27 February 2025

By Edward H. Jones

Edward H. Jones, who on February 3 told the story of the African American professional sculler Frenchy A. Johnson, writes about an eyewitness account of “The Great International University Boat Race” between Harvard and Oxford Universities on the River Thames in 1869.

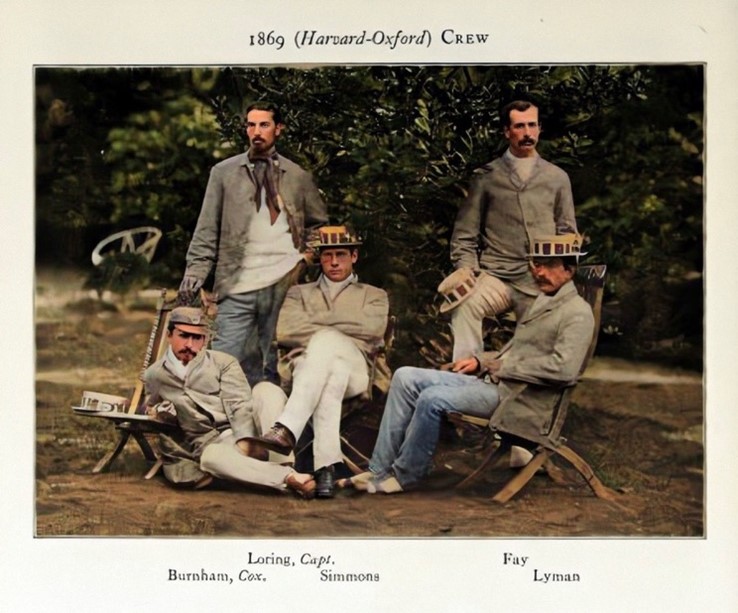

In the archives of Harvard University is a six-page, handwritten (in pencil), eyewitness account of what has become known as “The Great International University Boat Race” on the River Thames (England) between Harvard and Oxford Universities on August 27, 1869. The account was written by Willian Rotch, Harvard class of 1865, and it was donated to Harvard in 1956 by Rotch’s daughter, Mrs. Channing Frothingham, née Clara Morgan Rotch. At Harvard, William Rotch had received a Bachelor of Arts degree in civil engineering not long after the end of the American Civil War. In 1869, Rotch was furthering his studies in Paris when he decided to cross the English Channel to observe the crew from his alma mater compete against the Oxfords in coxed fours in what would be dubbed “the greatest race ever contested on the Thames.” Much has been written about the Harvard-Oxford Boat Race, including two essays posted on HTBS: “When The Crimson Met The Blue” by Chris Dodd (August 27, 2019) and “Deja Vue All Over Again” by Tom Weil (September 10, 2019). Bill Miller has also published an essay on the race between Harvard and Oxford on his website Friends of Rowing History – “The Great International Boat Race”.

Accordingly, I won’t attempt to describe the race in any detail except to say that according to an account in the New York Times, it was estimated that more than one million spectators had gathered along, floated upon, and perched above the Thames to witness the four-mile race from Putney to Mortlake. The following is a verbatim transcription of Rotch’s handwritten account interspersed with images pertinent to the event and commentary by me (EJ) where I conclude by postulating the likely reason for Harvard’s loss to Oxford.

Oxford – Harvard Boat Race

Defeated, but not disgraced, the Harvard four passed the winning post at Mortlake yesterday afternoon six seconds after their victorious opponents the Oxonians, whose time was 22 minutes and 41 seconds over the 4 miles & 3/8 from Putney to Mortlake _ They were probably as much surprised as any of their friends or any of the persons who observed the race during the first two miles, for they had fully expected to win the race, and would have done it had it not been for a most unfortunate circumstance, which can be attributed only to bad luck, or to too much zeal in training _ But nothing should be said to take away the honor of Oxford’s victory which was perfectly fair & well won _ The unfortunate circumstance was this. Loring _ the stroke oar, the most important man in the boat, and the best oar when he is in good condition had been suffering for several days from a painful boil on his cheek, which had kept him awake for three nights before the race, and it was evident to any one who saw him that he was hardly in a condition to row a four mile race. But Loring could not bear the idea of giving up, although it would have been better had he done so, and he endeavored to convince himself, as well as other people, that he was feeling almost as well as ever _

EJ – Although a cheek boil might seem like an insignificant malady that shouldn’t significantly impair a rower’s ability to pull an oar, it should be remembered that penicillin wouldn’t become commonplace until the onset of World War II. The boil that afflicted Alden Loring, the Harvard stroke, was apparently such a debilitating infection that it was described in the press as “angry,” and the infection could have been accompanied by a fever which would have amplified his discomfort. In short, Loring simply was in no condition to race as would be shown.

So the race began, and Harvard easily took the lead gradually drawing away from the Oxford boat, each stroke carrying them further in advance, so that everybody who saw the first part of the race felt sure that the magenta would arrive first at Mortlake _

EJ – Before Harvard settled on crimson as its official school color, magenta had a brief stint as the chosen hue. According to a letter from a Harvard graduate cited in The H Book of Harvard Athletics (1923), the letter writer noted that “the hat bands worn by the Harvard four that went to England in 1869 are without a doubt magenta.” In addition, newspapers reporting on the Harvard-Oxford boat race at the time confirmed that magenta was indeed the color associated with the Harvard crew. Later in The H Book of Harvard Athletics the editor writes “From the foregoing it would, we think, appear to be established that the original Harvard color was crimson but that owning to the prevalence of the fashion for magenta between the years 1860 and 1864 and the inability of the members of the various athletic teams to procure crimson for their insignia, magenta was, of necessity, accepted as a poor substitute which, with the rapid passing of college generations, soon came to be regarded as the regular Harvard color until 1875 when the University met in protest and readopted the original crimson, which has remained Harvard’s to the present day.”

The English were in great consternation, for they had never seen the favorite Oxford crew lose ground so fast, and although before the race they were offering 2 to 1 on Oxford, they were now demanding odds for the dark blue. The Harvards drew gradually away from their English rivals, and at the end of two miles they had put a boat’s length of clear water between the magenta and the blue. But here Loring’s strength began to fail him, and although he had begun with 46 strokes a minute, he gradually diminished his stroke to 44, 42, 40 and at last 37, so that the Oxford boat was able to regain a length, and her bow had almost lapped the Harvard’s stern. Lyman, who was pulling No. 3, told me that he felt the boat dragging more & more as if there was a dead weight on his side, and although he pulled with all his might, the bow side was too strong for him, and the boat swerved round across the track of the Oxfords. A foul in these conditions would have been decided against Harvard, and Burnham, our coxswain, turned his rudder sharp round the other way, and before he could bring our boat again in line, she had described a perfect S, and the Oxford coxswain, who had kept on in the straight course, brought his boat up even with the Harvards. The Hammersmith bridge, (about two fifths of the course) was passed by the Harvards three quarters of a length ahead, in the extraordinary time of 8 minutes & 30 seconds _

It was just beyond the bridge that the boats were even, and then, as three of our men were doing the work of four, they had the mortification of seeing the Oxfords draw gradually ahead of them_ Lorning grew very pale, and on three occasions Burnham was obliged to drop his tiller ropes, and dash water in Loring’s face.

EJ – Race day was reportedly the warmest of the season with the temperature rising to 95°F and the sun “broiling” down on everyone in attendance. If Loring did have a fever, that fact, coupled with the day’s heat as well as the Harvard coxswain dropping the steering tiller ropes so he could splash water on Loring’s face, would easily explain how the Harvard boat ended up drifting off course, thus losing valuable seconds and allowing the Oxfords to gain on the Harvard boat and eventually overtake it.

Some newspapers, such as the New York Times and The Times of London, listed the boat seat position numbers increasing from stroke (#1) to bow (#4) rather than from bow (#1) to stroke (#4) as they would be listed today (perhaps HTBS readers might know why). This is why William Rotch in his account referred to Harvard’s Francis Lyman as the 3 seat (the 2 seat today) who indicated he could feel the strength of his bowman who sat directly behind him.

It was just at this time that the two boats came in sight of where I was, and the Harvards seemed to be going wide of the course, allowing the Oxonians to gain upon them gradually, so that they passed the place where I was four lengths ahead of the Harvards. There were several Americans at this place, and the few cheers which they sent up, seemed to cheer up the Harvard crew, and especially Loring, who quickened his stroke to 40 or 41. The boat darted forward, and the Harvards bent to their work, as if determined to regain the lost ground. Slowly, but surely they approached the winning boat, but four lengths was too much to make up in a mile, and the dark blue crew passed the judge’s boat, with just half a length of clear water between their boat and that of the Harvards.

It was a glorious race, and the losers deserve almost as much praise as the winners. The course was kept clean all the way, and perfect justice was shown to the Harvard crew. The Oxford crew said they never saw such pluck and determination, and they thought the last mile would never come to an end; they said it was the hardest race they ever pulled, and this was proved by the fact that the Harvard crew reached the Hammersmith bridge in the shortest time on record _ 8 minutes & 30 seconds, and that they were only 6 seconds behind the Oxfords at Mortlake _

Everybody hopes that next year the Oxford crew will visit America; if they do, I think the race will be even closer than this year, for the Harvards will stand a better chance on smooth water, and a straight course, where more depends on the rowers, and less on the coxswain _ Nil desperandum!

EJ – Notwithstanding the Latin phrasing for “Not to despair,” or in other words, “Wait till next year,” next year never came. Harvard would never again race Oxford in a strictly dual boat match – not in England, not in America. Alden Loring, the Harvard stroke and crew captain, was described as the ideal Harvard oarsman who had been long regarded by boating men as “one of the most thorough and accomplished amateurs in America” and was considered Harvard’s “most skillful and experienced oarsman.” Considering that Harvard lost by a mere six seconds with an ailing Loring at stroke, a healthy Loring would have surely resulted in a victory for the Harvards. Based on William Rotch’s eyewitness account above, Loring’s heroic but ill-advised insistence on rowing when he was clearly in no condition to row unfortunately resulted in him unwittingly sowing the seeds of Harvard’s defeat.

This is a wonderful story of an historic race with the Willian Rotch narrative. Having in my youth been a coxswain on the Tideway, the last sentence, “for the Harvards will stand a better chance on smooth water, and a straight course, where more depends on the rowers, and less on the coxswain.” was particularly apt. Although the river and Hammersmith Bridge were different back in 1869 the basics for the bend approaching the Bridge remain similar. As the Harvard boat was in the lead with clear water it must have been closer to the Surrey shore, then when it looked “as described” there was going to be a foul the only course would be to move out of the faster water towards the Middlesex shore “describing a perfect S”, all enough to then allow Oxford to crossover in clear water along Chiswick Reach for the turn towards Barnes Railway Bridge. Harvard had other problems but that unfortunate circumstance under Hammersmith Bridge sealed the situation for Oxford. Notwithstanding the steering skills required for Head of the Charles, for me, it is a pity there are not more top level races where the coxswain is more than just a time keeper and vocal coach.

Sincerely,

David Godfrey

Del Mar, CA