18 July 2025

By Edward H. Jones

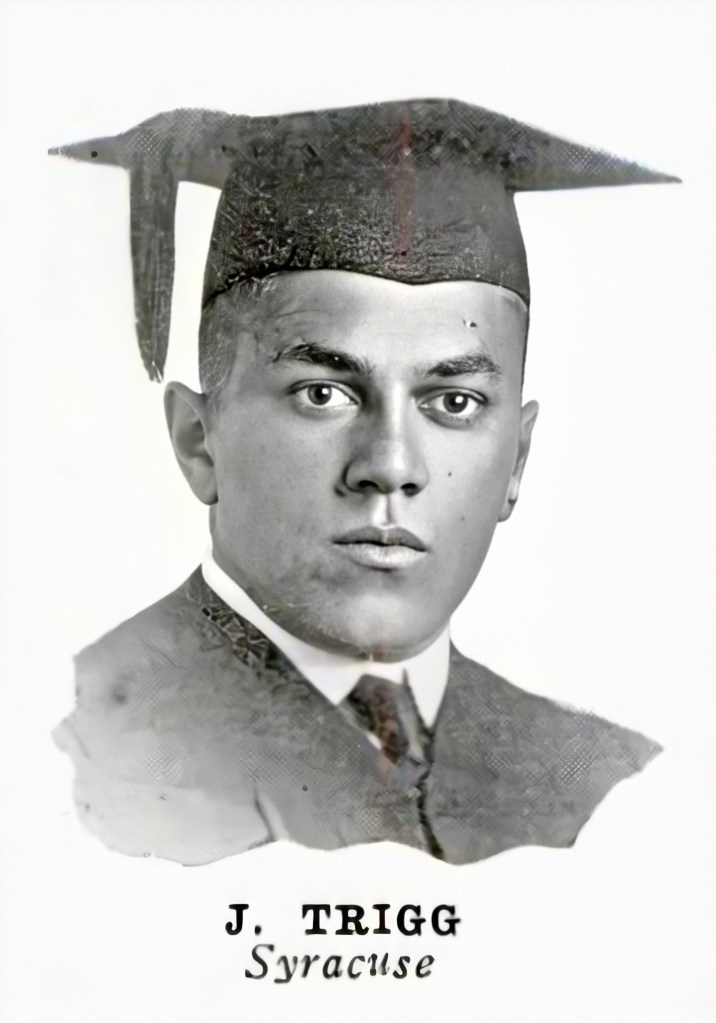

Joseph E. Trigg was a beloved Washington, DC, physician, who lived a trailblazing life of sport and service in the first half of the twentieth century.

Big Joe Trigg

Big Joe Trigg the athlete

played football and rowed crew.

Big Joe Trigg the soldier

fought for Red, White, and Blue.

Big Joe Trigg the boxing judge

presided over fights.

And Big Joe Trigg the doctor

stood up for patient rights.

By Edward H. Jones, © 2025

An Oarsman and a Lineman

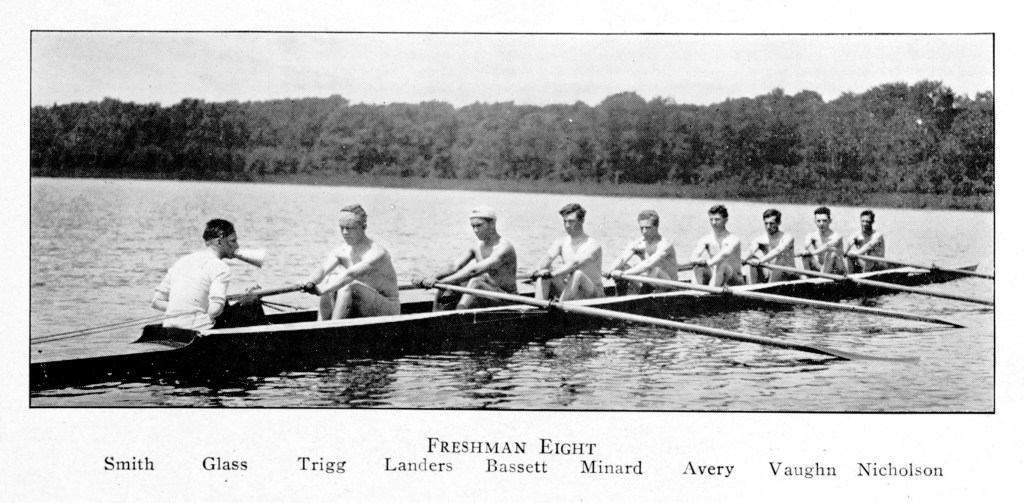

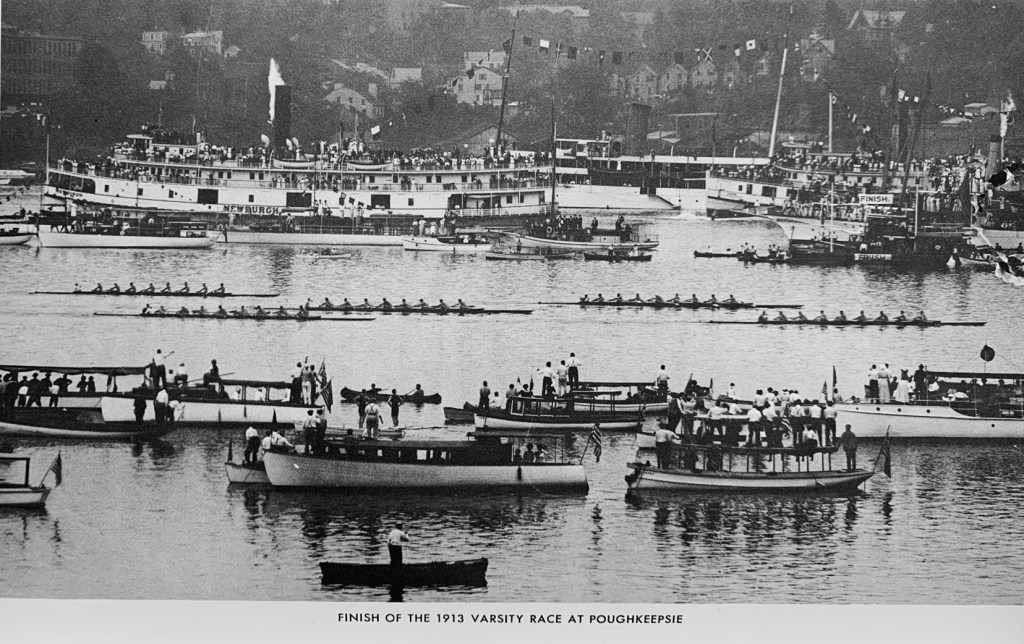

At 4:45 on a bright June afternoon in 1913, five eight-oared racing shells lined up for the start of a two-mile race down the Hudson River at Poughkeepsie, New York. Freshman crews from Columbia University, the University of Pennsylvania, Cornell University, Syracuse University, and the University of Wisconsin were about to compete for the Steward’s Cup at the eighteenth annual Poughkeepsie Regatta. The regatta was then considered the intercollegiate rowing championship of America and was held under the auspices of the Intercollegiate Rowing Association.

An estimated 60,000 spectators had gathered on this June 21st to witness the day’s activities from along the shoreline, aboard pleasure craft on the river, and aboard the forty-car observation train that would follow the rowers along the racecourse as a moving grandstand. It was reported that the observation train was so crowded that late-arriving passengers “hung like flies” on the ends and sides of the railcars.

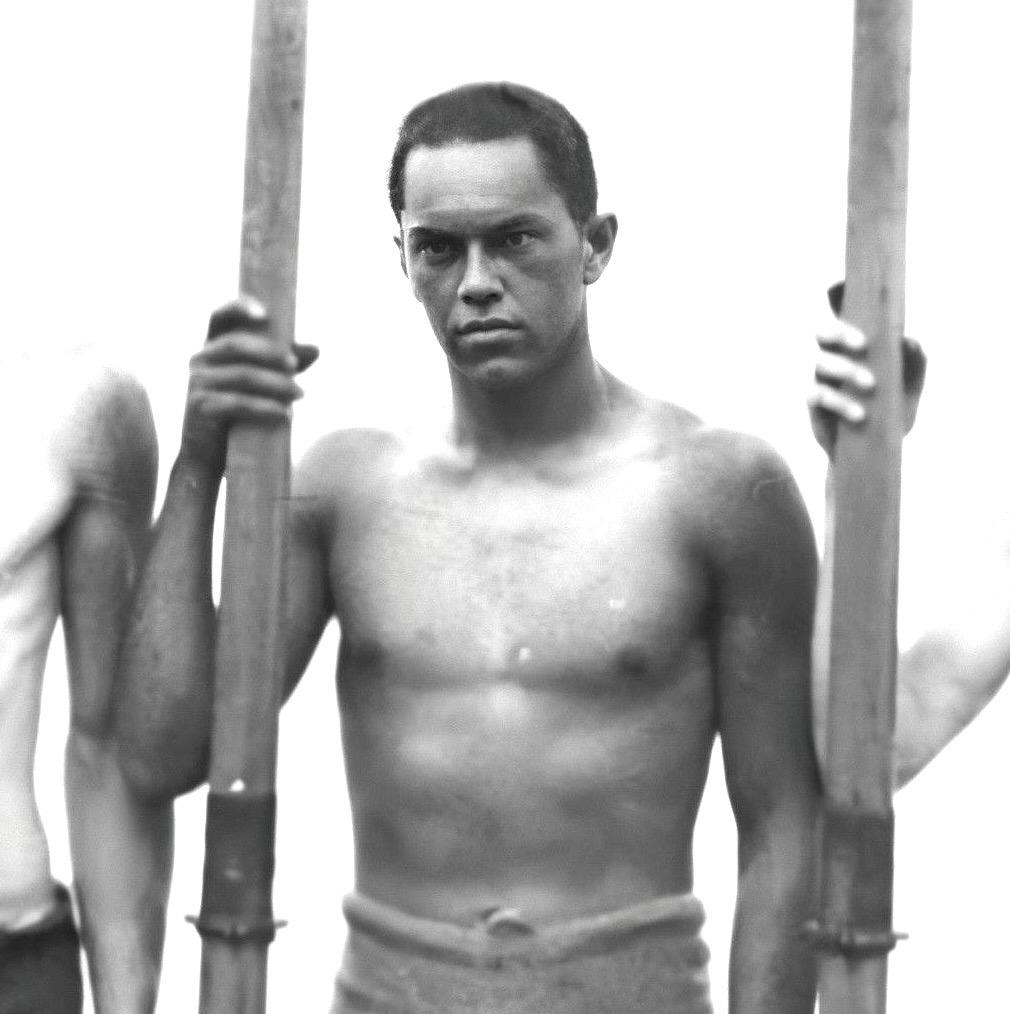

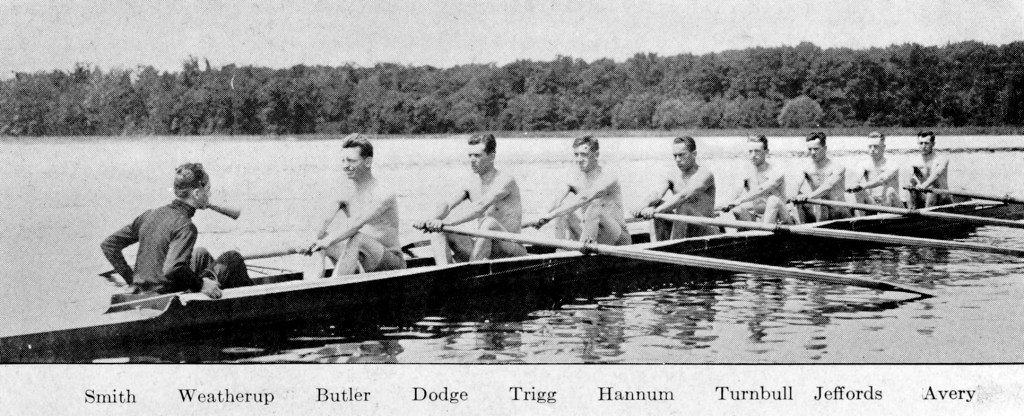

Pulling in the number 7 seat for the Syracuse freshman boat was nineteen-year-old Joseph Edward Trigg, the first African American to earn a position on a major American college crew. As such, he was also the first African American to row at the Poughkeepsie Regatta. At a time when African Americans on collegiate sports teams were few and far between – even for sports growing in popularity such as baseball, basketball, and American football – Trigg’s selection as a member of the Syracuse crew was even more of a rarity, especially given the fact that he had never rowed before his arrival at Syracuse.

Trigg’s accomplishment did not go unnoticed by both the mainstream and minority presses:

Perhaps Jas. (Jos.) E. Trigg is the only colored athlete in the big college crews and nothing but his proficiency won him the position he [has] with Syracuse. He is regarded the best all-around colored athlete in America and his career will be watched with interest. Knoxville Sentinel, June 28, 1913, 3.

Mr. Trigg has the distinction of being in recent years the only colored member of the big college crew of historic Syracuse University, winning his laurels by sheer merit and in the keenest competition that American youth can put up. Philadelphia Tribune, July 18, 1914, 1.

The Syracuse crews had arrived at Poughkeepsie nine days before regatta day to train and become accustomed to the racecourse. They stayed at Whittley House in the nearby village of Highland.

To ensure that his crews would not be distracted by newspaper reports, Syracuse head coach James A. Ten Eyck forbade his oarsman to read any newspapers during their preliminary training at Poughkeepsie:

Newspapers are a great thing, but sometimes the reporters become a little too loud in their praise of a certain individual. As a result that certain individual finds he is too good to row even a fair sort of race. Buffalo Sunday Morning News, February 2, 1913, 36.

Further, their regatta preparation included more than just rowing and racing:

The Syracuse crews did not go out at all this morning. Coach Ten Eyck thought it best to give his men a rest. The members of the Syracuse squad had a lot of fun on the float (dock) this morning ducking (dunking) the coxswains and substitutes. This ‘duck-fest’ is now an annual occurrence, and takes place a few days before the races. Evening Enterprise (Poughkeepsie, NY), June 18, 1913, 3.

As the number 7 seat in the Syracuse freshman eight boat, Joseph Trigg most likely enjoyed the benefit of being a “ducker” and not a “duckee.”

Conspicuously absent from the Poughkeepsie Regatta were crews from Harvard and Yale Universities who, a day before the Poughkeepsie races and a hundred miles to the southeast, had competed in their own annual boat race (The Race) at New London, Connecticut, on the Thames River, with the Harvard varsity eight emerging victorious. However, the absence of Harvard and Yale did not dim the public’s anticipation of race day. Poughkeepsie merchants were quick to capitalize on the opportunity afforded by the expected crowds by offering race-week merchandise specials. Although there were large crowds on race day, there was reportedly very little betting. Cornell, however, seemed to be the favorite in the varsity eights race, while Columbia, Syracuse, and Pennsylvania had their supporters for the freshman eights and varsity four-oared events.

On race day, the freshman eight-oared contest inauspiciously began with a false start due to the “jumping of a slide” in the Pennsylvania boat. After a restart, the Penn boat took the lead. At the half-mile mark, Cornell had taken over the lead with Syracuse second and Wisconsin third. At the mile mark, the order had remained the same, with Syracuse rowing at thirty-six strokes per minute to the thirty-two strokes rowed by Cornell and Wisconsin. At the mile-and-a-half mark, all three were rowing at thirty-six strokes per minute fighting hard for winner’s honors. Unfortunately, Joseph Trigg and his Syracuse freshman crew would fall behind. “The Wisconsin youngsters outgamed the (Syracuse) Orange eight, but could not overcome Cornell,” observed the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. As the crews passed the finish line, Cornell had a three-quarter boat length lead over Wisconsin, who in turn was about one-and-a-half boat lengths ahead of Syracuse.

Although Trigg and his fellow Syracuse freshmen had “started bravely” and was an early factor in the race, they unfortunately could not keep up the pace and fell victim to Wisconsin and to Cornell, the eventual freshman eights winner. As for the Syracuse varsity four, it disappointingly failed to finish the race following a near collision with a rowboat. However, the regatta would not be a total disappointment for the Orangemen from the “Salt City,” as the Syracuse varsity boatmen would defeat five other coxed eights later that day to win their four-mile race and secure the Varsity Challenge Cup for their school with a winning time of 19 minutes, 28 and 3/5 seconds.

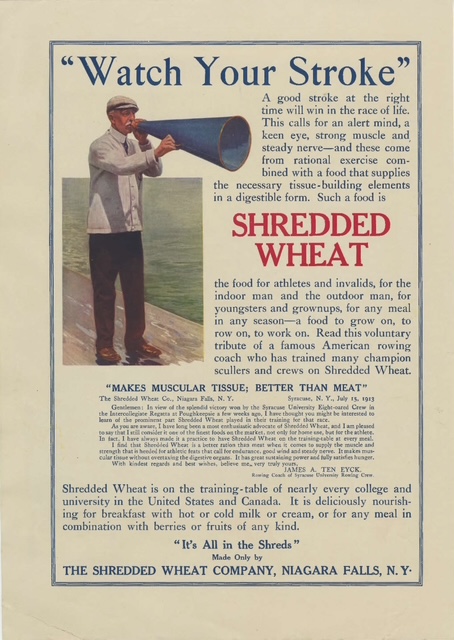

The coach of the Syracuse crews was the former professional oarsman James A. Ten Eyck, himself the son of a professional oarsman. He would become known as “The Grand Old Man of Rowing,” and years after his death would be inducted into the National Rowing Hall of Fame. His Syracuse varsity eights had previously won at Poughkeepsie, first in 1904 and again in 1908 when his son, James E. Ten Eyck, pulled in the stroke seat. Other notable former professional oarsmen coaching crews at Poughkeepsie that June afternoon in 1913 were Cornell University coach Charles E. Courtney who had waged notable sculling battles against Canadian champion Edward “Ned” Hanlan; University of Pennsylvania coach Ellis F. Ward of the famed Ward brothers rowing family; University of Wisconsin coach Harry “Dad” Vail for whom the annual Dad Vail Intercollegiate Regatta was named; and Columbia University coach James Rice who was once a sculling protégé of Ned Hanlan, a.k.a. “The Boy in Blue” for Hanlan’s trademark blue racing attire.

The victory by Coach Ten Eyck’s varsity eight at Poughkeepsie this day catapulted him to celebrity status. In 1914, a year following the win, Ten Eyck appeared in an ad in Suburban Life: The Countryside Magazine endorsing Shredded Wheat breakfast cereal. This was twenty years before General Mills would launch its iconic “The Breakfast of Champions” ad campaign for Wheaties™ breakfast cereal featuring prominent athlete endorsers beginning in 1934 with baseball great Lou Gehrig. Some of the articles appearing in that 1914 Suburban Life issue included “Piping Rock, a Great Country Club,” “Transplanting the Decorative Fern,” “A Notable Summer Home,” and “My Friends the Woodpeckers.” Placing an ad featuring the Syracuse head crew coach in a magazine such as Suburban Life no doubt did little to dispel any notion that rowing was an elitist sport.

Joseph Trigg would go on to earn a seat (number 5) in the Syracuse junior varsity boat his sophomore year in the spring of 1914 and a seat (number 7) in the varsity boat his junior year in the spring of 1915. Early in 1914, the Boston Evening Transcript noted that with Trigg and four other oarsmen, coach Ten Eyck had “some good men” to help fill the junior varsity eight. Although Trigg would earn the block letter “S” award as a member of the Syracuse varsity crew in his junior year, he unfortunately would never experience the satisfaction of having been part of an intercollegiate rowing championship crew. Third place was the best finish Trigg’s boats were able to achieve at Poughkeepsie during his three seasons as an oarsman at Syracuse.

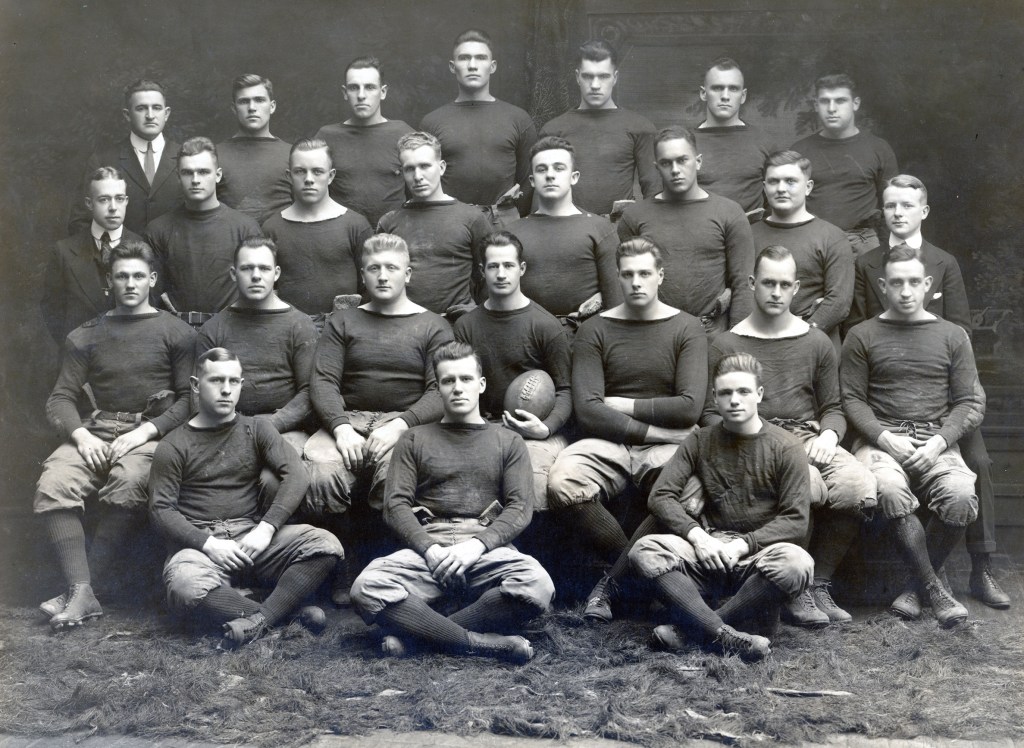

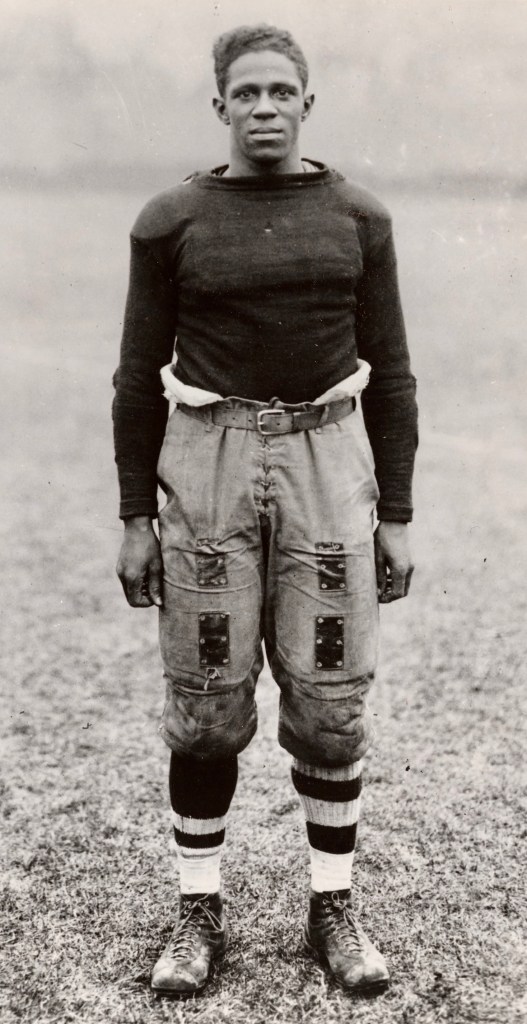

At 6 feet, 1 inch and 180 pounds – as Trigg was listed in the Regatta Official Program – he was the tallest and heaviest crew member in his freshman boat at Poughkeepsie that day in 1913. His size served him well. Not only was he an accomplished oarsman on the water, but he was a formidable lineman on the gridiron. Trigg had entered Syracuse in the fall of 1912 and earned a position on the freshman football team as an offensive guard. He was the first African American to play on a Syracuse football team.

Born in Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1894, Joseph Edward Trigg was the eldest of four children. In 1898, his family relocated to Washington, DC, where his father had been appointed to a clerkship in the U.S. Post Office. Young Joe Trigg attended the city’s historic all-Black M Street High School, later renamed Dunbar High in honor of the noted African American poet Paul Lawrence Dunbar. In the first half of the twentieth century, the school was an academically elite public educational institution which attracted an exceptional faculty, despite being racially segregated by law. Trigg was a stellar student in the classroom and a standout lineman on the school’s football team. The school was such a football powerhouse that in 1909, with Trigg at right guard, the high school team defeated Storer College, a small, historically Black institution that had existed at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The coach of the M Street High football squad was teacher Haley G. Douglass, himself a graduate of M Street High, as well as Harvard College (class of 1905). He was the grandson of famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass, and while teaching at M Street High, he also served as mayor of Highland Beach, Maryland. At Harvard, Haley Douglass, like Trigg, was involved with crew and football, but only at the club level, unlike Trigg who rose to compete for his university at the varsity level. As the coach of the M Street High football team, Haley Douglass was praised for turning out “a championship bunch of players” while working all alone and he deserved “the entire credit for the (successful) results.” Decades after his coaching days, Douglass recalled during an interview that “Big Joe,” as Trigg was called in high school, had no trouble making the high school team “because he could follow instructions to the letter, and while always not flashy and colorful, was a consistent performer.” In 1911, the Washington Herald described Trigg as “an essential part of the mechanism” that wrought for the school “a really effective offensive machine.”

Upon graduation from M Street High, Trigg entered Syracuse University on a scholarship where he continued to display his gridiron prowess. During his first season in 1912, Syracuse had scheduled a freshman football game against a nearby high school, a practice not unheard of back then. When the opponent’s running back fumbled on the Syracuse twenty-five-yard line, Trigg “grabbed the pigskin and raced to the [opponent’s] four-yard line,” setting the Syracuse quarterback up for a four-yard touchdown run.

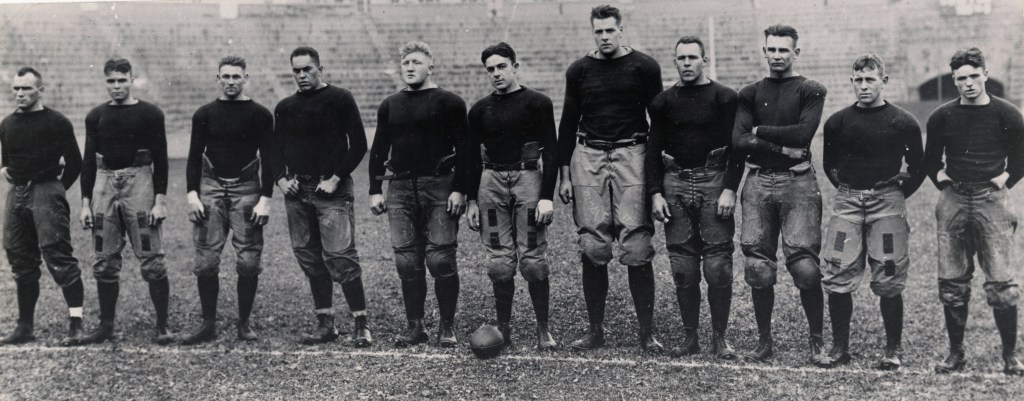

During the 1913 season, the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle described Trigg as a strong and dependable guard who should in the future prove to be a good running mate to the heavy Syracuse tackles. At the end of the 1913 football season in his sophomore year, Trigg was one of twenty-two players awarded the block letter “S” as a newly elected member of the team’s varsity. In 1914, during Trigg’s junior season and following a lopsided 81- 0 win against Hamilton College, the Buffalo Post noted that at left guard he was one of three Syracuse players who “showed to the best of their ability and at all times put up a sterling game.” A few weeks later, following a Syracuse win against the University of Michigan, the Norwich (CT) Bulletin stated that Trigg “had little trouble in making holes for Syracuse backs to charge through.”

Some men hitherto unnoticed played well yesterday. Joe Trigg, last season’s crack guard, appeared in the reserve line for the first time since injuring his ankle at the beginning of the season. Trigg played a great defensive game. That he will soon earn a place as a regular is the opinion of all who watched his splendid work yesterday (during a grueling scrimmage). Buffalo Post, October 2, 1914, 6.

At the start of the 1914 football season, Coach Frank “Buck” O’Neill announced that for upcoming games, Syracuse would implement the novel concept of sewing numbers on the backs of the players’ jerseys so that the spectators “may follow the players intelligently.” The numbering of players “has been used with great success at many Western universities,” O’Neill told the Daily Orange school newspaper, “and is being tried this year in several Eastern institutions.” With the innovation of numbering, spectators will no longer have to try to pick out star players from “a struggling mass of humanity,” wrote the Buffalo Times. Joe Trigg at guard was assigned number 15.

Before returning to college in the fall of 1915, Trigg became somewhat of hometown celebrity when, as assistant director of Willow Tree Park in the city’s southwest section, he oversaw the first all-Black, city-wide playground swimming meet, described by the Washington Bee (perhaps with a bit of hyperbole) as “the greatest sporting event in the history of Washington.” A front-page story describing the event was accompanied by a photo of Trigg with the caption “Progressive and Active – Successful Student and Athlete.”

Later that October, during a game against Brown University, Trigg came in to replace the injured Syracuse left guard who had been kicked in the eye. Following Syracuse’s 6 – 0 win, the Detroit Free Press predicted that Trigg “may replace one of the regular linemen in the very near future.” In Trigg, the Free Press asserted, Syracuse had a substitute “that will fill any hole in the line that might be caused by injury fully as well as the regular himself.” Interestingly, toting the ball at halfback for Brown that afternoon was another trailblazer – Frederick Douglass “Fritz” Pollard – who would become the first African American running back chosen as a consensus All-American by recognized selection entities including Walter Camp, known as the “Father of American Football” for his contributions to the evolution of the early game. “Pollard was one of the most difficult men I ever tried to tackle,” Trigg recalled many years later; “He was the first to show all the hip motion and side-stepping tactics to evade a tackle.” Among Pollards firsts, on New Year’s Day in 1916 he became the first African American to participate in a Rose Bowl football game. However, this honor might have gone to Trigg.

According to the “Syracuse Football Chronology” posted on the Syracuse University Athletics webpage and included in the Syracuse Football 2024 Media Guide, invitation to what would become the annual Rose Bowl New Year’s Day football classic in Pasadena, California, was initially offered to Syracuse which at 9-1-2 had a better season record than Brown’s 5-3-1. But Syracuse purportedly would have to decline the invitation because the team had depleted its travel budget as a result a trip to the West Coast (the first by an Eastern school) to compete against Oregon State University. Therefore, the honor of being the first African American to play in the very second Rose Bowl football game went to Pollard. He would go on to become the first African American head coach in the fledgling National Football League when he served as both player and co-coach of the Akron (OH) Pros in 1921. Four years later, Pollard would become the sole head coach of the Hammond (IN) Pros. With Trigg and Pollard crossing paths on the gridiron that October afternoon in 1915, fans witnessed the conjunction of two (trail) blazing stars in the galaxy of college athletics.

Defensive play is Trigg’s specialty, although he shows plenty of aggressiveness on the offense. He charges low and hard and generally gets his opponent by his quickness before the latter is aware of it. Washington Bee, November 13, 1915, 2.

Trigg would play football during the 1916 season as a fifth-year senior, attributing the extra year to the fact that he was injured one year and didn’t play the full season. In an early review of the 1916 season, the Asbury Park (NJ) Evening Press reported that “the playing of Captain White and Trigg, the two star lineman, has been impressive this week, both showing much aggressiveness and skill in breaking up plays.” Syracuse would finish the season with a 5-4 record.

On June 13, 1917, Trigg graduated from Syracuse with a Bachelor of Science degree. Two months earlier, on April 6, 1917, the United States had declared war on Germany in part a result of German submarine attacks on U.S. shipping in the North Atlantic. Thus was America’s entry into World War I, and Trigg would soon answer the call of duty.

Part II will be published tomorrow.