22 January 2024

By Lee Corbin

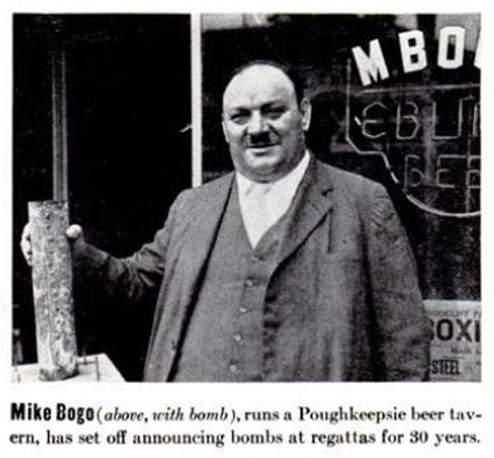

Lee Corbin writes about Mike Bogo, the Poughkeepsie Regatta “Bomber,” who got his job because he liked firecrackers.

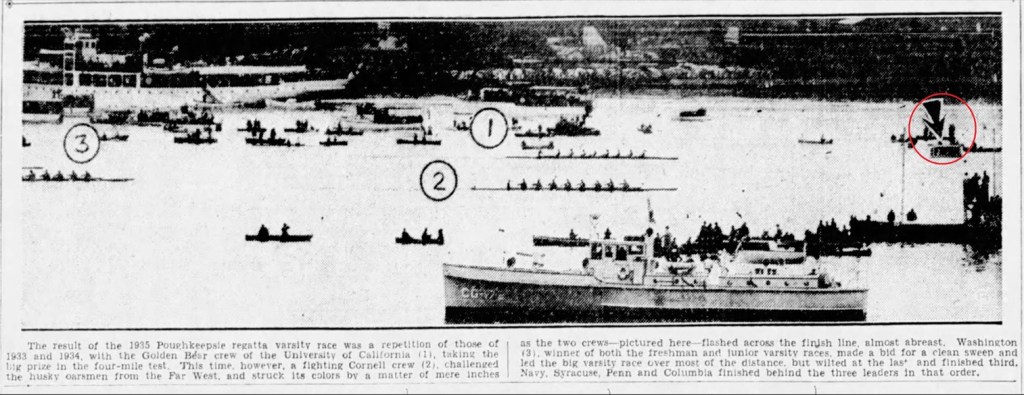

From his exclusive vantage point atop the Poughkeepsie railroad bridge, Mike Bogo watched as seven shells came swinging his way down the Hudson. It was the final race, the varsity eights, with Washington having won the earlier freshman and JV races. At the three-mile mark, as the boats passed under the bridge, the only real race was between Cornell in lane 5 and California in lane 1 with Cornell in the lead. Taking the lit cigar from his mouth, Mike touched off the fuses of five mortars, or “maroons,” to signify the leader at that point.

The races of previous years had made it almost an unwritten rule – the leader going under the railroad bridge would be the winner. The boats, now a mile away from Mike in the lengthening shadows of early evening, crossed the finish line without an obvious winner. A telegraph key installed at Bogo’s ‘bomb’ station and connected to an observer at the finish line clacked out the winner. No matter as to what message it transmitted, for Mike interpreted it as Cornell and detonated another five explosions and billowing clouds of smoke. Still believing in a New York victory Bogo displayed the red and white Cornell banner off the bridge, his secondary responsibility of a visual report. If the sound of cheering suddenly stopped in one portion of the crowd and started in another, he must not have noticed.

With that year’s work done he headed back to La Bella Napoli, his Main Street pizzeria and tavern in Poughkeepsie, leaving behind “a tidal wave of argument and confusion unparalleled in the forty-year history of this Hudson River classic.”(Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1935) It took California coach Ky Ebright two trips to the judge’s barge before being told “We don’t care how many bombs were exploded or how the flags were arranged, California and not Cornell won.”(Chicago Tribune, June 20, 1935) Newsreel footage would eventually confirm the judge’s decision. Mike would learn of his error later that night.

Born in San Georgio, Italy, in 1886, Emanuel Bocchino came to the United States alone at the age of 15 in 1902 and took up the construction trades. Settling first in Peekskill, he would move upriver to Poughkeepsie in 1905. A 1906 Poughkeepsie city directory shows he, like many immigrants in those years, had “Americanized” his name to Michael Bogo. He marries Julia Longbard, another member of Poughkeepsie’s Italian community, in the summer of 1907. The 1910 US Census has him listed as an unemployed foreman for the railroad, while Julia is shown as a ‘grocer’, most likely at the fruit stand they owned on Poughkeepsie’s Main Street.

But Mike was busy building a reputation in town as a quality mason and general contractor, who would go on to construct a number of Poughkeepsie’s public buildings, schools, churches, and utilities. If that was not enough, he and Julia eventually opened their Main Street eatery, La Bella Napoli, a beer and pizza parlor. If his church needed someone to head a committee or organize a holy day celebration, Mike would be there. And then there were the fireworks performances on Independence Day and those church celebrations, his fascination with explosives dating back to his childhood in Italy. Several articles in the mid-1930s credit him with 20 years of service to the town’s pyrotechnics, and a July 1940 Poughkeepsie Eagle News article writes that he had been supervising the town’s July 4th fireworks since 1907.

Little evidence has been found that the first four regattas, 1895 to 1898, had any system for signaling crew positions. Flags are described as being hung from the railroad bridge in 1896, but these may have been nothing more than a two- or three-mile visual aiming point for the coxswains. That all changed in 1899. “By an arrangement with Pain’s Fireworks Company the record of the positions of the crews during all the races will be signaled to the world from the west side top of the Poughkeepsie bridge.”(Brooklyn Times Union, June 23, 1899) The earliest available regatta program, dated 1899, also names the Pain Fireworks Company of Coney Island as providing the signal explosives from the railroad bridge. While not mentioned in each of the next sixteen years, there is enough newspaper coverage to assume this was the standard signaling procedure. This continues through 1916, after which the regatta was suspended through 1919 due to the war, and when reestablished in 1920 is held that first year in Ithaca’s Cayuga Lake.

From 1921 until 1926, the IRA Board of Stewards and the town’s regatta committee had a difficult time deciding on the best method of signaling where the crews were in the race and the eventual winners. For the first post-war regatta back on the Hudson a system of black and white barrels, hung in each lane at various heights, was deemed “unsatisfactory.” Explosive charges were returned in 1922. Once again in 1923 bombs are out, this time replaced with large 6’x8’ banners to replace flags “no bigger than handkerchiefs”. The following year, 1924, both flags and explosives are used for signaling positions. In 1925, bombs are once again abandoned in favor of banners. This time, however, the judge’s launch will also travel the length of the course with school flags in order of finish flying from the mast.

In a June 29, 1935, Newsweek article reporting of Mike Bogo’s unfortunate event, he’s quoted as saying he had asked Peter Troy for the job “on account of I use to like to shoot off firecrackers when I was a kid.” Peter H. Troy was a Poughkeepsie banker, stockbroker, and civic-minded citizen who joined the Poughkeepsie regatta commission in 1922 as the secretary and was elected chairman in 1925. It’s unclear when Mike became the official regatta ‘bomber,’ but shortly after Troy’s election as chairman seems to fit. “Michael Bogo Will Discharge Explosives That Will Show Which Crew Is Leader,” the June 12, 1926, edition of the Poughkeepsie Eagle News proclaimed. In 1926, the phrase “Announced by Salvo of Bombs” appears in the official regatta program as the method, along with flags, to signal crew positions. That method is used through 1939, presumably all under the hand of Mike Bogo.

Marist Archives and Special Collections

It’s June 1936, and Mike has vowed to never again repeat his blunder of the previous year. It’s the Junior Varsity race, with Navy in lane 2 and Washington in lane 5. Which boat was in the lead going under Mike’s observation post has not been determined. Navy crosses the finish line first, or so he thought, and two bombs are blasted into the sky. Coast Guard cutters, apparently not anchored anywhere near the finish line, nearly deplete the boilers of steam blowing their whistles in celebration. This time, Mike quickly recognizes his mistake and launches five bombs so quickly it appears that the shell in Lane 7 has won. Except, with only five JV boats, there is no occupant of lane 7. With Navy crossing the finish line a good 10 seconds after Washington, Mike may have just mixed up who was in those two lanes. Spectators in attendance had a good laugh at Bogo’s repeat performance, although the JV race did not cause the same “tidal wave of argument and confusion.” It was the upcoming varsity show that mattered, and Mike’s performance was flawless.

There’s an old saying that trouble comes in threes.

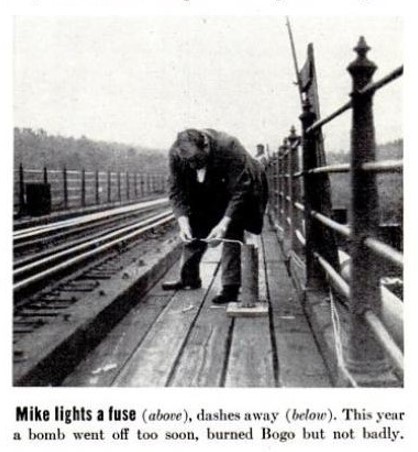

Now it’s 1937, and The Brooklyn Daily Eagle of June 19 dredges up Mike’s performance over the prior two years of the regatta. “Poughkeepsie thought the War Department was blasting a new channel.” was their comment on events of 1936. That day, it was once again the Junior Varsity race. Only three boats that year with Washington in lane 1, winning with a new course record against Navy and Cornell. With only one bomb to set off Mike touched his cigar to the fuse, a fuse that burned through to the charge almost immediately, with an explosion burning his hand and scorching his face. His injuries may not have been as serious as the initial articles reported, as there was no further mention of Mike Bogo that year. The regattas of 1938 and 1939 must have gone smoothly as Mike’s only mention those years were his being “ready to go”. His restaurant La Bella Napoli did, however, receive a glowing review as serving the best pizza in the state in October of ’39.

Fully expecting to be employed once again in 1940, Mike was surprised to learn that the chairman of the IRA Board of Stewards, Maxwell Stevenson, had decided that explosives would no longer be used to indicate the order that boats crossed the 3-mile mark and finish line. Stevenson, himself a former Columbia varsity oarsman, had rowed Poughkeepsie in 1901. Named the chairman of the stewards in 1923, it apparently took him until 1940 to learn that crews found the bomb explosions “disconcerting”. At $1.00 per bomb, paid to Mike Bogo, it was more likely to have been an economic decision. And it lasted one year. In January 1941, Stevenson resigned his position and was replaced by Capt. Thomas S. King, athletic director of the US Naval Academy. Mike was back in business.

His “disconcerting” bombings must have gone well that year, as his name did not make the newspapers until October of 1941 when health problems caught up with him. Gangrene, brought on by diabetes, necessitated the amputation of his right leg. With the cancelation of the regatta during the war years, Mike had set off his final regatta bomb. In 1947, while covering the first regatta since 1941, Seattle sportswriter Royal Brougham caught up with Mike Bogo. The regatta committee had decided the days of explosives were over, instead using pennants suspended from the bridge to indicate positions. With contempt in his voice, Mike told Royal “No more bombs! Imagine using flags that don’t make no noise. I ain’t even gonna watch the old races this year.” (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, June 18, 1947)

Mike Bogo passed away at the age of 62 on March 7, 1949, at Poughkeepsie’s Vassar hospital and is buried in Poughkeepsie’s Saint Peter’s Cemetery, along with Julia who passed away in 1966.

“You miss Mike Bogo’s big bombs, particularly for learning when the race starts.” (The Poughkeepsie Journal, June 29, 1947)