19 July 2025

By Edward H. Jones

In Part I, Joseph Trigg displayed his athletic prowess as a collegiate rower and football player. In Part II, Trigg goes off to fight in WWI, receives a medical degree, becomes a ringside boxing judge, and earns recognition as a caring and compassionate doctor.

From Officer to Obstetrician

On June 18, 1917, Joseph Trigg would trade his sweep oar for a rifle when he became part of an inaugural class of 1,250 African American men who would begin instruction at a U.S. Army training camp officially known as “The Fort Des Moines Training Camp for Colored Officers” located at Des Moines, Iowa. Building a military force drawn from all segments of society, a concept known as universal military service, was a hotly debated topic in Congress. There were individuals who simply were against African Americans serving in the military in any capacity whatsoever. But after persistent pressure from the Black press and organizations such as the recently established National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the U.S. War Department eventually agreed to establish an officer training program for qualified Black men, many of whom were college graduates, so long as the program remained segregated. Men who successfully completed the program would lead the all-Black troops who by now had been accepted as soldiers in the U.S. Army infantry. On October 15, 1917, following four months of intensive training, 624 African American men received commissions as officers in the United States Army. Included was Captain Joseph E. Trigg.

It has been my good fortune to observe the men, both at the Training Camp and on the streets of the city, and in both places their deportment has been the best. They have acquitted themselves like soldiers.

W. E. Harding, Governor of Iowa, August 2, 1917.

After two weeks of leave, the officers were assigned to different camps across the United States where they would train African American enlisted men in segregated units. Trigg was stationed at Camp Dix, New Jersey; Camp Meade, Maryland; and Camp Upton, New York. In June of 1918, Trigg began his overseas military service on French soil as part of the all-Black 92nd Infantry Combat Division of the American Expeditionary Force. According to the Dayton Forum, while in France “Captain Trigg took an active and credible part in the reduction of the St. Mihiel salient (bulge), one of the decisive battles in the war.” The American forces were under the command of General John “Black Jack” Pershing.

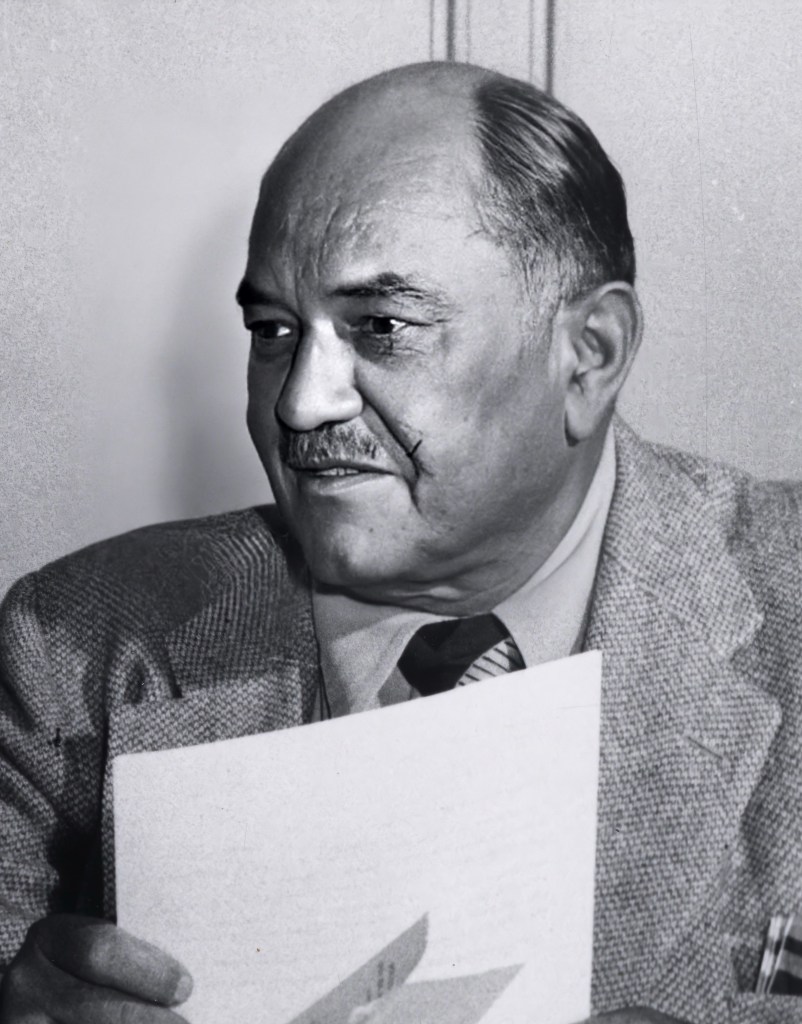

On April 25, 1919, Captain Trigg was honorably discharged from military service. In October of 1920, he matriculated at the Howard University School of Medicine in Washington, DC, where he would embark on a journey that would define the rest of his life. On June 13, 1924, Trigg graduated from Howard with an M.D. degree. The principal speaker at the commencement ceremony was President Calvin Coolidge. Upon graduation, Dr. Trigg interned at Washington’s Freedman’s Hospital, founded in 1862. It served the medical needs of the formerly enslaved. In addition to a degree, Trigg left medical school with a wife and a moustache, both of which would remain with him for the rest of his life. His medical school yearbook graduation quote was “Never quit,” a philosophy that would dictate his life’s work.

Although Trigg would never again pull an oar or throw a block following his days at Syracuse, he did remain involved in sports. While in Medical School, he was an assistant coach for Howard’s varsity football team.

After graduation, in addition to having a medical practice, Dr. Trigg served as a ringside physician for the boxing commission in Washington and later a ringside judge. In fact, in 1941 he was one of three ringside judges to decide the outcome of a closely contested championship heavyweight fight, the first in Washington, between then World Heavyweight Champion Joe Louis and challenger Buddy Baer at Washington’s Griffith Stadium. The fight ended in a controversial win for Louis. In 1950, Trigg, who had been judging boxing matches since 1934, was appointed to be a member of the District of Columbia Boxing Commission, the first African American to achieve such an honor. In an effort to make boxing safer, Dr. Trigg became an early advocate of the use of protective headgear for boxers following the death of Sonny Boy West, an up-and-coming Washington boxer whose head had violently hit the canvas during a match, resulting in his death the following day despite having had emergency brain surgery. At the time, the use protective headgear for boxers was contrary to conventional practice. However, Dr. Trigg pointed out that the first football helmets were initially criticized as “sissy,” but the public would eventually come to recognize the benefits of protective head gear in the sport. “In football, it was simply a case of educating the public,” Trigg noted in 1950, “and we hope the same will be true of the lightweight head harness (protective head gear) in boxing.”

As a physician, Dr. Trigg was described as “generous, courageous, and happy in the service of his fellow man” as evidenced by the fact that he belonged to numerous Washington-area charitable organizations. Despite a heavy and exacting general practice, he never ceased to maintain his primary interest in obstetrics. It was estimated that he delivered at least 1,200 infants, some of them two generations of the same family. He was praised as the biblical “mighty man of valor” (Judges 6:12) and was said to have had compassion and sympathy for Washington’s poor and disadvantaged.

In later life Trigg suffered from ailments reportedly related to his exposure to poison gas on the battlefields of France during World War I. On March 26, 1955, after a brief illness, Joseph Edward Trigg died at age 60. He was survived by Bernice, his wife of thirty-four years. Trigg’s life can best be summed up by the sentiments of a moving tribute published a year after his death:

He was big and strong. He had a great heart and he had known great victories on the athletic fields with which he was identified all his life, in the practice of medicine in which he worked for 30 years and in his inner spiritual life where he sought and found final fulfillment.

Journal of the National Medical Association, September 1956, 375.

Of Joseph E. Trigg, the one-time college oarsman, it can also be said that he was a trailblazer both on the water and off.

Thank you for the interesting story about Dr. Trigg. He was everything the sport of rowing hopes we at oars would become. Don Costello, Coos Bay, OR