12 April 2025

By Aaron I. Jackson

Dramatising the incredible true story of Tyneside’s Harry Clasper, nine-time world rowing champion and the greatest sportsman of his or any other era, Ed Waugh’s classic play Hadaway Harry enjoyed its tenth-year anniversary revival earlier this year. Witnessing Jamie Brown’s powerhouse solo performance of the play, Dr. A. I. Jackson, rower, the Northern One of Broken Oars Podcast, and an academic specialist in British identities, notes the significant questions Harry’s life and Waugh’s play raised about sporting and cultural representation in Britain remain unanswered as we head into Boat Race and Regatta season in the rowing calendar.

i. A Fable Agreed Upon …

It’s likely that some of the thoughts expressed in this piece will upset some who read it. This is fine. I am largely thinking out loud, which is much the best way to think. It’s worth noting that when we do find ourselves reacting negatively to something someone has said, it’s not necessarily because of what’s said, but because it touches on a truth we don’t particularly wish to address. It can be something about ourselves that we don’t want to hear, for example, or it might be something said about something that we are deeply invested in. Our profession, perhaps, or a sport we participate in. Something, in other words, that informs our identity, either in the way we think of ourselves or the way we present ourselves to others. Something, then, like rowing. Most of us who row aren’t people who row. We don’t introduce ourselves as ‘Hi. I’m [insert name here] I row.’ There is no separation. We introduce ourselves as ‘Hi. [insert name here] I’m a rower.’ We are what we do, especially when what we do means a lot to us. As such, we tend to react protectively if we feel someone is commenting on our baby in a way we perceive to be negative. When it’s one of our own family doing it, well, God threw Adam and Eve out of the Garden of Eden for less.

‘Hi. I’m Aaron. I’m a rower. I’m also the co-founder of Broken Oars Podcast, the world’s best rowing podcast (Crossy’s Corner excluded, because we love Crossy), and a published academic in the field of Britain’s narration of its cultural identity. The first two are more important than the last.’

I’m noting this and establishing my bona fides to allay any charges that what follows is some sort of ill-conceived polemic, example of a podcaster talking poorly researched guff (we have Joe Rogan for that), bravura display of Northern chippiness (we have Manchester for that), or all of the above. Those charges will be made anyway, because that’s what happens when anyone says anything nowadays, but what’s contained in these paragraphs is not coming from these places. I love rowing and rowers in all of our many manifestations. Consider instead that any negative reaction you might have from what’s being said here challenging what you think rowing is and who rowers are.

So, to begin.

To the uninitiated, or those on the outside looking in, the representative narrative of rowing in Britain is overwhelmingly middle-class where it isn’t also public-school educated. It is the story of gentleman amateurs, the Boat Race, Henley Royal Regatta, the muscular Christianity of the late-imperial mission and a late-twentieth-century march to Olympic glory against a backdrop of the South-East, the Thames Valley and its river. Like all dominant cultural narratives, these things are foregrounded because they represent the background and history of those doing the writing. At the time I began writing we were scant weeks away from Oxford and Cambridge’s annual meeting, for example, and already copy and commentary were being generated touching on all the above ideas: that the institutions and individuals involved represent something Corinthian and noble and true; that their educational background somehow marks them as something special; and that their sporting contest reflects this.

Even though this clamour will intensify as we march towards the contest on the Tideway the simple reality is none of the above is accurate. When it comes to the Boat Race, often full internationals ticking off a personal bucketlist bulletpoint nowadays, especially in a fallow part of the Olympic cycle, those training for it while also studying are no more or less Corinthian than any club rower fitting a session in before work. Part of a massive commercial enterprise and supported personally and professionally in a way many professional athletes can still only dream of nor do these athletes love rowing or represent its ‘spirit’ somehow more truly or nobly than anyone else. It could accurately be argued that the provincial club stalwart keeping an entire junior programme going by themselves and paying for the launch outboard to be mended out of their own pocket is doing something just as true, noble and selfless. They also do it for no pay as well, but there are no broadcasters and commentators queuing up to interview them about their Corinthianism. Beyond that, it’s also fair to note that rowing takes place in some form on every river and body of water in the UK capable of bearing a boat, not just the Thames; and that rowers come from as many backgrounds as there are in the UK, not just public schools.

Yet despite being demonstrably untrue, these views about our sport remain perniciously clung to. As part of Broken Oars Podcast, I found myself embroiled in a social media exchange last year with an accredited Boat Race commentator determined to assert that the doctoral research project of one of the participants marked them as being ‘special.’ Explicitly trotting out the idea that a qualification from Oxford and Cambridge was somehow worth more than a qualification from any other HE institution, they were oblivious to the fact that this is simply not the case: a degree at any level in the UK is worth the same educationally and professionally as a matter of legal fact as a degree from anywhere else in the UK and is assessed and awarded on fuflilment of the same agreed criteria. Culturally, of course, it isn’t – but that’s the point. What was stunning was not the ignorance of this commentator – we all have gaps in our knowledge, after all – but their determination to cleave to their position in the face both of the evidence and the fact they were talking to a university lecturer, published academic and examiner who actually knew what they were talking about. I simply disengaged when they went on to suggest that being able to play the violin meant someone else brought a lot to their boat. I have strong views about the overlaps between being a musician and being a rower. I’m both, and all evidence shows that they share the same physiological and psychological skillsets, learning curves and performance criteria. So I probably would have agreed with them on that point, but my Grandfather once gave me the advice that it was a waste of time arguing with children or bigots. Being young and foolish at the time, it took me longer than it should have to realise he was right. You can’t. You let the former scream themselves out and walk away from the latter. And so when the violin came out (in every way), I walked.

The above anecdote from last year’s Boat Race may be a synecdochal example. It also took place before this year’s idiocy regarding the eligibility of PGCE candidates for selection – which reflects less on the academic worthiness of postgraduate qualifications and more on the determination of some to weight the race in their favour by an interpretation of the rules that precedent shows is ill-informed at best and the act of weasels at worst. Don’t be a twat. Plenty of PGCE students have taken place in the Boat Race in the past. However, to come back to the main thrust of this section, it is not unfair to suggest that invested in its own representative history and supported by the consolidation of administrative and institutional power in one specific geographical and cultural locale, British Rowing keeps telling the same story as if it was ever thus and ever will be even when it wasn’t and it isn’t.

ii. Aquatics, Watermen, Harry Clasper and History

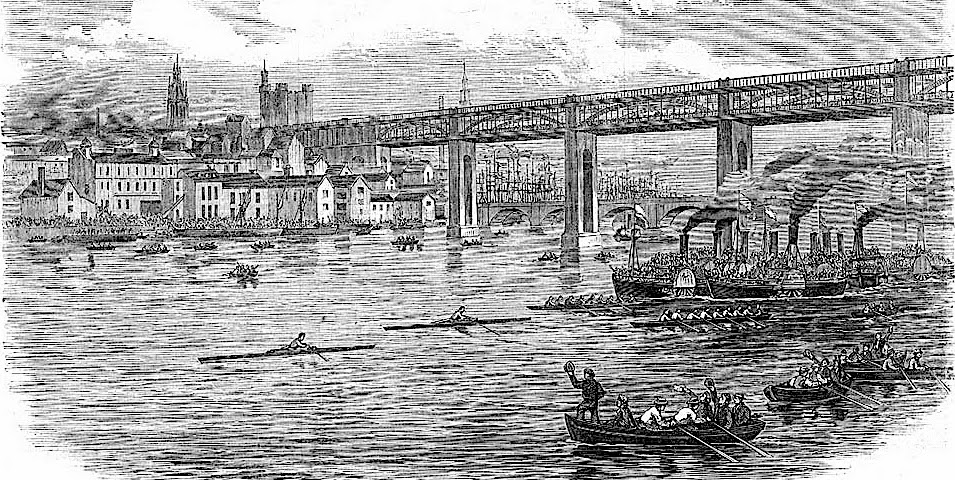

In actuality, rowing’s origins go back to the time when the rivers of Britain were its major transport infrastructure, with contests and systems of racing evolving alongside these realities to allow those who lived and worked on the water to establish who were the best watermen. Coinciding with a growing urban population, the period after the Industrial Revolution saw the sport and racing grow and develop exponentially at local and national levels. Contests regularly drew tens of thousands of spectators to riverbanks all over the country, with those who established themselves as the best of their region going on to challenge the champions of another. Prestige was at stake. So too was prize money. This was also, finally, the period of Britain’s emergence as the world’s leading imperial power, which meant that those who were crowned champions of England in any given sport were seen as being the champions of the world. Holding true in everything from boxing to footracing, it was a conceit that extended to rowing. At this point, before the rise of mid-Victorian shamateurism co-opted them, rowing was like cricket, boxing, horse-racing, the early iterations of football, athletics and cycling and other now-forgotten British sports like rat-catching, bear-baiting, dog-fighting, archery, wrestling, single-stick, backswording and putting small children up chimneys: fiercely contested, often heavily gambled on, full of sharp practice and practitioners, chancers and ne’er do wells and predominantly featuring working-class participants.

I was aware of these realities, of course, just as I was aware of the ways that the British middle and upper classes overwrote them with their own versions of events – so successfully that we’re still repeating them as truths today. These narratives and the processes that formed them were a significant part of my doctoral research and academic field. I’ve never particularly minded that this overwriting happened, by the way. It happens in every culture and its human nature to tell a story in the way that shows you in your best light. Attending a recent performance of Hadaway Harry, Ed Waugh’s play about the North-east’s world rowing champion Harry Clasper, made me reconsider these overlapping historical and cultural contexts however. It also made me consider that it would be fair to argue that the perpetuation of these cultural narratives explains why British Rowing still has the image it has and why it has participation issues that won’t change until they’re rebalanced. We will come to these ideas in time, but let’s start first with them also being the contexts in which the life and achievements of Harry Clasper must be placed.

By any standards both are remarkable. In our age of by-the-numbers sporting memoirs, social media fitness influencers repeating glib coaching mantras and sports documentaries that have rendered remarkable human achievements into predictable arcs marked by familiar beats, Clasper’s story is, however, extraordinary. It is extraordinary not because he was successful but because he was not supposed to succeed – and yet he did.

Born the son of a miner in the North-east of England in 1812 and a bonded mining apprentice, Clasper escaped a preordained life of back-breaking work and grinding poverty via what were then known as ‘aquatics’ to become among the most celebrated champions of his age in any sport. Nine times world champion, a skilled waterman and a master boatbuilder, Clasper’s innovations in the latter are also the bedrock on which modern rowing rests: the development of the fine racing shell concept via his groundbreaking designs for his own Five Brothers and Lord Ravensworth boats; the use and refinement of outriggers and the incorporation of legs and swing into the drive phase to increase stroke length, leverage against the pin and run between strokes. Aided by liberal applications of grease to leathered shorts to allow sliding back and forth on the wooden seats of the boat to allow more leverage against the footplate, this created the Tyne stroke which became as much a commentated wonder of the age as his boat designs: the stranger to London aquatics who wishes to see the river at its best should select one of the championship races between professional scullers, especially if London and Newcastle are pitted against each other (Charles Dickens). While it would be too much to claim that Clasper created periodised training as modern rowers might understand it, Clasper’s training regimen should be eerily familiar to anyone currently participating in the sport at levels from senior club to squad:

6:30 am: Warm-up. Five mile walk. 8:00 am: Breakfast: mutton chop or two fresh eggs. 9-00 am: Run. 10:00 am: First outing. Midday: Dinner: beef or mutton, broiled or griddled. Light egg pudding. One glass of beer or port wine. 1:00 pm: Second outing. 3:00 pm: Put to bed to sweat in heavy clothes. 4pm: Massaged and left to cool down. 5:00 pm: Tea: tea and toast. One egg. Anymore than one clogs the system. Rest. Supper: new milk and bread. One glass of port wine. 10:00 pm: Bed.

Up to four sessions a day, then, with land-based training incorporated next to a minimum of two water sessions where mileage and intensity were contrasted with focus on technical application and crew cohesion. For modern core and activation work, read the interspersed rub-downs, massages and ‘sweats’, and note the emphasis being placed on good, clean nutrition to feed the engine. Pretty familiar, really. Unlike modern rowers, however, Harry didn’t train like this for months on end, his hands bleeding on the oars, with Henley Royal or Olympic glory in mind. He trained like this because he was a professional oarsman: he won, or he went back to the cokeworks or back down the pit – the same pits he’d started in as a boy, the same pits where bonded men were indentured and owned by the pit owner like slaves and valued less than pit ponies long after the other slaves in the British Empire had been freed. In my lifetime, the refrain from generations of politicians has consistently been that Britons need to work longer and harder, despite all independent evidence showing that in the same period the British have worked longer hours (and yet with less productivity) than any other comparable country. It is difficult not to conclude that some will only be satisfied until we’ve returned to Clasper’s day – a place, in other words, where children younger than mine now worked 18 hour days and where life expectancy was middle thirties if you were lucky and if firedamp, cave-ins, mechanical failures, black lung or simply starving to death because you were too ill to work didn’t kill you first.

The water, then, was Harry Clasper’s way out – and he took it to the extent that by the time he died he was one of the most successful sportsmen in British history; had been immortalised in one of the few folk songs from any part of the UK known by everyone from Lands End to John O’Groats in The Blaydon Races; and was a man of substance and means. At a time when Newcastle’s population was numbered between forty and fifty thousand, what is salutary is not that tens of thousands turned out to watch Harry race on their days off, but that the factories and works of the region fell silent and 130,000 men, women and children were estimated to have attended his funeral on the day. So many turned out, in fact, that it took over eight hours to get his coffin and cortege from the middle of Newcastle and down Grey’s Street to the Quayside – a distance of about a mile and a half. An inspiration in life, Harry was mourned in death not just by his family and friends, which is the best most of us can hope for, but an entire region.

iii. Hadaway Harry

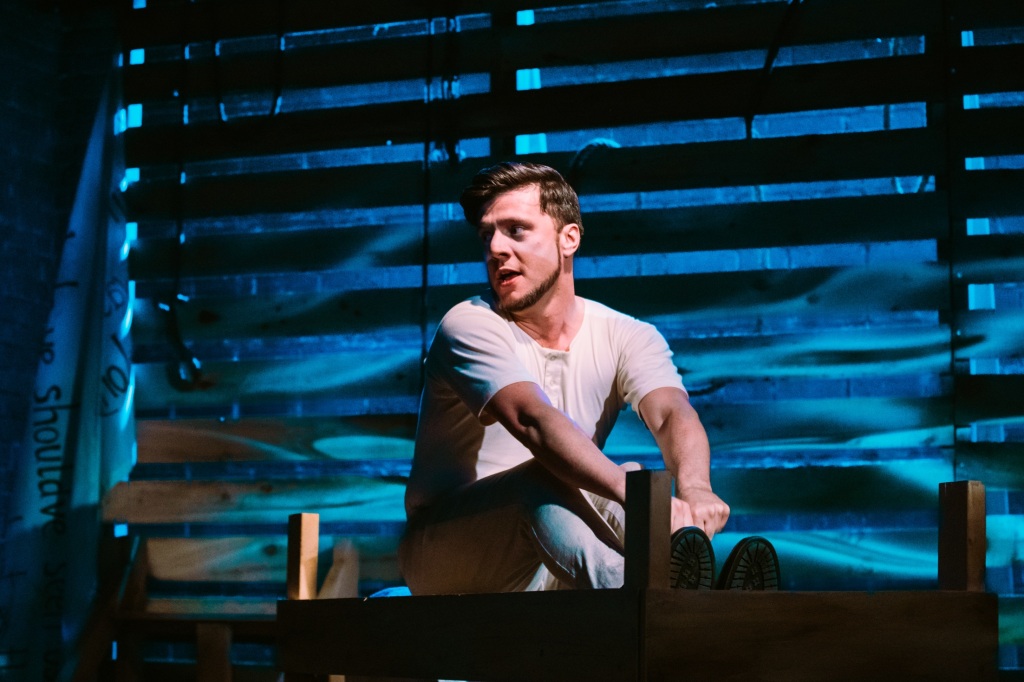

All of this is detailed in Ed Waugh’s Hadaway Harry. One of Waugh’s triumvirate of studies of North-eastern icons, the play recently enjoyed an extended run in civic theatres and boathouses in the region to mark the tenth anniversary of its first performances. Waugh’s play, superb production, and a bravura central solo performance by Jamie Brown as Clasper and all other characters all combine to rescue Clasper from being a historical footnote by bringing him, his life and times, and his impact and importance to vivid, stirring and inspiring life.

I attended the play during this run at Gosforth Civic Theatre. Part of a once thriving network of regional local performance spaces that have largely been sent to the wall over two decades of determinedly making the Arts something only those with time and money can do, Gosforth’s theatre is a comfortable hub whose good cafe draws locals in for a coffee and whose rooms offer performers and groups operating below star level a place to gig, workshop and run classes and courses.

The staging is minimal, but evocative. The rise of social media platforms and podcasts have made us familiar with the idea of the one-man show, but it is perhaps worth noting this isn’t the Q and A format of touring celebrities retelling already shop-worn anecdotes at the prompting of a straight man stooge. Hadaway Harry is theatre at its simplest and most challenging. The set is uncomplicated – slatted offset backboards, a trunk doubling as a lectern, and a square box-like structure that sometimes doubles as a bed or a boat. Lighting is minimal, but effective in emphasising shifts in location, mood and tone, with an occasional voice-overs, sound effects or images used to set or intensify the scene.

Simple, then, but challenging as one actor has to bring to life Clasper and play and embody all other characters using glove puppets – all the while taking the audience from the pit of Harry’s early life to the pinnacle of winning the world rowing championship. Step forward Jamie Brown. This last, achieved in real time, is a theatrical tour-de-force that owes its dramatic impact to Waugh’s play compellingly outlining the challenges and setbacks Clasper faced on his quest and Jamie Brown’s superb, committed portrayal of the same. Most of us would like to do something noteworthy in our lives, perhaps achieving something of importance that might be remembered beyond us. Whatever Jamie Brown goes on to do beyond this, and he should be wished every success, this may be his white stone. Over the last decade, Gateshead-born Brown has made the role of Clasper his own, inhabiting the man so thoroughly and with such full-throated passion that the audience lives every moment of Harry’s journey and feels every emotion – pride, hope, happiness, crushing disappointment, determination, resilience, love, grief, passion, ambition – until the final glorious apotheosis when Harry realises his goal, made sweeter by his family being in the boat with him. This is a career-defining landmark portrayal.

IV. As One …

Given the framing of this article, those expecting a polemic might be wondering when it’s coming, especially if you’re also thinking that a review of a theatrical performance involving a niche sport isn’t going to change much with regard to cultural representation, or socio-cultural or economic realities in Britain, as my esteemed colleague Dr. Lewin Hynes, the Southern One on Broken Oars Podcast, would undoubtedly argue. So, here’s the first thing you should take away from reading this far – besides the idea that the Harrying of the North didn’t go far enough and it might be time to send the troops North of York again sometime soon because those Northern monkeys of our are getting damned uppity, hey?

Here it is:

If you want to understand why your son or your daughter or your friend or your family member rows, go and see Hadaway Harry.

Here’s why:

We are inundated with narratives telling us how and why people do sports now. Documentaries, memoirs, self-help books, social media, podcasts about everything from football, basketball, rugby, athletics, boxing and tennis … To a fault even the best of these emphasise two things: exceptionalism and suffering. We are told how hard this is, how hard those involve work, and how difficult it is to achieve sporting glory. We are told this because, by extension, that tells us that those involved are special, rare and unique. Rowing is as guilty of this as anyone. Whether it’s Gold Fever, A Golden Age, a Boat Race commentator, one of the late-Victorians or someone’s socials, what tends to be foregrounded are the pain, the sacrifice, the difficulty and the suffering, and the specialness of all involved.

That those who are exceptional suffer and suffering is the way to being exceptional is utter nonsense, of course. The average sportsman or woman isn’t working any harder than a minimum wage worker cleaning a corporate office at three am before going on to their second or third job, or a cancer care nurse, or a teacher, or someone on the tills at Tesco. Nor are they doing anything more important than them or suffering anymore than them either. If anything, if you’re lucky enough to earn a living from playing a game or exercising professionally chances are you’re doing something you want to do, which most of us don’t always get to, and which physiology, opportunity, luck and support have suited you for. The podium is a pyramid. If we do get to stand on it, we do so on the shoulders of others. The idea of exceptionalism being rewarded after enduring adversity is a narrative trick, one driven by ego and the premium society places on sport.

Further to this, in my experience, which is that of a fairly good club rower lucky enough to be at a good club in Agecroft with outstanding coaches who knew what they were doing and far better oarsmen than I ever could be around me, rowers don’t row because we enjoy pain. We row for all sorts of reasons, but those reasons all feed into the reality we row because we’re drawn to the simple but incredibly hard act of moving a boat well through water. Something in the sport, in its discipline and challenges, in its structure and communities speaks to us as individuals. Something in the challenge of mastering the art of rowing resonates with us and gives us something that nothing else in life does. The feeling we get when it clicks, ultimately, is one of communion: with ourselves, with our crewmates; with the water; and with the feelings those give us. Is there pain? Of course there is. A fully committed 2k hurts like hell. Even 21k steady-state UT2 @r18 isn’t exactly a barrel of laughs. But any pain we suffer is voluntary. It is the price we pay for being able to do what we love, not the reward.

I mention this because the second act of Hadaway Harry and Brown’s performance of the pivotal, climactic race against Robert Coombes’ Thames watermen does a better job of viscerally communicating what rowing feels like and why rowers do it than anything else I’ve experienced outside of actually doing it. Others may nominate something different. But having read every rowing memoir I can lay my hands on, ghostwritten or no, and seen every movie ever committed to tape that places the sport front and centre, Waugh and Brown nail it – and not just in a way that only I could recognise as a rower.

Two years ago, I took my family to see the play at Hexham’s Queens Hall – another provincial venue hanging on thanks to volunteers, creative programming, and strong ties to its local community. As the race unfolded in front of them, my Mother clutched my arm tighter and tighter and tighter until the climactic end. Tension and arm released, she leaned into me and whispered Is that what it feels like? I nodded, unable to speak, having relived through Brown’s performance and Waugh’s words my own experiences on rivers from the Tyne to the Tideway. It’s worth noting that my Mother has run more marathons than I ever will and still does daily Yoga at seventy-five, so she’s not exactly unaware of what goes into an athletic life. But it’s equally fair to say that she and my family have seen me win at Rutherford as fastest boat on the day and lose quite heavily at Henley. They’ve been supportive without fully understanding why I would wake before dawn, before work, go training and then do another session at night. That was the day they got it.

Why do we do it?

Because.

We have all seen images of rowers, slumped over their oars at the end of hard races, their faces creased with pain. Only we as individuals know if we are performing theatrical gasps and grimaces for the rest of our crew, our coach and the crowd to show how hard we’ve worked and how much we’ve suffered or whether we have no choice in the matter: we’ve pulled so hard for our boat and our crew that our blood has been replaced by acid, our heart is beating like a racing steam engine’s pistons, our lungs are burning as if the air we’re breathing is poison and our abdominal muscles are cramping so hard they’re creasing us over our oar.

Rowing, then, reveals character.

It shows us who we really are, not who we pretend to be.

It shows what we really think of the people around us, and what we’re prepared to do in their service.

And it shows us who we can become, too.

Why do that?

Why put ourselves through that?

After all, I’ve just said that rowing isn’t about the narrative of suffering it’s often cloaked in and then just listed how it hurts.

Because.

Because at its very best, rowing isn’t a sport. It’s a spiritual experience. It means nothing, in real terms. We have outboard motors and bridges now. We don’t need rowers. So, it’s pointless. It is a deed quite literally being written in water. But to those of us who take part, it’s not something we do. It’s someone we are. And in that moment, the moment so vividly portrayed by Brown when Clasper has the choice of stopping in extremis or reaching forward and taking another stroke, we too have the same choice – in the boat and in life. When Clasper does come forward and takes the next stroke, despite every fibre of his being screaming at him to stop, he does so out of love: for his crewmates, for the Lord Ravensworth, for his brother Edward, for his family, for his home, for his wife and children, for the water, for the challenge, for difficulties overcome and hard skills mastered … and his love is rewarded by the sheer bubbling sense of joy a boat and a crew really moving well gives you: it is life, it is youth, it is, as Peter once said, the little bird who has broken out of the egg. It is what a North Atlantic salmon being drawn back to their home river after years at sea must feel: the inevitable, inexorable, unstoppable force of life itself.

That’s what rowers feel.

And that’s why we do it.

It wasn’t just me who felt it. Looking around two years ago and again recently at Gosforth, there were grown adults who’d never been near a boat in the lives gasping for breath at the race’s end. Others had tears streaming down their faces.

Yes, I was one of them.

I always was a soft shite.

Your son doesn’t row because he enjoys pain.

Your daughter doesn’t row because she wants to suffer.

Your Mum or Dad isn’t still turning out for the Masters because they enjoy wincing when they stand up.

Rowers row because it gives us nothing else life can – and in doing so, it informs how we live the other parts of our lives.

And if you want to understand that, go and see Hadaway Harry. It’ll tell you more than a million Boat Races and their commentators ever will about the sport and why we do what we do on the Tideway, and every other river in the land.

Part II of Aaron Jackson’s article will be published soon.

Dr. A. I. Jackson (BA Hons (First), MA, PhD) lectured, researched and published in English Literature and English history. He rowed for Agecroft Rowing Club, Salford, competing at Henley Royal Regatta in the Thames Challenge Cup. Going on to work in Widening Participation in Higher Education for young people from non-traditional backgrounds he also co-founded and co-hosted Broken Oars Podcast with Dr. Lewin Hynes. Represented by Melanie Greer, Dr. Jackson’s account of sculling the length of the Thames, The Same River Twice, is currently under editorial. His first fiction book, Charlotte Jackson and the Magic Blanket is being published in collaboration with Lapwing Books and is available to pre-order by contacting editor Gavin Jamieson: gmbjamieson@gmail.com. His most significant achievements are learning to row and his children. Dr. Jackson’s website is www.thelandingstage.net. All professional enquiries to: melanie@michaelgreerliteraryagency.co.uk