20 February 2024

By John Drew

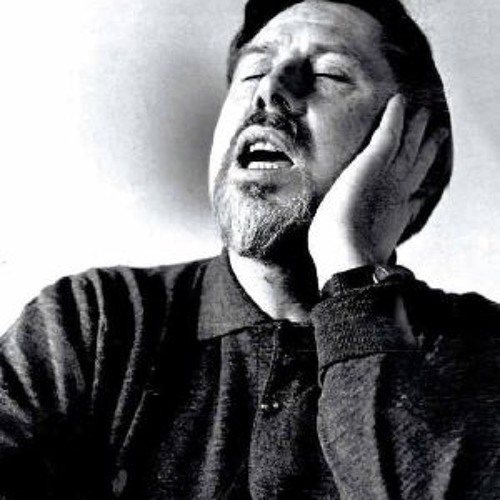

How to Hear the Thames Sing – John Drew writes about Ewan MacColl’s Master Class in writing a love song.

Five hundred years ago, Edmund Spenser wrote a poem to celebrate a wedding taking place beside the River Thames. Each stanza ends with the refrain: Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song.

We don’t write Elizabethan-style poems any more but the first great Modernist poem, T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland, picks up on this catchy refrain. And so does a love song by ‘Sixties folksinger Ewan MacColl. If you know a catchy line – or two or more – from the past, go with it. The something inside you that responds to it means it is part of you too.

A good love song does not want soggy, abstract images: I love you, scooby-dooby-doo. Boo hoo hoo. Of course, boo hoo, we’re crying inside – or out – but a good song or poem requires the distancing of a concrete image. Together with a good tune or beat, like a ballad.

For those of you who don’t want to riff off the rap form used by Spenser’s Elizabethan contemporary, John Skelton, the ballad is a hardy perennial.

Poets may care to eavesdrop on this note for song-writers. If you happen to be one of those who has been told you cannot hear the native stresses of the English, the best way to attune your ear to them is by singing ballads (once you have stopped chanting nursery rhymes) – as the English themselves do since their stresses in ordinary speech are not iambic.

Rivers? The world is full of great rivers much longer and much wider than the Thames. The Thames is just a ditch by comparison but the global metropolis of London being situated on it has given rise to so many stories it has become mythic. Especially, in imperial times: read, if you haven’t, Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness.

Mythically, rivers are invariably seen as feminine, being fluid, as against mountains being fixed, inflexible – and hence – if you’ll pardon the stereotype – masculine!

And so to Ewan MacColl. He wants to write a love song and he picks up this line of Spenser’s. He wants only the first half of it for his refrain (the last half can simply echo in your head if you know the original). He also changes the word “run” to “flow” – as many of us do when misremembering the line. Sweet Thames, flow softly.

Ewan adds a variant line to tee up this refrain, one that emphasizes the conventional femininity of the river: Flow, sweet river, flow. While the dominant image for the – always unknown, taken for granted – woman is established as the river, that for the man, the singer, is quickly shown to be that of London.

Ewan met his girl – “me girl”, he says with a touch of Cockney accent, dialect always good in ballads – on Woolwich Pier, beneath the big crane standing. We are still – just – in the days when big ships from across the world came up to the East India and West India Docks. His love for her passes all – rhyme can be effective when it is not clichéd and banal – understanding.

He took her sailing on the river, proclaiming that London Town was his to give her. Verse by verse, four beats to each line, his courting continued apace as they proceeded up the river on the flowing tide, passing well-known landmarks.

At London Yard he took her hand, at Blackwall Point he faced her, at the Isle of Dogs he kissed her mouth and tenderly embraced her.

This is followed by a stanza containing the lines of the refrain:

Heard the bells of Greenwich ringing, flow, sweet river, flow, all the time my heart was singing, sweet Thames flow softly.

You will get the idea by now. Keep going upriver through London, giving your girl this and that part of riverside London as a brooch, it may be, a ribbon, a necklace, a ring, a bracelet.

He kissed her once again at Wapping and after that there was no stopping – flow, sweet river, flow – and he, having declared his love for her from Rotherhithe to Putney Bridge, they leave London behind as she from Kew to Isleworth swears her love for him.

But then, just when love had set his heart a-burning he, blinded by this, never saw the tide was turning. The voice of the singer, unaccompanied, becomes prosaic as he recognizes winter’s frost has touched his heart. Now creeping fog is on the river, sun and moon and stars gone with her. That’s it, all over with the sweet river softly flowing. Swift the Thames runs to the sea, bearing ships and “part of me”.

So, there it is. What more do you need? Ewan MacColl’s master-class in how to write a love song – or, if you like, a poem. He has an idea and a concrete image for it – what T.S. Eliot calls an objective correlative – and it is extraordinary how much rhythm gets generated by your delight once you hit upon a fresh idea.

Ewan takes a traditional ballad form and steals a good line – call that tradition – from an old love poem. The theme is also conventional enough. Love starts in wonder and ends in tragedy. Or at least pathos. Nothing new there.

What is new is that the writer finds a fresh idea and delights in developing a love poem out of the image of the flow and ebb of a river through the riverside districts of a city. Perhaps you might do something similar with any river in your own vicinity, be it the Mississippi, the Mekong or the Mystic? The impulse comes from hitting on a new image for yourself.

If you are “the girl”, you may want to turn Ewan’s perspective – from the as yet unliberated Hippy ‘Sixties – inside out and upside down. Wretched feller, bothering you on Woolwich Pier.

Wendy Cope writes a wry love poem of sorts also set in London. Positioning herself at a bus stop, she compares “bloody men” to bloody buses that never seem to come along. Or, if and when they do, they appear in convoys of three. Not that Cope’s perspective will be yours either. Times have changed, places are different.

Wherever and whenever you are, the principles of composition, image and rhythm, remain the same. And reflecting on the unhappiness of being in love, the sheer cussedness of life, is an ideal time to enjoy writing. One of Thomas Hardy’s wives once remarked on seeing him happily writing a sad poem.

Therapy. Go for it.

John Drew’s latest publication is a book of essays with a Bengali flavour, Bangla File (ULAB Press, Dhaka, 2024).

Wonderfull. Don´t forget the poetry while boating on a river. And read Joseph Conrad: “And this once was the darkest place on earth…”