Three races, two oarsmen, and one sculling rivalry mired in controversy

17 September 2025

By Edward H. Jones

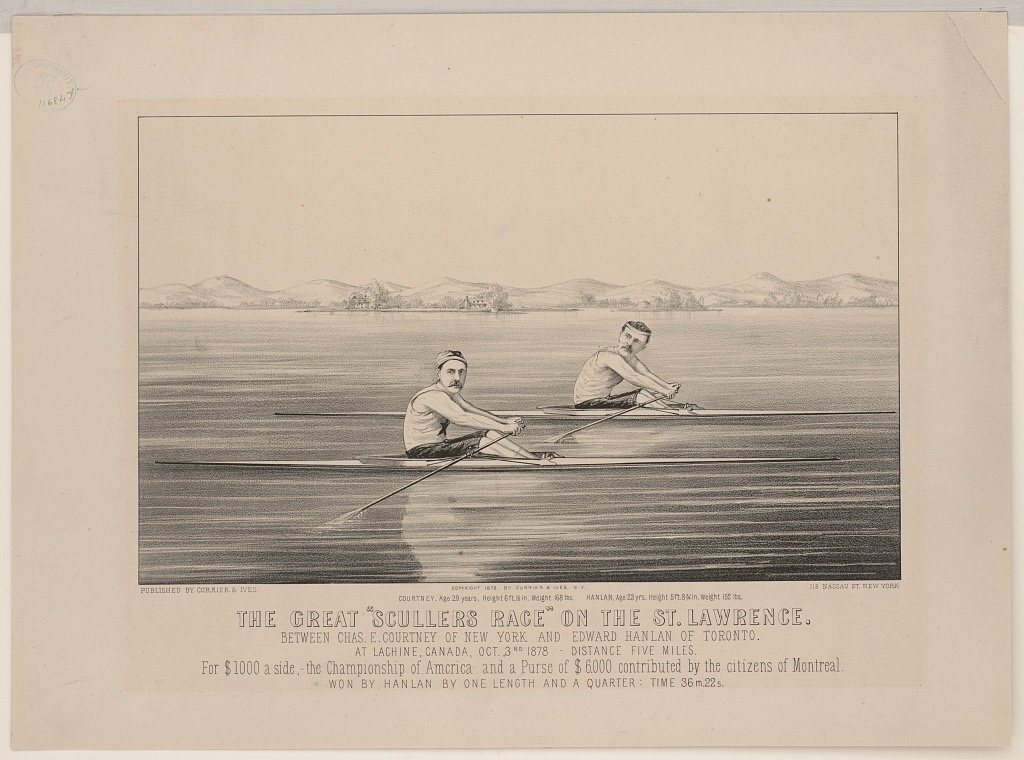

In the late afternoon of October 3, 1878, Canadian sculling champion Edward “Ned” Hanlan from Toronto and American sculling champion Charles E. Courtney from Union Springs, New York, competed in a five-mile sculling race with a turn on the St. Lawrence River at the Canadian town of Lachine, today part of Montreal. In this race with a turn, each rower had to row two-and-a-half miles to a buoy, turn (pivot) around the buoy, and row back to the starting point. In addition to providing a challenge to the rowers, races with turns, which were popular the time, allowed the spectators to see both the start and the finish of a race. At Lachine, Hanlan and Courtney were competing for a stake of $1,000 aside, meaning that the financial backers of each side (each rower) put up $1,000, with the winner taking the entire $2,000 to be shared with his backers. In addition, the citizens of Montreal put up a purse of $6,000 to be awarded to the winner as assurance that the race would not be called off. Thus, the winner would walk (row) away with $8,000, worth over $250,000 in today’s dollars. As Hanlan was Canadian and Courtney was American, the race was naturally seen as contest for the sculling supremacy of North America.

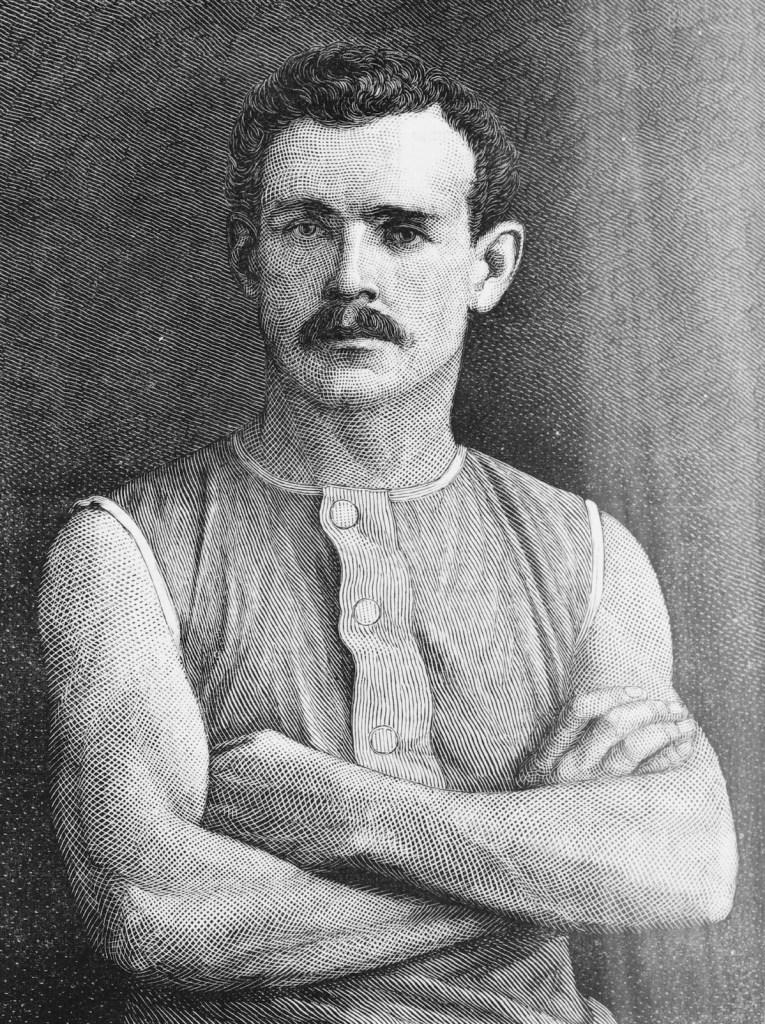

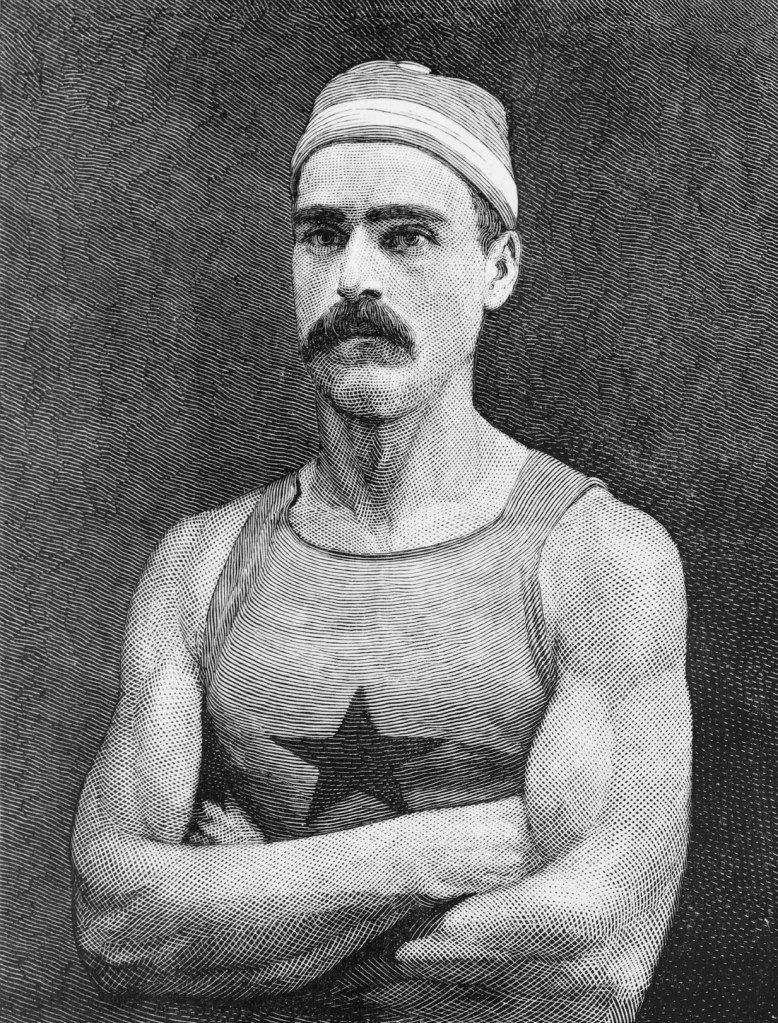

Hanlan, who was known as “The Boy in Blue,” was the first to make his appearance on the water. He wore his trademark blue attire – blue jersey with red trim, blue trunks, and a red handkerchief around his head. Courtney then followed, clad in a white jersey with a blue star emblazoned on his chest, white trunks, and a blue sculler’s cap. Hanlan was described as small, lithe but sinewy, with a good-natured smile upon his face and fair, clean, light skin. Courtney, in comparison, was described as a hearty, generous-looking giant, “dark and tawney as an aborigine,” with muscles “standing out like ropes.” The race was thus seen as a trial of skill and style against muscle and weight.

Six days after the race, the Montreal Gazette published a poem by a Canadian named J. Lockie Wilson. The rhyming poem describes the race at Lachine and reveals the eventual winner. The poem interestingly refers to Hanlan as “the Beaver” (a national symbol of Canada) and Courtney as “the Eagle” (a national symbol of the United States). The poem accordingly was given the alliterative title of “The Beaver and the Bird.” Below is the poem, complete with the outdated language and obscure references of the era:

The Beaver and the Bird

By J. Lockie Wilson

The gala morn; the autumn day

Rose o’er St. Lawrence’s wat’ry way,

Which calm did seem, yea almost dead,

Just at Lachine’s rough rugged head,

Here crowds of every age and place

Have gathered to the champion race.

Now in their boats sit side by side

The “Eagle’s” hope and “Beaver’s” pride.

The word is given, away they go

Over the waters swift they row.

The dull quick plashing of the oar

Is heard along the sounding shore.

As their light shells their course pursue

Towards Sol’s lone couch with crimson’s hue,

Now to the turning buoy they come;

Men cease to breathe, each voice is dumb.

Hanlan’s ahead! “The boy in blue”

Has turned it first; ‘tis true! ‘tis true!

Now homeward bound the scullers glide,

Neck and neck o’er the wave they ride,

Crowds call upon their favorite man,

And cheer him on as best they can.

“Go for him, Charlie!” “Pull hard, Ned!”

A goodly fortune’s on your head.

Excitement now grows on apace,

Is it Courtney’s! or Hanlan’s race!

One mighty plunge the “Beaver” makes

Fair Canada has won the stakes.

A rousing cheer rends air and sky,

And Yankees heave a ghastly sigh.

Now gallant “Eagle,” fold thy wing,

For Hanlan is the sculler’s king;

Loud let us make the welkin ring,

And loud his kingly praises sing:

Champion of the world is he,

And may he ever bear the gree.

As down tim’s stream the scullers go,

Upward and onward may they row,

Steer with rudder and pull with oar

Until they reach the better shore.

And when their latest race is run,

Meet in bright realms beyond the sun.

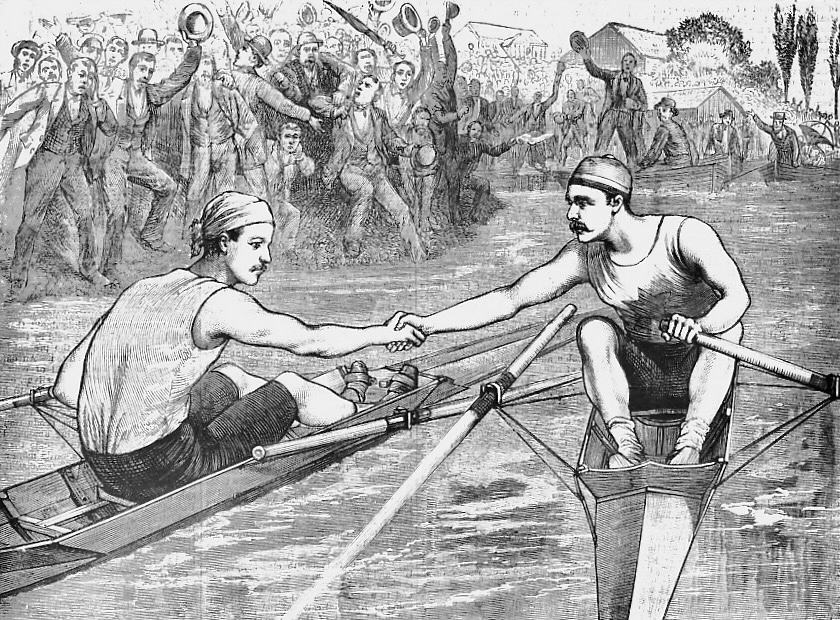

At the finish, the victorious Hanlan rowed alongside Courtney and the two men reportedly “warmly” shook hands amid the loud cheers of the crowd. It was estimated that more than 10,000 spectators witnessed the race. The win no doubt inspired Mr. Wilson to write the poem celebrating his fellow countryman’s triumph. The designated referee declared the contest the most magnificent race he had ever seen. But even before the two contestants had crossed the finish line, rumors began to spread that Courtney had “sold” the race.

As the suspicion that Courtney had sold the race grew to a general belief, the Kingston (Ont.) Daily News reprinted the following item from a New York Tribune special Montreal dispatch:

“There were some things about the race which certainly give colour to suspicion, such as Courtney’s poor rowing in the last mile, when his stroke never exceed thirty-two, and the very crooked steering of the men near the finish, Courtney getting very much into Hanlan’s water, and [Courtney] having to stop short just before reaching the line to avoid a foul. At any rate, whether it is true or not, many people hold the opinion very firmly, and the result has already ruined Courtney’s reputation, and will do much to throw professional rowing into disfavor.”

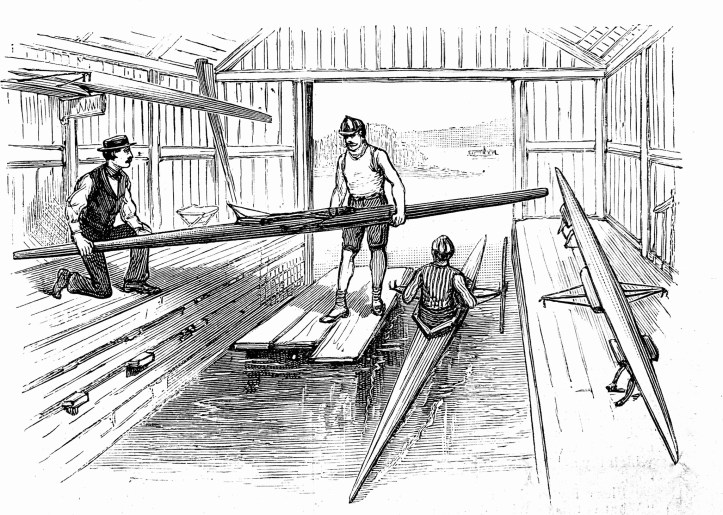

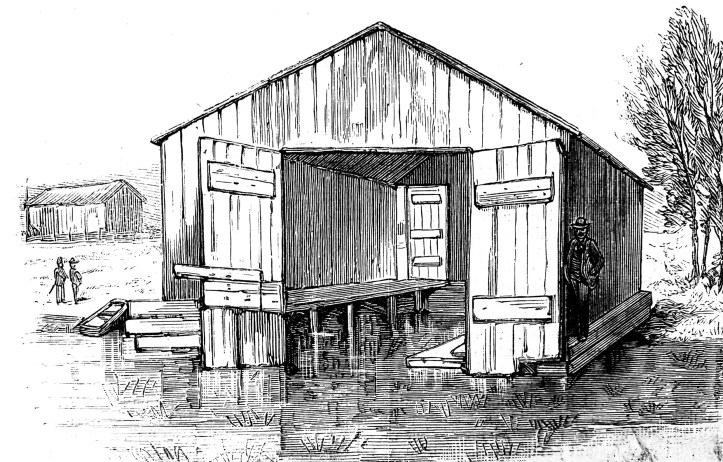

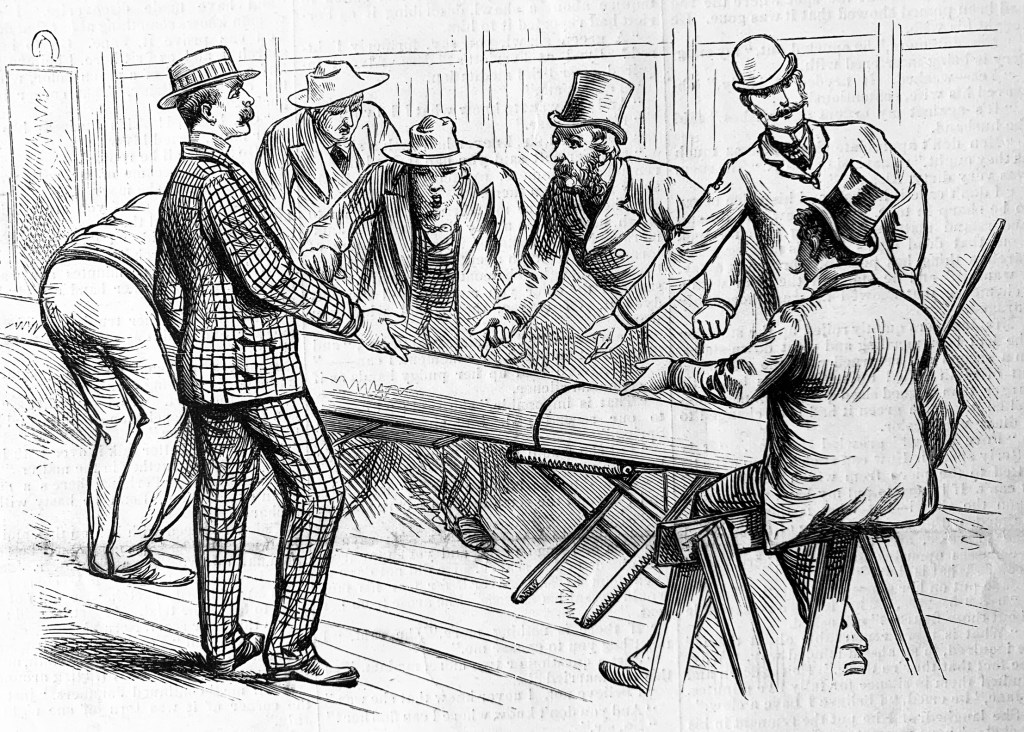

Hanlan and Courtney would arrange for two more head-to-head sculling matches. One was at Chautauqua Lake in western New York state near the town of Mayville. There the two boatmen were scheduled to row a five-mile race with a turn on October 16, 1879, for a prize of $6,000. However, on the morning of the big race, it was discovered that Courtney’s prized racing shells had mysteriously been sawed almost in half while being stored in the Courtney boathouse. Accusations abounded, and the race never took place. The whole incident was described by one account as a “miserable farce.” Neither Hanlan nor Courtney was immune from suspicion. Newspapers around the country took aim at both oarsmen with headlines such a “Hanlan’s Scheme” and Courtney’s Cutter.” The press mocked both men with digs such as “Both Hanlan and Courtney are row-bust persons [emphasis added].” It had even been suggested that Courtney had arranged to have his own boats cut to avoid having to compete against Hanlan. Even Courtney’s friend and fellow professional oarsman Frenchy Johnson, who was at Chautauqua serving as Courtney’s trainer and assistant, got caught up in the web of accusations. The non-race became known as the “Chautauqua Lake Fizzle.” The New York Herald called the incident “the most miserable end to what promised to be a notable race and will do great harm to boat racing for some years to come.”The comment would prove prophetic, as the “Great Race Not Rowed” at Chautauqua would help sound the death knell for professional rowing in America. As The Herald acknowledged — “amateur boating men confidently boasted that the whole affair had given professional rowing its death blow.” To this day, the mystery of the boat-cutting incident has never been solved.

Fizzle at Chautauqua Lake

By Edward H. Jones © 2025

The Hanlan-Courtney race did break

The hearts of folks who bet a stake.

What then did make their wallets ache?

The “Fizzle” at Chautauqua Lake.

Was Charles Courtney “on the take”?

Did Edward Hanlan “cut C.’s cake”?

What caused the public’s trust to shake?

The “Fizzle” at Chautauqua Lake.

Particulars were quite opaque,

But both men did their fans forsake.

A scandal followed in their wake –

The “Fizzle” at Chautauqua Lake.

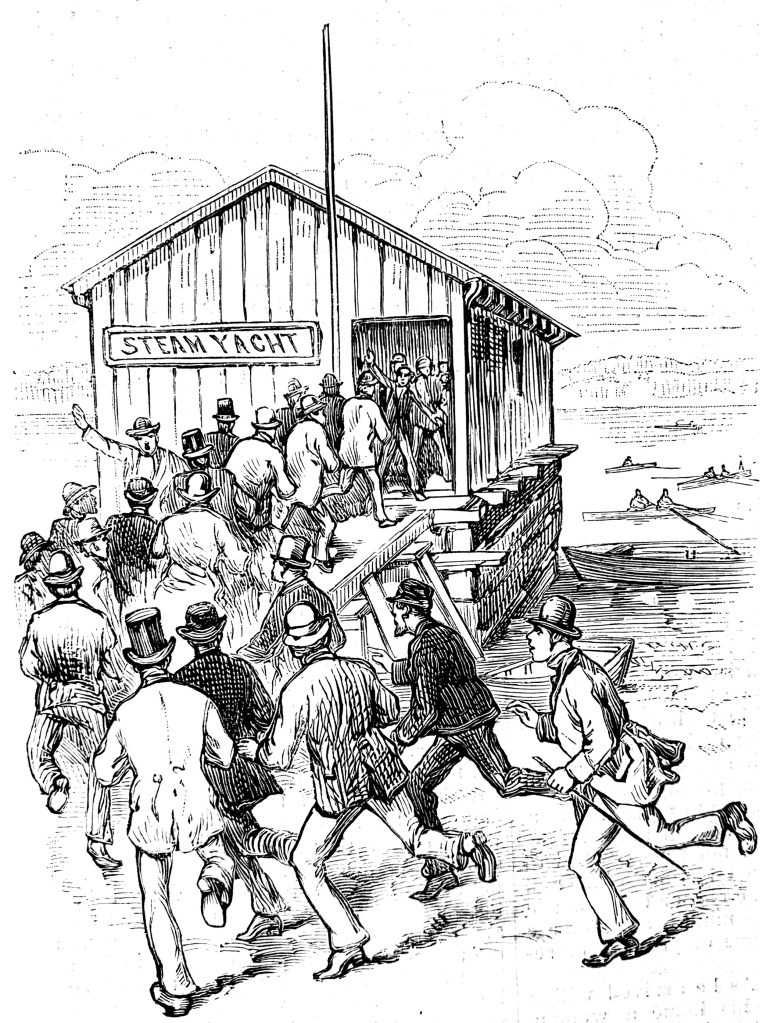

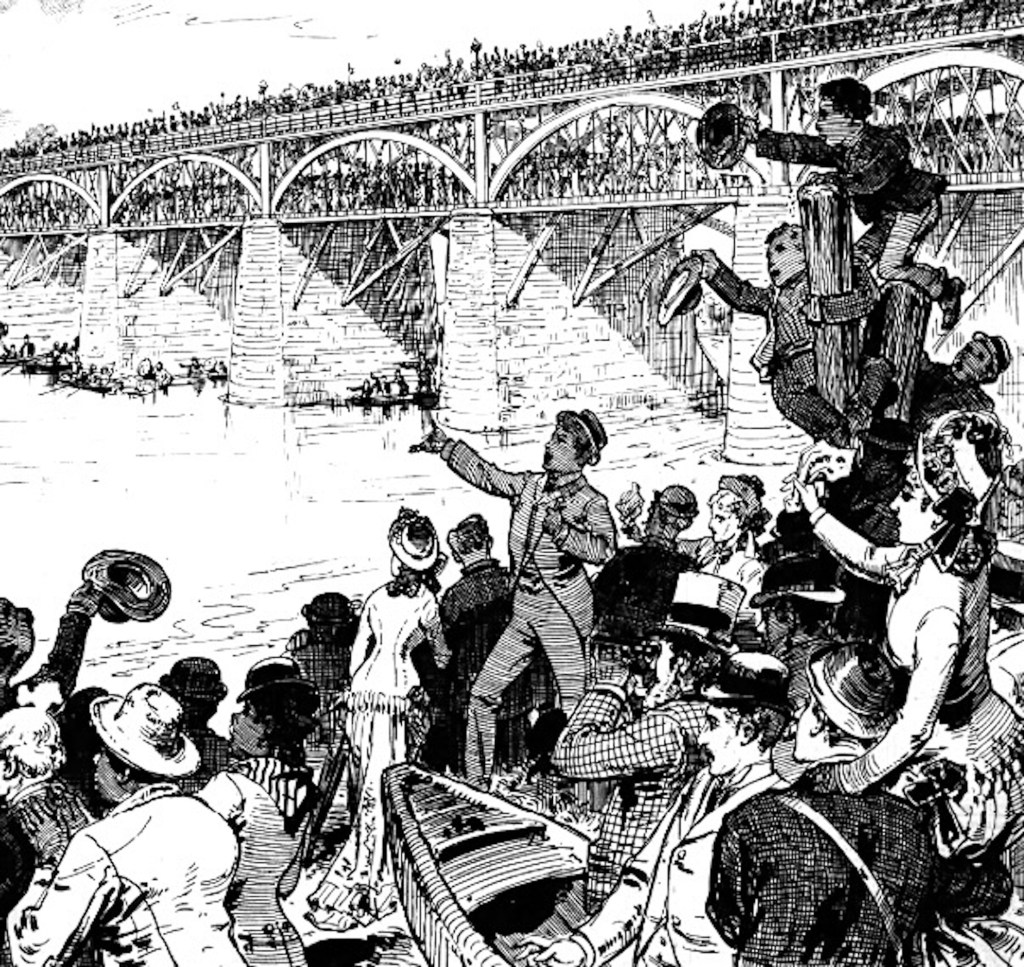

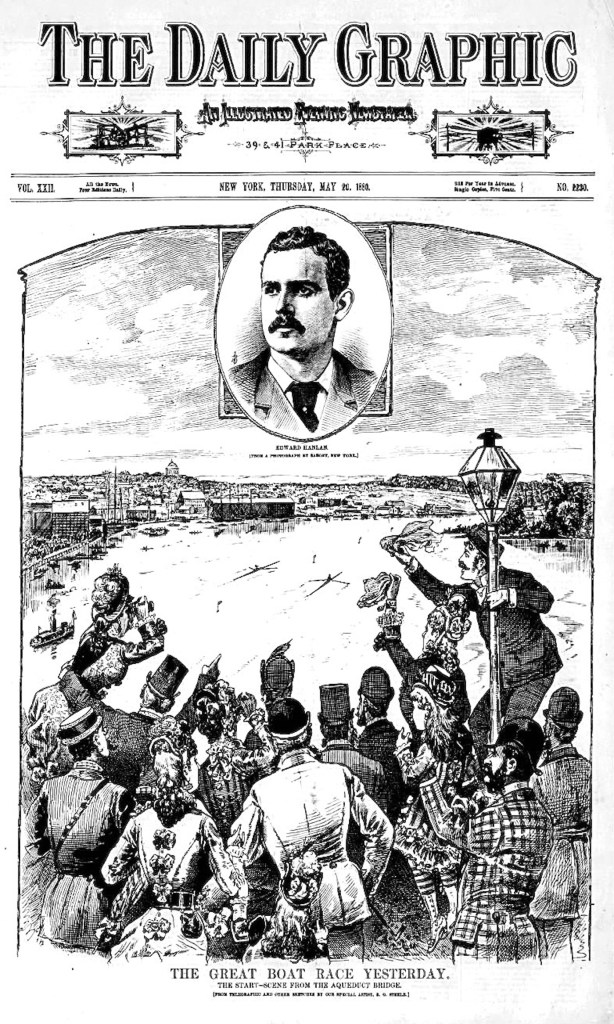

The third and final sculling contest between Hanlan and Courtney was on May 19, 1880. The men were scheduled to row a five-mile race with a turn on the Potomac River at Washington, D.C., for a prize of $6,000, calculated to be worth over $190,000 today. Interest in the race was so high that on race day the city was reportedly deserted. It was estimated by one account that no fewer than 75,000 persons were out on the riverbanks to witness the contest.

Across the river, at the head of the course, stretched the acqueduct [sic] bridge, loaded with men and women, almost to the limit of safety. On the Virginia side lay a line of large schooners, with people covering the decks and hanging to the rigging, and in front of those lay hundreds of small craft. . . . The towers of the new building of the Georgetown College commanded the whole scene, and below lay the ancient warehouses and dwellings of the town, covered with people, who looked down upon long lines of newly-erected seats and upon schooners weighed down with human freight.

– The New York Times, May 20, 1880, 1.

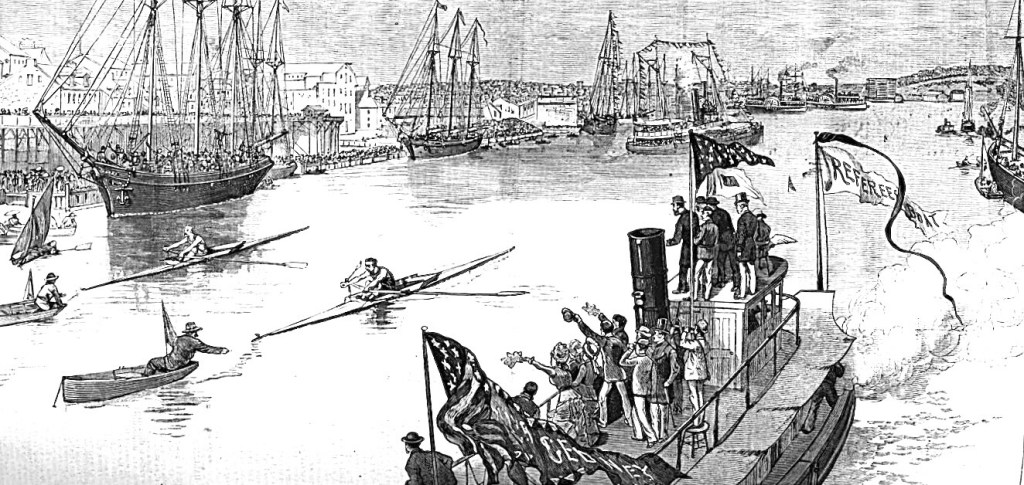

Government employees were permitted to leave work early so they could have plenty of time to get to the scene and secure favorable points for looking down on the racecourse. The men in both houses of Congress were compelled to take an early recess because they lacked a quorum needed to conduct legislative business, as some of their brethren had decided to focus their attention on racing instead of rulemaking. President Rutherford B. Hayes and members of his cabinet observed the race from the deck of the referee’s boat. A headline in The New York Times the following day told the whole story of the race:

A FARCE ON THE POTOMAC

Courtney Gives Away The Race To Hanlan

A Good Start But A Miserable Ending – Courtney Gives Up After Rowing A Short Distance, Hanlan Pulls Over The Course Alone – A Disgusted Medicine Man And Over Fifty Thousand Disappointed People.

The racecourse began just down-river of what had then been the Washington Aqueduct Bridge near today’s Francis Scott Key Memorial Bridge. The course then went in an east-southeasterly direction for half a mile, then angled south-southeasterly along past what is now Roosevelt Island (then Analostan Island) and continuing straight for two miles to the turning stake-boats close to the river’s Virginia shoreline and just above Long (Railroad) Bridge near today’s I-395 Bridge, and then back up-river retracing the course to the starting point for a total of five miles. A coin toss determined the lane assignments. Hanlan had won the toss, and upon the advice of his assistants chose to row the Virginia side of the course, leaving Courtney to row the Washington side.

At 6:08 P.M., the gun sounded for the start. According to The New York Times, the race began well, but after Courtney had pulled only a few strokes “the life seemed to leave his arm[s].” At about the two-mile mark, Courtney pulled up and stopped rowing altogether while Hanlan, who was in the lead, continued to complete the course and was declared the eventual winner. As for Courtney’s nonperformance, the night before the race his friends, relatives, and attendants “assiduously” spread the news that he was seriously ill. They claimed he had suffered from the heat during his morning row and had returned to his hotel and had taken to his bed. Discouraging statements continued to be freely made by these persons who talked vaguely about sunstroke and the possibility of Courtney not rowing on race-day. However, betting men weren’t buying the illness story, and the general belief was that it had been concocted for the sole purpose of influencing the betting.

There were theories proffered by boating men to account for Courtney’s nonperformance. None of the theories involved an illness. Some contended that Courtney’s real trouble was “ineradicable cowardice.” Others believed that his behavior was in accordance with terms of some “secret agreement” to “sell” the race. The St. John (NB) Daily News, citing the Philadelphia Bulletin, quipped that Courtney used to be called “the Union Springs Sculler,” but after the fiasco on the Potomac “he is now to be known as ‘the great American Scull cur’ [emphasis added].” The Ottawa Daily Citizen reported that “everybody [in Washington] is cursing Courtney,” and his race “breakdown” has ruined him as a boating man. Worse yet, The Daily Graphic reported that among the prize-fighting crowd, there was even talk of “tarring and feathering” Courtney which fortunately was never carried out.

There was a universal feeling among the hundred thousand spectators that they had been atrociously victimized. The feeling is general that the race was sold out, and Courtney is the subject of furious denunciations. As an oarsman, he is dead, with his reputation damned. . . . Everyone seems to feel that the Utica (Union) Springs oarsman was chiefly to blame for the dishonorable fiasco, if such it was, and it is safe to say that his life would not have been worth a minute’s purchase if the crowd could have laid hands upon him.

– The Daily Register (Wheeling West Virginia), May 20, 1880, 1.

As for the Disgusted Medicine Man, he was a gentleman who had put up stake money and was said to have been greatly dissatisfied because the newspapers had not given his patent medicine the free advertising which he thought he had a right to expect.

The Times concluded that whatever the cause of the race-day nonperformance by Courtney, there could be no doubt that, to the people of Washington, “the peculiarities of professional boating [had] been revealed in a very disagreeable manner,” and that they would not be eagerly seeking a match on the Potomac River racecourse for some time to come.

The disgraceful Hanlan-Courtney fiasco of Wednesday will probably end the career of the latter in this country at least. For years the public have allowed themselves to be deluded into the belief that at the proper time Courtney would shine forth as a brilliant star in the galaxy of renowned oarsmen. On three separate occasions this proper time has seemed to have arrived, but, for some unexplainable reason, the great rowist has failed to respond with that alacrity necessary to a maintenance of his pretensions. In the future, the public will refrain from venturing its faith, much less its money, upon one who has proved himself to be but a windy braggart, alike lacking in honor and courage.

– Chicago Daily Telegraph, May 21, 1880, 2.

The “Loss at Lachine,” the “Chautauqua Lake Fizzle,” and what I’m calling the “Potomac River Pullup” all did little to enhance Courtney’s reputation as a professional sculler. The fallout from these three scandal-ridden events would haunt Courtney for the rest of his professional rowing career. Author and rowing historian William Lanouette in his book The Triumph of the Amateurs: The Rise, Ruin, and Banishment of Professional Rowing in the Gilded Age (2021), and in the chapter he contributed to The Greatest Rowing Stories Ever Told (2023), describes this triumvirate of boating encounters as “Three Races, Three Disgraces.”

Although it was “the Beaver” who emerged victorious in the end, clipping “the Eagle’s” wings and gnawing the great raptor’s scull blades down to the shafts, the triumph could not make up for the fact the American public was growing weary of the scandal and dishonesty surrounding professional rowing. And although Courtney bore the brunt of the vitriol spewed by the public, Hanlan was not above reproach. The Wheeling Daily Register noted that during all the excitement surrounding the Potomac River race, it was remarkable that “the men who anathemized Courtney for selling, had no word of reproof of Hanlan for buying.” The following anonymous poem published in the National Republican (Washington, D.C.) the day after the Potomac race expressed the feelings of the supporters of Courtney (“C.”) who, incidentally, was incorrectly depicted in blue racing attire (his shirt was white) on widely circulated cards purporting to show the race-day “colors” of the two competitors:

A Long Way After Tennyson

Broke! Broke! Broke!

On thy sculls, O, blue, blue C.;

I would that my lips could find

New cuss-words to fling at thee.

Oh! Well for the Hanlan sports

Who offered the odds to me!

Oh! Well for the pool-seller glib

Who took in my seven to three!

Broke! Broke! Broke!

Or busted, whatever it be,

The touch of my dear greenbacks

Will never come back to me.

Both Courtney and Hanlan would survive their three sculling scandals. To paraphrase a quote allegedly attributed to American humorist Mark Twain about himself, “reports of my [Courtney’s] death [as a professional oarsman] have been greatly exaggerated.” Despite their racing controversies, Hanlan and Courtney would continue to row professionally, and die-hard racing fans would continue to be drawn to their exploits. Upon their retirement as professional oarsmen, both men would enter the ranks of college coaching with Hanlan coaching rowing at the University of Toronto and then at Columbia University (NYC) and Courtney at Cornell University (Ithaca, NY). Although these two scullers had successfully survived the public’s scorn, they unfortunately set in motion events that would bring about the eventual demise of professional rowing in America.

Click on the link below for a comment from Tom Daley.

https://heartheboatsing.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/the-beaver-and-the-bird-comment-2.pdf

I am glad Mr. Daley found my article “fascinating and entertaining,” and I thank him for his comments. I am always happy to receive feedback on my articles posted on HTBS.

It was never my intent to tear down such a towering figure in American rowing as Charles E. Courtney. I started out merely intending to present to HTBS readers a nineteenth-century poem related to rowing. To put the poem into context, I felt I needed to tell the story of the corresponding race at Lachine, Canada. I then felt compelled to complete the story of the Hanlan-Courtney sculling rivalry and the public’s increasingly negative attitude toward professional rowing by telling the story of the races that were scheduled to be rowed on Lake Chautauqua and the Potomac River. Further, because I had come across poems for the Lachine and Potomac River races, I felt that I needed to round things out and compose a poem for the Lake Chautauqua race that never took place. Therefore, what started out as a simple desire to present a nineteenth-century sculling poem ended up being a 3,200-word article on the much-discussed Hanlan-Courtney sculling rivalry.

I should note that in my article about Courtney’s friend, protege, and occasional sculling competitor Frenchy Johnson – “An Oarsman and a Gentleman: Frenchy Johnson Steps Forth” (HTBS, May 9, 2025) – I wrote the following: “After a career as a professional sculler, Courtney became an esteemed and successful rowing coach at Cornell.” In conclusion, I duly note and concur with Mr. Daley’s comments.

Edward H. Jones