5 June 2024

By Greg Denieffe

Greg Denieffe finds that John Lavery, a painter from Belfast who ran with the hares and hunted with the hounds, occasionally found his way down to the river.

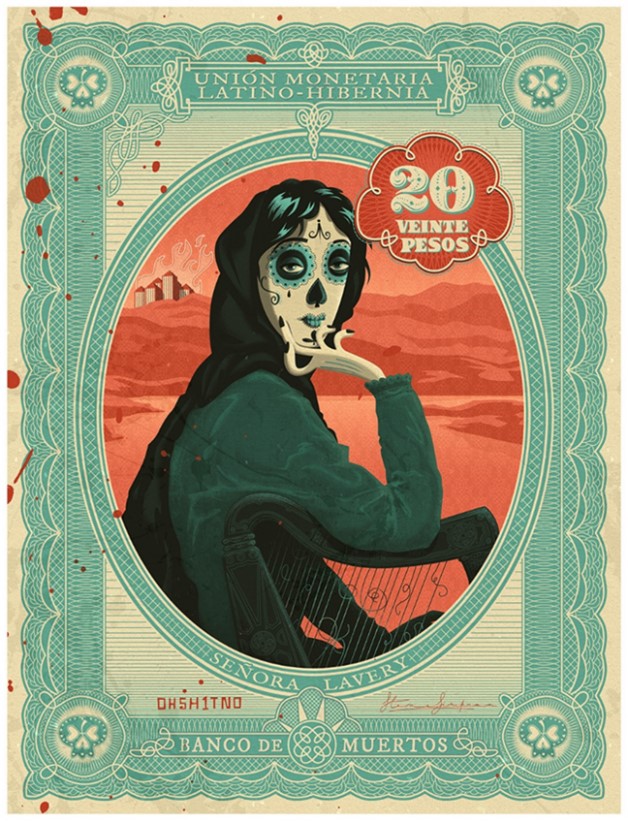

John Lavery (1856-1941) was an artist who came to the attention of people my age and older through the handling of spondoolicks in their various shades of orange, green, brown, blue, red, mauve, and olive. The Lavery Series of Irish Banknotes (1928-1977) ranged from 10 shillings to 100 pounds and carried a portrait of Lavery’s second wife, Hazel. The banknote image was based on Lavery’s painting, Portrait of Lady Lavery as Kathleen Ni Houlihan (1927). Despite breaking every requirement laid down by the Irish Currency Commission, Lady Lavery (her husband was knighted in 1918), an American with links to the British aristocracy, became the face of Ireland. Read how this came about on the website of auction house Spink & Son.

Lavery was born in Belfast and moved to Scotland when he was still a child. In 1878, he set up his own studio, which was destroyed in a fire the following year. With the £300 insurance payout, he spent a year studying in London before completing his studies at the Académie Julian in Paris. He found Paris expensive, and to save money, he spent time in Grez-sur-Loing, a picturesque village a few miles south of Fontainebleau, where he painted his first rowing scene.

In December 1998, Christie’s in London auctioned The Bridge at Grez, where it realised a hammer price of £1.3 million. According to their catalogue, what was remarkable about the painting was the evocation of summer indolence, the sense of space and dappled light, and the masterly handling of reflections in water – those ‘mirrored and inverted images of trees’ that Robert Louis Stevenson had noted as so typical of the river at Grez. Well, if that’s what the expert thinks, who am I to disagree? To my eye, it looks like a little flirting is going on between Monsieur Skiff and Mademoiselle Parasol.

By 1888, Lavery was back in London, working from a studio in Cromwell Place in the fashionable West End. In his lengthy career, he painted everyone from royalty and politicians to the clergy; certain sports held a fascination for him, like chess, tennis, and especially horse racing. Eventually, he discovered the sport of rowing. He relied on his huge output of work as a portrait painter for his livelihood and to finance his informal work, including dozens of paintings of the second Mrs. Lavery (m. 1909).

Lavery painted many riverside scenes, some with pleasure boats and some with punting, like the one above that also includes a coxed single sculling crew, perhaps a memory of his days in France.

During the First World War, Lavery worked unofficially for the British Government as a war artist, but owing to doctor’s orders, his plans to go to France were thwarted, so he stayed in London, painting the returning wounded, the war cabinet, airfields, and what the Imperial War Museum described as the war From Shore to Sea. For his war service, Lavery received a knighthood in the 1918 New Year Honours.

The political scene in Ireland changed during the war following the Easter Rising of 1916, leading to the guerrilla War of Independence (1919-1921). A truce was called in July 1921, and negotiations began immediately, but it wasn’t until October 1921, when an Irish delegation went to London, that any real progress was made. The Anglo-Irish Treaty was finally signed at 10 Downing Street on 6 December 1921. During this period, Lavery, encouraged by his wife, became more interested in his Irishness and Irish politics.

Between November 2021 and January 2023, the exhibition “Studio & State: The Laverys and the Anglo-Irish Treaty” was co-curated by the Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin, and the National Museum of Ireland. The exhibition blurb:

Studio & State explores events between July 1921, when the Truce was agreed in Dublin, and January 1922, when the Anglo-Irish Treaty was narrowly ratified in Dáil Éireann. It considers the role that John and Hazel Lavery played during the Treaty negotiations and how they negotiated the complex relationships between art, politics, and history. The Treaty signatories from both sides sat for Lavery, and during the negotiations, his London studio was an informal meeting place, in which Hazel Lavery played an influential role. John Lavery cast himself in the role of artist-diplomat and saw the studio as “neutral ground”. The negotiations for and signing of the Treaty were crystallising moments for Ireland in the twentieth century. The Treaty was both a vehicle of peace as well as a catalyst for civil war. Sir John Lavery’s paintings provide an unparalleled record of this pivotal moment.

In the 1920s, he painted portraits of leaders of the Irish Free State, such as Michael Collins. Lavery’s society and political portraits earned him a strong international following, and his work can be found in the National Galleries of Ireland, Scotland, Victoria (Melbourne), and Canada, as well as in the National Portrait Gallery in London, Tate Gallery, Victoria and Albert Museum, Musee d’Orsay, Uffizi, and Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh.

If Lavery found Collins of interest, so too did Lady Lavery. What truth there is to rumours about her relationship with the ‘Big Fellow’ is open to speculation, but one contemporary newspaper article called her his “sweetheart”, fuelling rumours of an affair, which he denied but she encouraged. Books on Collins have ignored the subject, claimed it as fact (A Great Beauty by A. O’Connor), or categorically denied it (Michael Collins and the Women Who Spied for Ireland by Meda Ryan).

Collins prophesied that, in signing the Anglo-Irish Treaty, he had signed his own death warrant. On 22 August 1922, he was assassinated by anti-treaty forces. Rumours of an affair between Collins and Lady Lavery re-emerged when a letter addressed to “Dearest Hazel” was found on his body.

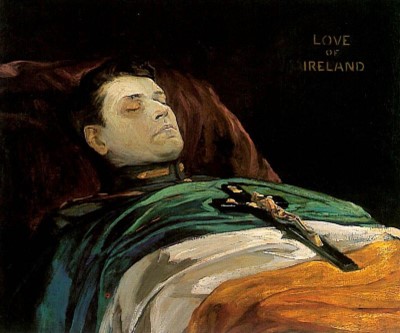

Lavery painted Collins lying in state, and again during his funeral mass in the Pro-Cathedral, Dublin.

This defining period of Irish political history also led to the International Olympic Committee affiliating the Irish Free State (via the Irish Olympic Council) as a member, and as such, the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris was the first in which an independent Ireland participated. Not only would Lavery represent Ireland as a competitor in the painting category of the arts competitions, but he was also selected as a judge. His painting, Steven Donoghue, did not win a medal, but his fellow Irish competitor, Jack Butler Yeats, won silver for The Liffey Swim.

Stephen Donoghue was an English flat racing jockey whose father was Irish. Among his achievements in the saddle are six Epsom Derby wins and ten Champion Jockey titles. Lavery’s near life-size painting of Donoghue depicted him in the jockey’s changing room at Epsom Racecourse, sporting the King’s colours.

Lavery also competed at the 1928 and 1932 Olympic Games in the renamed ‘mixed paintings’ category. For these two competitions, Lavery switched allegiance and represented Great Britain, re-entered the Stephen Donoghue painting in 1928 under the title Le Jockey Stephen Donoghue dans les couleurs du Roi, and, perhaps uniquely, is the only person to have a piece of art represent two countries at the Olympics.

We have to wait until the early 1930s for Lavery to finally get his easel out and paint the rowing pictures that make him worthy of a HTBS post.

Maidenhead lies on the River Thames, 40 kilometres west of central London. The first Maidenhead Regatta took place on the Cliveden Reach in 1839, only three weeks after the first Henley Regatta. One of HTBS’s most popular rowers, Bert Bushnell, raced for Maidenhead Rowing Club. I have fond memories of the regatta, winning a pot there in 2004; and of the town, spending a week there during the 2012 Olympics, taking the red-eye coach to Dorney via Windsor Racecourse.

Lavery exhibited his finished painting at the Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts in 1936 and gifted it to Glasgow Museums the following year. The museum’s website described the work (and, in doing so, solved a poser for me) as follows:

In 1932, inspired by the Maidenhead Regatta, he embarked on this large canvas, focusing on the curve of the River Thames and the fashionable crowds that lined its banks, sitting in deck chairs or on small leisure craft. Lavery excelled at painting fashionable crowd scenes like this, picking out details of costume and colour, his summary brushwork creating an air of excitement. In the foreground, a couple of female figures lounge in a skiff with an awning. This detail was not in earlier drawings and was included to add interest to the lower right section of the composition and enhance the air of elegance and pleasure. It appears to have been taken from an earlier study at Remenham. Although very English in subject, the painting is quite French in feel, reminiscent of the Impressionists’ views of the Seine, with its lively sky, poplars, and treatment of ripples and reflections in the water.

The painter as documenter of sporting events was a common practice even in the late 19th and early 20th century, and Sir John Lavery recorded many sporting events, especially the new sport of tennis during the late 19th century, throughout his career, including the Ascot and Epsom horse races and as pictured here, a summer rowing competition by Maidenhead Rowing Club.

My poser regarded the above painting, prints of which are for sale on several internet sites. Only one ‘Maidenhead Regatta’ is listed in the Lavery database, and I suspected that this version was by someone else cashing in on the Lavery name. The reference to ‘earlier drawings’ by the Glasgow Museum suggests that this is the original on-site composition by Lavery.

In 1934, during a brief period of respite from caring from his wife, who had only six months left to live, Lavery attended Henley Royal Regatta and made several outline studies that resulted in the above painting. Although quite blurred, you can make out two racing eights, followed by the umpire’s launch, approaching Phyllis Court Club.

When the painting came to the market in May 2000, it was again to Christie’s that the vendor turned, maybe hoping to realise a similar sum to The Bridge at Grez. In the end, it sold for £234,750, just shy of a million pounds less than its French cousin. Christie’s catalogue:

The picture is closely allied to Maidenhead Regatta (1932), which was shown at the Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts in 1936 (472) and donated by the artist to Glasgow Art Gallery the following year. A number of studies of figures lounging in pleasure boats, now in private collections, relate either to the Glasgow picture or to a proposed larger version of the present work. The present work is clearly separated from that in Glasgow by its scale and degree of finish. Here, even in old age, we see no diminution of Lavery’s power to respond to the visual chaos of a great public occasion.

I find it interesting that Lavery painted both Michael Collins and his wife, Hazel, coffined; Collins during his funeral mass in the Pro-Cathedral, Dublin, on 28 August 1922, and Lady Lavery (died 3 January 1935) at their home before her funeral at Brompton Oratory, Knightsbridge, London.

Both paintings were part of the Lady Lavery Memorial Bequest to the Hugh Lane Gallery. On its online collection page, the gallery describes the 1935 painting thus: Hazel would never have sanctioned a portrait that betrayed the ravages of her illness – a wish that Lavery respected. Painted by candlelight, the bedroom and draped coffin are described in lurid hues, which perhaps further reflect the artist’s sense of anguish and loss. Just as he had portrayed Michael Collins on a funeral bier in ‘Love of Ireland’ so too Lavery sought to commemorate Hazel’s devotion to Ireland in this painting, which he subsequently presented to the Hugh Lane Gallery [saying]: “It is for Ireland. She loved her country.”

She was buried in Putney Vale Cemetery in southwest London. In Ireland, a memorial service for her took place at the request of the government. During the Second World War, Lavery left London to live with his stepdaughter, Mrs Alice McEnery, in County Kilkenny, Ireland. He died there on 10 January 1941 and was buried at Mount Jerome Cemetery, Dublin.

But that wasn’t his final resting place. In death, as in life, Lavery’s loyalties were divided, and in 1947, he was reinterred beside his wife in Putney Vale Cemetery.

wonderful!!

djs