8 May 2024

By Göran R Buckhorn

Göran Buckhorn continues his article from yesterday how Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat (1889) inspired Constance MacEwen to write her novel Three Women in One Boat (1891).

The following is a summary of Constance MacEwen’s Three Women in One Boat: A River Sketch mainly concentrating on the “rowing parts” in the novel.

Just like Jerome K. Jerome’s novel Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog), MacEwen’s novel begins with three friends meeting. In Three Women in One Boat, the narrator Phœbe Winter has invited two friends, Selina Davidson and Sabina Ann Piplin, to her college rooms for tea. Phœbe needs some company and encouragement as we learn that she is to be “sent down” from her school. Selina happens to bring a copy of Three Men in a Boat, and the three women decide to replicate the three men’s boat trip, or as Phœbe puts it, “I am determined to show the world that what brains may have denied us three, muscles and biceps have done for us, and how we ‘three women in one boat’ didn’t make half such a mess of it as Mr. Jerome’s ‘three men in a boat’ – not by a long way.” To underline that women can be as strong as men, Phœbe describes Selina as a “great big creature”, and Selina proclaims her Englishness by saying that she is “English to the backbone.”

As Jerome’s men have an animal onboard their boat, Phœbe decides that she and her friends shall bring, not a dog, but her cat, Tintoretto, which we later learn “is twice as well-behaved as Montmorency.”

Selina has a trick up her sleeve when it comes to getting instruction in the art of sculling: her brother is a multiple sculling champion. He is the “winner of the Wingfields, the Diamonds, the Colquhouns,” which in other words are the Wingfield Sculls – the Amateur Championships of the Thames and Great Britain (nowadays named The British Amateur Sculling Championships and the Championships of the Thames), the Diamond Challenge Sculls at Henley Royal Regatta and The Colquhoun Sculls at Cambridge University – the Championships of the Cam. We never learn Selina’s brother’s name. He is called “the Champion,” alternately “Monsieur Wingfield,” “M. le Wingfield-Colquhoun-Diamonds” or “Champie” throughout the book. Knowing that MacEwen’s husband, Alfred Dicker, was the winner of all these three titles, we can assume that the author was inspired by her husband’s success at the sculls and maybe even used his knowledge of being a multi-time sculling champion while writing this novel.

On the three women’s first training outing, the Champion gives them advice on how to row: “keep under the bank, sit up, and don’t bucket – keep your stroke long and light, turn your wrists under, and get your hands away sharp; avoid racing, and ‘see that ye fall not out by the way.” When he pushes them off from shore, the narrator reads his lips, which “seem to form the words ‘Women can scull.’” The women’s first outing goes well and whets their appetite for sculling and their boat expedition on the Thames. Phœbe, who is the coxswain, proclaims that she is ready “to be cox for the World Championships.”

A reflection here is that the World Championships in rowing at this time were only held for professionals, not for amateurs. The “Professional Championship of the Thames” in the single sculls was held the first time in 1831. (The first Wingfield Sculls was held in 1830.) In 1863, the professional championship became the Championship of the World when Richard Green of Australia raced Robert Chambers, the celebrated sculler from the River Tyne. The Englishman won the race.

The amateur men had to wait till 1962 before they could win the title for the World Championships while women had to wait until 1974. Before that, in Britain, Henley Royal was regarded as the finest regatta in the world, so to win the Diamonds would be equivalent to the world title in the single sculls for amateurs. In the rest of Europe, rowing nations competed in the European Championships, which started in 1893, the year after the International Rowing Federation (FISA; now called World Rowing) was founded. The first non-European crew racing – and winning – in the European Championships were an American eight from Vesper BC in 1930. And, as we know, since 1900 crews could race to become Olympic rowing champions – the best of the best.

On a hot Monday in September at Richmond Bridge, it is time for Phœbe, Selina and Sabina (and Tintoretto) to take on their self-assumed challenge to prove “that three women are equal to three men in the boating line.” They go aboard their Thames skiff, The Sirens, which has less equipment than ‘J’, George, and Harris had on their expedition, and set out on their river adventure.

Their first encounter with another boat is not a lucky one. Phœbe is daydreaming and steers The Sirens into another boat with a man and his wife. Our narrator describes them as if they were from a Punch cartoon: in the boat “sat an old gentleman in swallow-tails and white tie and parson’s crush-hat,” and his wife is a “madam” who “had fought Time not with weapons intellectual or spiritual, but with cosmetics and unguents.” The women in The Sirens quarrel with her, and they praise the road they have taken, the one of “healthy womanhood.” To feel stronger, they burst out in a women’s equality song. The second verse goes:

We are glad with the joy of a new day’s birth,

We are free with the freedom of women’s worth,

We are strong with the strength of the river’s breath

Three women afloat in a boat, Yo-ho !

And the third goes:

The kingdom of women has yet to come,

The race for wealth is not half begun;

In the heart of a man there is room for all,

Three women afloat in a boat, Yo-ho !

An old man fishing from the shore approves of what he sees and hears. He shouts encouraging words and applauds their sculling and song. A little later Phœbe steers into shore where an old boatman helps them to dock their boat. He also expresses his approval of their sculling, “he didn’t see ‘why womenfolk shouldn’t row a boat as well as menfolk.’” The three women take a room at a haunted inn where they meet a ghost at night. In the morning there is a knock on the door and a German nobleman, “Hereditary Grand Ducal,” enters their room with three bouquets of flowers. He pays tribute to the ladies and their country: “You English people are to this day an heroic people, also an athletic people. I insist on the athletics. The oar is the national safeguard against horrible luxury which overtook Rome and killed Greece.” The German nobleman hopes to see them again on the river, he bows and leaves.

Out on the water again, the river is crowded with boats. The Sirens moves away from the scullers, but one “gentleman” is determined to race them. His shell is named Pecksniff’s Dream which makes the narrator reflect: “a curious name for a boat – some connection with Dickens, evidently.” And that is correct: Seth Pecksniff is the great villain in Charles Dickens’s picaresque novel The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-1844). Remembering what the Champion has told them, Phœbe forbids racing, but when Selina and Sabina put more power to the sculls, Phœbe is soon caught up by the thrill of speed and strength, “I went in for the madness of pure sport,” she says and cheers on her scullers in the boat: “Go it, Sabina! Well done, Selina! Never be beat! Don’t be beat! Go it! Go it!”

It almost sounds like a passage from Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), where Stubbs, second mate aboard Captain Ahab’s whaling ship Pequod, urges his men when they row their whale boat toward a pod of whales:

Pull babes – pull, sucklings – pull, all. But what the devil are you hurrying about? Softly, softly, and steadily, my men. Only pull, and keep pulling; nothing more. Crack all your backbones, and bite your knives in two – that’s all. Take it easy – why don’t ye take it easy, I say, and burst all your livers and lungs!

In The Sirens, Phœbe continues to urge on her crew: “Go it, Selina! My splendid Selina! My clever, darling Sabina, go it! Noble girls! Noble Bereans! Won’t I fête you after this!”

The Sirens is gaining speed: “Then came a spurt from Selina and Sabina which would have done credit to a ‘Varsity finish.” Phœbe is absorbed by the race and admires her crew’s “coolness [when] they put on a tremendous stroke – I should think nearly forty to the minute.” Phœbe shows that she is aware of the Punch terminology of the day: “Now our boat commenced to forge ahead. I looked for our ‘’Arry’. I saw symptoms of distress; his mouth was open.” When The Sirens is a boat length ahead of Pecksniff’s Dream, Phœbe decides to try an old trick of the trade of the watermen and professional scullers. She steers The Sirens across Pecksniff’s Dream’s course to take his water, or as Phœbe puts it, “to give him our wash, and so dishearten him as much as possible.” Her plan works and the sculler gives up and the victory is theirs! After the race Phœbe feels at peace with everybody, “even poor dear ‘’Arry.’”

See a Punch cartoon from 1907 when ‘Arry and his ‘Arriet are out boating for the first time, here.

After a fishing endeavor, Phœbe begs Selina to tell the story of how the Champion won the Diamonds. Selina was present at the regatta in Henley-on-Thames and begins by saying that “a more modest fellow than my brother never championed the Thames.” She paints some atmosphere pictures of Henley Royal Regatta, “Henley – gay Henley”, the famous regatta where not much has changed over the years. There are people on the banks, and “Henley bridge is massed with heads, […] strawberry-sellers [- – -] flannels, gay straws, blazers distinctive of colleges, clubs, schools, light blue, dark blue, each colour as significant to boating men as the degree of a parson to a ’Varsity graduate.” She is not forgetting to mention the obvious, that “there’s a grand display of bare legs, both in the boats and on the banks.”

Selina continues to relate her brother’s first race in the Diamonds, though states that the single sculls races are “pair-oar-races”, which is a widespread mistake made by non-rowers. There are three competitors in the Champion’s race for the Diamonds title. One is the holder of the Diamonds, the second “a well-tried man”, and Selina’s brother, the novice. The latter is “walking over the course with long, swinging, powerful strokes; he is sweeping over the water, his cherry-coloured flag waving gaily in the nose of that racing craft.” He is the first to cross the finish line, and “this was the beginning of the long series of triumphs for which our Champion is famous,” Selina says. Whereas there are only two boats in each race at Henley nowadays, in the final of the 1874 Diamonds, Alfred Dicker had two other scullers in the race. The “cherry-coloured flag” on the Champion’s boat might well be seen as the colour of Lady Margaret, Dicker’s club.

The next morning, a mile beyond Windsor, the ladies take a swim in the river, which makes Phœbe reflect about their bathing costumes and thinks about “old Socrates, or Diogenes in his tub.” Phœbe thinks Sabina looks silly, especially when she is trying to talk about the philosopher Schopenhauer with her mouth full of water. At breakfast they get out their frying pan to try to copy George, “(I think it was ‘George’) to a T. Frizzle, frizzle, frizzle” as Phœbe puts it. When breakfast is over, they begin to talk about their plan for the day, or as Phœbe says, “L’homme propose, mais Dieu dispose.”

Suddenly, a steamboat approaches The Sirens from aft – it is Hereditary Grand Ducal. He is delighted to see “the aquatic Fräuleins,” and after some polite words, he adds “I have a note-book always at hand. […] I shall possess myself of the wise, witty, and tender sayings of the fair lady scullers! I shall absorb them into books. We authors live to write […].” (Is this the voice of Constance MacEwen proclaiming her love for her chosen trade?)

Hereditary Grand Ducal, or Fritz, insists on towing their boat to his house by the river in Sonning, so they can meet his sister, Xenia. On their way to his house, Sabina is on deck, while Phœbe takes a nap on one of the couches in the salon onboard the German’s steam launch. Phœbe wakes up in the middle of Fritz’s proposal to Selina, but not to interfere she pretends to be asleep.

A “char-a-banc” with four horses picks them up to drive them to Fritz’s house, but before they arrive, they stop at the post office to send some telegrams to friends and relatives, telling them that they will arrive at Richmond Bridge that night. At the house, they are well received by Fritz’s sister Xenia.

In the late evening at Richmond Bridge, a little group of people have gathered to meet the three women when they row the last stretch of their trip in The Sirens. A friend of Sabina’s, a man called Calendar, is waiting for her. In the beginning of the story, we learn that Sabina met him at tennis, and he has a big beard. Sabina is fond of him, although he “has reached the dangerous land of forties.” (MacEwen was 41 when Three Women was published.) For Phœbe, the Champion is waiting, which makes her sigh, “if he should ever care for me, with that strange unexplained love which makes for matrimony, be sure and let me be rechristened Rowena, not Phœbe, for a Phœbe I never was and never could be.” And with these words the story ends.

While it almost takes us to read a third of Three Men in a Boat before anyone takes a stroke, MacEwen does not waste any time, the three women are in the boat, sculling on the river, already in Chapter 3, page 21, in Three Women in One Boat. Even if Phœbe, Sabina and Selina are sculling in a pleasure boat, they are early on introduced to competitive rowing: by the Champion’s presence, the story about his race in the Diamond Challenge Sculls, the descriptions of Henley Royal Regatta and when the three women are racing against the sculler in Pecksniff’s Dream. Jerome’s novel is not lacking moments of rowing as a sport, if by that one means rowing in narrow racing shells. It is just that ‘J’, George, and Harris are never racing in their skiff during their trip between Kingston and Oxford. They talk about other occasions when they have been out on the river, like when George was on his first outing in “an eight-oared racing outrigger” when he “immediately on starting, received a violent blow in the small back from the butt-end of number five’s scull, at the same time that his own seat seemed to disappear from under him by magic, and leave him sitting on the boards. He also noticed, as a curious circumstance, that number two was at the same instant lying on his back at the bottom of the boat, with his legs in the air, apparently in a fit.”

It is understandable that the three men are not racing as this would contradict the idle spirit of the book. They have the chance to watch some rowing races as they arrive in Henley-on-Thames when the town is getting ready for the regatta, but they make no effort to stay and watch the races.

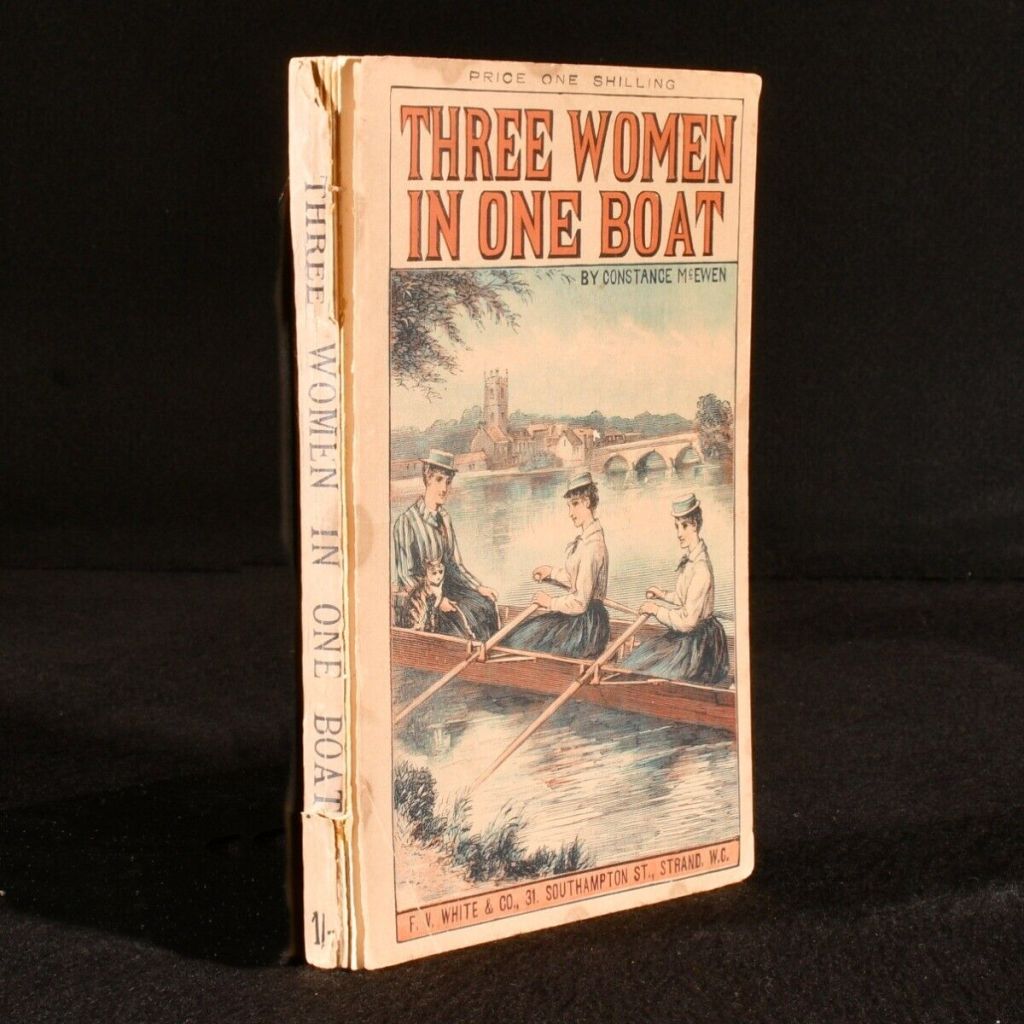

The narrator in Three Women in One Boat has, of course, a positive attitude towards women rowing. Women do have a place in a boat in Jerome’s book, but not at the sculls. They are there as someone for the men to impress or to have as Belles des Bateaux. However, women should be correctly dressed in a “boating costume,” which according to Jerome, or ‘J’, should be a “costume that can be worn in a boat, and not merely under a glass case.” He tells the story how he and a friend took two ladies for a river picnic and how the ladies were dressed “all in lace and silky stuff, and flowers, and ribbons, and dainty shoes, and light gloves.” Not surprisingly, the trip ended in disaster. There is no dress code given in MacEwen’s novel, but the cover illustration gives us a hint, at least what the artist of the cover thought that women should wear in a boat. In June 2008, Chris Partridge published an article on his blog Rowing for Pleasure quoting a June 1889 article from the American magazine The Outing, “Rowing as a Recreation for Women”, by Margaret Bisland. In her article, Bisland discusses rowing techniques, boats and women’s clothing at an outing. See Partridge’s article here.

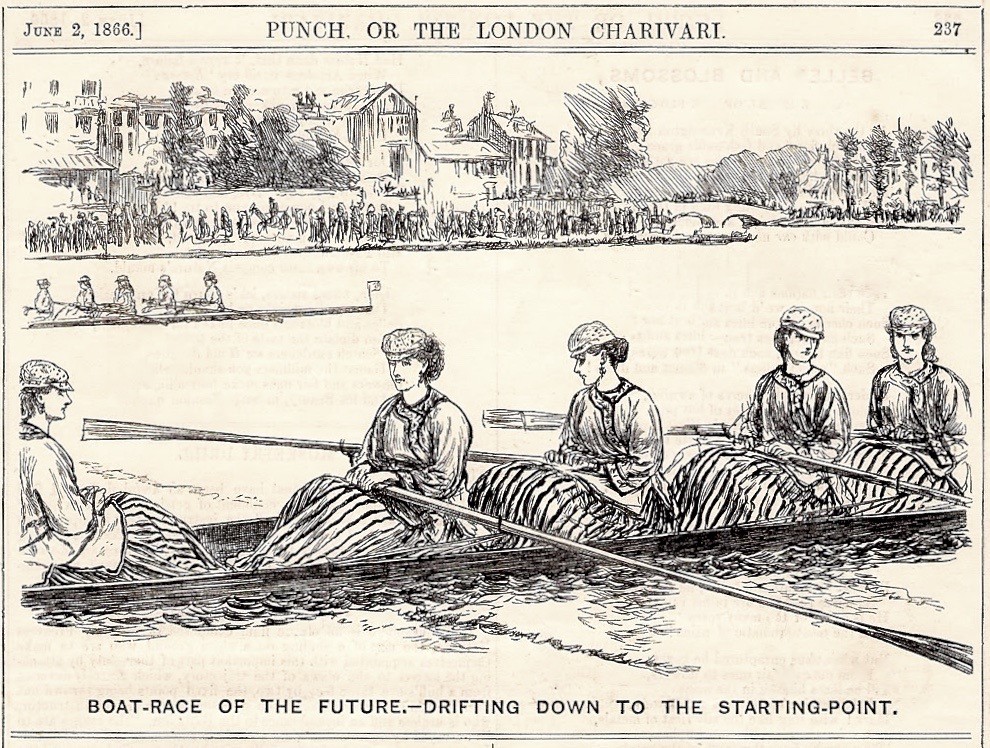

At the time when Three Men and Three Women were published, women at the oars were still a rare thing to see on most waterways in England, other European countries and the United States. Women had, however, made appearances on the water, showing that oar power was not only an activity for men – and it was not an athletic movement on a whim; women’s rowing was here to stay. In 1875, Wellesley College in Massachusetts started a rowing program for women. The following year, two women competed in a single sculls race on The Monongahela River at Pittsburgh. One year after MacEwen’s novel was published, in 1892, four women in San Diego, California, founded the first U.S. women’s rowing club, ZLAC Rowing Club (after the founders’ first names, Zulette, Lena, Agnes, and Caroline). The year after, Newnham College, Cambridge, in England, organized a “boating society” for women. The London-based Hammersmith Sculling Club, which started in 1896, was a club for women – from 1901 also for men. (The club changed its name to Furnivall Sculling Club after its founder, Frederick Furnivall, in 1946.) By the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, the Bicycle, Barge and Canoe Club was established in 1897, but it almost immediately changed its name to the Sedgeley Club, which was for rowing women.

It seems to be a happy ending for the three women, especially if we regard the novel as a “romance”. Selina gets her German Duke, Sabina her Calendar, and our storyteller, Phœbe, will hopefully marry Selina’s brother, the Champion. However, the ending seems to be far away from how the novel began, as a “propaganda book” for women’s equality and freedom, “the freedom of women’s worth” as the three women sing in the “equality song” on the river.

The author Constance MacEwen (or if you prefer, the narrator Phœbe Winter) raises the question of equality between men and women by using the most popular and manly sport of the day, rowing, as her tool. MacEwen demands, through the voice of Phœbe, that women should have the same right as men to be out rowing – and racing – on the river.

One difference between Jerome’s novel and MacEwen’s romance is that, while the first mentioned has stood the test of time – it is remarkable that almost 135 years after it was first printed, Jerome’s book still feels fresh with its wit and “new humour” – the latter has not. The time has not been so kind to MacEwen’s novel. To a reader of today, her book has an old-fangled, stuffy Victorian touch to it. A rowing scholar might find its “rowing parts” interesting, but it is not a funny book for the modern mind. Maybe it was once regarded as entertaining and popular among the readers – after all, there were at least three printings of the novel – but it is hard for us to see. Nevertheless, MacEwen should receive some praise for depicting rowing and racing scenes which at least rowing historians, scholars and devotees can appreciate and discuss in the 21st century.

A few weeks ago, one of HTBS’s loyal readers, Bernard Hempseed of New Zealand, who is a rowing historian, author of Seven Australian World Champion Scullers (2011) and has written articles for this website, kindly sent HTBS a PDF of Constance MacEwen’s Three Women in One Boat. With the help of the technology OCR (Optical Character Recognition), Bernard has reproduced MacEwen’s novel so HTBS can share it with its readers. Get your own copy of Constance MacEwen’s Three Women in One Boat here (it prints out nicely on A5 paper).

Notes:

My warm thanks to Bernard, who has worked hard with this cultural endeavour. Thanks also to rowing historian Tom Weil, who allowed me to borrow his copy of Three Women in One Boat when I wrote the first version of this article more than a decade ago. Tom also gave me that following information of Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat: First edition and printing published by J. W. Arrowsmith, Bristol, September 1899. Green cloth (second edition, changed to blue), decorated and lettered in black, publisher’s device and lettering to spine in gilt. 315 pp, 3 pp ads. No 11 not in publisher’s address on title page, Quay Street, but 11 Quay Street to ads. “The ads on the rear pastedown are for Prince Prigio and Jonathan and his Continent, both ready in October.” Shorter list of novels on first page of ads at rear. Moon showing in illustration on p. 20. For the true first edition only 1,000 copies were printed.

Three Women in One Boat – A River Sketch by Constance MacEwen was published by F. V. White & Co., 31 Southampton St., Strand W.C., 1891, soft cover, 1 shilling, misspelling of author’s name, “Constance McEwen”, on the cover of the book, 118 pp, nine pages of advertisements (3rd printing: 3 pp with ads in front of book, 4 pp with ads in back). At least three printings were published of MacEwen’s novel.