16 June 2025

By Aaron I. Jackson

Dramatising the incredible true story of Tyneside’s Harry Clasper, nine-time world rowing champion and the greatest sportsman of his or any other era, Ed Waugh’s classic play Hadaway Harry enjoyed its tenth-year anniversary revival earlier this year. Witnessing Jamie Brown’s powerhouse solo performance of the play, Dr. A. I. Jackson, rower, the Northern One of Broken Oars Podcast, and an academic specialist in British identities, notes the significant questions Harry’s life and Waugh’s play raised about sporting and cultural representation in Britain remain unanswered as we head into the Regatta season in the rowing calendar. (Read Part I by clicking here.)

v. We Don’t Talk About Harry

When I was an academic, I saw things as an academic does. But life’s circumstances mean I have now put away such foolish things. Nevertheless, once you’ve trained yourself to think and consider and weigh and evaluate and ask questions and query answers, it’s a hard habit to get out of. I started young:

‘Why is the sky blue?’

‘Rayleigh scattering, where shorter wavelengths of light, like blue, are scattered more by the molecules in Earth’s atmosphere than longer wavelengths, such as red.’

‘Yes, but why?’

Anyway, what rower doesn’t like thinking about or talking about rowing? Seeing Hadaway Harry again recently, diving deeper into Harry Clasper’s story as a result and the imminence of the annual Boat Race at the time made me think about how we celebrate and present rowing in Britain. William Blake once suggested that we can see the universe in a grain of sand. The man’s Tyger, Tyger burning bright in the forests of the night looked like bagpuss, but he was right: in the microcosm is the macrocosm. How we celebrate and present rowing in Britain is how we celebrate and present everything else in Britain.

Let’s suggest something.

Let’s suggest this:

There is no modern rowing without Harry Clasper. There’s no fine shell and none of the innovations we now take for granted as rowers. He popularised the sport. As many people regularly turned out to watch Harry race in Newcastle and London some 175 years ago than Henley Royal will get in a full good week this summer, even in its expanded format. Draw a line through and we could say that without Harry there’s no British five charging out of the mist of Lake Casitas in ‘84, starting the unprecedented run of success British Rowing has been on ever since as an Olympic sport. There’s no Redgrave, no Pinsent, no Grainger, no Hodge, no Glover, no Olympic heroes thrilling and inspiring and no resurgence of interest in the sport at all levels. To put it bluntly, without Harry (and others like him) there’s no rowing as we now understand it.

And yet there is no statue* to Harry or his epic battles with Coombes on the Tideway, or stockily opposite Redgrave’s in Leander’s entrance. There isn’t even one of him on the Quayside at Newcastle. All Harry Clasper has is a Blue Plaque, some metal horses only rowers ever see on the banks of the Tyne at Blaydon, just along from the railway station, and Ed Waugh’s play reminding us that he once was.

Why?

Maybe it’s our fault (and by our, I mean the North-east of England) Harry hasn’t been rehabilitated and reintroduced to the story we tell about British Rowing.

What do I mean by that?

Well, let’s break it down.

Even if we weren’t born there and have never visited, we all know what Tyneside is, right? The men are all canny lads, the women are all canny lasses. All the lads are called Jackie and so are a lot of the lasses. Football is a religion. Black and White. Magpies. St. James’s Park is the cathedral on the hill. Stotties. Whippets. Geordie had a pigeon, a pigeon. The Tyne, the Tyne, the mucky Tyne, the Queen of all the rivers. Howay man. Whey haddaway and shite, bonny lad. Where’s wor lass?

It’s an absolute nonsense of a regional stereotype, reducing an area the size of the interior of the M25 and just as long a history of continuous settlement to a Viz caricature. The equivalent would be to describe London by pointing to a picture of The Krays and making people watch Eastenders. No-one from the region calls St. James’s Park the cathedral on the hill, only Southern journos up to commentate. We have two cathedrals and produced the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Venerable Bede when the Thames Valley was still getting to grips with woad and rabbit skins so we’ve also a reasonable understanding of what an actual religion is, thanks, and if we’re going to the football we say ‘we’re going over the town to watch the match’ not ‘I’m off to worship now, pet.’ Nor do we all sound like Brenda Blethyn in Vera. We don’t charge around the more picturesque spots in a vintage Landrover wearing clothes a baglady would reject saying ‘And so you lost y’tempah and y’kilt them, didn’t y’, pet? Y’ kilt them.’ Yes, that’s right. Officer. We got really pissed off with them and put them in Scots national dress – which given we’re on the subject of whitewashing in history was worn by landowners, aristocrats, British Army Generals and Anglo-Scots when the actual Highlanders who came up with the plaid had been reduced to a despised underclass. (Seeing a parallel here? No? Shall I make it explicit?) And we pronounce Prudhoe as Prudda, so I’ve no idea where Ruth from The Archers is actually from but it sure as eggs are eggs isn’t the village just along from Crawcrook in the Tyne Valley.

Quips aside, I’m from the area. I was born up the valley from Newcastle in Hexham. I grew up alongside the river Derwent, just up from where Harry had his boatyard and where he trained on the Tyne. I never heard about Harry Clasper, growing up. Or rowing. Not a word. I had to move to Manchester and be inspired by Gold Fever to find the sport and then fall in love with it. Even then, it took going to see Hadaway Harry for the first time because I was a rower and it was about rowing for my eyes to be opened to an entire history of my region and its wider role in my sport I was otherwise completely unaware of.

By chance, in other words.

Maybe that’s on us.

Growing up, I didn’t know I was from the North or what that means in terms of how everyone else in the country sees you. As children, you think what’s around you is what’s around everyone. I knew Newcastle was about ships and coal and steel and iron and heavy industries and engineering in the same way that I knew there was a moon and stars in the sky at night and a green around the corner I could kick a ball on. No-one made a song or a dance about it. I thought everywhere else must be the same. When I moved to Manchester and then Sheffield, however, I found out everyone else did and it wasn’t. It seemed I’d barely stepped off the train at Piccadilly before a Mancunian in a United replica shirt with a face like pickled walnut under a bucket hat was telling me I was in the workshop of the Industrial Revolution; the home of steam; the place that had the world’s first railway; a place that had done the work of a capital while the capital was busy doing nothing other than write Knees Up, Mother Brown; a place who built an entire canal system just to piss off Liverpool; a place that had provided the world’s most important bands in Joy Division, New Order, The Smiths, Happy Mondays, Oasis and The Beatles, who, apparently, changed trains there once on their way out of Liverpool and down to London. In Sheffield, you’re literally confronted by a giant poem on the side of one of Hallam’s buildings as you leave the train station telling you you’re in the place that was – yes, you’ve guessed it – the workshop of the Industrial Revolution, producing steel, coal, cutlery and dour blocking opening batsmen who were about as much fun to watch as paint drying.

It’s all tribal knockabout, of course, especially when you work out pretty much everywhere in Britain from the Clyde to the Thames can claim to have been the birthplace / heart / workshop of the Industrial Revolution / Empire / World. We were a small island in the mid-Atlantic with a big Empire. The whole island was a workshop. Even London had factories. What’s odd, however, is everywhere but Newcastle tends to have a riff like this when Newcastle doesn’t, but is actually the place who has the most claim to it. Manchester didn’t invent the railways. Or steam. On a nice night, if the tide is up, you can paddle up towards Wylam to the cottage where George Stephenson put The Rocket together and tested it. Trains and carriages made on Tyneside went all over the world. What’s left of Britain’s rail networks still runs on rails designed by Stephenson, whose proportions were taken from the grooves worn in the gatestones of Vindolanda by the steel-wheeled carts of the Roman legions. Good enough for Caesar, good enough for you. Yes, Sheffield produced coal and steel and cutlery. I lived there for eight years. They never shut up about it. What I didn’t know growing up here was Newcastle also did and in more volume than anything South Yorkshire ever achieved. Tyneside also produced more gritstones than Stanage and Derbyshire too. A college at Cambridge was said at one time to have produced more Nobel Prizes than the rest of Europe. Well, at one point Tyneside held more engineering and technological patents than everywhere else in the country. First house with electricity? Tyneside. Shipbuilding? Tyneside was building ships for the King in the thirteenth century. Turbines? Parsons. Revolutionising the pottery making process? Tyneside. Armaments? Armstrongs, along Scotswood Road – still the 10k turning point for anyone rowing from Newburn towards town. Refining the glass-making process? Tyneside. Pionering attractive attacking football? Since World War Two, Tyneside has produced more professional footballers per capita than anywhere else in the country, among them the most creative players of their generation. First Women’s Football teams? Tyneside. Going out in winter without your coat on? Tyneside. And so on and so forth.

So perhaps Clasper’s achievements and his startling lack of recognition is because we don’t shout about ourselves. My Grandfather was part of the team who designed, built and installed the hydro-electric turbines at the Aswan Dam in Egypt. Never mentioned it. Not once. I found out about it after he died. Where Greater Manchester Council hires people to tell you how amazing Manchester is and Sheffield writes its past on the side of buildings, we just look at you and say ‘are you going over the town on Saturday to watch the match?’ Maybe if we did shout about it more, or maybe if we’d had a Harry Clasper impersonator greeting people as they came into Newcastle Central station, he’d be more widely known about and I wouldn’t have had to see Gold Fever while living in Manchester to discover rowing when the Tyne was literally rolling past my window growing up.

Or maybe it’s this:

Maybe it’s because Harry Clasper was working-class – and the working-class are spear-carriers in the history of Britain, never the leads. We’re good for inventing things and doing things and fetching and carrying and being cannon-fodder if there’s a war, but that’s about it. Our job in rowing was to invent the sport, popularise and refine it and then watch as someone else took charge of it and told us we weren’t welcome.

I’m not being snippy.

This is a fact.

It happened.

And it happened like this:

vi. Shamateurism

The history of amateurism in British sport has been well-covered and explored elsewhere, both in the academy and also pop-culture, but it boils down to this: as hard-won employment concessions invented the idea of leisure time for the masses in the post-Industrial Revolution period, and participation in sports rose, the middle and upper-classes invented the idea they were the custodians of the spirit of the game. They played for love, not money.

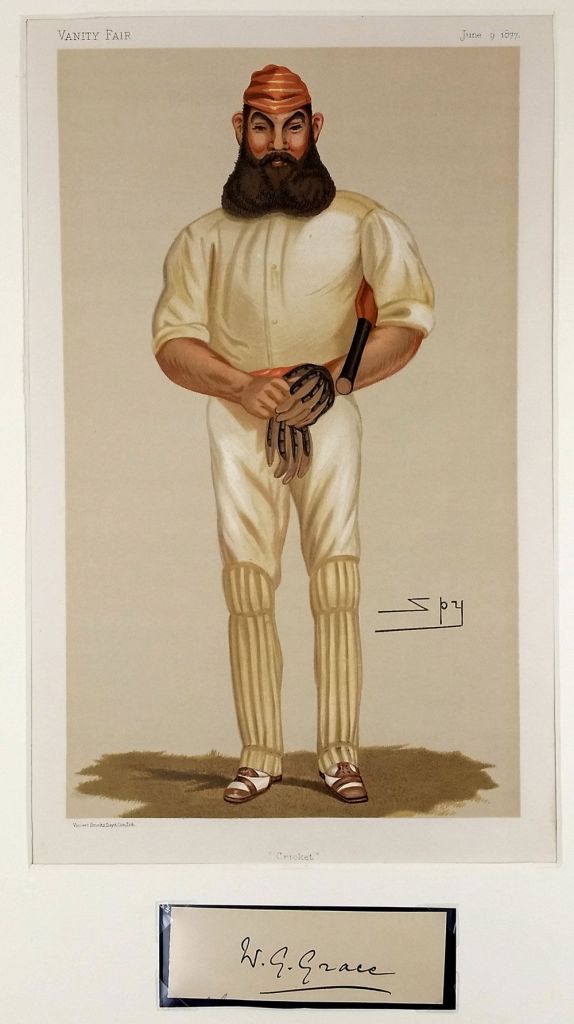

Then and now it was absolute nonsense, of course. W.G. Grace and his brothers made more out of cricket than any professional ever did and did so with an utterly shameless hypocrisy even those who signed off on their ‘expenses’ occasionally balked at. The invention of amateurism was never about keeping the Corinthian spirit alive, but allowing the middle-classes to continue to participate – because from the turf to the cricket square to the rugby pitch to the water if representative selection and participation and competition had been organised on merit or ability, they’d have been in the stands watching as the plebs swept the board. It was, then, a form of sporting apartheid.

It was so brilliantly organised and sold, however, using existing ideas about class and station, it was not only accepted but seen as perfectly natural. The gentleman amateur turning out for his county when other commitments allowed (and taking the place of the professional who needed the match fee to feed his family) could afford to play the risky late cut to a spinner on a turning pitch. After all, whether he holed out or sent it to the boundary he was displaying the dash and flash that was the ‘true’ spirit of the game, rather than those dour pros who got their runs in ‘vuns and twos.’ If the gentleman amateur threw away his wicket, he could laugh ruefully about his ‘bally bad luck’ on the way to the Pavillion, knowing he didn’t have to worry about being dropped or ending up in the workhouse. These ideas – that there was a game beyond the game far nobler and truer than those who played for a living would never know – entered not only Britain’s language but also our representative culture. We still, lingeringly, have these notions. The fair go comes from having a fair unhandicapped fight in the prize ring, as does the idea of coming up to scratch. We are British, so we play ‘with a straight bat’ – correctly, in other words, rather than across the line or with the wristy innovations of a Ranjitsinhji. Keeping a stiff upper lip comes from the idea it was somehow unmanly to wear cricket pads or indicate you’d been hurt when a shooter kept low and shattered your shinbone. Team sports as character-building and training for life, winning and losing well, walking without being told, accepting the umpire’s decision, treating triumph and tragedy the same … These ideas are not just historical echoes. Despite being much-worn and threadbare now, largely because they’ve been used without care or real understanding by scoundrels, they are as much the shibboleths and touchstones of what it means to be British even now at the end of the first quarter of the twenty-first century. They were mobilised and sent into battle alongside the idea that England is a green field and a country lane and the white cliffs of Dover as recently as the Brexit vote.

The examples above are largely drawn from cricket – which became and remains a deeply schizophrenic sport in being forced to overlay this idealised narrative onto its rackety, racey origins and social realities. But the biggest impact these ideas had was in rowing. Rowing was seen at the time as the ultimate manifestation of the ‘Muscular Christian’ ideal that became a central plank of late-British imperialism. More than any other sport, rowing required that the individual sacrificed themself for the good of the collective. The sculler in their single was engaged in the practice of an art (plus ça change …) but the eight was the epitome of what society wanted from its gentlemen: self-sacrifice, teamwork, everyone pulling together in the pursuit of a single goal. Remember the whole Blakean universe / grain of sand / bagpuss thing? As in the boat, as in life, as in the Empire. Clubs already existed, but more were formed. Leander was one of them. These weren’t for watermen. These were for gentlemen. Watermen like Harry wouldn’t have been welcome. They didn’t represent what their social betters wanted the sport to be.

Harry didn’t row for ideals.

Harry rowed for money.

Harry wasn’t a gentleman.

Harry was working-class, with a trade rather than a profession or independent wealth.

For God’s sake, the man didn’t even get to vote until 1868, when he was 56, and then only because he finally met the property criteria.

What next? Women? Haugh, haugh.

If we’re being honest we’d say Harry, the plebs and the ‘professionals’ didn’t get to row against the gentlemen amateurs because the gentlemen amateurs knew they’d have been horizoned if they had. And if that had happened, who knows what might have ensued? Emboldened by seeing the toffs humbled in a paddle, Britain might have succumbed like the Continentals to revolution, fire, brimstone, rains of cats and dogs, women training at Leander and the end of all moderation and propriety. (That last happened in 1997, by the way. Not because of a long-overdue recognition that girl rowers were just as good as boy rowers, but because Leander wouldn’t have got its lottery funding otherwise. Still, nice to know it happened for the right reasons, eh?).

But we aren’t honest, so we invent reasons why it should be us and them. We talk about the spirit of the game and the Corinthian ideal. We start throwing words around special, unique, exceptional … and then decide who gets to have that label attached to them and who doesn’t. That Harry and others like him aren’t talked about isn’t some fault of Geordie character. Listen to wor accents, man. We’re a region who loves to talk. We literally invented the word gobshite for members of our tribe who talked even more than the other very talkative members of our tribe. Ee. They’re a right gobshite, them. It’s because they weren’t welcome in what the social elites wanted rowing to be:

Theirs, not his.

Ours, not yours.

Exclusive, not inclusive.

This has not changed.

This is the same language that this year’s Boat Race and its contestants is framed as.

Special. Unique. Corinthian.

Last year, as the message exchanges indicate, special degree violin commentator interlocutor issued the following Parthian shot about the Boat Race:

So what? It’s our thing anyway. If you don’t like it, you don’t have to watch it.

Leaving aside the fact that I’m a rower, I like watching rowing, and I love the Boat Race a polite response might have been Yes. You’re right. I don’t have to watch it. (Tugs forelock, sorry measter, I forgots myself.)

A snarkier but more accurate response might have been something like this: Really? If it’s your thing, your special thing just for you, why don’t you stop broadcasting it on the world’s leading independent and impartial public service broadcaster to a global audience, turn the cameras off and go and have your bunfight on a quiet river somewhere with no-one watching? After all, you’re Corinthians, right? You do it for the love and spirit of the thing rather than external recognition or the demands of crass commercial imperatives …

I didn’t say this because I had already walked away by then. Children and bigots, remember?

Later, it stuck me who else uses the phrase ‘our thing.’

La Cosa Nostra.

And they too walked off with things belonging to other people and then reacted violently when others pointed it out.

vii. So What?

Now, let’s pretend your correspondent didn’t once listen to Dr. Hynes on Broken Oars Podcast talking about lactic millimoles and then spend the rest of the day imagining small subterranean mammals doing 2k tests. Let’s also pretend he didn’t also think moles might turn out to be really good at rowing because they can tolerate higher levels of carbon dioxide than other mammals. Their blood has a special form of hemoglobin that has a higher affinity to oxygen than other forms, and they’ve incredibly efficient at reusing exhaled air. If only they weren’t so damned short. Still, perhaps at bow …

Yes. Let’s pretend that didn’t happen, and unravel a few of the points made above. We’ll do it in the form of a Socratic dialogue, because I’ve just admitted to pondering whether a polydactylic forepaw might be an advantage to a rower (and also because I find the word ‘Socratic’ onomatopoeically pleasing to say and write and it’s a good form to explore ideas in). We’ll imagine that special degree violin boy is raising the windmills for me to tilt at.

Here goes:

So what? Conquered tribes since the time of Caesar have been encouraged to revisit old campaigns and air old grievances. It keeps them occupied while others get on with ruling the world. Going back over this isn’t going to change anything. Besides, we’re a meritocracy now, aren’t we? I’ve heard you say on Broken Oars Podcast that you consider Henley Royal Regatta one of the most important elite sporting events in the world precisely because you only get to compete there if you’re good enough.

You’re right. I did. My exact words were that nothing else like Henley exists in sport. No-one picks up a tennis racquet for the first time and walks out on Centre Court nine months later. No-one laces up a pair of boots for the first time and contests the FA Cup Final nine months later. But you can do a learn-to-row course, start your season in September and with hard work and a bit of luck line up on the Henley start line the following July.

That’s not just brilliant.

That’s utterly, utterly priceless.

Well, there you go then. Anyone can do it. Hoist by your own pet toad.

Petard, actually. It’s a small sixteenth-century bell-shaped breach bomb. To be hoist by it means to be blown up by your own bomb. Toads aren’t hoisting anything. Moles, now, with their polydactylic forepaws …

And no, anyone can’t.

Here’s a fact for you.

The majority of those representing Britain at international level pre-lottery funding, including Olympians, came from state-school sector backgrounds with the rest coming from private-school sector backgrounds.

Post-lottery funding, the majority of those representing Britain at international level come from private school sector backgrounds, with a small minority coming from state school backgrounds.

The percentages are reported differently depending on which study you read, but what it means is this: sporting representation previously mirrored society. Now it doesn’t.

Here’s another fact:

Pre-lottery funding, the majority of children up to post-compulsory education age reported regularly being involved in a sport or activity.

Post-lottery funding, more children than not up to the same threshold report not regularly being involved in a sport or activity.

Here’s another fact for you:

Participation in sports in the UK is down in all demographics, but particularly among children and teens, with young girls being hit the hardest.

Why is that?

Well, there are a complex of reasons, but they’re interrelated.

One reason might be that private and public schools weren’t encouraged to sell off their sports fields and playing facilities to make ends meet like the state sector was in the 1990s. It was a Conservative Government who did this, and they did it in the teeth of a host of experts telling them it was a bad move and would lead to a) lack of childhood participation in sports, and therefore lack of lifelong engagement in sports; and b) concomitant issues in child health, including increases in obesity, morbidity and diet and exercise related diseases like diabetes.

Still, we don’t need to listen to experts, do we – even though they turned out to be right, and the Prime Minister who forced it through at the time (John Major) later admitted it was an absolute horlicks of a policy for the health and wellbeing of a nation now per capita fatter and more inactive than America.

And it might also be said that as well as having sports fields and playing facilities to use, private and public schools also have staff who can run teams, organise squads and activities and teach and train extracurricular activities for the benefit of their students.

Coming from a family of very successful, highly-qualified state school sector teachers, in the first part of their careers every single one of them from the seventies to the nineties routinely ran extracurricular activities for students. They set up football and rugby and cricket and swimming and athletics and drama and music and painting and book clubs. They organised training sessions and competitions with other schools. They took students to London to experience the National Theatre and Edinburgh to the Festival. They drove mini-buses. They organised cross-countries and inter-schools events. They gave up nights and weekends to ferry children who weren’t theirs around so they could experience all of these things.

Unpaid.

Why?

I don’t know. Perhaps it was a reflection of a more inclusive societal attitude. Perhaps it was because they wanted to share their passions with others and expose them to positive opportunities. Perhaps it was a legacy of realising how much they’d benefited from the post-war settlement and the opportunities it had offered them: You might be from a council house, but so am I, and I still got to University and got to do these things. You can too.

Perhaps it was because they were just decent people.

In the second half of their careers, swamped by rising class sizes and a tsunami of administration and red tape, all of them stopped doing those extracurriculars.

Because they didn’t have time.

So what? Even in state schools, you can still pay for extracurriculars. You can send your child into a Breakfast club or Afterschool club if you have long working hours and you can get a professional coach to teach Tae Kwon Do or Judo or Athletics or Music or Painting if that’s what they’re interested in …

Yes. You can. Leaving aside the question of whether it’s emotionally wise or not to expect a school to look after your children from seven in the morning until six at night every day, so what right back? That means rather than having an encouraging and well-meaning teacher giving everyone a shot even if they’re timid, shy, not very good, or a bit socially awkward your child is dependent on deciding they’re interested in a particular activity and you then being prepared to fund it. The reality is that children often don’t know what they’ll enjoy until they give it a go and they often need encouragement – not just to deal with social anxiety and peer-pressure but also the fact that learning how to hit a topspin forehand like Roger Federer or play guitar like Johnny Marr is hard and takes time and patience and help. Given also a lot of parents in this country, even ones in good jobs, are struggling financially and don’t necessarily have the money for extras, I think the encouraging and well-meaning teacher / parent / wider network model yields more results. History shows us it does, in fact. It can only happen, however, if people aren’t run ragged and have time and space to give back.

If you still think I’m over-egging the pudding and fomenting revolution and by God why isn’t the Army at York by now, go and read the account of the divergent paths Ed Smith and his sister Becky took at the age of eleven in the book Luck (2012.) Ed honestly admits that up until the age of eleven, his sister creamed him in every aspect of life: academics, sports, socialising, extracurriculars. Ed’s parents could only afford to send one of them to private school. Ed got the nod – and went on to represent Cambridge, Kent and England, scoring a century on his debut for his university, and a successful career as a writer, broadcaster and cricket selector. His sister stopped doing competitive sport at age eleven. Why? Because her state school had negligible facilities and ran no organised sports. Once Becky stopped playing at school she stopped playing anywhere. By contrast, Ed’s private school had an Olympic-sized indoor swimming pool with accompanying gym and exercise rooms; twelve rugby pitches; two hockey pitches that became twenty-two tennis courts in the season; rackets courts; fives courts and twenty cricket nets – as well as the best kept ground he ever saw until he played at Lords. It also had music and drama clubs – all things Becky later admitted she wished she’d had access to but didn’t.

So, yeah, if you’re good enough, you can get to row at Henley. But unless you know what Henley is and how you can get there and without having people to help you and without having, you know, a boat and some oars, you’ll never get the chance to find out whether you are or not.

In the podcast age, a lot of people who have been very successful tend to explain that their success in their field is down to their hard work, talent, grit and uniqueness.

It isn’t.

Everyone works hard.

Access, opportunity, luck and support are all.

People who use the example of their own lives to support their arguments should be treated with caution in my opinion, so I’ll note all independent evidence indicates that everything I’ve just said is true. Just go to the Sutton Trust website if you don’t believe me. But if you want the Oprah moment, here it is. I know the importance of all of the above because without them, I wouldn’t be writing this. Dyslexic and undiagnosed at school, I wasn’t supposed to pass exams, let alone go on to get a First. Routinely labelled thick by teachers and peers I also wasn’t supposed to do a research degree or become learned or erudite (still working on the last two). I had a stutter so bad I didn’t speak for much of my early life, so I certainly wasn’t supposed to co-found a successful podcast with one of my friends and talk about rowing with the people who inspired me to start in the first place. The youngest and smallest in my class and enthusiastic but terrible at sports, I also wasn’t supposed to develop into an athlete or row at Henley. I didn’t get to do these things because I was special and unique and brilliant (although I fairly obvious am. I’m even learning the violin [joke]). I got to do these things because I had help and support. I had family and friends and guides and teachers and mentors and coaches saying Hey, fancy giving this a go? I’ll show you how. Hey, fancy having a go at this? I’ll help. Didn’t quite get it? Well, let’s have a look at why …

The podium is a pyramid.

If we do get to stand on it, we do so on the shoulders of others.

Let’s widen this, briefly.

Seven out of every ten places in what are called the elite professions in this country are taken by people from private-educated or public school backgrounds.

Seven out of every ten places at Russell Group universities are taken by students from privately-educated or public school backgrounds.

So what? Should we penalise these students because their parents were wealthy enough to send them to a better school? Wouldn’t you do that for your children?

Of course I would. But the point is no parent should have to make that choice. The mark of a civilisation is not how well it treats its elites but how well it treats everyone.

But it isn’t a child’s fault that it’s lucky enough to be born to wealthier parents?

No, it isn’t. But it’s not a child’s fault they’re born to an absent parent or an alcoholic one either.

Ah, yes, but you’ve said it yourself. Look at Clasper. He got there. Look at Redgrave too. Britain’s most successful Olympian. He wasn’t born to money. Dickens – poor and indigent, became the greatest writer of his age. Shakespeare – glovemaker’s son from Stratford. Daley Thompson – Barnado’s Boy. There’s a long list of people who came from nothing to be successful. If you’re good enough, you’ll get there. You just have to want it.

Leaving aside that Shakespeare was obviously Edward de Vere’s literary beard, offering the example of those who made it in spite of their circumstances rather than because of them is another excuse offered by those seeking to justify inequality. It is true: everyone who is successful works hard. But for some where they might want to get to by working hard is closer and more attainable than for others. I’m also not talking about guaranteeing equality of outcome, but could we at least start by saying a child born in Britain today has a right to an equity of opportunity? Or do we really hate babies so much we want to cut their hamstrings before they’ve even started learning to walk?

It isn’t just sports, academics or professions.

Increasingly in Britain, studies show music, the arts and media are overwhelmingly populated by those who can afford to do them rather than those who might turn out to be really, really good at them.

This isn’t just unfair, it’s economic suicide.

We’re a small island in the North Atlantic.

We can’t afford to waste talent.

viii. Full Crew

It might also be said one of the major reasons for under-representation and under-participation in everything from children doing sports at school age to adults in certain professions is because it’s incredibly hard to go somewhere where it’s made clear you aren’t welcome.

Doesn’t happen in rowing? Clasper was then. This is now. We’re a meritocracy nowadays.

Remember special degree violin chap? This is our thing.

This isn’t for you. This is for us.

Yeah.

Right.

We’re a meritocracy.

After a long period of ostracism, someone I know left their High Performance programme because the coaching staff, including the Head Coach, took them to one side and told them rowing was not the sport for them. They came through one of the best junior programmes in the country, their erg scores are good and I’ve been out with them. They can move a boat. The only reason I can think of as to why this person was treated like this, then, was because of the colour of their skin. They didn’t complain – the institution would be investigating itself, which always goes well. Instead, they walked away from the sport they loved.

Another coach I’ve worked with is at a different HP centre. Despite being exceptional at their job, they get repeated comments about their background – working-class, Northern. The intake is predominantly Southern, public-school educated and wealthy. The implication? You shouldn’t be at this boat club.

Meritocracy?

Let’s say you’re a junior rower. Let’s say you have squad ambitions and you’re potentially good enough to fulfill them. Let’s say you’re from Newcastle or Carlisle. The North, in other words. The entire rowing pyramid as it has been organised points to a very particular part of the South-east. Caversham is at Reading. Leander is at Henley. British Rowing’s administrative headquarters is in London. If you want to make it, then, you have to relocate to one of the most expensive property markets in the world. Now let’s say you’re working-class or middle-class professional. Your parents might have good jobs and careers, but they can’t bankroll you or even slip you a few quid now and then. So, you go down. You sleep on a couch in a shared house and you coach and you work behind the bar at Wetherspoon’s and you do what you can to make ends meet while also trying to fit in enough training to make you competitive in one of the most successful Olympic programmes in history.

Doesn’t happen?

I know of at least a handful of rowers in the squad or on its fringes for whom that was / is their daily reality. They’ve been rowers all their lives and they really want to make a Worlds or Olympics, but their twenties are racing by, they don’t have an alternative career or plan, and they’re hanging on.

And then they make it.

They get selected.

They get funding.

Well, as Jess Varnish and many others will tell you, the funding is great until you find out you have no rights and no fall-back if anything bad happens to you, like an abusive coach or coaching system or a bad injury or a drop-off in performance.

Coaches and analysts and PA’s and administrative staff at that level have salaries, pensions, paid holidays and clearly defined employment rights.

It’s athletes who win things.

It’s athletes who put their bodies on the line.

It’s athletes who are expected to give up everything.

But it’s a meritocracy, right?

While I was writing this, someone apparently connected with 2025’s Boat Race squads put footage of a squad erg test on social media, emblazoned with the slogan if you stop, don’t bother coming back to the boat house. This person appears to be a qualified HP coach who has also appeared to work at Caversham. Their Insta page suggests you should get in touch if you feel like paying for their expertise. I’m not sure I would. I think I’d save my money because if they were as HP as they claim, they’d know crew selections aren’t made on the basis of one test. They’re made on an athlete’s body of work across a period of time across a huge amount of criteria. You’d also think they’d know if they were HP-level that if everyone who ever blew up during a squad erg test had to leave their boat house and never come back then Redgrave wouldn’t have got his fifth Olympic gold and Ed Coode wouldn’t have got his first. I wouldn’t have rowed at Henley for sure. Neither would Lewin. Or the rest of our boat, come to think of it. Ben, Sean and I once blew up so spectacularly during a test we needed a mop and bucket to clear it up.

Doing Broken Oars Podcast meant Lewin and I got to talk to some of the best to ever do it. They’ve all blown up. All of them. Eric Murray – a blonde Antipodean Viking God of an oarsman – talked about it with pride. If you hadn’t, he felt, you hadn’t gone far enough. His philosophy, which was all about being humble enough to fail, was it was better to blow up during a squad erg test so if you hit the wall with 300 to go in the Olympic Final, you’re emotionally and psychologically prepared to deal with it. You’ve been here before. Of course it’s better to complete a test well first time, but selection is made on a huge dataset. None of this looks as good on an Insta post as If you stop, don’t bother coming back to the boathouse, though.

I used to be incredibly proud of being a rower because we weren’t like other sports. We didn’t have the doping / abusive culture / athlete welfare scandals that cycling, athletics, gymnastics et al had. We did it on hard work, authenticity and integrity. Except now we don’t. The HP programmes whose success is based on a lot of socio-economic and cultural factors, but also, it turns out, toxic / abusive coaching and team cultures? Coaches leaving HP programmes by ‘mutual consent’ underpinned by rumours of inappropriate behaviours? HP programmes having reported issues with body-shaming / personal abuse cultures? I hear some of the back stories to the public reporting of these issues because I know a few people in rowing. But here’s the thing: I don’t know half as many people in rowing as the average rower / rowing person does. So if I know about this, plenty of others do too – and it’s not necessarily being called out. As a result, the things I was proud of in my sport have been replaced with cultures of entitlement and privilege. We’re winners. How we win doesn’t matter. Except it does. In the latest scandal, reported well after the fact and involving Leander, a club, incidentally, I have a huge amount of time for, someone on social media made the observation that once you have rats in your house, it’s very hard to get rid of them – to which someone added, especially if they’re medal-winning rats. Success in some of the cases noted above has excused the erosion of the values that rowing always prided itself on – and they’ll be very, very hard to regenerate, especially now that rowing in the eyes of the public has been made to look as corrupt as other sports.

This erosion, driven by a winning excuses how you won narrative, is part of the special / unique / exceptional narrative with its implicit subtext of ‘normal rules don’t apply to us. We can do what we want. We’re special.’

And it’s rubbish.

Despite having put them on a pedestal (I started rowing because of the Redgrave Four at Sydney), what came across in every Olympian Lewin and I talked to on Broken Oars podcast was not that they were invulnerable gods and goddesses who smote all in their path. It was that they had good days and bad. They felt pain. They had ups and downs. They had challenges and setbacks and adversity. They still had to do the weekly foodshop and pay their bills. All of them had strong core values about who they were and what they would and wouldn’t accept as behaviours in themselves and others, all of them were clear-eyed about what they’d achieved, but all of them were human – and being human didn’t stop them achieving extraordinary things.

Learning this made their achievements greater in my eyes.

A little while ago, I spent a lovely day messing about in a Liteboat on Derwentwater and eating ice cream with Andy Triggs-Hodge. The man has three Olympic Golds and five World Championships and was the finest stroke of his generation. I have none of these things and a finish like a rabbit leaving the safety of its burrow knowing there’s a fox about. He didn’t care. It’s a nice day. Fancy a paddle?

Yes.

Rowing isn’t just for the exceptional, the gifted, those who suffer, those who are unique, or those who have the right background and accent.

It’s for anyone who wants to get in a boat.

If you stop, don’t come back to the boathouse.

Rubbish.

It’s a nice day. Fancy a paddle?

Yes.

x. What If?

I’m sure some of you may now be screaming at the screen that someone has given an infinite number of Northern monkeys an infinite number of word processors and look what the damn things have produced. Sod the army, Millicent. We’re going nuclear. Those of you who read the Daily Mail might still be yelling that outriggers had been used before Clasper or that someone else would have invented the fine shell eventually or that it took the middle-class land grab of the Muscular Christians to organise the sport in a way those Northern Monkeys just wouldn’t have been able to do for us to get here, but those are counterfactuals. YouTube does a burgeoning trade in people saying Hitler might have won World War Two if only he hadn’t invaded Russia. You can say that, but he did and he didn’t.

So, let’s agree instead what we now have in rowing is because of all of those things. Northern Monkeys and Muscular Christians and professionalism and shamateurism and good people and bad and if you stop don’t bother coming back to the boathouse and it’s a nice day, fancy a paddle and the damned French deciding that 2000 metres was a good distance to race over.

And with that in mind, let’s play a game.

Let’s pretend if one crew started at the Island and the other started at Remenham during Regatta Week at Henley, we’d think it wasn’t fair. Everyone should start from the same place, right?

Let’s pretend also that if I’m writing this and you’re reading it we all really care about rowing and the impact it can have.

And let’s pretend those things are more important than hanging onto our own particular piece of the pie just because it’s ours and always has been, even though it hasn’t been, really.

So what, exactly, do we lose by allowing underrepresented figures of the past to be part of how we tell the story of our sport or country? Doesn’t it make it richer, more colourful story in every way?

What exactly do we lose by having a statue of Harry opposite Steve’s in Leander’s foyer? One was a coke-burner from Dunston, the other was a carpenter’s son from Marlow. Both were supreme oarsmen. They’d probably have a lot to talk about. Leander only exists in its current iteration because a history of success that was built on exclusion now means rowers from all walks of life and backgrounds want to go there. We can’t change history or the compounding effects that have contributed to its current standing. And why would we? The hippo tables are great and they do a cracking cup of coffee. Acknowledging that others did and still help it maintain its position the club would still have its exclusive aura, though, and emphasise that going forward the club is based on its continued excellence, rather than past ideas of class.

Let’s ask why does Caversham have to be at Reading? Why isn’t it on the site of the old Stella Powerstation by the Tyne at Newcastle, or by a sheltered Welsh lake? House prices and rentals would be cheaper for the athletes and staff for a start, not to mention that it levels the playing field for everyone. Rather than everything pointing to the South-east, why not be nationwide? And Newcastle’s not bad, you know. We stopped eating whippets years ago. We’ve got hot and cold running water and an airport and everything. Southern-based public-school educated athletes could come up and still attend the ballet at the Theatre Royal if they felt they were missing their native culture. Who knows, they could go out for a Bank Holiday weekend at Whitley Bay and come home with a Geordie wife and nine different children by twelve different fathers. And what would be wrong with that? Nothing. No-one batted an eyelid when Lady Harlan did it in the regency period. They just called the brood the Harleian Miscellany.

Why does British Rowing need a multi-storey townhouse on the Lower Mall as its HQ? Because it’s always been there? That’s a poor argument. Because the staff like working in central London? That’s a poor argument too. Because it’s central to everything else? That’s also a poor argument. It’s only central to everything else if everything else is in the Thames Valley.

Sell the property, put the HQ in the middle of the country. It worked for the BBC when they went to Manchester, and British Rowing’s PR Department would finally have the money to be able to pay Lewin and I for the social media campaign they asked us for pre-Tokyo Games, didn’t pay for and then passed off as their own, bless them.

And what exactly do we lose by throwing open the doors to children who’ve never even heard of rowing, let alone seen a shell or been in one? Will it take away your pride in your son or daughter competing in the Boat Race? Will it make their achievement any less special?

Of course it won’t. They’re taking part in a unique piece of ongoing English history. It’s a pageant – and life should have pageantry and colour. And it’s special. You should be able to say ‘look at my child. Aren’t they amazing?’ But you lose nothing by also looking over and saying, ‘Hey, and your child is pretty amazing too.’

If we share it, none of us loses our piece of the pie.

The pie gets bigger and there’s enough for everyone.

We get more Sam and Steve Redgraves. We get more Hodges. We get more Mums and Dads helping the club out at weekends. We get more entries at regattas and races. We get more coming through club programmes and going onto the squad. We get more participation. We get more Pinsents. We get more Claspers.

We get a healthier sport.

And who wouldn’t want that?

* * *

Nothing that was said here will change anything. Caversham will stay at Reading. British Rowing will not take the money they saved by not paying Lewin and I and start an FA Cup like competition involving every boat club on whose Finals are raced on the Tideway alongside the Boat Race, making a festival of rowing that sees Clare Balding interviewing both the five man from Jesus and the boatman from Talking Tarn on the same day. Rowing in Britain will stay much as it has done since the days of Clasper in this country in terms of cultural representation. So at best this has been something to read while you’re waiting for the kettle to boil on a Saturday morning. But that’s a shame. It doesn’t have to be that way. A long time ago in this article I tried to articulate why some people are drawn to the water and what rowing can feel like at its hardest and its best. And that’s the point beyond all of the history and the us and them. When you’re in a boat with someone, you don’t care about their background, how much money they’ve got, or what colour their skin is. You pull for them because they’re pulling for you. It could be that way instead.

And not just in rowing.

* * *

*NB: I will leave you with this thought, though: there is actually a statue of Harry Clasper. It’s in St. Mary’s Church yard, Whickham, where he’s buried. Seeing as no–one goes to Whickham unless they live there, just say the word, Leander committee and I’ll get it in the back of the van and drop it off during Henley week.

It’ll look grand opposite Steve’s.

Dr. A. I. Jackson (BA Hons (First), MA, PhD) lectured, researched and published in English Literature and English history. He rowed for Agecroft Rowing Club, Salford, competing at Henley Royal Regatta in the Thames Challenge Cup. Going on to work in Widening Participation in Higher Education for young people from non-traditional backgrounds he also co-founded and co-hosted Broken Oars Podcast with Dr. Lewin Hynes. Represented by Melanie Greer, Dr. Jackson’s account of sculling the length of the Thames, The Same River Twice, is currently under editorial. His first fiction book, Charlotte Jackson and the Magic Blanket was published in May in collaboration with Lapwing Books and is available to pre-order by contacting editor Gavin Jamieson: gmbjamieson@gmail.com. His most significant achievements are learning to row and his children. Dr. Jackson’s website is www.thelandingstage.net. All professional enquiries to: melanie@michaelgreerliteraryagency.co.uk