6 May 2024

By Tim Koch

Tim Koch is Roman around.

News that stunning frescos have been uncovered in a new excavation at Pompeii, the ancient Roman city buried in a volcanic eruption from Mount Vesuvius in AD79, reminded me of some other Roman wall paintings, ones of interest to HTBS Types. They were produced around one hundred years after Vesuvius and were found on the via La Portuense in the river port of San Paolo, Rome.

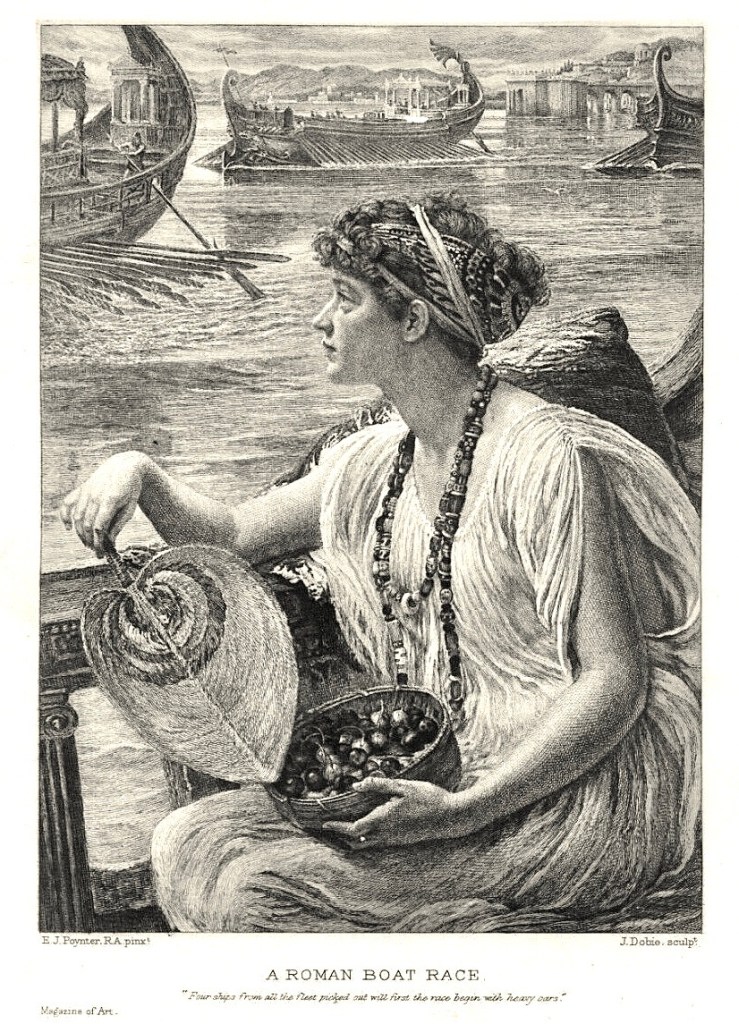

Below is a rather more modern picture (1890) by Sir Edward Poynter. It is a rather fanciful depiction of a Roman boat race inspired by one translation of a quote from The Aeneid, the epic poem completed two decades before Christ: Four ships from all the fleet picked out will first the race begin with heavy oars.

Lacking a classical education or access to the know-alls of Delphi, I turned to today’s Oracle, Wikipedia, for the information that the Aeneid is a Latin epic poem in twelve books written by Virgil (Publius Vergilius Maro) between 29 and 19 BC. Ostensively, it relates the travels and experiences of its Trojan hero, Aeneas, but its main purpose was as a foundation myth, a glorification and exaltation of Rome and its people. Aeneas embodies the most important Roman personal qualities and attributes, particularly the Roman sense of duty and responsibility that Virgil thought of as having built Rome.

In Book V of the Aeneid, Aeneas holds games in Sicily to honour his father who had died there a year before, and the events included a boat race, a running race and a boxing contest.

In 2015, an eclectic website called The Grønmark Blog posted a piece titled,The best ever description of a boat race? The Aeneid, Book V. The author, the late Scott Grønmark, clearly a well-read man, wrote that the race between four Trojan ships was “undoubtedly the best description of a sporting event I’ve ever read”.

Grønmark quotes all of Virgil’s 2,000 words (John Dryden’s translation) describing the race and they can be read in full here. It may be beneficial to read a description of the race in prose before (or instead of) attempting Virgil’s poetic version.

The four competing boats were Chimaera, captained by Gyas; Scylla, captained by Cloanthus; Centaur, captained by Sergestus; and Pristis captained by Mnestheus.

The Chimaera was the largest vessel, a trireme fifty metres in length with a triple line of oarsmen and oars rising in three rows. The other three vessels, Pristis, Centaur, and Scylla, were biremes, somewhat smaller with two decks of rowers.

The boats in the race are to go out to sea, round a half-submerged rock and then try to be the first to make it back to shore.

For Virgil the first half of the race is not important, although he says that Cloanthus’ rowers are better, but because their ship is slower, Gyas takes the lead as they approach the turn. Gyas keeps telling his pilot, Menoetes, to come in close around the rock, but he is afraid of crashing and makes a wide turn.

This allows Cloanthus, the captain of Scylla, to squeeze in between Gyas’ Chimaera and the rock, making a sharper turn that puts him in the lead for the homestretch.

Gyas is so angry that he throws Menoetes overboard and takes the tiller himself. There is loud laughter from the Trojan spectators when Menoetes eventually surfaces and clambers onto the rock.

Of the two ships in the rear, Centaur leads Pristis until her captain, Sergestus, tries to cut the turn too close, and smashes up his oars against the rock. Mnestheus’ Pristis thus rounds the turn ahead of Sergestus.

Next, Mnestheus passes Gyas, who is having trouble acting as captain and pilot at the same time.

Now it is Mnestheus and Cloanthus that are competing for first place.

Cloanthus prays to Neptune, promising to make offerings to him, and comes from behind to win.

Thus, Cloanthus’ Scylla comes in first, followed by Mnestheus in Pristis, Gyas in Chimaera, and with Sergestus bringing up the rear in his disabled Centaur.

Aeneas, impressed by the hard fought race, gives prizes to each of them.

Below is an extract from Dryden’s translation of Virgil describing part of the first half of the race and these are the lines most commonly quoted. The account of the second half of the race is probably more gripping though arguably less accessible. The forced rhyming is a little McGonagall-ish, one of the more modern translations is by AS Kline.

The common crew with wreaths of poplar boughs

Their temples crown, and shade their sweaty brows:

Besmear’d with oil, their naked shoulders shine.

All take their seats, and wait the sounding sign:

They gripe their oars; and ev’ry panting breast

Is rais’d by turns with hope, by turns with fear depress’d.

The clangor of the trumpet gives the sign;

At once they start, advancing in a line:

With shouts the sailors rend the starry skies;

Lash’d with their oars, the smoky billows rise;

Sparkles the briny main, and the vex’d ocean fries.

Exact in time, with equal strokes they row:

At once the brushing oars and brazen prow

Dash up the sandy waves, and ope the depths below.

Not fiery coursers, in a chariot race,

Invade the field with half so swift a pace;

Not the fierce driver with more fury lends

The sounding lash, and, ere the stroke descends,

Low to the wheels his pliant body bends.

The partial crowd their hopes and fears divide,

And aid with eager shouts the favor’d side.

Cries, murmurs, clamours, with a mixing sound,

From woods to woods, from hills to hills rebound.

My other attempt at understanding The Aeneid was in 2018: Virgil and The Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy of HCBC.

*Latin meaning the rowing of oars (or the beating of wings).