18 December 2023

By Bill Miller

Rowing historian Bill Miller is undertaking a huge project to search for 19th-centuary rowing articles published in the Boston Globe. In a two-part article, Bill will share what he has found about some of the professional oarsmen during this period.

Here is the background of the 19th century professional rowers:

The period after the Civil War brought a noticeable improvement in prosperity. Rowing races grew in popularity. It was a sport that developed from the large number of people that were employed with the oar. The public easily recognized rowing and races drew tens of thousands of spectators. The successful scullers became the first sports stars. Newspapers wrote about their every move: training, race preparation and plenty of gossip. Other professional sports were just developing.

Sources of income for the professional rowers came from cash prizes, perhaps a cut of the gambling profits for a victory (and sometimes a loss), deals for gates receipts and a cut from train tickets sold to a race site. Every opportunity to cash-in was pursued.

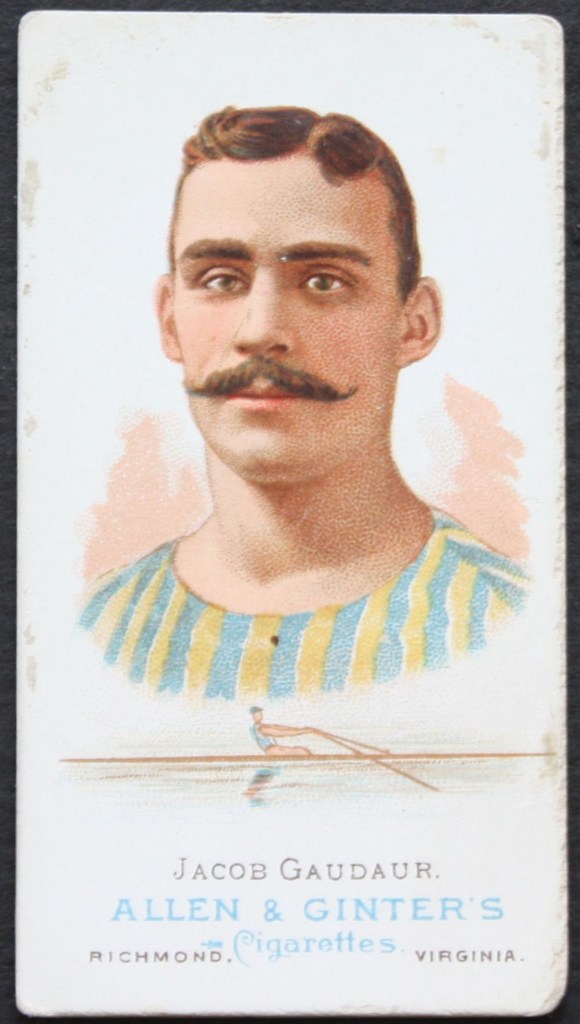

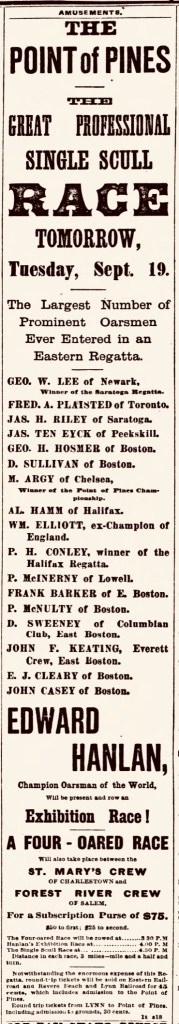

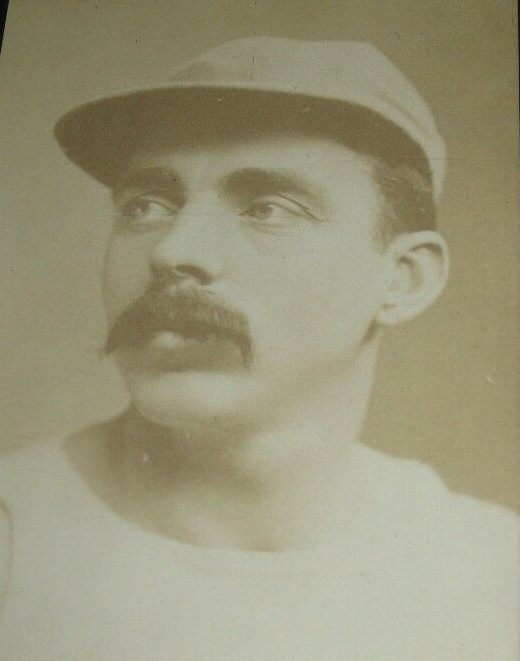

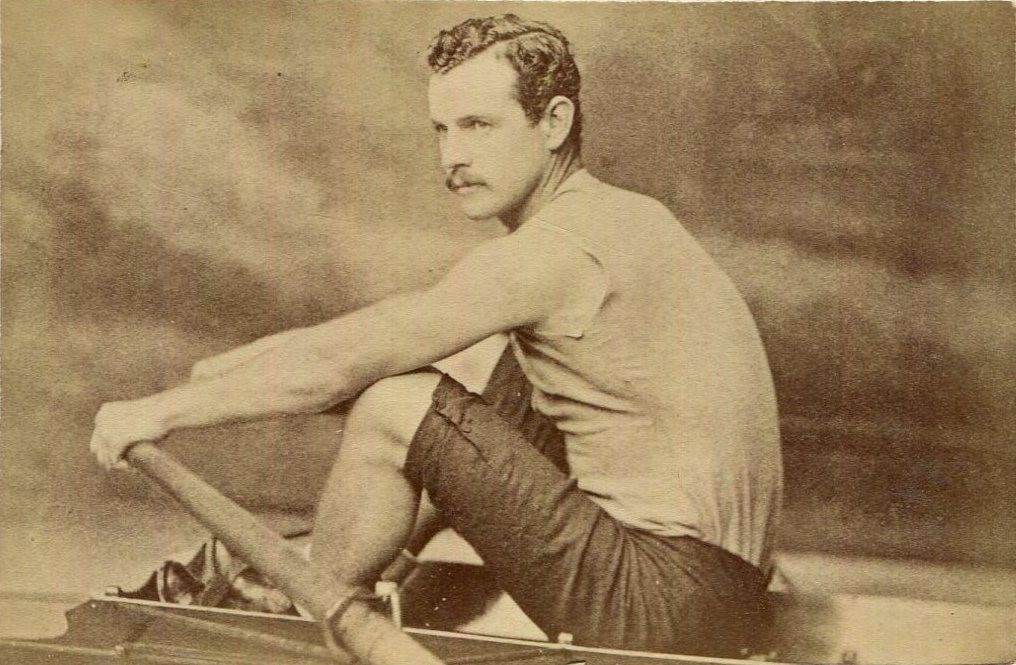

Some of the names of these 1870s-1880s stars were World Champion Edward Hanlan from Toronto, Charles Courtney from New York, Fred Plaisted originally from Maine, Jacob Gaudaur from St Louis, George Hosmer from Boston, Wallace Ross from St John, New Brunswick, John Teemer from McKeesport, Pennsylvania, John McKay and Albert Hamm from Halifax, Nova Scotia and others. Also, there were popular scullers from England and Australia who travelled internationally for racing honors and big dollars.

Some professionals attracted audiences wherever they would go. It didn’t take long for promoters to turn their popularity into profit.

Edward Hanlan became World Champion after defeating Edward Trickett from Australia in London in 1880. He attracted huge crowds wherever he raced but also drew crowds to watch his sculling demonstrations.

Their Activities:

Some would venture into other athletic events to see if they could supplement their income.

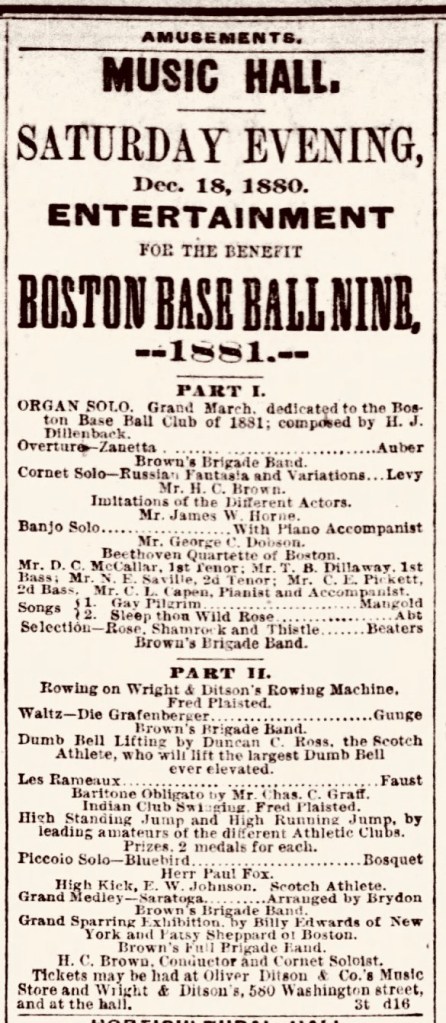

Fred Plaisted was a successful professional sculler and was well liked by the public. He had a great wit, was playful and often told embellished stories. Also, he was very adventurous. He tried boxing and pedestrianism, which was very popular in the 1880s.

Note: To convert 1880s dollars into today’s values, multiply by about 25 so $100 in 1880 is about $2,500 today.

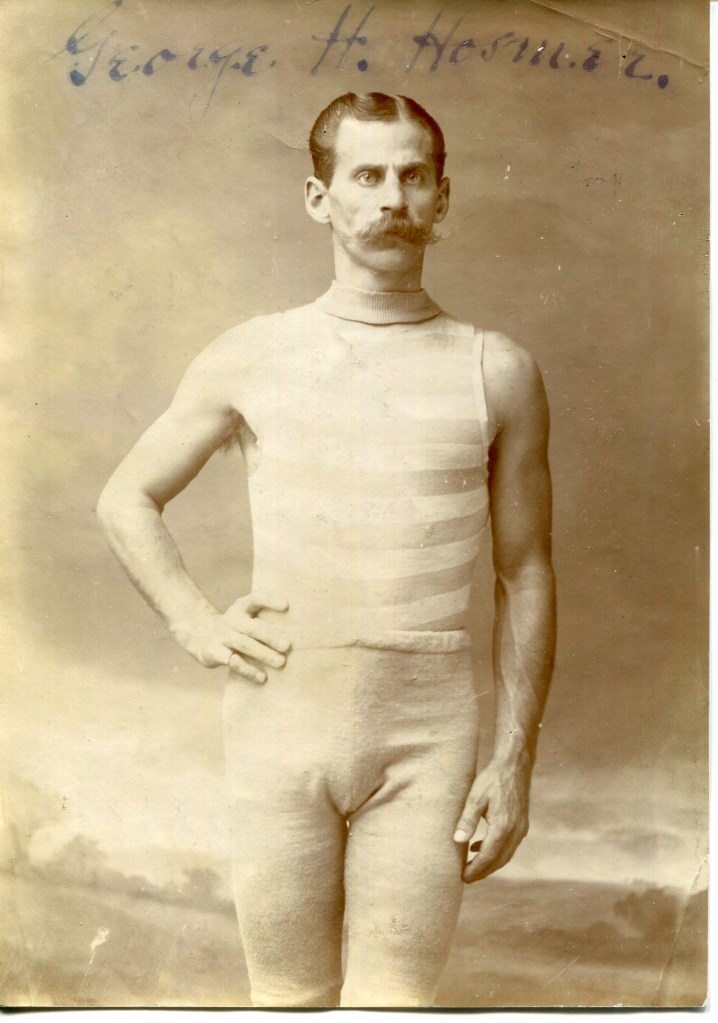

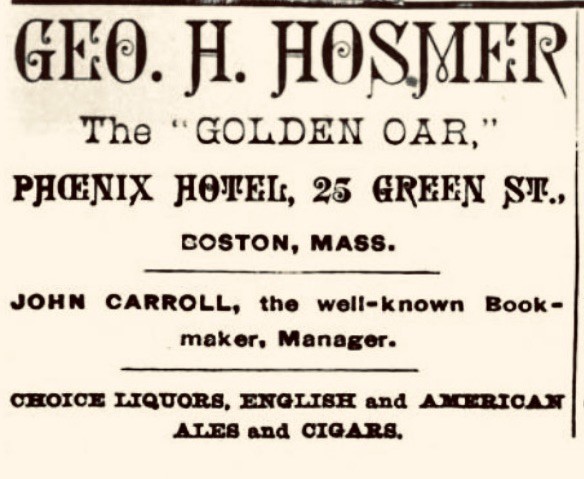

George Hosmer was another Boston favorite professional sculler. He became proprietor of The Golden Oar, a saloon on Green Street in Boston. It was the stopping spot for professional scullers, promoters and bookies.

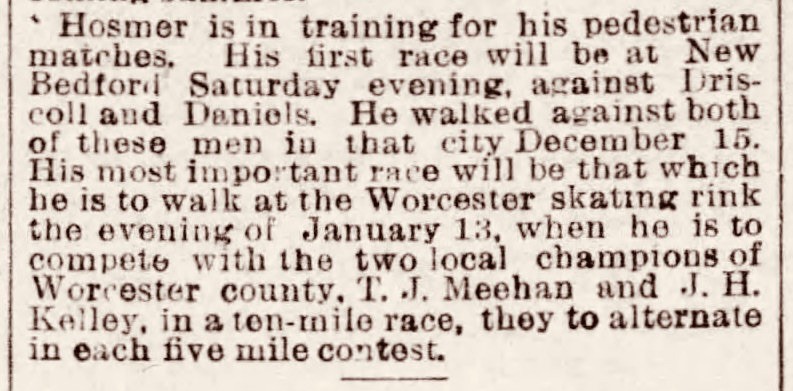

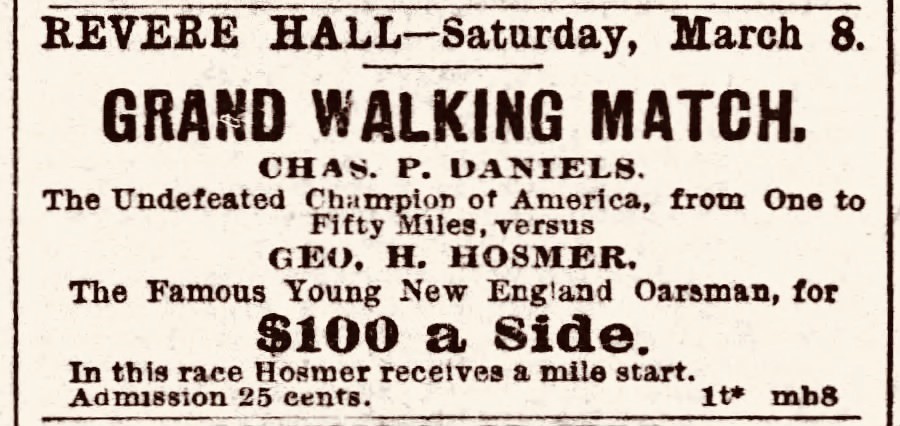

Hosmer and Frenchy Johnson tried their hand at pedestrianism.

Another off-the-water entertainment form was in halls and auditoriums. Rowing machines had been developed so the stage was a place to draw the public and produce supplemental incomes for the professionals.

And Hosmer’s exhibition.

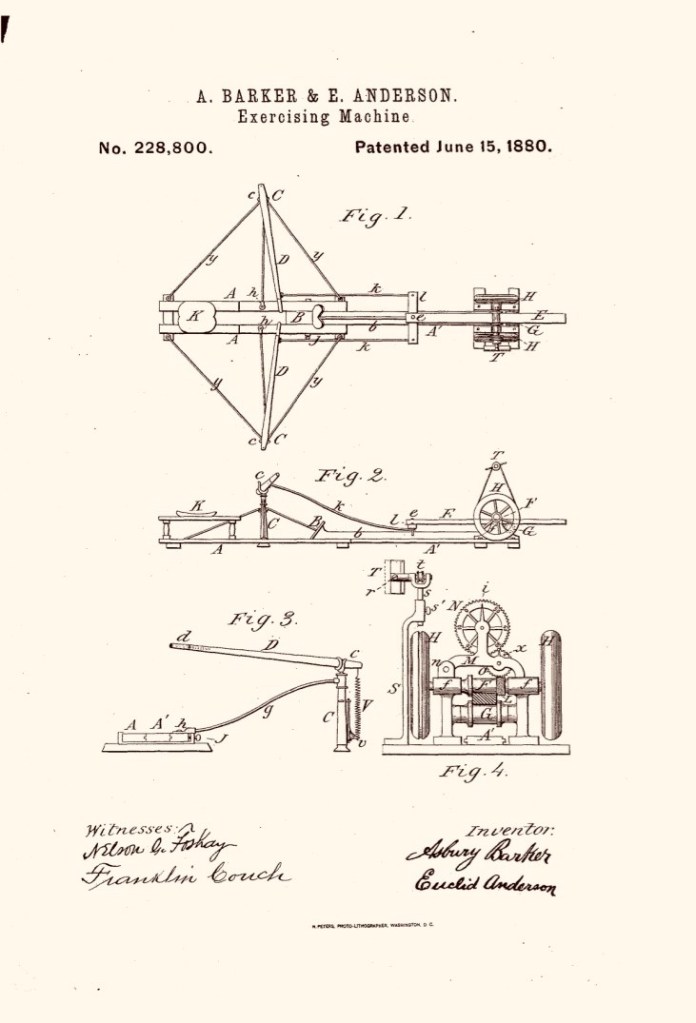

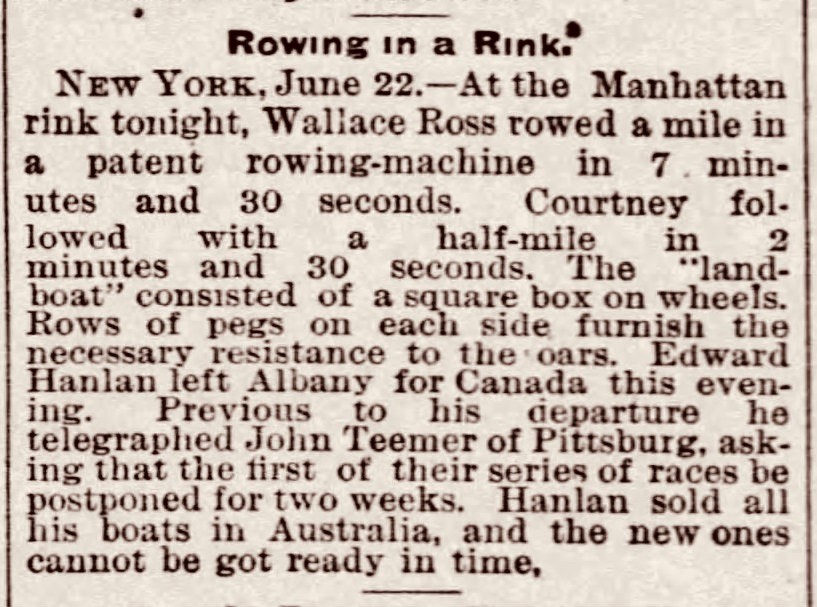

How about an indoor sculling race? William Spelman, an enterprising inventor, built a “rowing-machine”. It was a sculling trolley that ran on tracks. The sculler sat on the trolley and locked the outboard end of the sculls into pegs that ran all along both sides of the track, thus propelling the sculler along.

Wallace Ross vs Charles Courtney trolley race in New York City

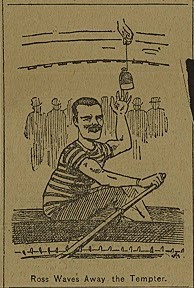

Caricatures of the Courtney vs Ross trolley race at the Manhattan Rink, 22 June 1885.

Notice the caption on the right, “Courtney’s Vision of a Saw”, referring to when he had his two shells sawn in half the night before his big race with Edward Hanlan in October 1879.

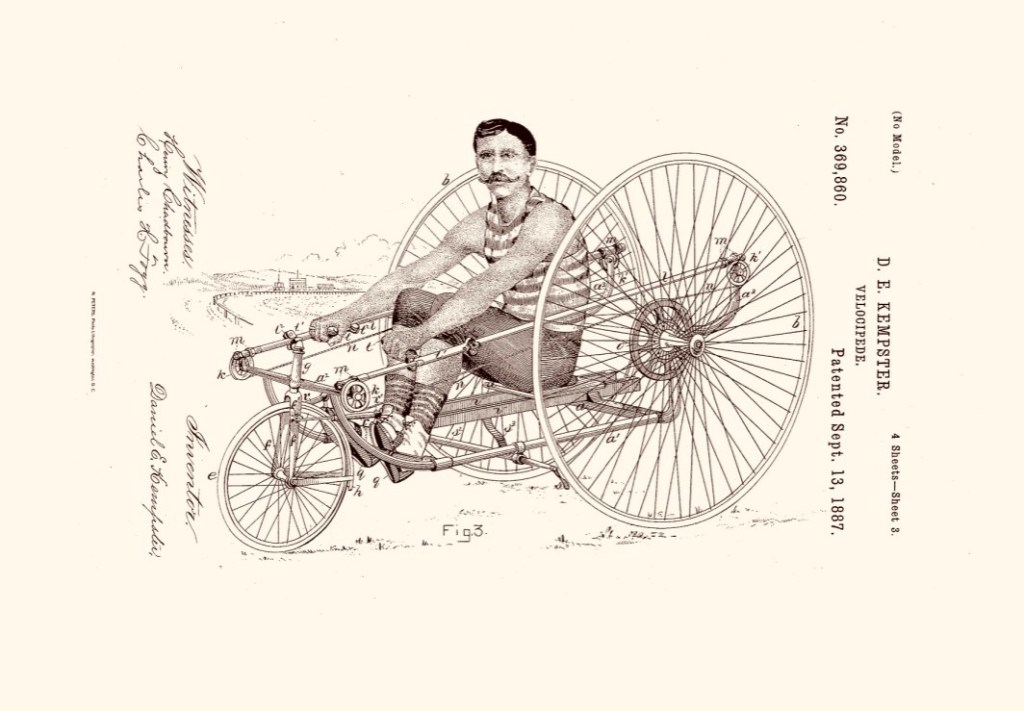

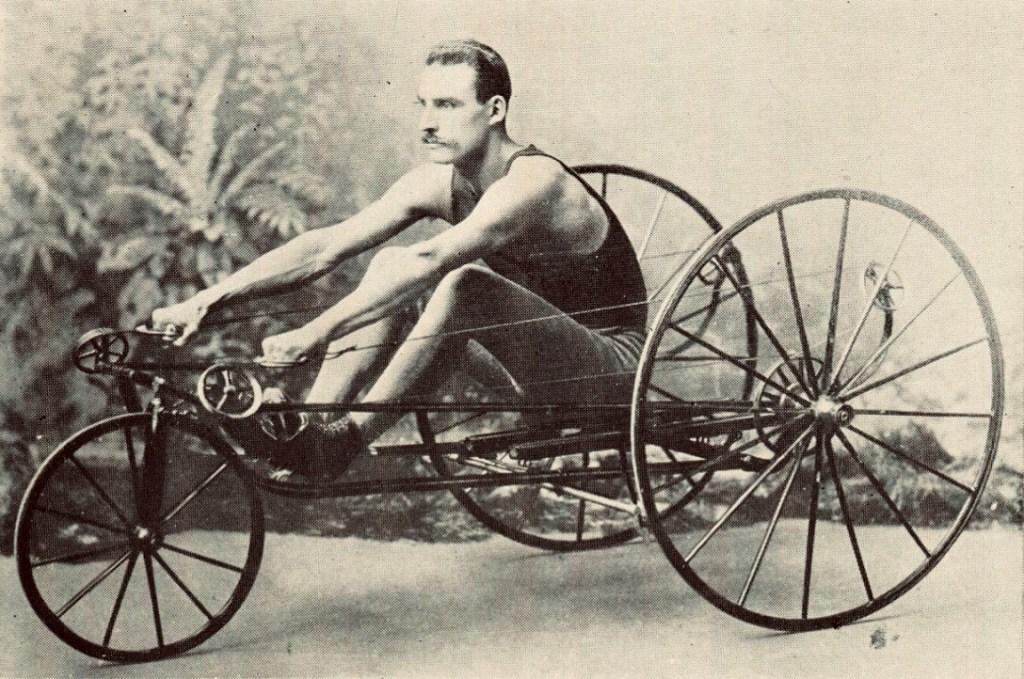

In 1884 and 1887 Daniel Kempster patented a velocipede or land rowing tricycle and called it a Road-Sculler. He married the sculling action to a tricycle apparatus.

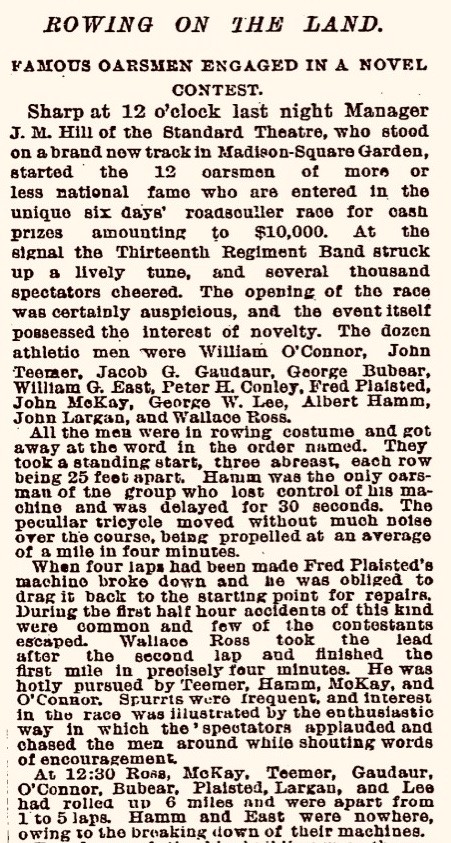

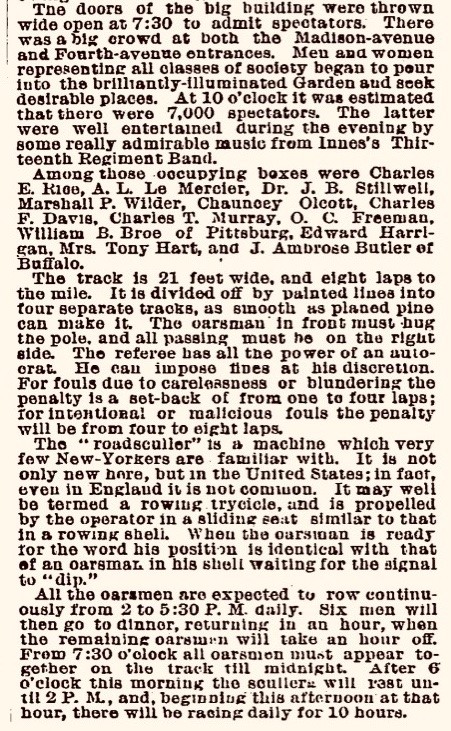

It didn’t take much encouragement for an event promoter to organize a race. The promoter was C. H. McConnell and he reserved Madison Square Garden for a six-day race. An oval wooden track was installed, eight laps to the mile. He recruited some of the best professional scullers and posted very large cash prizes totaling $10,000.

In a previous road-sculler race, Wallace Ross was the champion and was a favorite for the Madison Square Garden race.

Besides Wallace Ross, eleven other professional scullers were entered: Jake Gaudaur, Fred Plaisted, Peter Conley, John Largan, George Lee, George Bubear, Albert Hamm, John McKay, William O’Connor, John Teemer and William East.

The race started on October 8th. Seven thousand spectators saw the start at midnight. The scullers raced from 12:00 AM until 6:00 AM. Then started again at 2:00 PM racing to midnight. There was only a one-hour break in the evening for dinner, creating a pretty grueling schedule for six days.

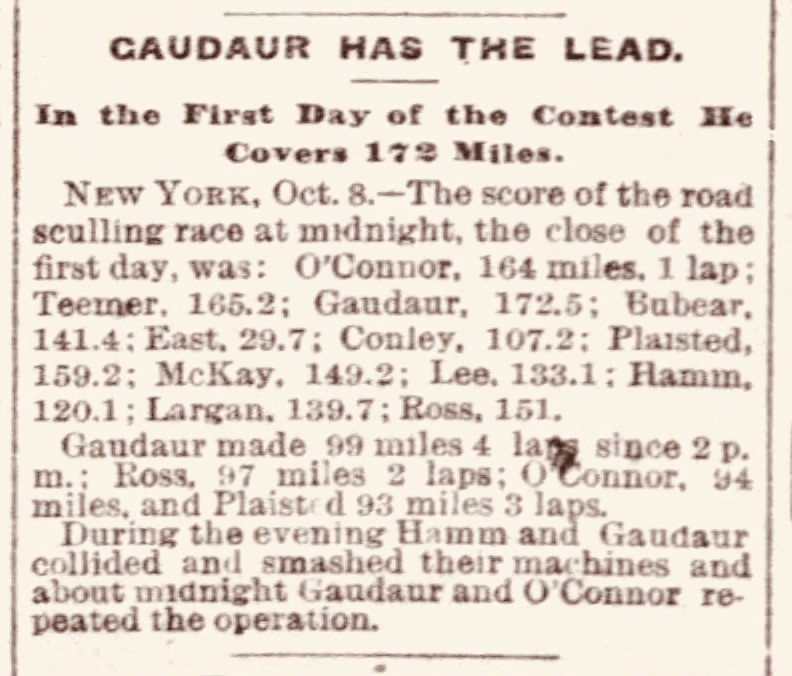

During the first day accidents and equipment failure delayed some of the competitors. Only a few had ever used the machine and controlling it at full speed was a challenge. Also, the machines weren’t engineered for the professionals’ high performance so there were equipment breakdowns.

After the first day the scullers broke out gloves and seat pads to help fight ailments. They averaged between 12 and 13 miles per hour for their daily nine-hour shift.

At the end of the first day, Jake Gaudaur led with 172.5 miles.

Following the first two days, the scullers were pretty well trashed. Teemer and O’Connor couldn’t answer the call to the starting line at 2:00 PM and dropped out. Teemer’s hands were covered with blisters and O’Connor’s muscles were aching to the extent that walking was challenging.

The racing hours were reduced so that the scullers could make it through the six days of racing. The afternoon starting time was changed to 4:00 PM instead of 2:00 PM and a longer rest break was scheduled in the evening.

On the fifth day Lee and Largan couldn’t make the afternoon start because they were physically “disabled”. It was a grueling event.

After Day-5, Gaudaur accumulated 419 miles.

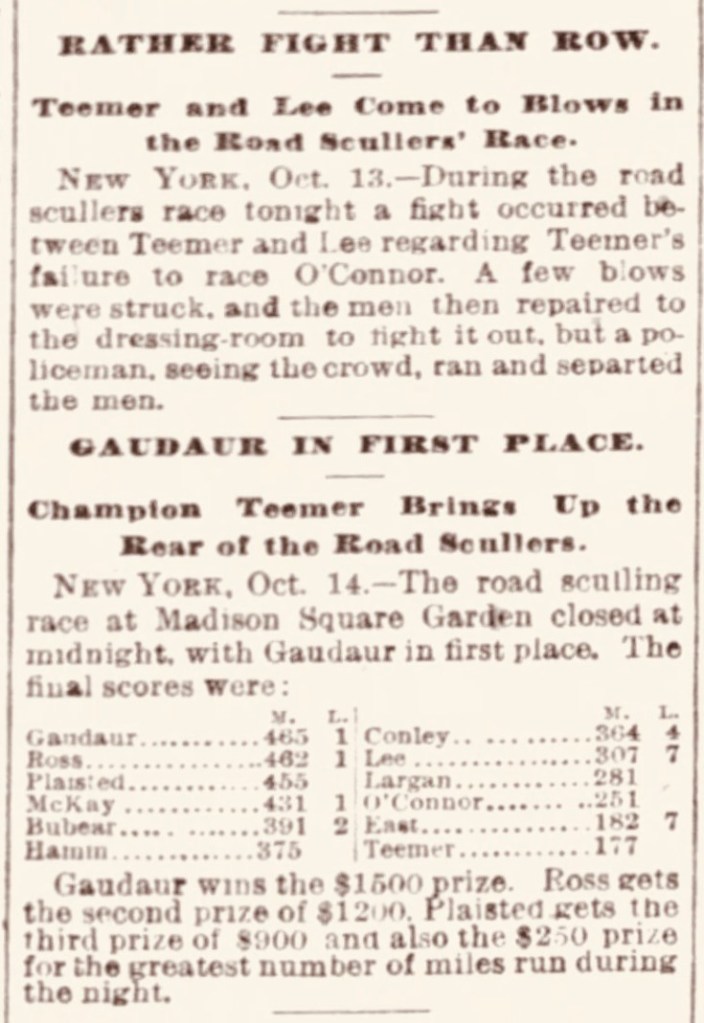

Completing Day-6, Jake Gaudaur won $1,500 and the favored, Wallace Ross, placed 2nd. He collected $1,200. However, just before the finish there was an altercation on the track between Teemer and Lee with “a few blows being struck”.

So, as the above shows, the professionals were also very active off the water.

Part II will be published tomorrow, on how George Hosmer became an actor.