21 January 2025

By Matthias Zander

(All photographs from the archives of the Berliner Ruder-Club)

In December 2014, Greg Denieffe wrote an article about the 1902 regatta in Cork and the crew of the Berliner Ruder-Club. At the regatta, the German eight lost the final to Leander. As a Berliner, I would like to add a few things to this story as, to this day, the regatta is not forgotten by the Berliner Ruder-Club, and it harbours a lot of stories that should be told.

The club’s chronicle tells us that the Duke of Connaught, a relative of Kaiser Wilhelm II, drew his attention to the announcement of the regatta in Cork and the Duke asked for a German team to be sent to Ireland. The Emperor turned to Privy Councilor Georg Büxenstein with this request. Büxenstein, who was the owner of a printing company in Berlin, had regular access to the Emperor. Büxenstein was a rower and a sailor. As a young man, after a dispute over the sporting orientation of the Berliner Ruder-Verein von 1876, he had left it and founded the Berliner Ruder-Club with a few like-minded people.

He was also involved in establishing the German Rowing Federation, and he was a co-founder of the Berlin Regatta Club. He was elected chairman and through him competition rules were established. Then Büxenstein persuaded the Kaiser to allow the Regatta Club to lease several hectares of forest around the regatta course in Berlin-Grünau for 90 years so that rowing and sailing clubs could settle there. This made it possible for the Regatta Club to create the infrastructure with grandstands and boathouses for the regatta course that still exists today.

From 1904 to 1919, Büxenstein was chairman of the German Rowing Federation and in this role set the course for the development of the Federation.

As honorary chairman of the Berliner Ruder-Club, it was in his interest that his club should represent Germany in Cork. Though, it was agreed that a selection regatta should be held in Grünau to send the strongest and most promising crew to the start line in Ireland to show the strength of German rowing abroad.

At the regatta, racing in the coxed four for the famous Kaiserpreis, and a race where club crews would prove themselves worthy to represent Germany in the eight, the honour fell on the Berliner Ruder-Club after two victories, in the “Kaiser four” and in the eight. After that there was no question which club was going to be sent to Cork. The only concern was the length of the course, which at 3200 metres was much longer than the usual 2000 metres.

The cost of the expedition for the Germans did not play a role. It was known that the regatta organiser in Cork, the Hamburg-America Line of North German Lloyd and sports enthusiasts from the club would make financial contributions, so that the club’s coffers would not be burdened, and the cost for the club would not be more than for a local regatta.

On Friday 11 July 1902, the Berliner team of H. Miaskowski, F. Scheibert, E. Giese, F. A. Hemme, F. Hemme, Martin Spremberg, E. Miaskowski, Paul Gries, two substitutes (W. Pagels and Kunith), coach Willi Ullrich and the vice chairman Bruno Tummeley met up for their Ireland trip at Lehrter Bahnhof. Tummeley was greeted with great enthusiasm at the railway station. This was less due to him personally, but more to his well-filled travelling fund. The team spent the night in Hamburg, from where they travelled to Cuxhaven the next day and boarded the Blücher. The North Sea was a little choppy and not all members of the travelling party had sea legs.

They reached Southampton late via Calais, where they were expected at the hotel.

The menu of ‘Fish, ham and eggs, meat and jam, plus white bread and the dreadful beer’ dampened the excitement of the German team somewhat. Though, the reserved compartments on the train brightened the mood the next day. However, there was a brief scare before departure when one of the oarsmen was missing. The rower was roused from his sweet slumber in his bed and was put on the train in time.

Word of the Berlin travelling party spread quickly, and a delegation from the Waterford Boat Club was waiting for them at a railway station and invited to take part in a local regatta.

Arriving in Cork, they were greeted by the secretary of the regatta committee, Mr Doherty, and escorted to the Temperenz Hotel Metropole, which would provide board and lodging for the next ten days.

The first point on the crew’s programme was to visit the regatta course. Their eight had set off on its journey from Berlin on 27 June, well packed in a wooden crate and accompanied by the club’s boatman, Schatzki. Now the crew wanted to see for themselves how well it had survived the journey.

The Berliner oarsmen enjoyed being the centre of attention and proudly collected reports from the press. They explored the city and realised that a Berlin orchestra was playing at a garden exhibition. Though, however much they enjoyed their visit to Cork, they noted that ‘we didn’t want to get used to the English food and the word “chicken” quickly became a cry of horror.’

The regatta itself has already been well described in Greg Denieffe’s article. I can add that one rower in the Berliner boat had to be replaced (it is uncertain who this was but it was probably W. Pagels who took his place in the boat). However, it is unlikely to have had any influence on the outcome of the race against Leander.

The last evening in Cork was spent in the house of the merchant Harrington, whose wife spoke German and who entertained the Berlin team in a cordial manner. A trip to Queenstown and breakfast at the Royal Cork Yacht Club in honour of the crew concluded the official stay.

A telegram reached the Berliner oarsmen to inform them that the steamer for the return journey was three days late, so they took the opportunity to make another excursion of the surroundings of Cork. Finally, they said goodbye, survived the crossing over the rough Irish Sea and were once again on the train, this time bound for Southampton. From Reading, the railway company provided an extra train so that the ship could be reached on time.

Nonetheless, this proved to be unnecessary, as the steamer Barbarossa did not arrive until the next morning. The journey across the North Sea to Bremen, where they sat together for the last time in the Ratskeller, was uneventful.

Arriving in Berlin, a telegram from the Emperor surprised the Cork travellers. He congratulated them on their performance and appearance.

That was not the end of the story. On 26 September 1902, the High Sheriff of Cork, Mr Augustine Roche, arrived in Berlin. In his luggage was a cup of honour donated to the Berliner Ruder-Club by the people of Cork in memory of the competition. The club chronicles repeatedly emphasise that this cup of honour – from then on called the Cork Cup – was made according to the original cup won by Leander.*

On Friday 27 September, there was a banquet in the Hohenzollernsaal of the Hotel Kaiserhof with 180 members and guests. The Emperor was represented by Admiral von Tirpitz, who thanked Mr Roche and his friend Mr Dowling for their hospitality and reception in the city of Cork and expressed the Emperor’s gratitude.

Then Mr Roche gave a speech, and in response the representatives of the club thanked him and awarded him an honorary membership of the Berliner Ruder-Club. The banquet was accompanied by music, there was eager singing and it was noted that the cup of honour presented could be filled with 30 bottles of champagne. This was emptied in the course of the evening.

On Saturday, the guests attended a performance at the opera house. They saw Carmen in a box provided by a club member.

On Sunday, the club’s boatyard was festively decorated. The brass band, with whom contact had been made in Cork as they were also from Berlin, played Irish melodies in the boatyard. The eight named Preußen, which had survived the return journey, was christened Cork in honour of the guests. The Irish guests then travelled on a steamer through the club’s rowing area to Grünau. Here they visited the sports monument and had a bite to eat at the regatta course. Not only members of the Berliner Ruder-Club were present at the boat naming. Delegations from many clubs were represented, and on the steamer trip to Grünau, the party passed boathouses, which had been flagged and decorated in honour of the Irish guests. Members of the rowing clubs had lined up on the shore to form a guard of honour. This visit became a major event for rowing in Berlin.

After the Irish guests had travelled back to the city, a small group dined at Georg Büxenstein’s house in the evening.

The Cork Cup is still held in high regards at the Berliner Ruder-Club today. In Germany, the visit prompted people to wonder what would have happened if they had competed with other oarsmen, perhaps stronger rowers from different clubs in the same boat. Wouldn’t a regular comparison show how strong Germany’s rowers are? Why not compete regularly at the regatta in Henley and measure yourself against the best rowers?

As in other areas, the aim in rowing was to be as good as the English and, if possible, better. The coverage in the journal Wassersport shows that the Berlin team’s performance was very closely observed and discussed. The regatta in Cork was not mentioned in the magazine after the spring of 1903. Henley Royal Regatta had a much greater impact. However, the desire for regular comparisons with top foreign teams became so widespread that from then on German crews took part in foreign regattas more regularly and regatta organisers were encouraged to allow more foreign crews to compete in Germany.

Under Georg Büxenstein, the German Rowing Federation joined FISA in 1912 in order to enable clubs to compete in the European Championships. From then on, German rowing was no longer just an observer and occasional visitor to regattas abroad. The regatta in Cork was an important piece of the puzzle on the way there.

*Let me end this article with a fun fact: the cup of honour made for the Berliner Ruder-Club based on the original cup in Cork looks very different to the cup won by Leander Club in Cork. Nevertheless, we proudly present it in our trophy cabinet.

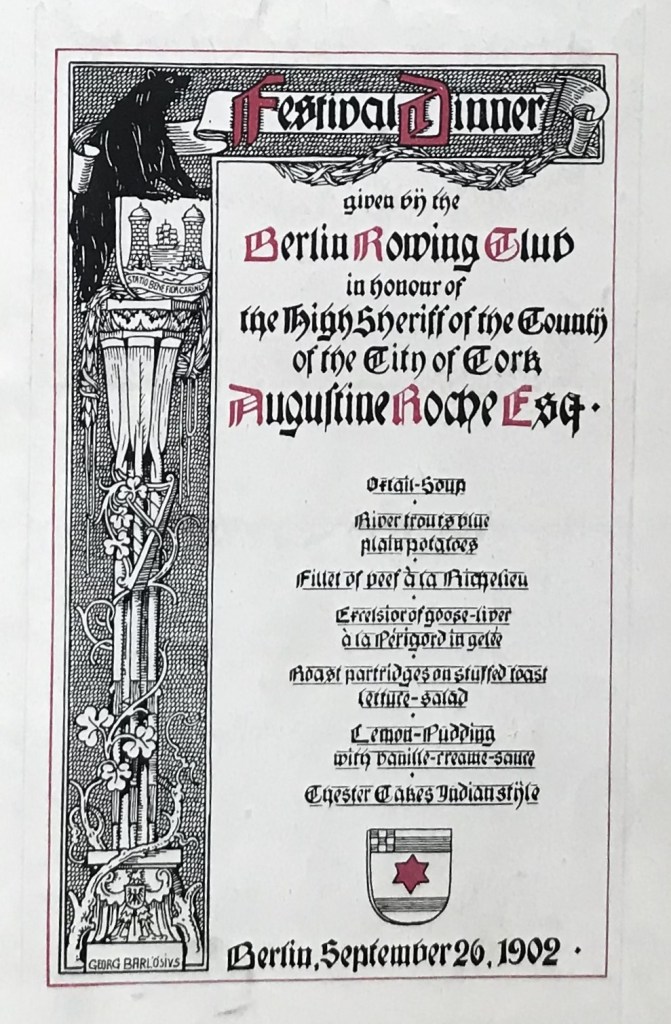

The menu at the Hotel Kaiserhof deserves a closer look, not just for the food but for the intricate decoration and beautiful lettering by the well known graphic artist Georg Barlösius. The motto “statio bene fida carinis” – “a safe harbour for ships” – is the motto of the city of Cork, and the bear with its front paws on the shield is a symbol of Berlin. The crew will have enjoyed the roast partridges on stuffed toast, lemon pudding with vanilla cream sauce, etc, more than the “Fish, ham and eggs, meat and jam plus white bread and dreadful beer” they had been subjected to in England.