18 February 2025

By William O’Chee

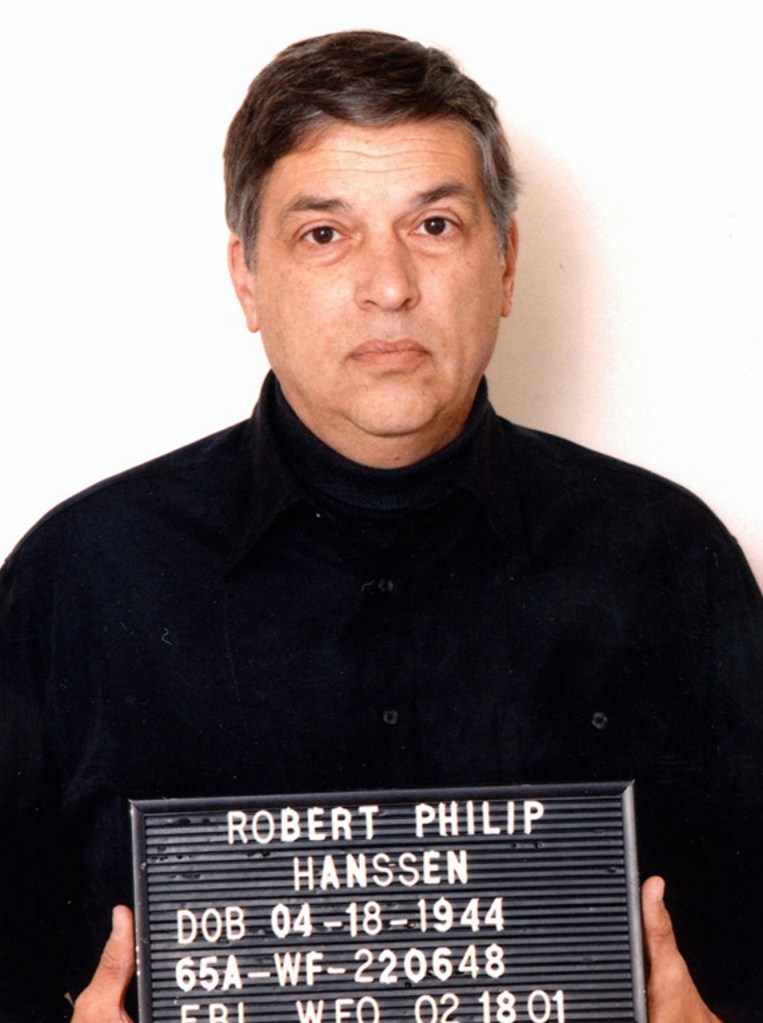

On the evening of the 18th February 2001, FBI Special Agent Robert Hanssen parked his car by the entrance to Foxstone Park, Virginia, which is near Washington DC. Hanssen spent only a few minutes in the park during which time he left a package wrapped in a garbage bag under a bridge.

Emerging from the park, he was surrounded by FBI officers and a SWAT team, and arrested. Hanssen had taken his last steps as a free man.

The package Hanssen placed under the bridge was a treasure trove of American secrets left at what was intended to be a KGB dead drop. Hanssen pleaded guilty under a deal which spared him the death penalty but left him to languish as a traitor for the rest of his life in a federal prison. He died of colon cancer on the 5th June 2023.

Many of those Hanssen betrayed to the Russians were not so fortunate. Over two decades of spying for the GRU and the KGB, Hanssen had given away the identities of hundreds of US intelligence assets – a euphemism for secret agents – as well as details of many highly secret programmes. The fate of those he betrayed was usually a bullet to the back of the head.

I recently read Gray Day by Eric O’Neill, the FBI officer who played a crucial role in helping snare Hanssen. O’Neill was a surveillance officer who was brought in from the field to FBI Headquarters to secretly spy on Hanssen in a sting operation in which they ostensibly worked together to establish an FBI Information Assurance Team.

When they first met, Hanssen was dragging a rowing machine into his new office. O’Neill referred to it as an exercise machine, which drew a curt rebuke from Hanssen. “It’s a rowing machine. I row,” O’Neill remembered him saying.

This struck me as highly peculiar. What serious rower would want to row on an ergometer in a small office in the middle of the FBI’s headquarters building?

However, beyond this, I wracked my brains to think of anyone who had betrayed their country, who had been a rower. I could think of none.

As Dan Lyons, a former US Olympic rower and World Champion in the coxless four, explained to me:

“Rowers row for a great many reasons. No matter what brings them to the sport however, they all leave with one thing in common; an unbreakable bond of shared experiences that define the very concept of loyalty.”

Certainly, many rowers have served their nations with distinction as secret agents (spies) or as intelligence officers (spy masters, agent handlers or analysts). My mind immediately goes to Rupert Raw, the Etonian and Oxford Trial Eights oarsman whose charm and courage as an SOE agent in WWII would have put even James Bond to shame.

Then, of course, there was Sir Douglas Dodds-Parker, the son of an Oxford Blue, and himself Captain of Boats at Magdalen College, Oxford, who helped Emperor Haile Selassie return to the Ethiopian throne in a daring SOE mission in 1941. He then played an important role in planning “Operation Anthropoid”, the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, a leading Nazi, before Dodds-Parker rose to be a senior SOE spymaster.

I am currently researching the WWII service of ten Oxford Blues and Trial Eights men who may have given secret service in the SOE. They were all incredibly brave, but none was a traitor. In fact, in both World Wars, Oxford and Cambridge oarsmen (and I am sure oarsmen at many other universities as well), were far more likely to lay down their lives for their country than most.

So, if rowers are by nature loyal and very unlikely to betray their country, what made Robert Hanssen different? The answer may be that Hanssen was never a rower in the first place.

Eric O’Neill told me: “Hanssen’s ‘rowing’ was limited to the small rowing machine he brought to his office, and I suspect that most of that was optics rather than exercise. To my knowledge, he was never a rower in a boat club or team.”

This seems to be the case. I contacted every rowing club in the DC area, as well as every school rowing programme, and none said that Hanssen had been one of their rowers, nor a coach.

If Hanssen never rowed, then why the charade? In his book, O’Neill documented the many times Hanssen would try to throw him off balance, either physically or psychologically. Pretending to be a rower seems to somehow have been part of this course of conduct.

None of this should be a surprise. Hanssen spent decades living a life characterised more by deceit than truth. He pretended to be a devoted family man, but was prosecuting a long term relationship with a stripper. He pretended to be a loyal FBI agent, but betrayed all his nation did. He pretended to be a Catholic who believed in the sanctity of life yet sent countless people to their deaths. And he pretended to be a rower.

As Dan Lyons reminded me: “A traitor to their nation eschews the ties of loyalty carefully nurtured from birth and substitutes for them personal ego and ambition oftentimes wrapped in a package of poorly understood promises.”

So, what happened to the rowing machine? I’ll leave that to Eric O’Neill.

“I can’t recall the model of the rower, but we found a very similar one that we used in the movie breach. It was small and obviously portable and rather flimsy. As far as I know, the rowing machine was left behind in his office and likely scooped up as a trophy for some enterprising agent,” he told me.

And with that all trace of Hanssen’s rowing career was gone.

If you want to know more about Eric O’Neill’s role in catching perhaps the worst traitor in American history, purchase a copy of Gray Day (2019), ISBN 978-0525573524, from a good bookstore near you.