“As he spoke Jove sent two eagles from the top of the mountain, and they flew on and on with the wind, sailing side by side in their own lordly flight.” – Homer, The Odyssey, Book II

9 June 2024

By William O’Chee

The 8th June marks one hundred years since George Mallory and Sandy Irvine disappeared just below the summit of Mount Everest. HTBS contributor William O’Chee explores the background to this expedition, and its curious mix of rowing and espionage. (Part I is here.)

Less than a week after the 1923 Boat Race, Irvine was learning to climb with Noel Odell and another member of the Spitsbergen expedition, Geoffrey Summers. Irvine and Odell spent most of the Spring climbing in North Wales, often in the company of Geoffrey Summers and his brother Dick.

Standing over six feet tall, with chiseled cheek bones and jawline, and a shock of blonde hair, Irvine was the very image of a Greek god who had come down on the Isis. He was never short of suitors of all types, although his tastes were decidedly and singularly heterosexual.

Whilst he was in North Wales, Irvine somewhat perversely became subject to the attentions of Geoffrey and Dick Summers’ 25-year-old stepmother, Marjory. These attentions rapidly became an infatuation, and Marjory Summers outraged everybody by her total indiscretion. She was oblivious of her husband, and was everywhere with Irvine in London and Henley, even travelling with the expedition as far as Tromsö! It was an infatuation which would eventually cost her her marriage.

It was during the course of the Spitsbergen expedition that Odell came to recognise not only Irvine’s superb stamina, but his extraordinary ability to deal with and fix a wide variety of technical equipment from compasses to oxygen apparatus.

What Irvine did not realise when he accepted the invitation to join the Spitsbergen expedition was that Odell was by then committed to the 1924 British expedition to Everest. While Irvine was learning the skills he would need for Spitsbergen, he was unwittingly auditioning for an expedition to Everest of which he initially had no knowledge.

The final say over the membership of the Everest expedition lay with the members of The Everest Committee, a joint venture formed in 1921 by the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club. The committee was the brainchild of Sir Francis Younghusband, the President of Royal Geographical Society, but also an old hand in the Great Game, the intelligence war with Russia in Central Asia.

Commissioned as a subaltern in the 1st King’s Dragoon Guards in 1882, Younghusband first became involved in the Great Game in 1886 when he was granted leave from his regiment in India to undertake an expedition from Beijing to Manchuria and the Changbai Mountains, surveying key passes along the way, and identifying possible Russian threats to China. In the following years he undertook expeditions across the Taklamakan, the Mustagh Pass, and through the Hindu Kush and the Parmirs. Much of this was at the direction of the Intelligence Department of the India Office.

During one of these missions, to Ladakh and the Yarkand Valley, Younghusband was escorted by a party of Gurkhas under the command of Charles Bruce. In 1923, when Younghusband was President of the Royal Geographical Society, the now Brigadier Charles Bruce became President of the Alpine Club. The two old comrades in the intelligence war were now in official control of the Everest Committee, although Younghusband had previously ensured Bruce’s appointment as team leader of the 1922 Everest Expedition.

None of this is surprising. British intelligence operations, whether conducted by what would become MI5 and MI6, or by the India Office, were thoroughly integrated with institutions like the Royal Geographical Society, Oxford and Cambridge universities, the British Army and the “right people” in British society. Summiting Everest was important in many ways, and Irvine was about to become part of this endeavour.

At Odell’s urging, Irvine was added to the 1924 expedition, principally to assist with the management of the oxygen equipment, which was still in its infancy. The climbing leader was 37-year-old George Mallory, who was a veteran climber, and a Cambridge graduate. Mallory was also a rower, having spent several years in the Magdalene College 1st VIII, although not as illustrious an oarsman as Irvine.

Most importantly, Mallory had been on the 1921 British Everest Reconnaissance Expedition, which explored the approaches to Everest, and the subsequent 1922 Everest Expedition that made three unsuccessful attempts on the summit.

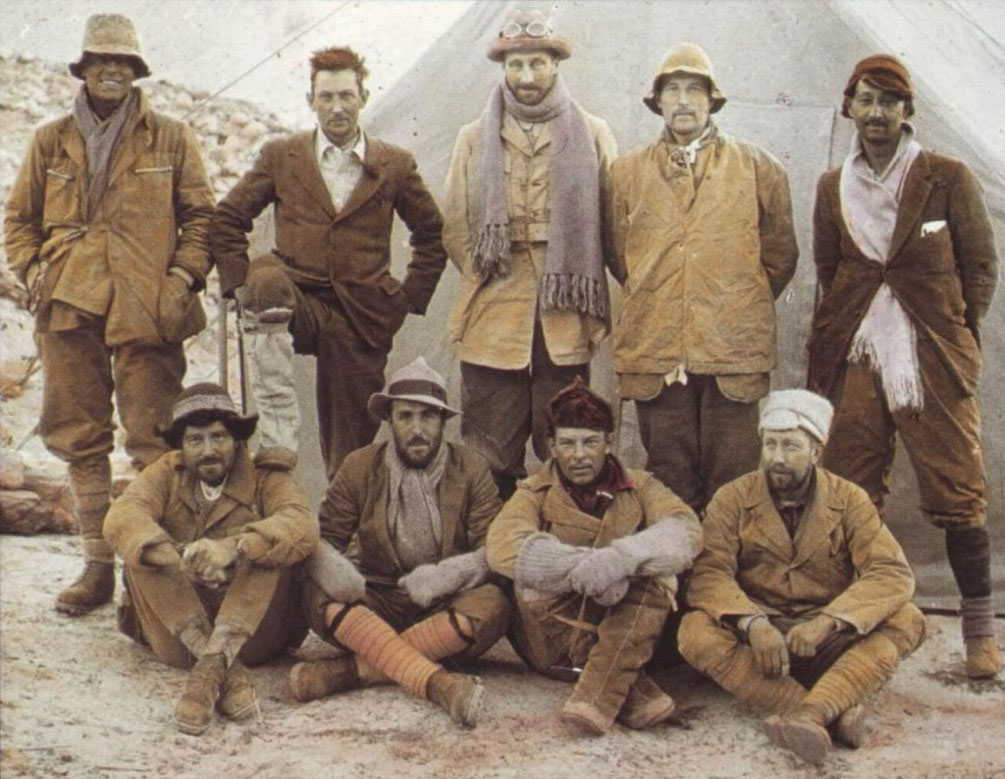

The team leader of the expedition was once again Charles Bruce. Other members of the 1924 expedition included Edward Norton, Geoffrey Bruce (a cousin of Charles Bruce) and Charles Somervell, who had all climbed with Mallory on Everest in 1922. Noel Odell was also on the team, as was John Noel, the team photographer.

Of the entire team, only Irvine and Edward Shebbeare had not fought in the First World War, although 40-year-old Shebbeare had been in the Imperial Forestry Service.

Unsullied by the war, Sandy Irvine represented a generational change in British mountaineering, and climbed without the ghosts which haunted the First World War men. Irvine’s youthful good looks only emphasised this difference more.

On the 29th February, 1924, Mallory and Irvine along with two other members of the team, Bentley Beetham and John de Vars Hazard, set sail for India on the R.M.S. California. During the voyage, Mallory and Irvine hit it off, and the young Oxford Blue greatly impressed his older Cambridge climbing leader.

After arriving in India, the team progressed to Darjeeling, where Irvine sought out Lady Lytton, the wife of Lord Lytton, the Viceroy of India. Lord and Lady Lytton’s son, Viscount Knebworth was a friend of Irvine’s at Magdalen College, and the pair had recently been skiing. As the team progressed through Sikkim, though, Brigadier Bruce fell ill with malaria and had to hand over leadership of the expedition to Edward Norton, who was his deputy.

After traveling through Tibet, the team planned to ascend the northern side of the mountain, since the other approaches to the summit lay within Nepal and were off limits. They left their base in Rongbuk on the 3rd May. From here they would establish progressively higher camps.

Unfortunately, bad weather disrupted this plan, and the mountain had to be temporarily abandoned due to a severe snowstorm.

It was not until the 17th May that upward process was resumed, although Irvine suffered diarrhea. Nonetheless, they were able to establish Camp IV on the 23rd May at height of 7,000m, only to be forced back down shortly after.

Only on the 1st June were Mallory and Geoffrey Bruce able to establish Camp V on the North Ridge at a height of 7,681m. However, many of the porters had now reached their limits, and their encampment was just “Two fragile little tentlets perched on an almost precarious slope” as Norton was to write. Things were well behind schedule, and the weather was poor. This summit attempt had ground to a halt. Mallory’s plan was falling apart.

The following day Norton and Somervell launched another attempt at the summit, climbing the retainer of the North Ridge for 200m before trying to traverse diagonally across the North Face. Going was hard and Somervell had to stop. Norton pushed on, picking his way over loose rock in a gully known as the Great Couloir (later Norton’s Couloir) but without oxygen he had managed to climb only about 80 feet in the space of an hour. As the going got more difficult, the unroped Norton finally turned back at 8,572m, a world record. However, Norton was left with snow blindness, and Somervell almost died of the effects of the altitude as he came down.

There was a pause to get medical aid to the men before a third attempt on the summit was launched by Mallory and Irvine from Camp IV on the 6th June. Odell photographed them fiddling with the oxygen apparatus before leaving. It was the last photo taken of the pair.

With Mallory and Irvine were eight sherpas, who carried provisions. Camp V was reached, from which four porters were sent back. The others pressed on to Camp VI. Following behind this party was Odell, who stayed with a sole sherpa at Camp V as a support.

Mallory sent the remaining sherpas down with two notes. One was for Odell to say they had 90 atmospheres of oxygen for two days and would probably take two cylinders, but that the weather looked fine. The other note was for John Noel, who was filming from Camp III to say they intended to set off on the morning of the 8th, and that he should look for them either on the rockband below the pyramid, or else going up the skyline at 8 in the morning. Odell planned to move up from Camp V to Camp VI at the same time to support them if needed.

The morning of the 8th June did not begin with clear weather, however. When Odell left Camp V at 8 o’clock there were bands of mist and light snow sweeping across the mountains from the west. At 12:50pm his diary records he saw the pair “nearing the base of the final pyramide”. Later he would expand on this and write:

“…there was a sudden clearing of the atmosphere, and the entire summit ridge and final peak of Everest were unveiled. My eyes became fixed on one tiny black spot silhouetted on a small snowcrest beneath a rock-step in the ridge, and the black spot moved. Another black spot became apparent and moved up the snow to join the other on the crest. The first then approached the great rock-step and shortly emerged at the top; the second did likewise. Then the whole fascinating vision vanished, enveloped in cloud once more.”

Odell saw them no more. A snow storm closed in which forced him back to Camp VI. At 4:30pm he abandoned the camp as there would not be room for three in the tent there, so he moved down to Camp IV, which he reached by 6:45pm.

With no sign of the men that night, Odell set off with two sherpas the next day to go to Camp V. They stayed there that night, before Odell went alone to Camp VI which was deserted. He laid out sleeping bags to form a T to signal no hope of their having survived, then made his way back down alone.

That was all that would be known of the men. In 1933, Percy Wyn Harris found an ice axe, now believed to be Irvine’s, to the west of the first step. In 1999, an expedition organised by Eric Simonson found Mallory’s body several hundred feet below this ice axe. He had been roped, but the rope was broken. One of Mallory’s legs was broken and he had a hole in his skull. Irvine’s body has not been found.

That would be all, but the ghosts of Everest bid us know no certainty. Mallory had taken a photo of his wife with him, which he intended to plant on the summit. It was not on his body. Did he leave it on the summit?

Irvine had a camera, which, if found, could contain film that would prove that they made it to the summit or not. However, like Irvine himself, the camera has not been found.

Opinions amongst mountaineers are divided on whether the pair reached the summit. The position of Mallory’s body, well below where Odell believed he saw him, suggests the pair were descending when there was a fatal fall.

Wade Davis, who is largely acknowledged as the foremost expert on the subject, believes the pair made it to the bottom of the second step, but were prevented from climbing higher by the vertical wall of rock, and their rudimentary equipment. Others, such as Mark Horrell, believe they may have made it past the second step, in which case the summit would have been in reach.

Whatever happened that afternoon, Mallory and Irvine probably climbed higher than any human being before them. So close did they come to the Nepalese goddess of the sky, Sagarmatha, that they passed into legend like gods. They became like Jove’s eagles, braced forever by the winds that swirl across the face of the mountain.

Yes, that is how I shall remember them.

A wonderful account of shear bravery & an unsolvable question. Thanks, John Beresford.

In 1951 I sat in the seven seat of the University of Pennsylvania 150# crew that was the first to win at Henley. Our final in the Thames Cup was against a 183# German crew and a strong head wind. We came from behind to win. Returning to the dock two were helped out and I was carried out. We were staying at the home of Doctor K Neville Irvine, former Oxford Blue, prominent pediatrician and brother of Sandy. Upon returning to his home he examined me and said “Well Dick, you are going to be all right but I want you to remember that rowing and mountain climbing are benign forms of insanity”. I am 94, still rowing my single and enjoying it.

love your comment

What a wonderful article – many thanks! I always like to hope that they made it to the top, but we’ll probably never know. It was a heroic and tragic attempt; long may they be remembered.