15 December 2023

By Lee Corbin

So, who built the now famous Husky Clipper? Well, George Pocock, of course, but he had a little help from several others, Lee Corbin writes.

It would be an informal christening, without much ceremony, as the new shell was funded by the university rather than being a gift. Coxswain Bob Moch asked George Pocock to do the honors as the crew supported the boat on the sloping ramp outside of the shell house. Positive it would be rowing in Berlin that summer, George decided sauerkraut juice would make his newest creation feel right at home once there:

I christen thee Husky Clipper, and like the ancient Clippers, may your bow never be headed. With this bottle of sauerkraut juice, the effervescent sap of the noble cabbage, I wish thee all the luck—On to Berlin.

And with that, the most famous of Pocock shells was born.

If George Pocock had envisioned working by himself in a lonely loft workshop, crafting racing shells for the University of Washington with an occasional boat for the California crews, those thoughts were about to end. The University of Washington varsity crew had just claimed victory for the first time at the Intercollegiate Rowing Association Poughkeepsie Regatta, and the Eastern schools took notice. Not only of the West Coast school pulling the oars, but also the shells coming out of a former WWI Navy seaplane hangar on that university’s campus.

The orders started coming in late that summer and early autumn. While still in the airplane construction business with Boeing, George Pocock had moved into a workshop at the UW boathouse in November of 1922. George’s brother and boatbuilding partner, Richard “Dick”, was now back East building shells for Yale. What had been a solo operation would soon require an assembly line workforce. By October 7, 1923, the Seattle-Post Intelligencer reported George had orders from six different schools for eight shells. Two for Harvard, one each for Wisconsin, Annapolis, California, and Groton, the Massachusetts prep school. Finally, two for the University of Washington. Columbia had a Pocock shell delivered the final week of March 1924, so their order must have been added shortly after this story was published. That same Seattle P. I. article went on to report Pocock had “put three men on his pay roll.” After nearly six years at Boeing, working with some of the finest wood craftsmen in the Pacific Northwest, George would draw on that experience when he went looking for apprentice shell builders. Charles Turner, Malcolm W. MacNaught, and Hilmar Lee would be his first employees, but who was there in 1936 when that year’s varsity shell was constructed?

In early 1936 George Pocock had orders for at least three shells, all “Eights”. The James Bay Athletic Association of Victoria, British Columbia, had a boat finishing up the second week of March. Ky Ebright, crew coach of the University of California, had placed an order on February 11 and took delivery towards the end of March. The annual UW varsity boat, contracted to be built by George, would emerge from his shop in early April. In addition to these shells, crafting the oars to row them was also required. By 1936, the Pocock shop had become a shell factory, with operations on two levels, including the loft area above the crew shower and locker rooms, allowing assembly line construction of multiple boats at the same time. At least two of his original employees, now skilled shell builders, were still with him.

Charles Turner

When the Pocock brothers left England to find their fortune, they arrived in Vancouver, British Columbia, in March of 1911. Before leaving the following year to work at the University of Washington, the Pococks had earned a reputation for quality boat building among the Vancouver and Victoria rowing clubs. Canada-bound shells would come out of Pocock’s shop for years to come, with George traveling to Vancouver several times a year. These early years in Vancouver introduced George to one of his first, and longest, employees.

British Columbia seemed to attract English expatriates. A fellow Englishman named Charles Turner from Leeds, Yorkshire, and a year senior to George, had arrived in Vancouver in 1909. Census records list his occupation as farmer. Enlisting in February 1916, Turner would serve with the Canadian Expeditionary Force in the 12th Canadian Railway Troops during WWI in France. Included in his military service records, as was standard military procedure, was a copy of Turner’s Last Will and Testament. Dated October 1917, it left everything to his mother. A revised will, dated January 1919, and revoking all previous wills left all of Turner’s possessions to a “G. Y. Pocock” of University Station, Seattle, Washington. What prompted this change is unknown, although Turner’s military payroll record may have a hint. Throughout the war, Turner’s paycheck had gone to his mother. That came to an end the same month the new will was executed. Obviously Pocock and Turner knew each other, perhaps as far back as 1911. The question remains, under what circumstances and for how long?

About six months before George would leave Boeing and return to shell building, Charles Turner stepped off the SS Princess Victoria in Seattle on June 13, 1922. Boeing documentation shows Turner was an employee but, unfortunately, not his dates of employment. His petition for naturalization was filed in October 1928, and witnessed by “G. Y. Pocock” and “M. MacNaught”, both of whom declared they had known Charles Turner since October 23, 1923. Turner certainly knew Pocock prior to that date, as would MacNaught, if Turner had worked for Pocock at Boeing. As the petition itself is dated exactly five years and one day later, those dates may have been nothing more than an administrative formality.

According to a Sunset Magazine article of December 1925, Turner’s job description “…focuses on gears, sliding seats, and stretcher boots…” of shell production. In later years, he appears to work primarily on Pocock’s increased production of oars. Turner would be employed by Pocock until age and infirmary prevented his working and would pass away in a Seattle nursing home in May of 1969 at the age of 79. His death certificate listed his occupation as a retired boat builder, and “Pocock Boats” as his employer.

Malcolm Woodford MacNaught

“The best boat builder I ever knew.” That was George Pocock’s summation of Malcolm W. MacNaught, Jr., the youngest of George’s first employees at the shell house. Born in 1902 in Bristol, Rhode Island, he was the son of a Scotland-born insurance underwriter, a ‘marine surveyor’ according to census records. His father, Malcolm Sr., had been a boat builder in Bristol until declaring bankruptcy in 1908. After about ten years in Connecticut, the MacNaughts came to Seattle around 1919, with Malcolm graduating from West Seattle High School the summer of 1922. He would marry that same year in October to Suzanne “Brownie” Chesnut, a marriage which would last about five years. While there is documented evidence of his employment at Boeing, no hiring and ending dates are recorded. He probably turned 21 years of age about the same time George hired him and may have worked building shells for about a dozen years. The 1920 Seattle city directory list his occupation as ‘mechanic’, while later editions show ‘boatbuilder’ until 1935. His name disappears from Seattle records after 1935 and is not found again until June of 1937 with a record of his marriage, in Nashua, New Hampshire, to a West Seattle woman named Corinne B. Kuehn. They would live in Malcolm’s native Rhode Island for the remainder of their lives, but would return to Puget Sound after passing away. Both are now buried in Seattle’s Forest Lawn Cemetery, Malcolm passing away in 1991 and Corinne in 2004.

Did Malcolm MacNaught participate in the construction of the Husky Clipper? Possibly. The lack of records of his residence from 1936 until the summer of 1937, during which time the Clipper was being built, would make it difficult to say with any certainty. His father does show up in a special 1935 Rhode Island census, but not the younger Malcolm. With his engagement to Corinne, it is possible he remained in the Puget Sound area until shortly before his marriage back in New Hampshire. As for Corinne herself, the Seattle city directory does list a Corinne B. Kuehn through 1937 before her name disappears.

Hilmar Lee

If ever George had a “right hand man” over the years, it would have to be Hilmar Lee. Twenty years senior to George, Hilmar Lee had already lived a full lifetime of adventure when he was in his late 30s and went to work at Boeing.

Born in Norway in the Autumn of 1871, Hilmar and two of his brothers left home for British Columbia in 1889 and took up the fishing trade. A year later, at the age of 19, he signed on with the sealing ship Annie E. Paint out of Victoria for a nine-month hunt. After a second such voyage, Hilmar returned to the fishing business on the Fraser with his brother at New Westminster. It was the early 1890s, when the run was so bountiful you could catch two thousand salmon a day. In 1896, Hilmar would be caught up in the lure of Yukon gold. He and three of his brothers headed north, prospecting and laying out the town of Candle, Alaska. Like many a smart businessman, Hilmar saw more profit in supporting the miners rather than prospecting. In 1898, he came to Seattle and purchased a square-rigger, which he loaded with a thousand tons of coal and set off for Kotzebue Sound. On a second voyage he took enough lumber to Seward to open a lumberyard. That would last for about a year, before he returned to Candle and prospecting. With three partners, they worked a 20-acre claim which eventually yielded $300,000. Altogether he spent fourteen years in Candle before coming to Seattle late in 1916. It would be one of George Pocock’s newspaper want-ads that would bring Hilmar to the Boeing Airplane Company.

Years later in his memoirs, George would write about first meeting Hilmar:

In the very early days at Boeing’s the foreman of a department was responsible for the ruling of his workmen. I used to put an advertisement in The Seattle Times Sunday edition suitably worded for the work skills required. One Monday morning a big, strong looking fellow answered the ad. He had on a big black felt hat, similar to ones I had seen on Alaskans in Seattle for the winter. Sure enough, he was from Nome, Alaska, and had built his own boat for freighting supplies from Nome to Kotzebue Sound. He had a photograph of it. He came to work and was with me for five years at Boeing’s and then with me in shell-building for 35 years.

During WWII, George would reconnect with his Boeing roots and manufacture aircraft parts as a ‘war industries’ subcontractor. He and his team constructed such items as holding brackets for crew ‘walkaround’ oxygen bottles, and floorboards for the B-17 tail gunner position using an ingenious jig designed by Hilmar.

Hilmar, like Charles Turner, stayed with Pocock for the remainder of his working life. In photos of George at work in his shop, Hilmar can often be seen in the background attending to some phase of shell construction. The 1925 Sunset Magazine article mentioned earlier writes that Hilmar Lee “specializes in hulls”. Other than Pocock himself, Hilmar probably played the biggest part in the creation of Husky Clipper. It should be kept in mind, however, it was just another nameless shell in March of 1936. Crafted with great care as they all were, but just another Pocock shell.

Hilmar passed away May 6, 1962, and is buried in Seattle’s Evergreen-Washeli Cemetery along with his wife, Jessie.

The Huckle Brothers

By 1924, as even more shell orders rolled in, it was obvious that additional shop help was needed. And who better to hire than your brothers-in-law?

One of Bill Boeing’s first employees, Myron Huckle was hired in the summer of 1916 to sweep out Boeing’s Moran Shipyard building. And Myron had a sister, Frances. One weekend he went to the airplane factory and asked Frances if she wanted to tag along. George, who was by then the foreman of the aircraft assembly department, was also there that day and they happened to cross paths. As George would claim for the remainder of his life, it was “love at first sight”. On August 31, 1922, George Y. Pocock married Frances M. Huckle, and set in motion the family affair his future workforce would become.

Along with an older sister, Beatrice, and her brother Myron, Frances also had two other brothers, George and Donald.

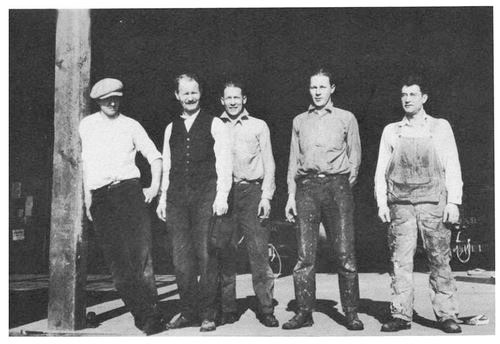

George Huckle was 19 and Donald 17 when they became brothers-in-law of George and Dick Pocock. George Huckle was a Boeing employee prior to moving to the Shell House, but no evidence of Donald having worked at the Boeing factory has been found. Whether George and Donald joined the George Pocock Racing Shells company at the same time is unknown, but they are pictured together in a 1924 shell shop crew photo.

Sunset Magazine in December 1925 described George Huckle’s specialty as “rigging, iron work, and steel tubes”, and he can be seen in several photos either manufacturing or installing oar locks and riggers.

How long George Huckle worked for George Pocock is unknown. Huckle’s WWII Draft Registration lists Pocock as his employer in February 1942, but Huckle is shown living in California during the 1950 census. Shell building appears to have appealed to brother Don, as he was still working for George as late as 1952.

Melvin Eugene Graham

Another family connection. On February 25, 1925, Don Huckle married Gladys Estelle Graham. Gladys had a brother, Melvin “Mel”, who was twelve years younger than her and would graduate from West Seattle High School in June 1935. Don may have convinced his new brother-in-law that he should consider shell building as an occupation. He certainly could have been, yet there is no proof that he was there at the shell house in the Spring of ’36. The earliest documented evidence of his employment is a February 1937 Seattle Times article. From newsreel video footage oar manufacturing, a big part of George’s business, seems to have been Mel’s specialty. Another long-time employee, he is pictured in a 1952 article along with Hilmar Lee and Don Huckle.

John Henry Clemmer

John Henry Clemmer is somewhat of a mystery. Born in Spokane in early 1912, he came to Seattle in 1932. Only one newspaper reference to his being an employee of George Pocock has been found and that was not until 1946, ten years after the Husky Clipper has been built. The 1938 Seattle City Directory does list a John C. Clemmer, occupation boat builder, residing just to the north of the UW campus. His WWII Draft Registration card, dated October 1940, lists his employer as George Pocock of University Station, and the 1940 census also shows him working as a boat builder. He would see service during WWII with the Army engineers in Africa, France, and Germany, and resumed working for George Pocock after the war. While possible, the evidence has yet to be found that Clemmer was there to work on the Husky Clipper.

The “Clipper,” Just Another Shell

What of the Husky Clipper itself? Today, it hangs in the Conibear Shell House on the UW campus waterfront, admired by many, particularly by those who make the pilgrimage to the Shell House. But the sentimentality towards the Clipper grew slowly. With George Pocock producing a new shell each year for the university, the Husky Clipper joined the other shells in the ever-burgeoning collection of boats at the ASUW Shell House. The following year it would carry the freshman crew to their share of a ‘sweep’ of the Hudson, as the UW Varsity, JV, and freshman crew won the IRA at Poughkeepsie. Not until 1946 would Clipper be mentioned in the local newspapers, when it would be rowed again by the reunited oarsmen made famous at Berlin. The next day, the University of British Columbia crew would row it in the Lake Washington International Regatta. Other than a nighttime appearance at the January ‘47 Varsity Boat Club dance, Clipper did not make the news again until 1959 when Green Lake’s Junior Rowing Commission would receive Husky Clipper as a gift in late February to help promote the sport of rowing to Seattle’s high school youth.

In the Fall of ’63, the University of Puget Sound and Pacific Lutheran University would form a joint rowing program on American Lake. Coached by former UW rower Paul Meyer, they approached the Junior Rowing Commission for a couple of eight-oared boat donations. Generously, the organization came through with Husky Clipper and one additional shell. American Lake, being adjacent to the Army’s Fort Lewis, gave Coach Meyer the idea for a unique US Army crew team. In the Spring of 1964, about the time the UPS and PLU teams were coming together, Meyer made such an offer to Fort Lewis. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that an Army crew was ever created.

In 1967, one man, the manager of the UW’s Husky Union Building (HUB) named Steven Nord, suggested the first official hint of recognition to the historical importance of the Husky Clipper. Wanting a focal point of university history, he requested of PLU that the Husky Clipper be returned for display in the HUB’s “Husky Den” food court. PLU graciously responded, and on September 9, 1967, the Clipper was ceremonially suspended from the Husky Den overhead. It would remain there until 1975 when the HUB was remodeled and moved to the Conibear Shell House. Other than a temporary stay at the Pocock Rowing Center around 2004 while Conibear was being remodeled, it remains there today.

My thanks to Al Mackenzie of the Pocock Rowing Center for his assistance in obtaining several of these photos.