6 June 2024

By Tim Koch

Tim Koch remembers many by remembering one.

Today, 6 June 2024, is the 80th Anniversary of D-Day, the first day of the Allied forces combined naval, air and land assault on Nazi-occupied France. The Germans had been deceived into expecting a landing at Pas de Calais but in reality, the Allies had targeted a 50-mile stretch of Normandy coastline.

The first day of the invasion was conducted in two main phases, an airborne assault followed by amphibious landings. Shortly after midnight on 6 June, over 18,000 Allied paratroopers were dropped into the invasion area to provide tactical support for infantry divisions on the beaches. Starting at 6.30am, more than 150,000 ground troops landed across five beaches on the coast of Normandy. By the end of the day, American, British and Canadian soldiers had established a foothold along the coast and could begin their advance into France and ultimately into Germany itself (though it is often overlooked that the war in Italy and the Far East also had to be won).

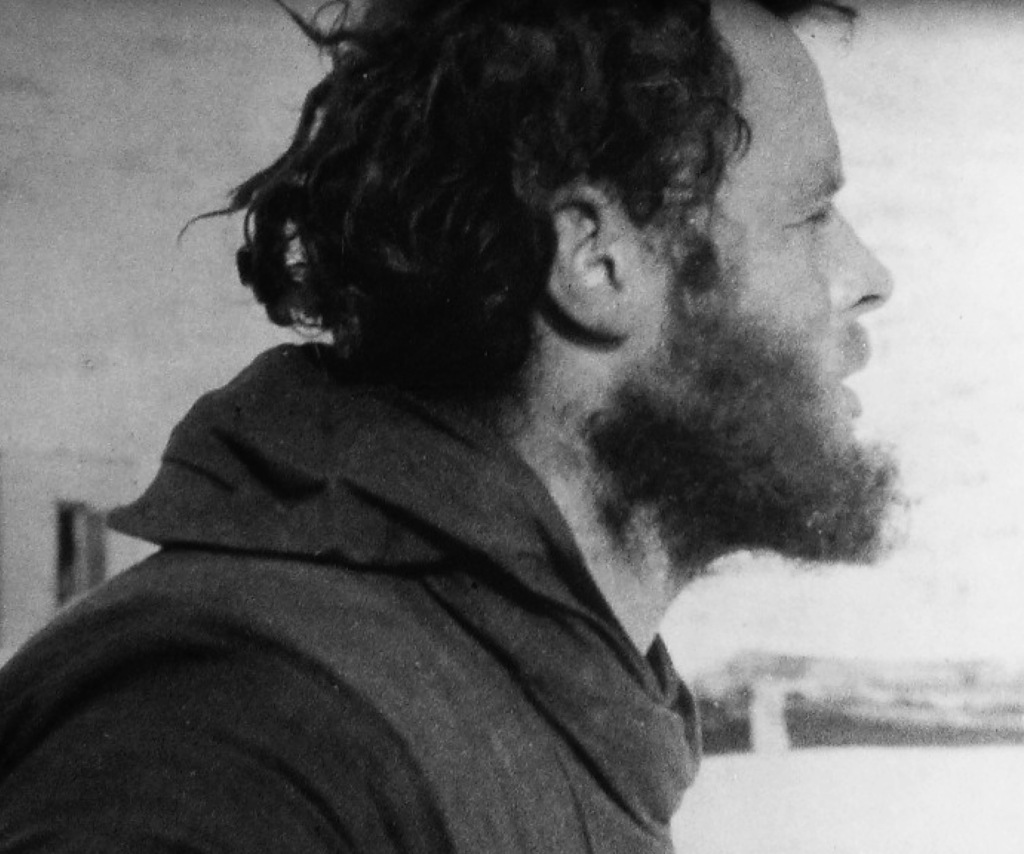

Among those 18,000 paratroopers who were the first to begin the liberation of Nazi-occupied Europe was 120492 Lieutenant David Haig-Thomas (DHT) of the Royal Army Service Corps and No. 4 Commando. Within a short time of landing he was killed in action, one of nearly four-and-a-half-thousand Allied troops to die on D-Day itself.

The Father’s Son

Like his father, David Haig-Thomas’ life was dominated by rowing, wildlife and adventure. But, unlike his father, DHT was also a remarkable soldier.

DHT was the second son of Peter Haig-Thomas (PHT). Four years ago, I wrote a four-part biography of the father (Peter Haig Thomas: The Unorthodox Orthodoxist), a unique character who spent sixty years as an active and influential figure in rowing but whose long-term fame has been overshadowed by the apparent greater coaching success of his great rival and near-contemporary, Steve Fairbairn. It began:

Anyone looking at British amateur rowing in the period between the death of Queen Victoria and the birth of the Space Age will, at regular intervals, come across the name of Peter Haig Thomas, (1882 – 1959). I have long had a vague awareness about the man: he had a short, successful rowing career and a long, successful coaching career; he was a fanatical advocate of the “Orthodox” style of rowing; he lived the life of a Victorian gentleman adventurer long into the 20th century; he had a colourful private life.

In a brief aquatic career starting at Eton in 1896 and finishing at Cambridge in 1905, Peter Haig-Thomas won most things worth winning when rowing at school, university or Henley. After that, he spent the next fifty years coaching virtually whoever asked – providing that his unyielding and virtually unchanging ideas on how to produce boat speed were not questioned. In 1920, he inherited £2m but, through a life wholly dedicated to rowing, field sports and women coupled with a very poor business sense, he managed to reduce this to £150 by the time of his death in 1959.

Also in Part I of PHT’s biography, I wrote:

Peter Haig Thomas may have been keen with a gun, but he did not take part in the two biggest shoots of all. He spent the First World War managing coal mines in Wales and the Second World War in the Home Guard on his Scottish Estate. We can only speculate why he did not follow the vast majority of his contemporaries of the “officer class” and enlist in the military during the Great War. He would have been 32 in 1914, a perfectly acceptable age for a commission…

However, his son had no such scruples about military service.

PHT’s first wife and David’s mother was Maud Nelson, the sister of a fellow oarsman from Eton and Cambridge, Roland “Rowley” Nelson. They had three children, Anthony, born on 12 January 1908; David, born eleven months later on 1 December 1908; and Enid, born on 2 June 1911. Maud died in 1913 giving birth to a fourth child who was stillborn.

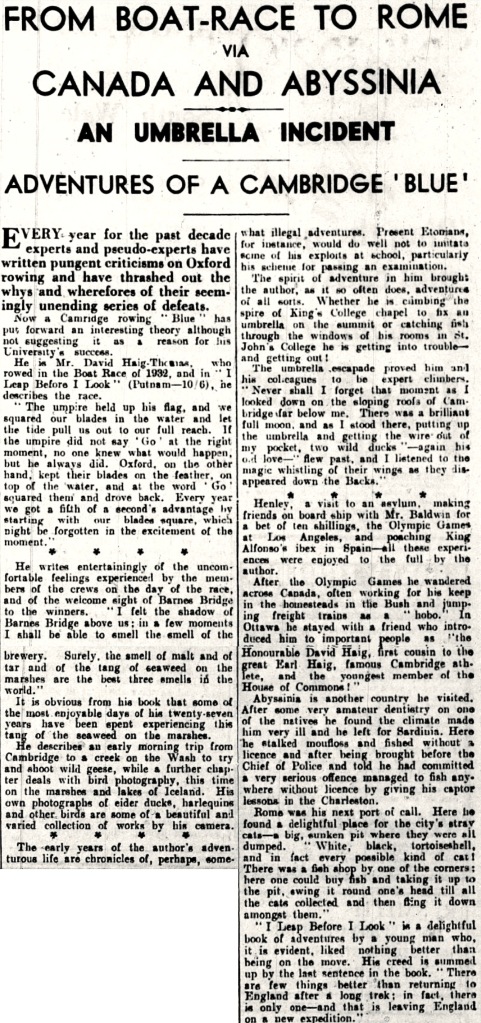

Snapshots of DHT’s personality, a wild character who had periods of thoughtfulness, can be had from reviews of his autobiography, I Leap Before I Look, published in 1936 when he was just 28:

The Spectator, 5 February 1937:

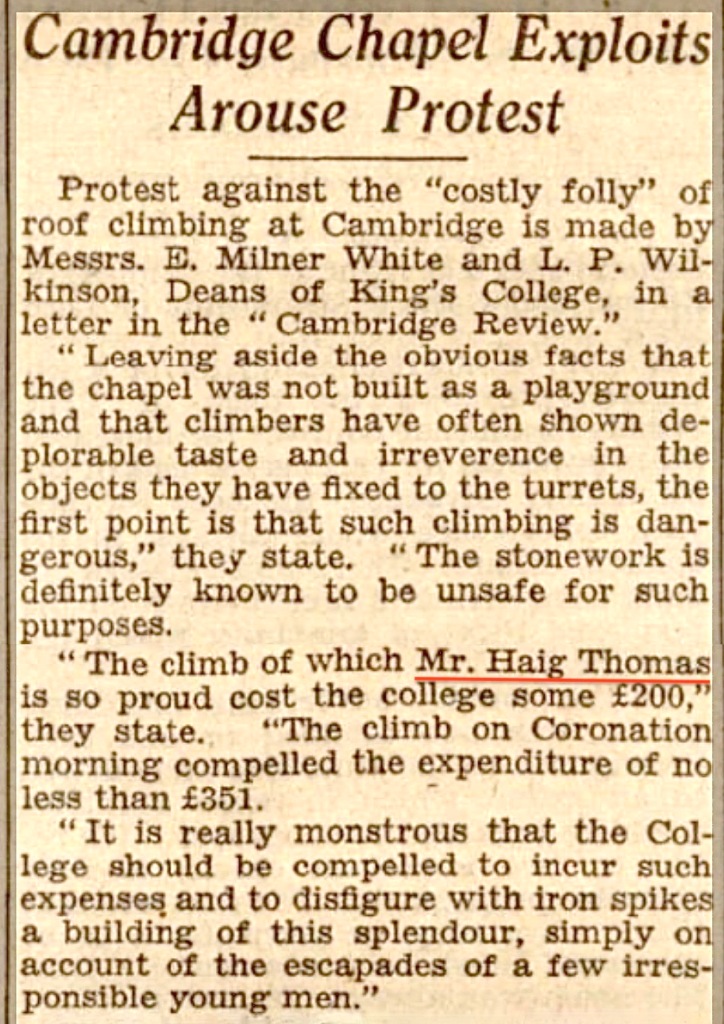

Undergraduates are commonly divided into intellectuals and toughs. The latter are supposed to be inarticulate. But though Mr. Haig-Thomas no doubt handles an oar or a gun with more assurance than a pen, I Leap Before I Look demonstrates once more that these implements are not mutually exclusive. He has written a straightforward account of the more exciting moments of his youth, mostly passed in the pursuit of thrills. He found them in raiding the printers at Eton for examination papers, tying umbrellas to the spires of King’s College chapel, rowing in the University boat-race, poaching ibex in the Pyrenees and photographing wild geese on the Fens—his favourite occupation. Being in America for the Olympic games, he decided to visit friends in Canada, and having no money made the journey by “jumping” a freight train, and then kept himself by odd jobs on farms. All this is amusingly described. But it is his passion for the solitude of the marshes and the call of flighting geese that leavens the toughness of his outlook and distinguishes his book from the usual records of thrill-hunters.

Eton

I can find very little information on DHT’s career at Eton, but I imagine it mirrored his later time at Cambridge: rowing, pranks and minimal academic work. I think that he may have been overshadowed at school by Anthony, his brother older by eleven months.

The Times of 5 June 1924 lists Anthony Haig-Thomas, “The son of the Old Cambridge Blue,” as stroke of Eton’s Henley crew. He weighed just 60kgs and was, prestigiously, Eton’s Captain of Boats and stroke of the First Eight. Perhaps with a little hyperbole, The Eton Book of the River (1935) described him as “perhaps the best stroke and oar combined yet seen in the school.” He died following an operation aged just 16 in September 1924.

Cambridge

Perhaps up until the Second World War, for some, gaining admittance to Oxford or Cambridge may have relied more on coming from “a good school” or “a good family” rather than showing intellectual promise. Both universities gave what was in effect an attendance certificate to its dullest graduates in the form of a Third from Cambridge and a Fourth from Oxford. Famously, these were known as “Oarsmen’s” or “Gentlemen’s” Degrees. Some did not achieve even these. In his autobiography, DHT, a third generation Cantab and a second generation rowing Blue, wrote:

I, like my father and my grandfather before me, would go down without a degree. Grandfather never looked like passing an exam. Father passed one and I had passed two, and I thought it would spoil the family tradition if I did any more, as well as impertinence on my elders and betters!

Like DHT, some of those who got poor or even no degrees were not intellectually incapable, they simply found the social and athletic life of university more important than the academic. As his later career would show, DHT was not lacking in intellect.

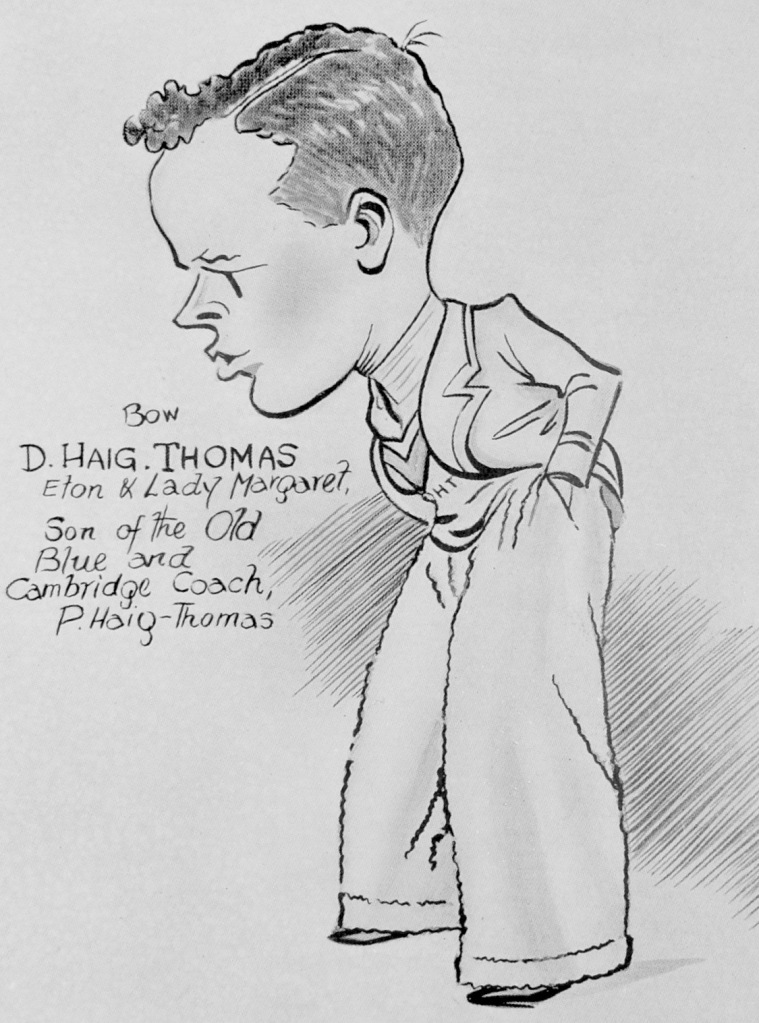

DHT was at St John’s, an ancient and wealthy Cambridge college whose boat club is called Lady Margaret. He was in the Lady Margaret crew that won the Ladies’ Plate at Henley in 1930. There were twenty entries and in the final, Lady Margaret beat Pembroke College, Cambridge, by a length. Rowing in his usual bow seat, DHT weighed in at 11 stone 3 pounds (71kgs).

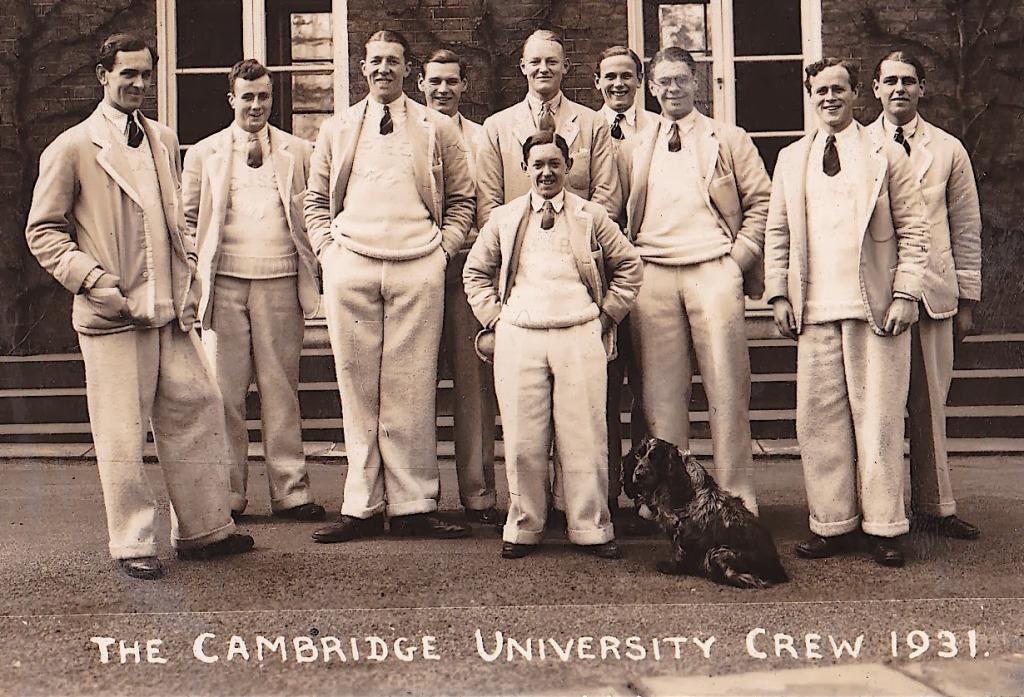

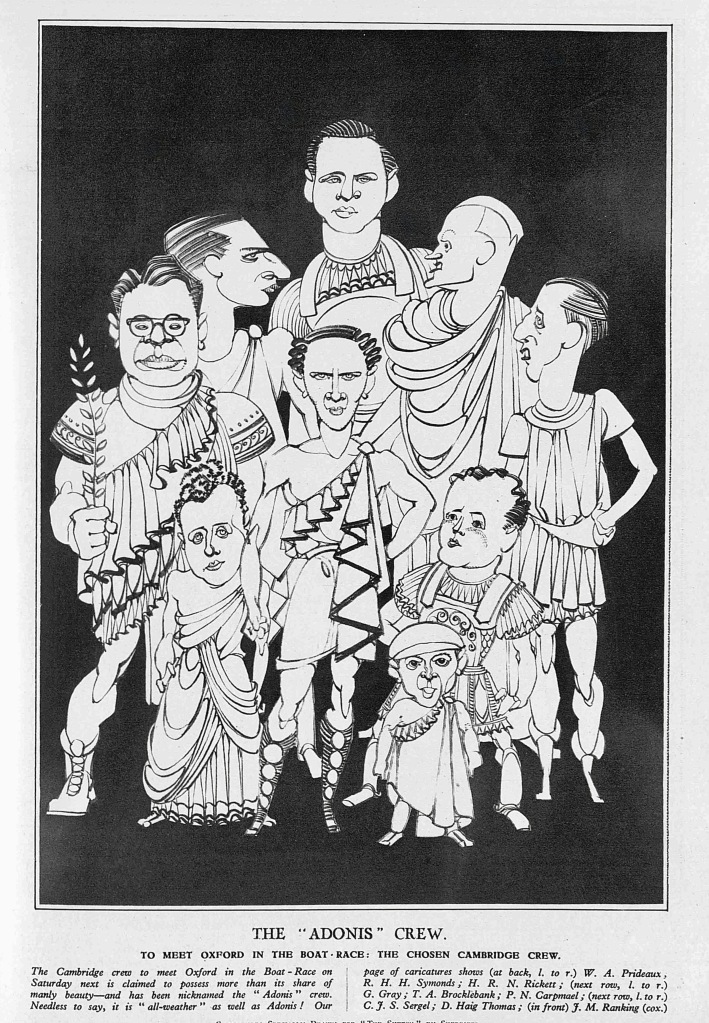

Cambridge won every Boat Race between 1924 and 1936 and DHT was bow in the winning Light Blue crews of 1930, 1931 and 1932.

During the trials for DHT’s first Boat Race, that of 1930, The Times of 2 December 1929 said of him:

Haig Thomas… created a good impression (at the December Trials). It is by no means unusual for a comparatively weak man to become a really good oarsman, and Haig Thomas’s timing is so good that he is more effective than many men endowed with much more weight and strength…. (His) style of rowing gives one confidence that he would not falter even in a close race, and although he has a high standard of style to live up to as his father’s son, he was not found wanting in that respect.

In his last Boat Race (1932), The Times held that, Haig Thomas is better than he has ever been, longer with his swing and firmer with his finish.

1932: A Good Year

The same Cambridge Crew that won the 1932 Boat Race in March also won the Grand at Henley in July (rowing as Leander) and came fourth in the Eights at the Los Angeles Olympics in August (rowing as Great Britain). DHT was in the bow for all three of these events.

At the Olympic Regatta in Long Beach, California, the British eight came second in the first round, four-seconds behind Italy. They won the repechage, three-seconds ahead of New Zealand. In the four boat final, they were last but were only 0.4 seconds behind third placed Canada and three-seconds behind the winners, the USA. In his autobiography DHT claims that an Olympic official told his crew that, had they won, they would have been disqualified for swearing. He took solace in this.

Marriage

In 1936, DHT married a debutante, Nancy Bury, and they had two sons, Tony (1937) and David (1940). Like his father and many other men of his generation and class, marriage did not mean that he had to stay at home or cease having lengthy global adventures. The newspapers reported that, “The honeymoon will be spent in Iceland where the newly married couple will enjoy salmon fishing.” I speculate that the enjoyment of angling in sub-zero temperatures was one-sided.

Ornithology and Exploration

In the Daily Telegraph of 24 January 2015, Sarah Wheeler wrote:

David Haig-Thomas was one of a group of Britons who came to embody the marriage of intellect and action that characterised exploration in the 1920s and 30s. The jingoistic British public were gasping for heroes, especially since ideals had perished by the million in the First World War. Explorers were knights errant who enabled national self-belief. The period marked a golden era between the drama of the Heroic Age and the transformative technological leaps that followed. Mallory, Tilman, Shipton – all exemplified the romantic metaphor of travel as a personal quest, a pure and idealistic pursuit that transcended war and economic depression.

One of DHT’s earliest expeditions was in 1933 when he joined his fellow Old Etonian Wilfred Thesiger on an expedition to trace the route of the Awash River in Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Sarah Wheeler:

The hawk-like Thesiger noted later that Haig-Thomas never brushed his teeth, took a bath or read a book, and he said he was glad to see him go when Haig-Thomas left the expedition because of illness (but Thesiger never liked anybody except his mother and African boys).

The Scott Polar Research Institute website summarises the rest of DHT’s expeditionary career thus:

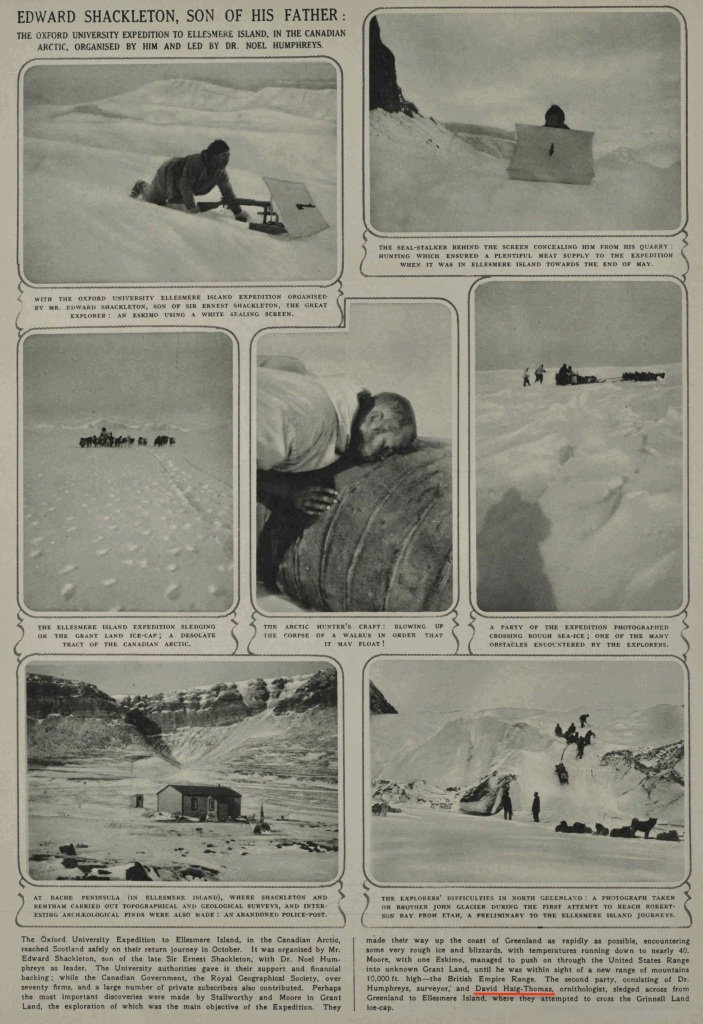

He was ornithologist on the Oxford University Ellesmere Land Expedition in 1934-1935. The main purpose of this expedition was to explore northern Ellesmere Island (Canada’s northernmost island, one only slightly smaller than Great Britain) and to map its coastline. He overwintered in Greenland in 1934-1935 and in spring 1935 sledged across Smith Sound and Ellesmere Island.

In 1936, he was leader of an ornithological expedition to Iceland.

In 1937-1938, Haig-Thomas spent a year in northwest Greenland and Ellesmere Island as leader of the British Arctic Expedition. The expedition arrived… in northwest Greenland in August 1937. He left… in March 1938, crossed Ellesmere Island and sledged to Amund Ringnes Island, Alex Heiberg Island, and (what became) Haig-Thomas Island in the Canadian Arctic. He returned to Greenland (where he) spent the summer of 1938…

Those in the UK can view remarkable film of the 1937–1938 British Arctic Expedition in northwest Greenland and Ellesmere Island on the British Film Institute site.

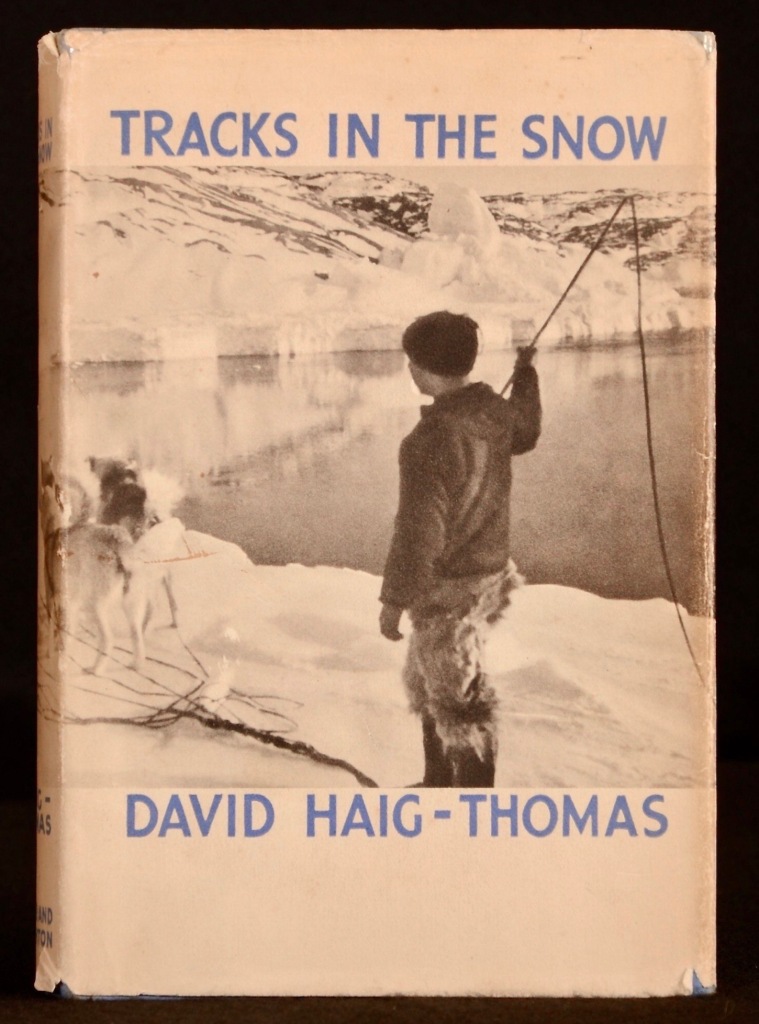

DHT was adept at self-publicity. He lectured and wrote about his adventures and published two popular books, his 1936 autobiography, I Leap Before I Look, and Tracks in the Snow, recalling his 1938 trek across Ellesmere Island. In the late 1930s, he commented on training for the Boat Race and wrote race day reports for the newspapers.

When Tracks in the Snow was re-published in 2015 to support the work of a new “Haig-Thomas Expedition” the publicity reflected DHT’s image of himself:

In 1938, David Haig-Thomas completed an extraordinary journey of over 1500 miles across the Arctic, using only the clothing, tools and equipment that he had picked up in his time there. This book tells the amazing story of how he lived amongst the communities of Northwest Greenland where he developed a deep respect for the people of the area and their unparalleled ability to thrive in this challenging environment. In doing so he provides a charismatic and unique insight into Inuit culture, hunting techniques and travel in the 1930s.

However, some have questioned the reliability of DHT’s works and of the accomplishments of his expeditions in general.

A minor example of DHT’s lack of rigour in his writing is noted in a history of his old college, St John’s, by Peter Linehan which calls I Leap “a volume of reminiscences notable for its tourist’s knowledge of College matters, eg the old canard that swan was served at the May Ball…” DHT was not a man to let the truth get in the way of a good story, particularly when he was the hero of any such tale.

DHT was criticised by William Barr in his 2023 biography of a long-serving Royal Canadian Mounted Policeman, Harry Stallworthy, titled Red Serge and Polar Bear Pants. In 1938, Harry Stallworthy was asked to comment on a proposal by DHT to mount a second expedition to Ellesmere Island. He criticised Haig-Thomas’ general attitude towards “any authority restricting his hunting activities” and wrote:

I know Mr Haig-Thomas intimately through our association on the 1934-35 Oxford University Ellesmere Land Expedition… I doubt very much whether his objective on the proposed expedition is entirely in the interests of science. His chief interest on the last expedition was undoubtedly big game hunting, which hobby he has pursued in other parts of the world. In this connection, I would suggest reference be made to my general report covering the Oxford Ellesmere Land Expedition, in which it will be noted that a number of walrus were slaughtered and sunk in a manner contrary to North Greenland Game Laws… and as a result two members of the expedition were charged with this infraction… Dr Humphreys and Mr Haig-Thomas…

DHT defended himself by claiming that walruses were shot for emergency food but there was no evidence for this. According to an Inuit guide, his illegal shooting of walrus was allegedly repeated on the 1938 expedition and that polar bears and caribou were also hunted. The guide further complained that DHT rode on the sled for the entire trip even when this made steering it difficult.

Of course, modern attitudes to hunting should not be imposed on ages past but the motives of Europeans abroad in lands strange to them are of legitimate interest.

Lyle Dick is an “Arctic historian” and President of Canadian Historian Association. In his Muskox Land: Ellesmere Island in the Age of Contact (University of Calgary Press, 2001) he notes:

Following its establishment in 1928, the Oxford University Exploration Club, like its counterpart at Cambridge, sponsored a large number of expeditions in the 1930s. The emphasis was on polar exploration in both the Arctic and Antarctic regions. The Oxford Club was essentially an undergraduate organisation, but more senior and experienced members were customarily included to install discipline and encourage the publication of findings.

Dick’s writings give a left/liberal/academic perspective, the antithesis of that portrayed in Tracks in the Snow. He is of the view that the Oxford University expeditions to Ellesmere Island in the 1930s:

… were of minor importance to Arctic science (but) they illustrated something of the character of romantic adventure seeking during the twilight of the British Empire… Upper-class traditions of grooming the younger generation and inculcating responsibility through physical challenges… were well entrenched from the heyday of “Muscular Christianity…” The specific goal of an expedition was not so important as its role in building character and training future members of Britain’s ruling class… More general motivations are suggested by the Oxford party’s depiction of Ellesmere Island as “the most northerly part of the British Empire.” The expeditions helped maintain an illusion of Anglo-Saxon pre-eminence around the globe in a period of Britain’s rapidly declining influence.

Lyle Dick concludes that by 1939 DHT had accomplished little for Arctic science (but) had acquired enough anecdotal material to build a reputation among Arctic enthusiasts. He claims that the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) unquestionably backed DHT over the walrus shooting and that the RGS also criticised the Canadian Government for ever doubting him. The Scott Polar Research Institute at Cambridge has a more sober online account of the 1934-35 expedition plus 150 photographs.

While DHT clearly loved birds, this did not stop him shooting them for sport for at least part of his life. This is a paradox to modern minds but the great ornithologist, Sir Peter Scott, wrote in his autobiography, The Eye of the Wind (1961):

After many years of wildfowling, the first inklings of (a) changing attitude came to me on a marsh where, one early spring day in 1932, David Haig Thomas and I had shot twenty-three Greylag geese. Among them were two wounded ones, and as soon as we had picked them up we hoped that they might not die.

Whether the university expeditions of the 1930s were wizard wheezes by overconfident undergraduates or were serious and useful academic studies,by the late 1930s most people had their minds on political matters in Europe. By September 1939 the continent was at war and DHT’s very specific skills were in great demand.

Commando

DHT had joined the Reserve of Officers before the war and on 2 March 1940 he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC) serving in Iceland and Greenland. The RASC was responsible for logistics, a necessary but unglamorous task. He was later to call the three years that he spent with it “wasted” but at the end of 1942 he joined a unit more suited to his skills and character, the Commandos.

The Commandos had been formed in June 1940 following a demand from Winston Churchill for special forces that could carry out raids in German occupied Europe. By 1945, 25,000 men had passed through Commando training at Achnacarry.

Technically commando soldiers were only on secondment, they retained their regimental cap badges and remained on the regimental roll for pay. If they did not meet the required standards, they were “RTU” (Returned To Unit).

After training, DHT joined No. 14 (Arctic) Commando, a unit that specialised in infiltration of enemy positions using kayaks. It was composed of those experienced in the use of such craft, including Canadians, Scandinavians and polar explorers such as Captain Scott’s son, Peter, and DHT himself.

In February 1943, DHT was posted to the Commando Depot, Achnacarry, Inverness-shire, Scotland, for attachment to No. 4 Commando. By 1944, he was a lieutenant in No. 4 Commando’s C Troop which specialised in climbing and parachuting.

For some time, DHT was under the command of Simon Frazer, the 15th Lord Lovat and the 24th Chief of the Clan Fraser of Lovat (1911-1995), who was instrumental in organising the Commandos and who was one of the few people who could make DHT seem shy, retiring and unadventurous.

Such was the effect that raids by Lovet’s commandos had on German morale, he allegedly had 100,000 Reichsmarks placed on his head for capture dead or alive. Famously, when his men landed under fire on D-Day, he instructed his personal bagpiper to pipe them ashore.

DHT was affectionately recalled by Lovat in his book, March Past! The Memoir of a Commando Leader, From Lofoten to Dieppe and D-Day (1978):

The man I remember best and not strictly a soldier was David Haig-Thomas… a more attractive and original volunteer never attempted to put equipment on; and David’s was usually upside down. He had the supreme gift of making soldiering fun. His enthusiasm was of an infectious kind that turned aside the rockets freely given for various misdemeanours…

His versatility was remarkable and for that reason I steered him clear of the more blunting kind of military routine. But whether he was rolling a kayak on a Scottish loch, demonstrating the construction of ah igloo on snow-fields in the Cairngorms, treating his section to samples of edible seaweed and raw shellfish off the Cornish coast, or simple giving a lecture on bee-keeping or butterflies to his men, David was in a class by himself…

Lovat again:

(On D-Day) the overall plan required the Commando Brigade to join with an Airborne Division dropped overnight… A man of proven ability was required to liaise in what might become a mix-up between red and green berets… David was the first man to volunteer. He asked for one favour: to take (Sammy) Ryder, his servant, with him…

(On the night of 5th/6th June) there was cloud over the moon; the (parachutists) were blown off course by wind, and badly scattered. Many fell on the wrong side of the flooded valley of the River Dives; some were lost, killed or captured, others drowned in their harness; a very nasty start…

The online Commando Veterans Archive has a communication between John Martin, nephew of Sgt Donald Martin, DHT’s section sergeant in C Troop, and Alex, DHT’s grandson:

I understand that his (group of parachutists) came down on marshy ground close to the River Dives and well away from where they should have landed. They were ambushed near a crossroads and (DHT) was killed…

My late uncle, Donald Martin, knew (DHT) well… He was very fond of your grandfather as I suspect were most of that section… I am sure that (he) was viewed as something of an oddity by his section, given his success as a pre-war explorer and naturalist and also possibly his age, though he had skills as such that were so valuable to No. 4 Commando (C Troop was a climbing and parachuting troop). I sense there was generally enormous affection for him…

As you probably know, most of our fallen are buried in (military) cemeteries but your grandfather, for some reason, was buried in Bavent churchyard where his grave always appeared so well tended.

His body was recovered by two young French boys who carried it to a farmhouse just outside the village. I met one of them in Bavent on a visit with my uncle and Sammy Ryder… He had found your grandfather’s service watch and kept it. During a very emotional moment, he gave it to Sammy. I felt that Sammy deserved that. He was a small pugnacious Scouser who had clearly worshipped your grandfather…

The diary of my father, Wally Milne, who was also an oarsman (Selwyn College stroke and briefly Boat Captain before being called up in 1939) and a keen amateur ornithologist, records that Haig-Thomas was one of his instructors at the School of Winter Warfare outside Akureyri in Iceland in March 1942. He mentions Haig-Thomas giving an evening lecture on Greenland and being with them up in the mountains on the Vindheimajökull (glacier) instructing them on how to build an igloo.