimmy Hamill was

an oarsman quite supreme.

This “Little Engine” rowed as though

his arms were powered by steam.

Though Jimmy Hamill’s life was short,

he showed determination.

He beat his foes to become the fastest

sculler in the nation.

On a perfect August afternoon in 1862, a twenty-three-year-old oarsman from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was about to row the biggest race of his life. James “Jimmy” Hamill, a glassblower by trade, had traveled across the state to Philadelphia to compete against Joshua Ward, the reigning single-sculls rowing champion of America. Weeks earlier, Hamill and Ward had agreed to row two races, one on August 12 and one on August 13 on Philadelphia’s Schuylkill River. The winner of each day’s race would walk (row) away with a purse of $500, or $1,000 for winning both races, worth over an estimated $32,000 in today’s dollars. Hamill would win both races, and in doing so would become the new American single-sculls rowing champion. During his professional rowing career, Hamill contested some twenty-two major single-sculls races, losing only five. During the decade of the 1860s, he competed for the title of American Sculling Champion eight times, emerging victorious six of those times. No other professional oarsman would claim as many American sculling crowns. His wins would put Pittsburgh squarely on the rowing map. His wins would also begin a period of Pittsburgh dominance in the sport of rowing that would include both men and women and would last for twenty-five years. Moreover, in Hamill, Pittsburgh can boast of being the home of the best professional oarsman America ever produced.

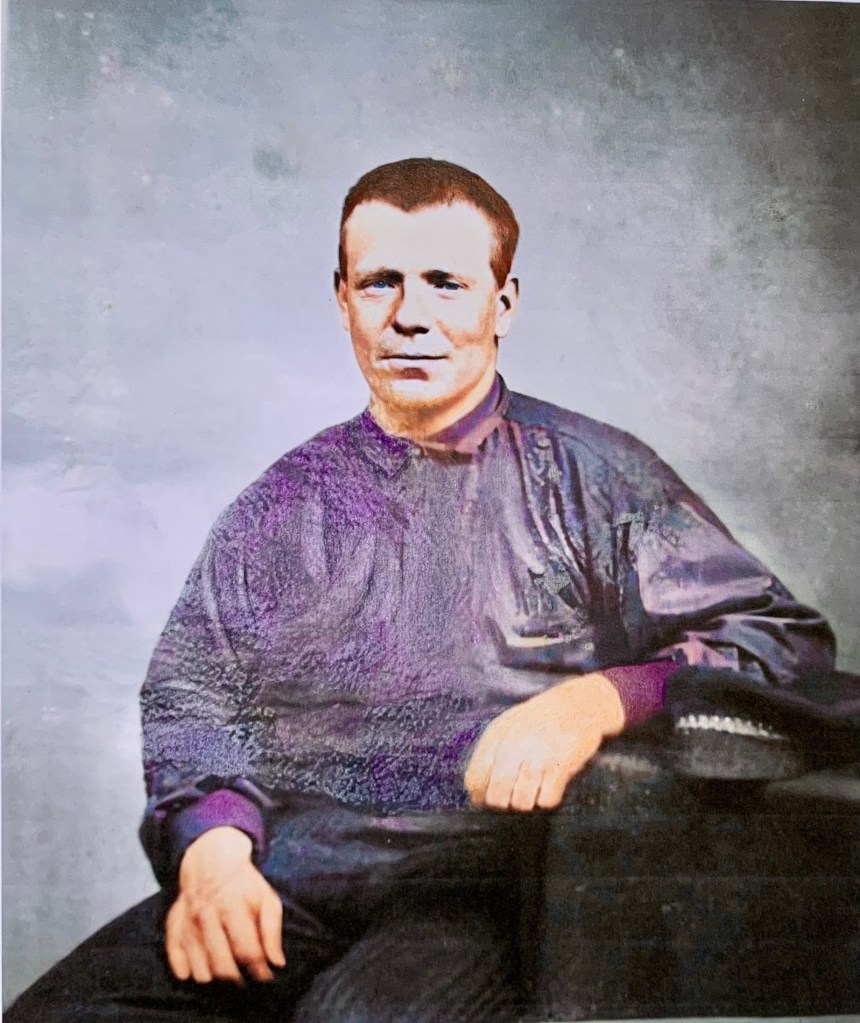

James Hamill was born in October of 1838 in what is now Downtown Pittsburgh. He grew up a stone’s throw away from and within sight of the Allegheny River, which converged with the Monongahela at Pittsburgh to form the Ohio. As a young man, he took up the trade of glassblowing which resulted in him developing a powerful set of lungs that served him well as a rower. In fact, it was said he had lungs like a forge bellows, suggestive of his occupation. He was only five feet, six inches high, yet was described as “thick set and muscular in his upper development, but rather spare in his lower extremities.” When in training, Hamill weighed about 150 pounds. The New York Clipper asserted that when stripped, Hamill exhibited “muscle of the toughest description, not unlike ‘a bag of almighty hard potatoes.’” What he lacked in height, he no doubt made up in “pluck and wind,” described as “two indispensables in a race on the water.” Because of his short, quick rowing strokes and his ability to keep up his piston-like action, he was dubbed the “Little Engine” by the press. His rowing style was described as “dreadfully faulty” but well-suited to a man of his build. Although he pulled his strokes almost entirely with his arms, with his immense strength he was able to make his unorthodox rowing style work to his benefit. Because he didn’t have the benefit of the sliding seat which wouldn’t be patented until 1870, Hamill had to contend with rowing on a less-efficient, bench-like fixed seat, putting him at a disadvantage because of his short stature and making his accomplishments all the more impressive.

It was said that Hamill had commenced his career as an oarsman at “quite a tender age.” His early races were confined to Pittsburgh’s three rivers where he won some thirteen out of fourteen contests he competed in. Outside of Pittsburgh, however, as an oarsman he was a relative unknown. Hamill made his national rowing debut by winning a first prize in the Boston Charles River Regatta on July 4, 1862. His boat was appropriately named the Pittsburgh. He had entered the regatta’s two-mile, single-sculls race with a turn. In this race competitors had to row one mile upriver to a stake boat, turn the stake, and row one mile back to the start.

At the firing of the starting gun six competitors all went upriver at a “lively” stroke rate. Upon reaching the stake boat, Hamill, sporting a blue shirt and red cap, had taken a good lead. He quickly turned the stake and headed for home, increasing his lead with each stroke. Twenty-thousand spectators witnessed Hamill win the Boston Regatta and cross the finish line reportedly looking none the worse for wear. In fact, he was so far ahead that most of the onlookers, judges included, didn’t believe he was a contestant. No customary gun was fired to signal the winner until the runner-up rowed past the judge’s boat and assured them that Hamill had won the race fair and square. Hamill’s unexpected victory earned him $75, equal to over an estimated $2,400 in today’s dollars.

To illustrate the popularity of rowing compared to other sporting events at the time, later that fall, on September 18, an estimated crowd of at least ten-thousand spectators watched the Eckfords of the eastern district of Brooklyn defeat the Atlantics of the western district of Brooklyn, 8 to 3, in the third and deciding game of a best-of-three-game series for the 1862 baseball championship of America. Although this was then considered the largest crowd ever to witness a baseball game, it was only half the estimated number of spectators attending Boston’s Fourth of July Regatta.

The comparative ease with which Hamill won the Boston Regatta induced some of his friends to suggest he race against Joshua Ward, the then-reigning sculling champion of America. By that September, after challenges and responses were exchanged between the two oarsmen, Hamill was ready to take on Ward.

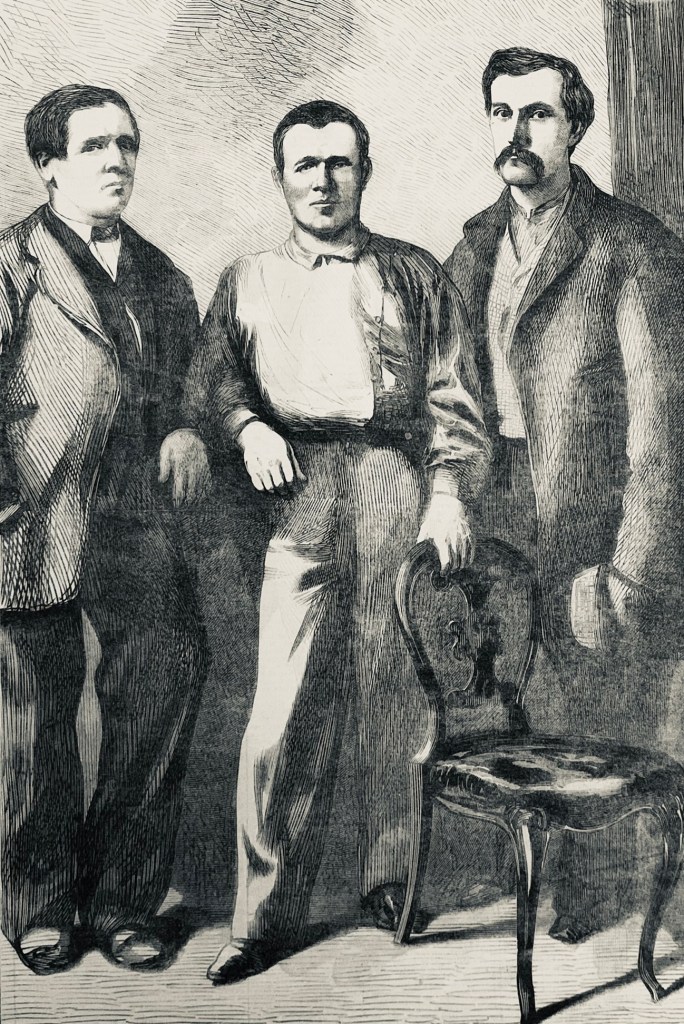

Joshua Ward was a native of Newburgh, New York, described as a place where “good oarsmen ‘sprout’ up naturally, like vegetation, requiring no hot-house or artificial forcing.” The comparison was no doubt a reference to Joshua and four of his brothers, all of whom were skilled and competitive oarsman. Joshua was six feet tall, of wiry build, and of “strong muscular power.” The Philadelphia Inquirer described Ward as “long bodied” with “great length of reach”— clearly an advantage to an oarsman. According to Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, Ward was “well-proportioned,” with a “broad chest” and a “stalwart frame giving him the appearance of one capable of great exertion and endurance.” He was also described as having mild blue eyes, good features, and thin lips with “regular” teeth, as if certain facial and dental characteristics were a prerequisite for sculling success. At age twenty-four, Ward had defeated some of the best scullers in America. His friends had insisted that no man had yet been found who could push Ward hard enough to test his rowing prowess. Those friends obviously never saw Jimmy Hamill row.

Friends of Ward drew up articles of agreement which Hamill signed without making any changes. The agreement called for two sculling races on Philadelphia’s Schuylkill River on August 13and 14, 1862, consisting of a three-mile race and a five-mile race for $250 “a side” for each race. This meant that the financial backers of each side (each contestant) would put up a purse of $250 for each of the two races. Thus, the winner of each race would come away with the entire $500 per race to be shared with his respective backers, with a potential to come away with $1,000 for winning both races (worth over $32,000 today). Roughly a week before the scheduled races, Hamill and Ward arrived in Philadelphia, along with their boats and accompanied by a few of their friends. The men commenced their daily workouts, often in sight of each other, on the Schuylkill River which had been selected as a neutral racecourse.

Hamill was nearly twenty-four years old at the time. Because he was a relative unknown in the world of competitive sculling, he was looked upon by some as a third-rate oarsman. In fact, rather than sending a reporter to cover his performance in Philadelphia, the Pittsburgh Post relied upon Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times and the New York Clipper to provide accounts of Hamill’s exploits. According to the Clipper, Hamill was very ambitious and was always anxious to display his skills against some first-rate oarsman. The Spirit of the Times described Hamill as having a “short neck, full face, and large head.” With red hair and blues eyes, his countenance was described as “florid” but his expression “determined.” The New York Herald, which called him a “rising young oarsman,” reported that his muscular development was “a study for a sculptor, for there was not an ounce of superfluous flesh on him.”

Many hundreds of visitors had gathered in Philadelphia to see Ward and Hamill compete. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that “a considerable sprinkling of petty gamblers were on hand plying their nefarious vocation.” One poor fellow, who was certain he could pick out the “little joker” in an apparent game of three-card monte, lost sight of not only the joker but his pocket watch, as well. Fortunately, the vanishing watch was returned to the duped gentleman with assistance of the police.

Despite Hamill being considered a third-rate oarsman, he won both races, handing Ward what the New York Clipper called “a most inglorious defeat.” Hamill, the relative unknown, had brought down the reigning champion. “Ward, we understand, admits that Hamill is the better man, and therefore it is not probable that the two will come together again in a match race” the Clipper predicted. With Hamill’s victory, the American championship of the single sculls had passed from the East to the West, from the flowing waters of New York’s Hudson to the converging currents of Pittsburgh’s Monongahela and Allegheny. And contrary to the New York Clipper’s prediction, the match in Philadelphia would not be the last time Ward and Hamill would battle for the aquatic supremacy of America.

Following his victory on the Schuylkill, Hamill returned to Pittsburgh a conquering hero. He had, as noted by the Daily Missouri Republican, “carried the laurels from the brow of Joshua Ward.” Hamill would face off against Ward for the sculling championship of America three more times, twice in 1863 and once in 1864. Ward would win the first rematch at Poughkeepsie, New York, and Hamill would win the remaining two – first at Poughkeepsie and then at Pittsburgh.

Fathers and sons and old bachelors too,

Are sweating their brains to know what to do,

But ‘mid hope, fear, and good deal of craft,

They all seem bent on avoiding the draft.

– Star of the North (Bloomsburg, PA), March 9, 1864, 2.

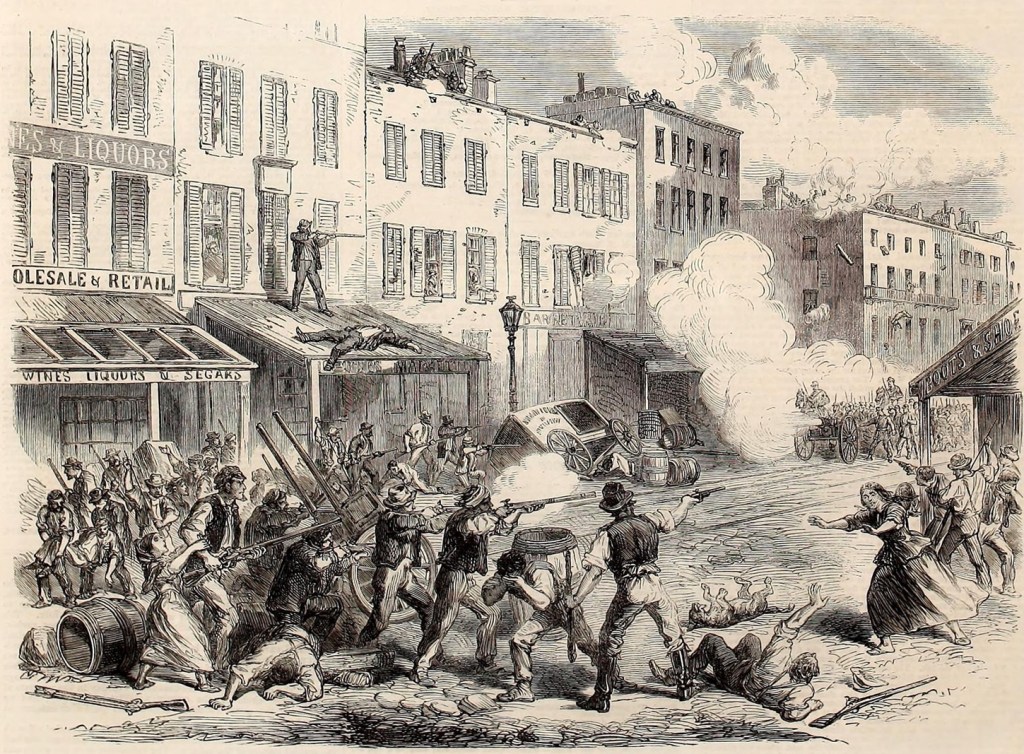

James Hamill and his brother John would receive a bit of national notoriety unrelated to rowing when on July 8, 1863, their names were coincidently drawn on the same day in Pittsburgh’s military draft lottery of the American Civil War. Pittsburgh reportedly had the honor of the first drawing under the federal Conscription Act of 1863. James was twenty-five, John was twenty-seven. However, neither brother ever saw military service. Both James and John took advantage of provisions in the law which allowed a Union Army draftee to either provide an acceptable substitute to take the draftee’s place or pay a $300 commutation fee, with either option relieving the draftee of his military obligation. Within the second week following the draft, James and John had each paid the commutation fee. Thus, the brothers were able to avoid military service, and James was able to continue to race and contend for prize money despite the nation being engulfed in war. The $300 fee, which was believed to be close to the average annual wage of a common laborer at the time, would be the equivalent of roughly $7,700 today. As might be expected, though, the substitution and commutation provisions were met with resentment, resistance, and even riots. The provisions were seen as unfair, especially by the poor, and reinforced their belief that the nation’s conflict was “a rich man’s war, and a poor man’s fight.”

In 1866, James Hamill, now the reigning sculling champion of America, crossed the Atlantic to pit his skills against Harry Kelley, the champion sculler of England. Unfortunately, Hamill was beaten in his two races with Kelley at Newcastle on the River Tyne. Nonetheless, Hamill was feted for his exemplary conduct and, moreover, was awarded with, among other tokens of appreciation, a gold watch inscribed with the following testimonial:

Presented to James Hamill, of Pittsburgh, aquatic champion of America,

as a mark of respect from his friends in Newcastle, England, for the

honorable and manly manner in which he conducted himself when residing

there, and for the honest and straightforward way in which he rowed two

races on the Tyne, July 11, 1866.

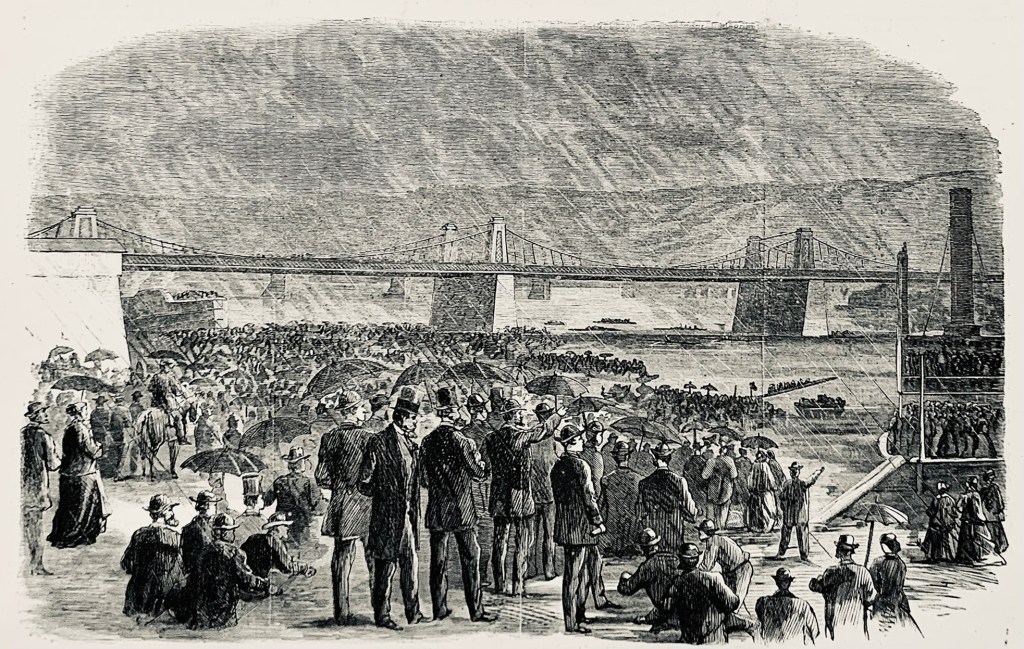

On May 21, 1867, Hamill briefly lost his American sculling title to Walter Brown of Portland, Maine. Brown had defeated Hamill in a five-mile race with a turn on Pittsburgh’s Monongahela River before at least 15,000 spectators on a day soaked by rain. Brown had lodged a claim of foul against Hamill following the race, and the next day Brown was declared the winner.

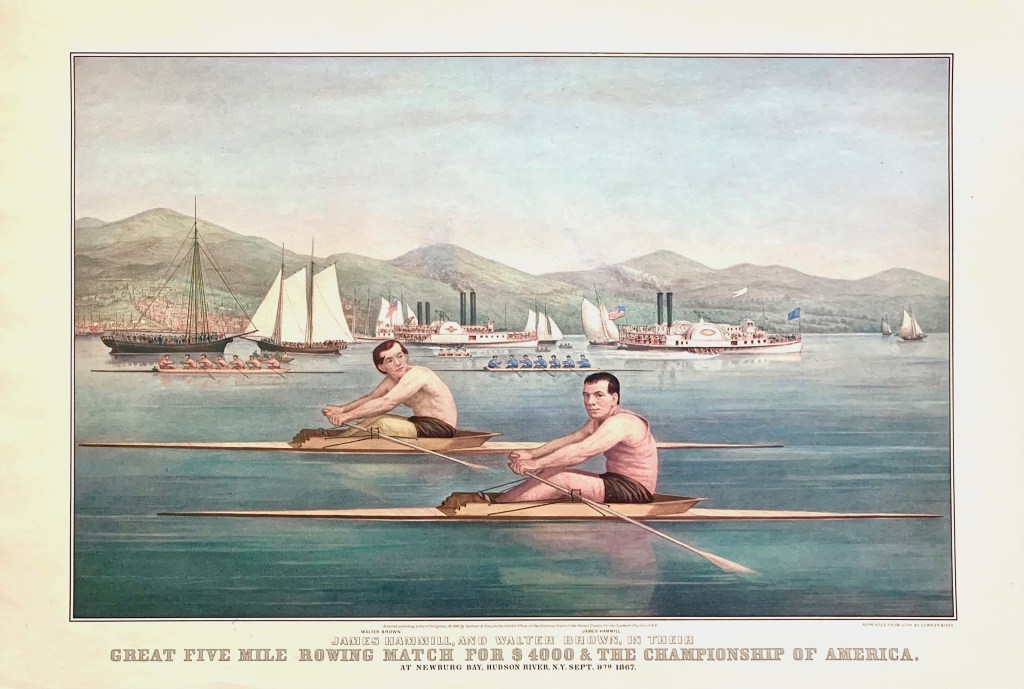

Hamill would go on to win two more American sculling championships, one in September of 1867 at Newburgh, New York, where he would regain the title from Walter Brown (who would go on to patent the sliding rowing seat), and one in June of 1868 against fellow Pittsburgher Henry Coulter at Philadelphia.

No one should attempt to go upon the water in a small boat without some knowledge of the art of swimming.

– The American Rowing Almanac and Oarsman’s Pocket Companion, 1874, 118.

During the races against Brown at Newburgh in 1867 and against Coulter at Philadelphia in 1868, Hamill had to be saved from drowning after colliding with each of his opponents. At Newburgh, as Hamill and Brown were turning the single stake boat during their five-mile race, the bow of Brown’s boat pierced the thin wooden hull of Hamill’s boat at nearly a right angle, causing it to immediately fill with water and sink. Hamill had to be rescued from the Hudson River, finding refuge in a boat nearby. The non-swimming Hamill had insisted that the articles of agreement for the race include a “fair day” clause, whereby he could postpone the race if he considered the water to be too rough. It was said that Hamill had “no little dread of being upset or swamped at some unlucky moment.”

In the Newburgh race, which had initially been postponed due to bad weather, it was determined that Brown was at fault for the mishap, even though he had extricated his boat following the collision with Hamill and finished the course. Hamill, therefore, was declared the winner. The race (pre-collision) was commemorated in a Currier & Ives color lithograph titled Great Five Mile Rowing Match for $4000 and the Championship of America (1867).

On August 19, 1869, Hamill faced defeat at the hands of Henry Coulter on Pittsburgh’s Monongahela River. The loss prompted the Pittsburgh Commercial to conclude that Hamill’s racing days were over as far as competition with his more youthful rivals such as Coulter and Brown was concerned. The comment proved prophetic. The defeat was Hamill’s last major professional boat race.

In the summer of 1873, Yale University engaged the services of Hamill to train its freshman six-oared crew in preparation for the Collegiate Regatta scheduled for that July in Springfield, Massachusetts. No longer an active rower, Hamill was now considered “corpulent.” He was described as weighing about 200 pounds and looking as though “he would sink a boat if he should get into it.” Regardless of his weight, the Hamill-coached Yale freshman crew, with an average weight of 148 pounds, won their three-mile freshman race against Amherst College and Harvard University.

Following his departure from boat racing, Hamill operated the Constitution Saloon in Downtown Pittsburgh, from which business he subsequently retired to accept a position in the Pittsburgh Fire Department of which his brother John was Assistant Chief Engineer. In his post-rowing days, James, according to the Daily Albany (NY) Argus, had “not led an abstemious life by any means,” and on January 10, 1876, following a brief illness, at the young age of thirty-eight he died at his Pittsburgh residence. The Argus asserted that his self-indulgent lifestyle was the likely cause of his sudden death. The Cincinnati Daily Gazette went so far as to claim Hamill’s early death was another illustration of the “well-known fact that excessive cultivation of muscularity was unfavorable to longevity.” The self-indulgent lifestyle assertion by the Argus would be supported by the official death report which listed alcoholism as the primary cause of death, with cerebral meningitis as the secondary cause.

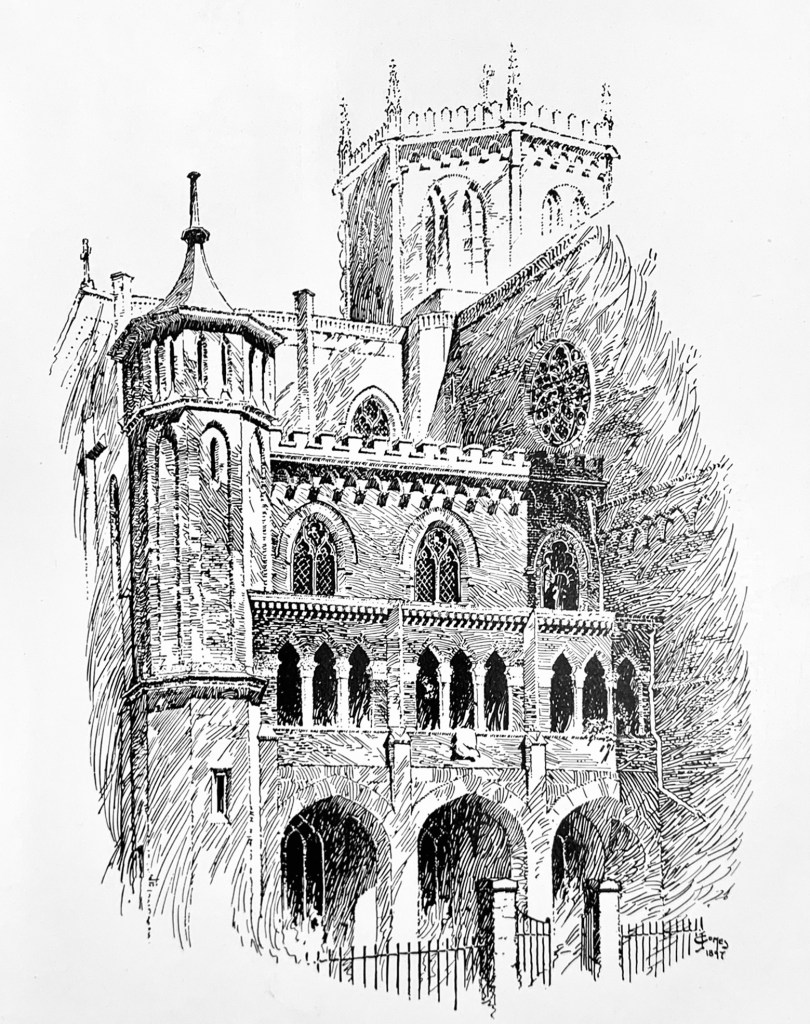

Hamill’s funeral was held on January 12 at St. Paul’s Cathedral, then located in Downtown Pittsburgh. Pallbearers included fellow Pittsburghers Eph Morris and William Scharff who would each follow in Hamill’s footsteps and lay claim to the American sculling crown. Hamill was buried at St. Mary Catholic Cemetery in Pittsburgh’s Lawrenceville neighborhood. One of his many obituaries described him as having a cheerful disposition and a rollicking good humor which made him a favorite with everybody who knew him.

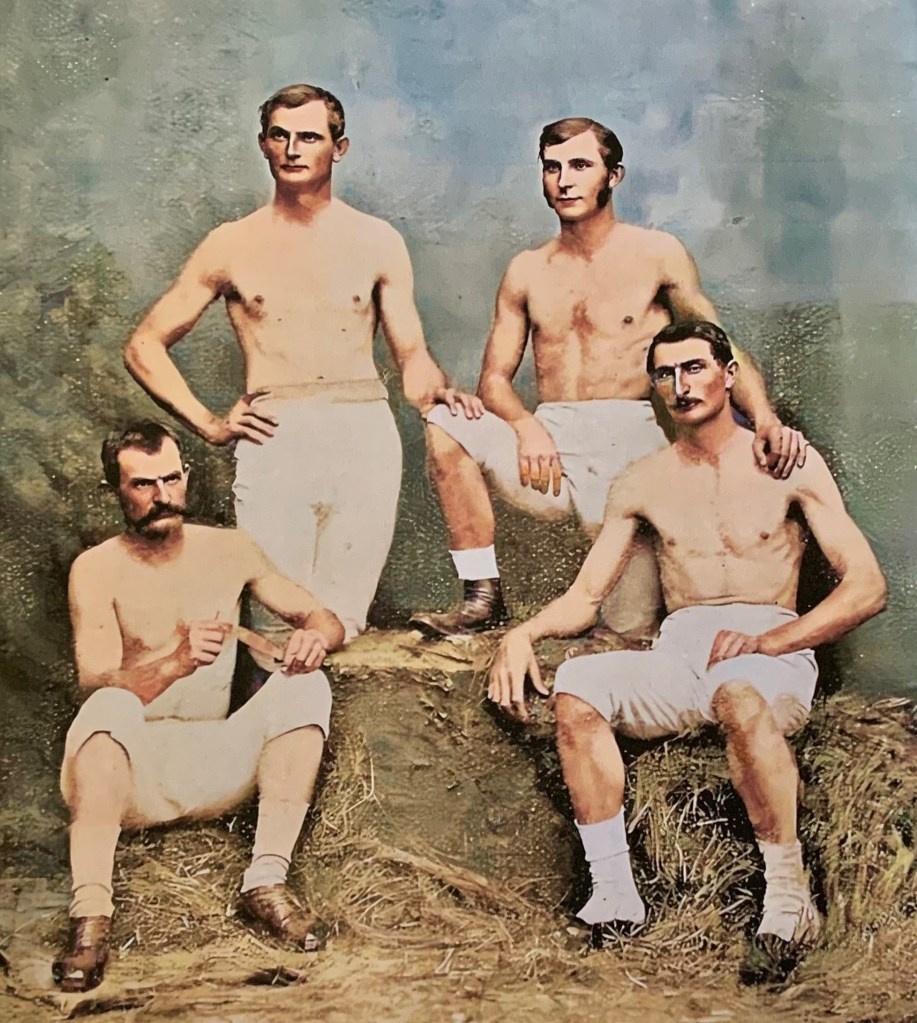

With Hamill’s six national sculling championship wins, he was the best professional oarsman in America. Other Pittsburgh oarsmen and oarswomen would gain fame in the latter decades of the nineteenth century and carry on the city’s sculling supremacy. Evan “Eph” Morris, John Teemer, William Scharff, Pat Luther, and Henry Coulter would each vie for the American sculling championship, with Scharff, Morris, and Teemer each winning the crown at least once.

And two sixteen-year-old working-class Pittsburgh girls, Lottie McAlice and Maggie Lew, would make history in 1870 as the first female rowers in America to compete against each other in a single-sculls race, with McAlice emerging victorious. News of her win would reverberate across the United States and beyond. Today she is recognized in the city by an annual sculling competition that bears her name. Therefore, with such Pittsburgh rowing dominance, the city can arguably claim the title of Sculling Capital of America for the twenty-five-year span from 1862 through 1887.

Lovely Lottie

By Edward H. Jones © 2025

Lovely Lottie raced her boat

upon the River Mon.

In doing so she earned a spot

in rowing’s pantheon.

Though Lottie never raced again,

her legacy is vested.

She showed what female pluck can do

when womanhood is tested.

James “Jimmy” Hamill’s life was full of contradictions. He excelled at the sport of rowing that favors a physique that’s long and lean, yet he was described as “short” and “chunky,” with the “physique of a prize fighter” and, according to one account, “squat.” At a time when the nation’s major rowing centers were located along the eastern seaboard, Hamill hailed from the inland “western” city of Pittsburgh. Hamill never attended college, yet he nonetheless successfully coached rowing at Yale University. And although he gained fame for his prowess on the water, he never learned how to swim. He was a Union Army draftee during the American Civil War, but he never saw military service and would continue to race as the war raged on. Against all odds, and despite all the contradictions, Hamill rose to become America’s best professional oarsman, and yet his occupational designation of “glass-blower” remained with him even upon death as noted on his death certificate.

Despite all of James Hamill’s accomplishments and all the fame and prestige Pittsburgh’s native son bestowed upon his hometown, his family’s burial plot at St. Mary Cemetery has no monument, tombstone, plaque, or other marker indicating that anyone is buried there, let alone America’s greatest professional oarsman. In the story of Hamill’s short life of contradictions, this is perhaps the greatest contradiction of all.

“Pittsburgh’s Jimmy Hamill – Part II: Horsing Around” will be published tomorrow.