27 February 2024

By Hugh Matheson

Hugh Matheson, Old Etonian, three-time Olympian, author and owner of the Thoresby Estate has some thoughts on privilege and class in rowing.

I read Tom Daley’s contradiction of the claim, in both the book and the film of The Boys in the Boat, that these were farm boys who took on the pandered elites of the US east coast and Hitler’s favourites, the ‘vaunted’ German team, to win Olympic gold, with cheering pleasure at the justice of his point.

In the film, the Washington success is attributed directly and only to the backstory of the “sons of loggers, shipyard workers and farmers”. Daley suggests that the film’s producers picked the idea from the jacket blurb of the book, rather than the deeply researched text itself. Wherever it came from, he demolishes that thesis, showing that the Boys were mostly from the aspirational bourgeoisie and among the only 7% of pre-war US school leavers who went on to university.

What was remarkable about the ’36 crew was that they overcame the disadvantages of their middle class comforts and got tough and strong enough to win through the escalating series of trials, until they reached the Olympic final. They were also remarkably lucky in having a coach as wise and straight as Al Ulbrickson. The book and in places the film, show him, plausibly, as the difference between nothing much and gold.

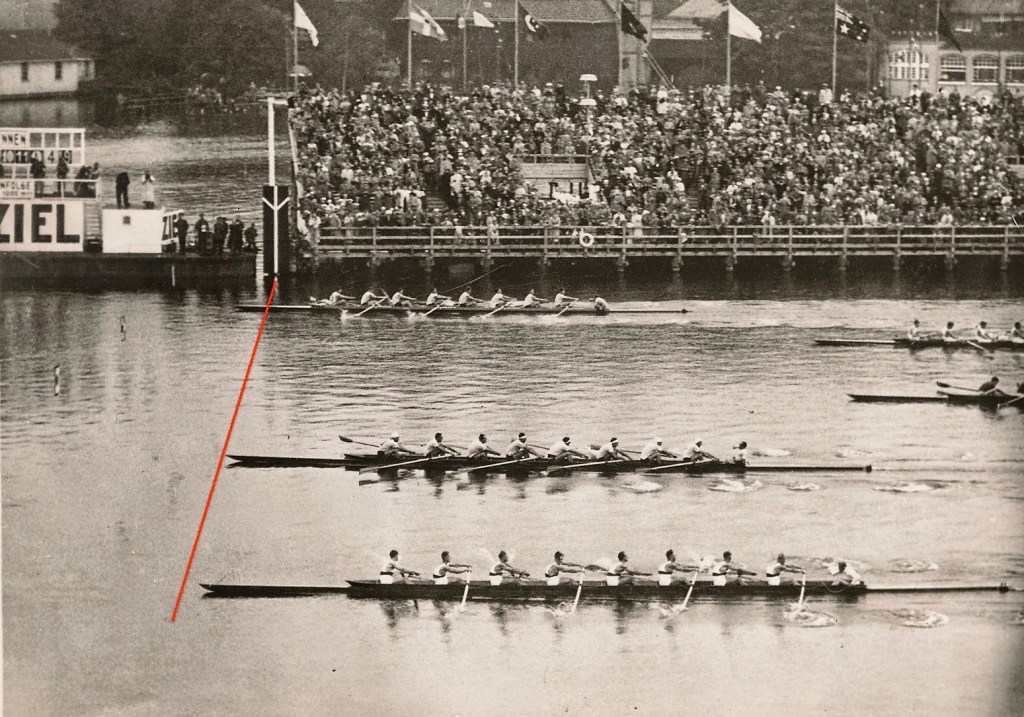

At the Grünau Olympic course they overcame, in a photo finish that would not meet today’s World Rowing standard, the forza della natura, Scarronzoni, a crew of genuine longshoremen from the Livorno working class. The Scarronzoni got the name from their inability to row in a straight line, often creeping sideways (scarrociare in Italian) as the pressure on port and starboard varied. Their boat speed came from endless competition in risiatori, the boats which raced out to incoming merchantmen to win the right to unload when the ship reached the dock at the Tuscan seaport of Livorno.

These were hard men because they did all this in ferociously hot summers, while also being poor enough that their diet was not capable of supporting the 7000 calories a day required to do hard manual labour through the working day and follow it with Olympic level training in the evenings.

My own irony hackles were aroused by Daley’s picking apart the Washington boys from the hard places idea, because my Eton crew of 1967 was actually and truly built around six country boys, born and bred on the land. That crew won the Princess Elizabeth Cup at Henley and after winning a national trial, went to the first FISA Junior Regatta on the Küchensee at Ratzeburg.

Raced over 1500m, the Eton crew was stuck in the middle of the field until, about 350m from the finish, the stroke of German crew, which had looked strong in the heats, but was now hanging onto a diminishing lead, crabbed calamitously and Eton swept through to win by a length.

It was a quick crew to be sure, but its success was perhaps flattered by the German decision to hold back their “Babes” squad until the Bosbaan championships in 1968. There they beat another good Eton crew by 18 seconds (okay – for the pernickity, only 17.5 secs.).

The origins of the ’67 crew was that six of the eight came from landed estates, or by any measure, large farms. I, we, had grown up expecting to rebuild stone walls, dig ditches and to stook sheaves (look it up). I rowed at five and spent a week in the summer of 1966 at the estate of the bow man, spade in hand, digging out 500m of a mill race, amounting to 250m3 of sticky mud and tangled reeds.

For privilege and elite expectation there are few higher categories than boys who go from large landed estates to Eton and then Oxford or Cambridge. That advantage carried straight through to crew. Self-selected by their inability to catch a cricket ball, they used their excellent diet, fresh food from their own gardens and stock yards, and strength developed by helping their father’s staff hew wood and carry water, to gratify their hunger for success.

The crew did almost no land training but had spent three or four years dragging heavy, clinker whiffs, built in the Eton workshop, against the stream from the boathouse at Windsor Bridge. From joining the school at thirteen, most had grasped at the opportunity to scull six miles to Queen’s Eyot where they would be served any amount of beer, regardless of age. Coming home, although downstream, sometimes took longer than going.

Any examination, on a reasonably sociological basis, of the origins of rowing champions will show an overwhelming preponderance of the middle and upper classes of all the competing nations. It’s an expensive sport. Boats, boat houses and the rest cost middle class amounts of investment. Most countries have, in recent years, introduced programmes to entice less privileged youths into the sport, frequently in response to the taxpayers’ sense of being taken for a ride in sponsoring the already fortunate to play games on the water. (UK 4 year budget for rowing to the Paris Olympiad £22m.)

Oh, and George Pocock, who features larger even than Ulbrickson, in the book and the film, learned his boat building craft in his family’s workshop at …er…Eton, before emigrating to Washington and building that Husky Clipper for the ’36 Olympic crew.

Pocock grew up speaking with the gentle rounded vowels of the Berkshire riverside but, with exposure to the entitled drawl of the Eton boys he coached, he adapted his voice to capture the assumed authority, and with similar guile, began drafting the epigraphs with which Daniel James Brown opens every chapter.

I was disappointed by the film because it persisted with this mistaken belief that U. Wash. was more richly populated by boys who had to work their way in manual jobs through school than anywhere else on the East or West coasts of the United States. If that is unevidenced nonsense, it was a particular pleasure to read Daley take it apart. Three cheers, for the privileged Princetonian.

Excellent writing Hugh, as I would expect. Really enjoyed it. Thank you.

Rather disappointing that Hugh chooses to ignore who was the coach of the Italian Olympic VIII of dockers; another professional waterman spurned by the English praetorian guard.