16 September 2025

By Ben Lowings*

(text and drawings)

Walking one afternoon down to the river, my thoughts were not about the team session of rowing, but about English’s hefty vocabulary. Words for almost everything. For instance, ‘petrichor’: the smell of hot tarmac after rain sweeps the road.

Most rowing craft sound a ‘clank’: sleeve-on-gate at the blade-catch, louder at the release. It shocks gunwale, vibrates topnut, shakes boat, stops you like a lever thrown over a cog in a mighty piece of machinery.

What is this sound called?

I’m at a loss. Tone and register differ in every boat I have rowed. This is owing to the length of the loom. What it is made of. What the boat is made of. How wide the oarlocks’ ‘soundbox’ is, in terms of the space between the saxboards.

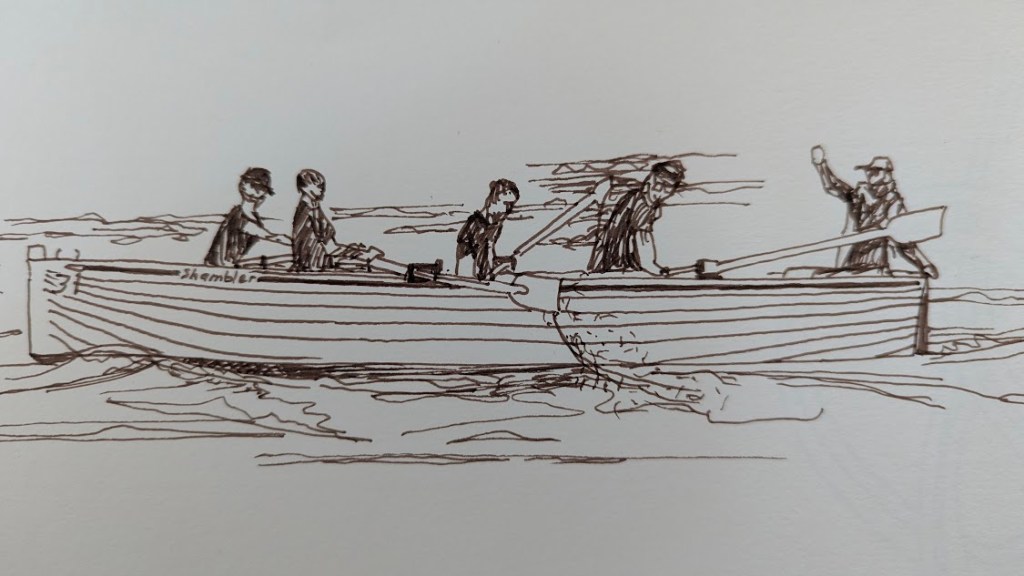

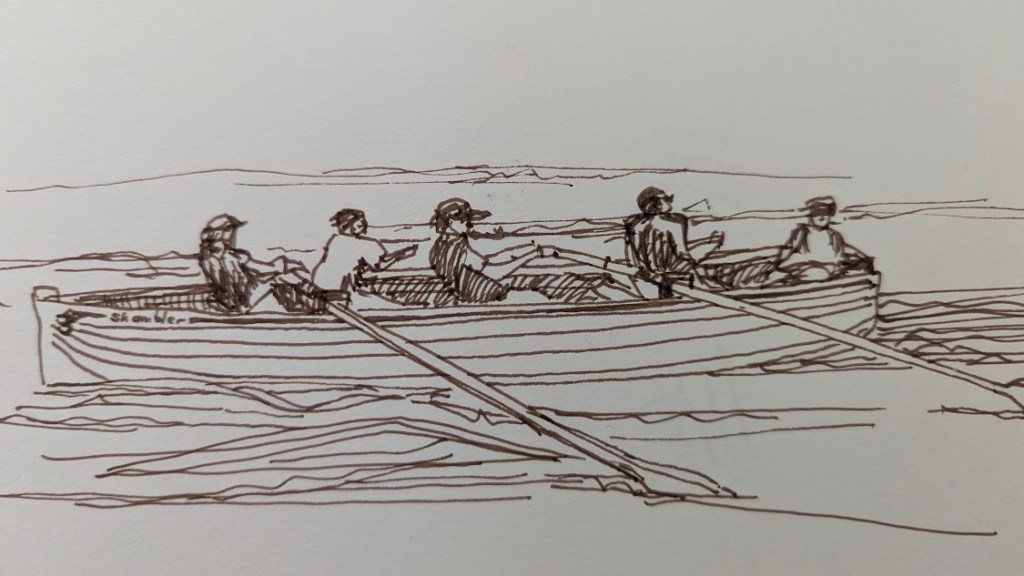

Down at the pontoon, we sit in. I ponder further: a five-metre GRP seiner, white with royal blue trim. Stern-loaded. Two sweeps on each side. A crew making homage to the commercial fishing families of a different era. They made a living from rowing craft like this. Fashioned from planks of larch and elm, clinkered together. Their quarry was Exe salmon. The fish would be snared in cross-river nets laid out over transoms like this one; the bounty heaved in over gunwales such as these. Never would their fish finish their Atlantic journey to spawn in headwaters in Somerset, 50 miles inland. Salmon-fishing is no longer sustained here; its long decline capped by a ban brought in before Covid.

The boat is superbly adapted to rowing. She tracks well, even low in the water with five adults. We are way less of a cargo than a mound of net plus fish. Those professionals would have outraced us, once-a-week club-rowers, for sure. But we do not have a drunken spider tendency. Good coxing evens out the raggedness. I rush the stroke. I could do with a better sense of rhythm. A one-man hammer buries the spoon six inches below the others. A crab is less likely, thankfully, than a strike on the sand. Devon clay is something between brown and pink; the sun-faded crimson of a pirate’s neckerchief, or a high, old sail.

This is not flat water for counting up puddles-like-shoelace-eyelets. We swerve between white yachts parked between estuary slimelines. A drive together has us barely holding against the flow. There is no thought of upping the rate and feathering, the better to churn the boat over the long brushstrokes of tide.

Evening ticks on.

The river’s sheen becomes yet more lustrous. On the recovery phase our noses catch that sea-reek of ozone; sailing weed and the wet undersides of dried pebbles. Russet wash looms and tumbles to the riverbank as oatmeal in evening sunlight. The sea beyond is a brilliantine wallpaper. The white belly of a fish being hunted by another skims the surface like a stone and vanishes. A cormorant on a mooring buoy spreads his devil wings.

We are a seine boat but Salar the Salmon is safe. We will cast no net. Then something connoting heaviness strikes me. The sound the oar makes in the oarlock, wood on wood…

It’s not a ‘clunk’…

It’s the ghostly sound of the Priest. This was what the fishermen called the wooden club they used. The salmon’s life would be struck out when this club knocked its head against the gunwale.

‘Thunk!’

Or is it? To nail the word correctly would be to extinguish its spell, I feel, and row on: this sport is conducive to philosophy.

*Ben Lowings is a journalist contributing to a few sailing magazines. However, Ben writes that he “spend more time rowing a replica salmon-fishing seine boat in the River Exe, than I do cavorting around sailing yachts”. He is a member of the Starcross Fishing and Cruising Club (SFCC), which is a community based sports and leisure boating club located on the western shores of the Exe Estuary in Starcross, just south of Exeter in Devon.