13 February 2024

By Chris Dodd

Tim Koch has proposed that 50 HTBS tags in 11 years and Malcolm Knight’s photographic gallery of the making of the movie calls for a line to be drawn under coverage of The Boys in the Boat and their trip to Berlin in 1936. Chris Dodd begs to differ. ‘The Boys in the Boat row on and on’ says he.

Great expectations! A movie of The Boys In The Boat, that eye-watering book by Daniel James Brown, narrated through lenses by George Timothy Clooney, an insightful and multi-talented filmmaker. A project designed to bring to the box office the Great Depression, the Pacific Northwest Frontier, the Olympic Games, Nazi Germany, roots and branches of Scandinavian migrants, coast-to-coast college crew rivalry, a varsity showdown at Poughkeepsie on the Hudson, coaching by the crafty ‘Dour Dane’, Alvin ‘Al’ Ulbrickson, philosopher’s wisdom from Eton wonder woodworker George Pocock, the Seattle students who manned the eight-oar that George fashioned for them in red cedar, a boat aboard which the crew and coxswain Moch prepared to power through the waters of the Langer See and raise the Stars and Stripes to the top of the tallest pole at the medal presentation.

Their triumph infuriated the Führer, and his fury was witnessed by a massive crowd on the banks at Köpenick, a crowd who had just witnessed the Husky Clipper’s narrow victory.

But of course, I set myself up for disappointment. I’m no cinematographer, but I can see what a difficult task I set for the movie-makers when I presented them – metaphorically speaking – with my potpourri.

Clooney chose to leave out several of the big issues while concentrating on the trainer, his boys and the 1936 Olympic regatta. And much of his film strikes home, especially if you are au fait with rowing crew selection and the goings on at the 1936 Olympics. There are some marvellous factors caught in the film, especially for rowing people. The casting is superb, the rowing passes muster, the sets pull you straight into the depression of the 1930s and the sweat-and-sawdust fug of the crew shed and boat shop on the University of Washington’s campus. The two eights that Bill Colley built in the style of the 1930s at his workshop on the River Thames at Richmond, England. The tensions raised by crew bonding and learning to trust under pressure come over well, and thanks to newsreels there is no question whose country you are in when watching the Olympics in 1936.

I have been fortunate to see many of the places depicted in film at first hand – although it must be said that as ancient as I am, I don’t go as far back as 1936. I have been to an open day regatta and parade on the Montlake Cut in Seattle, the canal that links freshwater Lake Washington to saltwater Lake Union on Puget Sound. I have visited Eton’s ‘Rafts’ boathouse to see where Pococks ruled their era of boat building business in the shadow of Windsor Castle. I have stood in the Berlin Olympic stadium and imagined being among thousands of enthusiasts greeting Hitler by what a German’s right arm was for back in the opening ceremony day. I have sailed out of Hamburg’s docks and toured ‘boathouse row’ where the Olympic regatta took place at Grünau. I’ve caught sight of the Ivy League’s favourite water on the Hudson at Poughkeepsie. I have visited Washington’s West Coast competitors.’

So I was well set up for the arrival of the story of the boys in a boat. Clooney’s cuts reduce the British episode of the 1936 Olympics to one sentence. There were seven rowing events in Berlin and the Germans won the first five finals. The Brits Jack Beresford and Dick Southwood from Thames Rowing Club in Putney snubbed Hitler by winning the double sculls in the sixth final of the day after a tremendous tussle with the Germans. Then the boys in the Husky Clipper won the seventh in a humdinger race for which you needed a cigarette paper to separate Huskies from Italians and Germans at the line (women’s rowing events entered the Olympic program in 1976).

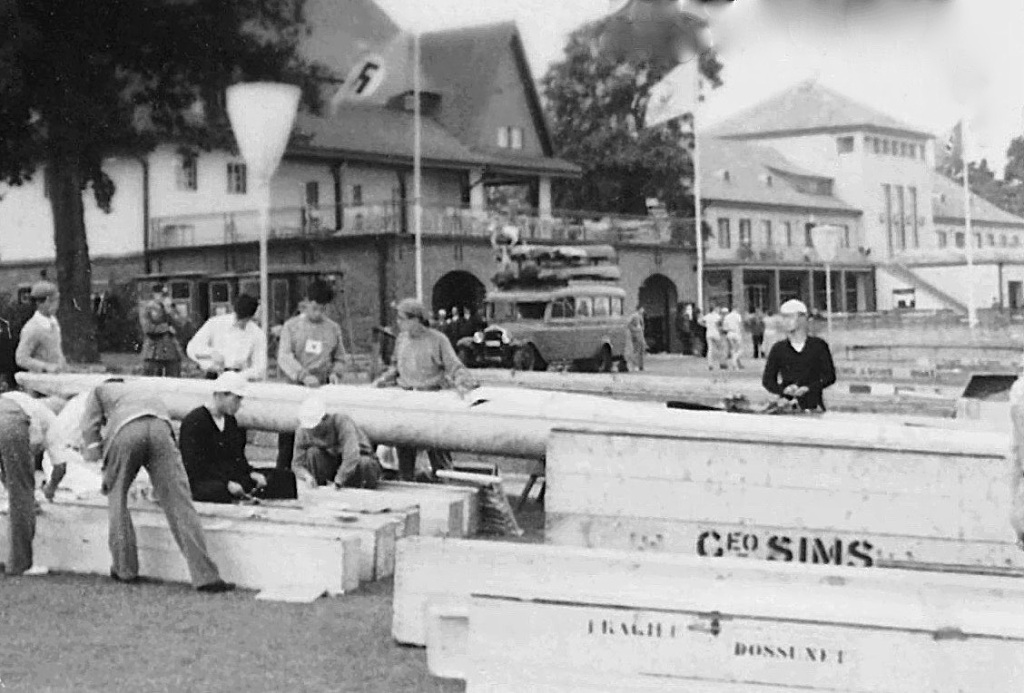

A curiosity about the British double sculling crew was that their boat was mislaid for a day or two in Hamburg’s railway marshaling yards, a mishap that deprived them of practice – although a boat was loaned to them by English professional coaches employed by the German rowing federation (Deutscher Ruderverband). Was it just a coincidence that a French four was also shunted aside? How could the German railways of all railway companies be so careless?

The Americans also suffered a mishap in Hamburg docks when the Husky Clipper, Pocock’s shell, was being unloaded. The Husky crew threaded the one-piece boat carefully down two decks of the Manhattan and secured it to slings before entrusting it to the ship’s crew. It was hoisted over the side swinging from a derrick and made contact with the ship’s rail. The impact ripped a 25-inch tear in Husky’s skin. George Pocock and Lawrence ‘Monk’ Terry, coach of the American coxed four, observed the incident from the deck above. Monk awaited an explosion from the boat builder, but after a long pause, George said quietly: ‘Those fellows need more practice unloading boats.’

The British double scullers were coached by Eric Phelps, an English sculler who was employed as chauffeur and rowing coach for the motor manufacturer Georg von Opel. Phelps was a member of a famous Putney dynasty of boat builders and professional oarsmen, and he possessed intimate knowledge of the host country’s crews.

When visiting England in the summer of 1936 Phelps did not like what he saw of Beresford and Southwood’s training and so he challenged them to race him in their double against Eric in his single. Phelps triumphed over two-men-in-a-boat on Henley Reach, and the losers agreed to hire him. Their new coach judged that their boat was a wrong fit, and a new double sculler was made by craftsmen in Putney in record time. Phelps also told them that their German opponents, Willi Kaidel and Joachim Pirsch, were ‘an 1800 metre crew’, a forecast that proved correct. In the 2000-metre final the Brits trailed the Germans until the latter ran out of puff and powered past them in the last 200 metres.

Incidentally, both doubles jumped the start. Southwood realized that Victor de Bisschop, the starter, could not see the boats under his charge once he had raised his giant megaphone to his lips. The British stroke man told Beresford to start on the ‘Etes’ of ‘Etes vous prêt’?, prior to yelling’ Partez’. The Germans made the same observation and took the same action.

The British double scullers set the scene for the bleu riband event. The American eight was dealt an extra challenge by the organisers when allotting them a slow lane (meteorologically speaking) for the final despite their leading the fastest semi-final that under the rules should have entitled them to a fast one, next door to the German boat.

Thus a pong that resembled the suspicions that had tainted the reputation of Hamburg’s railway yards hung over the waters of Grünau on 14 August 1936 when six eights lined up for the start of their final race – a race that would also conclude their lives together in the same boat.

The result defied the preferences of the officials who directed Washington to their un-rightful lane.

The winning times of the three semi-finals were:

SF1 – USA, 6.00.8.

SF2 – Hungary 6.07.1.

SF3 – Switzerland 6.08.4.

Winning times of the three repêchages were:

REP1 – Germany 6.44.8.

REP2 – Italy 6.35.6.

REP3 – Great Britain 6.29.3.

The medal winners finished within a second of each other, while only ten seconds separated the six finalists.

Final: 1

USA 6.25.4.

2 Italy 6.26.0.

3 Germany 6.26.4.

4 Great Britain 6.30.1.

5 Hungary 6.30.8.

6 Switzerland 6.35.8.

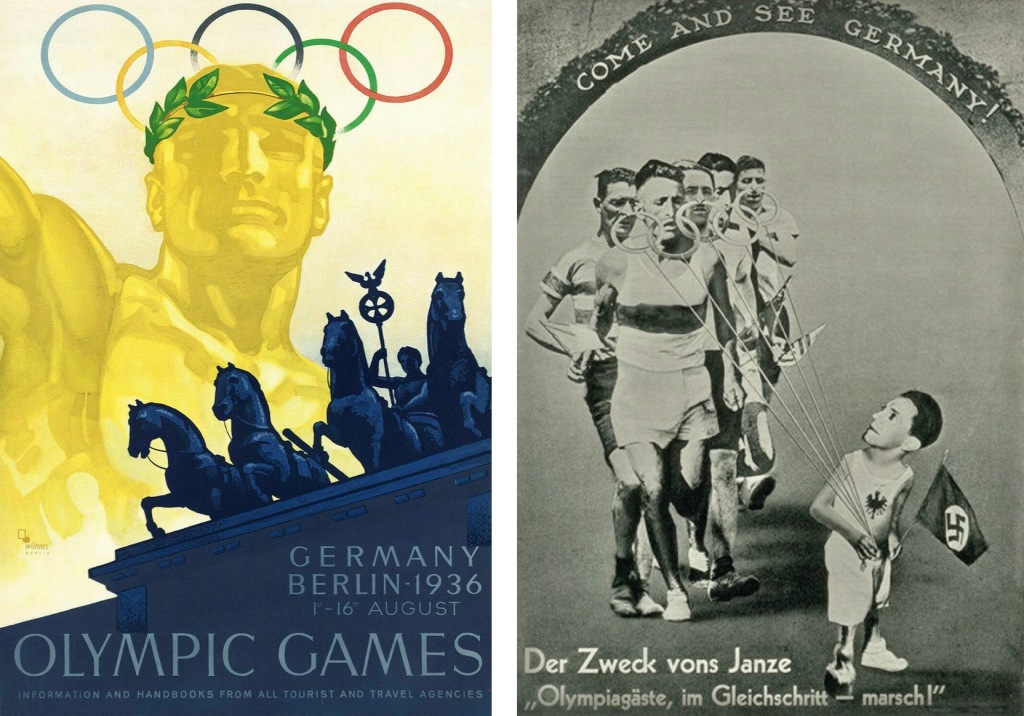

Clooney’s film gives short shrift to the politics surrounding the Games in 1936, for the good reason that he would require another couple of hours to get to grips with it. But politics there were plenty. For a start, the Olympics were awarded to Berlin in 1932, before Adolf Hitler rose to power. At first he favoured cancelling them, but later warmed to the persuasion of his acolytes that an efficient meeting would enable Germany and the National Socialist Party to gain much in the sphere of public relations, whereas cancellation may give Germany a bad name and squander a prize political conquest.

The persecution of Jews slowed but did not stop, to the extent that senior people among the games organisers who may have been tainted by Jewish connections retained their positions, at least until the party was over.

Innovations were introduced to the games, examples being live commentaries, repêchages and an opening ceremony. For the first time, the organising committee called upon the ‘Youth of the World!’ to come together (‘Ich rufe die Jugend der Welt!’).

By the way, Hitler was late arriving at the opening ceremony. The US team broke step and strolled into the stadium instead of marching, and the British eight took a stroll outside for a cigarette and released a basket of white doves. When the birds of peace were let go at the end of the ceremony, the company of 30,000 was 30 birds short.

While Berlin spruced itself up and filled with all manner of uniforms that were not all of an athletic variety, opposition to the venue grew in Europe and America as knowledge of Nazism spread. The anti-Olympic movement was particularly strong in the United States with its multi-cultural melting pot of African Americans, Jews, Germans and Anglo-Saxons, and it was particularly strong among track and field athletes. Left leaning groups in Europe began to plan an alternative games in Barcelona, but that initiative was quashed by the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, a dreadful conflict in which the republican forces of democracy took on fascism, and fascism forces aided by Hitler.

In addition to the boycott, both the depression and the destination made it very difficult to raise funds to send an American team to Berlin. The boycott was eventually defeated by a poll at the 1935 convention of the American Athletic Union. The vote was moved by Avery Brundage, a future president of the International Olympic Committee, who was a ‘truculent and arrogant anti-Semite’, according to Michael J Socolow’s book Six Minutes in Berlin that tells the story of the eight-oared final. Brundage blamed a conspiracy of Jews and Communists for the popularity of the boycott, announcing to the press that ‘certain Jews must now understand that they cannot use these Games as a weapon in their boycott against the Nazis.’ The leading instigator of the boycott was actually a Roman Catholic, Judge Jeremiah T Mahoney.

Clooney’s movie leaves no uncertainty about conditions on the farms and forests of the Northwest and its largest city, Seattle, during the depression of the 1930s. Minority groups such as the Asian Pacific Americans were subject to racism, loss of property, and failed claims for unemployment pay due to holders of American citizenship. Fuelled by Eleanor Roosevelt’s book It’s Up to the Women (1933), a movement to promote recognition of women as equal to men began during depressed Seattle. Violence during the Maritime Strike of 1934 cost Seattle much of its maritime traffic. The introduction of seven-oar Joe Rantz as an abandoned teenager living on poached salmon in a rusty farm vehicle while learning to depend on no-one but himself is truly shocking. The struggle that Rantz and his contemporary working class boys endured to earn themselves higher education is vivid.

Where the film really scores is its portrayal of rowing, the team activity par excellence, from inside the boat. None of the thespian oarsmen knew rowing when they were hired. Beginning in freezing February, they devoted five months to learn to row, and in plenty of documentaries and interviews on YouTube they describe time and again their surprise at the demands of rowing on body and soul. They emerge as much rowers as actors, full of respect for the physical side of the activity and, further, understanding that trust, commitment and teamwork are the elements that make a boat go faster. There is a thorough examination of the dependency of the stroke and 7-seat upon one another. Racing sequences put you in the boat so that you can imagine watching the neck of the man in front while aware of the man looking out for you behind.

If you have friends or relatives who don’t get the greatest team sport, a visit to a picture house will deal them conversion-by-movie. As an aside, the sport’s exception to teamwork is the single sculls, the boat for loners and nutters. For an inkling of the emotions in a boat on your own, read Hugh Matheson’s account of racing against Peter-Michael Kolbe when both had their eyes set on the Olympics, a brilliant commentary from the seat of a sculler’s pants.

The Boys in the Boat knew not how the outcome would turn when they arrived in Berlin to row in the 1936 Olympic regatta. But Daniel James Brown who wrote the book and George Clooney who filmed it know the result before they start, as do millions of readers and moviegoers. So the first challenge is how to keep the punters alert when they know how it ends. Major compromises simplified matters like, for example, contracting the Washington crew selection to one year when in fact dozens of men tried for a seat in the top crews over three or four years. Another compromise that bore no effect on the plot – the Poughkeepsie regatta in 1936 did not double up as Olympic trials as assumed in the movie. Trials took place a week or so after Poughkeepsie on Lake Mercer, near Princeton.

That August day in Berlin in 1936 brought glory to the boys aboard Husky Clipper and their coach, the Dour Dane. Their feat was a metaphor for their generation. They and thousands who had visited the German capital for one purpose or another returned whence they came. Washington’s achievement received fewer column inches than it deserved because of a newspaper strike in the US. In the Berlin streets the American response to ‘Heil Hitler!’ was ‘Heil Roosevelt!’ Three of the crew kept journals of their visit, as did several of the British oarsmen. Accounts written by competitors can be found in Regatta magazine’s editions published before the Olympics of 1988, 1992 and 1996. And a good dig-down in YouTube will come up with several documentaries and interviews of leading players in this remarkable story.

George Pocock sensed the dark side of Germany and took his American wife Frances to England to meet his relatives and take a charabanc trip to Scotland. Most of the crew graduated as engineers, and several spent a lifetime in Seattle building aircraft at Boeing – as Pocock did during the Great War, mounting seaplanes on floats like giant Eton sculling boats. The story of the Boys would have taken a very different turn if George had stayed at Boeing instead of returning to his ‘banana boat’ workshop when the Treaty of Versailles was signed.

Thanks Chris for a deep critique of the film, which explains it’s apparent shortcomings, essential to convert such a good many faceted book into an excellent 2 hour film.

The extra details about 1936, including about my father & Dick Southwood and the training of the actors, make fascinating reading.

It’s going to worth watching the film again when I believe it comes out on Amazon.

John Beresford.