23 October 2023

By Chris Dodd

The death of Thor Nilsen on his 92nd birthday on 5 October ends a remarkable period of growth in rowing brought about by swaddling the sport in fair competition, shared information and enviable management. Nilsen, a teenager in his native Norway during the Nazi occupation, had little formal education before feeding books to his enquiring mind and discoursing with experts in his interests. He took up the oar in Bærum as soon as occupation restrictions were lifted, and quickly progressed to the highest level that Norway could reach at the time. He was passionate about other sports, particularly those involving skis, but his son Steve recited to me the order of preferences:

‘1 rowing, 2 rowing, 3 rowing. Cross-country skiing was a distant 4, and 5 was speed skating.’ The common denominators are strength and endurance. ‘Both fit well with Thor’s credo in life,’ Steve said. ‘In Norwegian it is “ensam är stark,” which translates as “he who stands alone stands strong”. When committed to an idea or goal, my father yielded to no-one or nothing.’

Thor was born in 1931 to Leif Sverre Nilsen and Karen Johanne (née Nygård). His mother was brought up on a farm and went into domestic service after learning to cook. His father, who lost a leg in a train accident when he was aged 10, tried his hand at basket making before joining the family stone hauling business. Leif Nilsen’s politics oscillated between anarchism, communism, socialism and agitation, and he was involved in organising unions and cooperatives.

During the wartime occupation, the Nilsens listened to clandestine broadcasts and produced underground newspapers for the Resistance. Their son delivered the stencilled sheets on his bike. Bærum, on the west side of Oslofjord, has hills, orchards, forests and lakes surrounding mount Kolsås. Four rivers flow to its craggy coastline, and it was a pleasant place in which to grow up. If challenged, his defence was that he came across the newssheets by chance. He was never challenged, but another crime got him into trouble. He and a schoolmate broke into an airfield used by the Germans as a store for military equipment. They nicked helmets, masks, a mortar and a landmine, and exploded the mine near their school. Fortunately, Thor said, the Norwegian police were relaxed about it.

His first career as an apprentice to a printer began when he left school at 14. Later he mastered the art of silk screening. He found that he had a good head for business, but took a wrong turn when some dodgy colleagues decided to raise capital by robbery. Thor and an associate brandished unloaded weapons in the Stabekk post office and zoomed off in their getaway car. The getaway driver then grassed to his brother who was in the police, and the champion oarsman confessed immediately. Thor’s case was confused by his alleged role as a Soviet spy, a puzzling complication that he never got to grips with. ‘They tried to break me down, but it’s difficult if you don’t know what you are supposed to confess,’ he said. When appointed as the gaol’s librarian he was able to study philosophy and practice management skills. He tutored fellow prisoners in literacy and tackling their social problems. His two-and-a-half-year sentence for the robbery was reduced by a year for good behaviour.

The sentence came to him initially as both shock and setback, but it also presented Thor with lessons that would serve his future well, like not to play poker with people you don’t know. He learned to think flexibly. ‘You meet people with problems who had a bad start in life, and the message is that “you have to take responsibility for breaking the law”. But some were born on the wrong side of the law and will never get to the right side. So you learn to be flexible. Not soft, but flexible.’ The term ‘flexible’ he chose carefully. He used it to assure rowers that he had not gone soft.

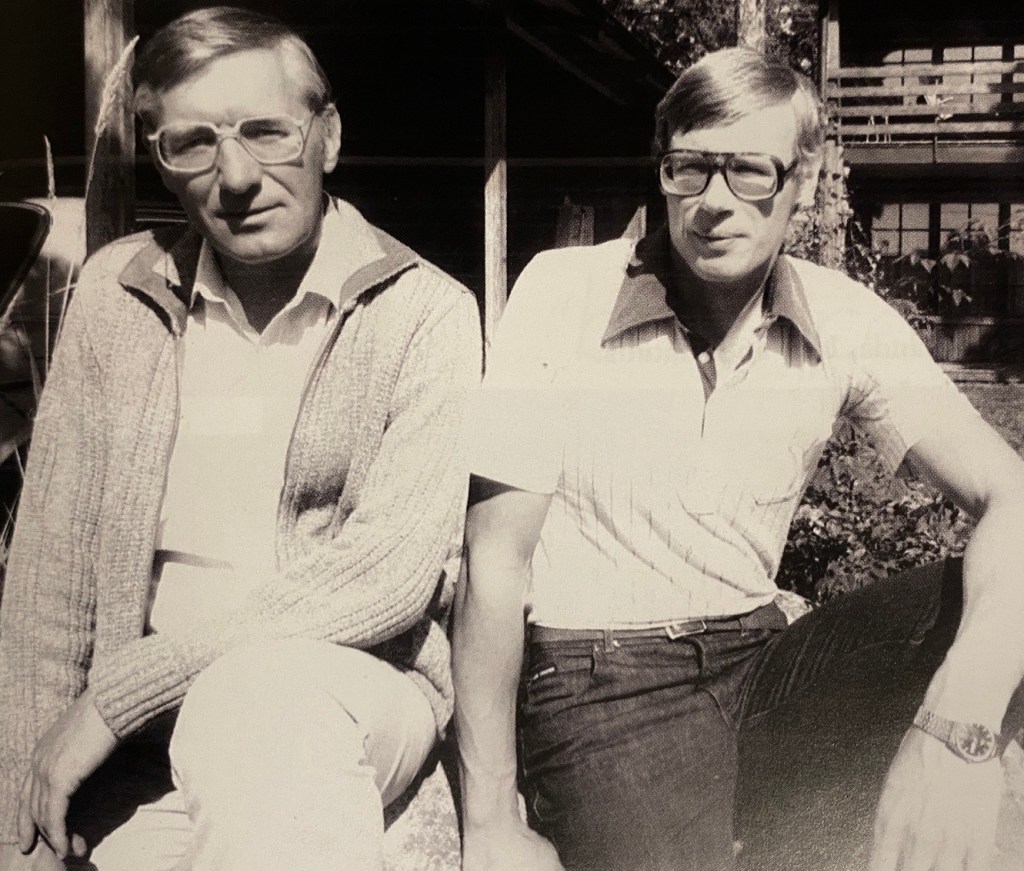

Thor represented Norway in the European Championships as a 17-year-old and in the Olympics in Helsinki in 1952, when he was 20. After Helsinki he moved into coaching and took the brothers Alf and Frank Hansen to a gold medal at the 1976 Olympics. By then he had possessed an international reputation for sharing knowledge and information in a sport that didn’t.

Rowing in Europe carried on its pre-war ways for at least thirty years after the Second World War. It was a summer sport taught largely by wisdom handed down from coach to coach. Clubs kept their ideas close to their chests, and demanded loyalty from their members, so that selection for national teams was usually restricted to ready-formed units that were only as strong as their weakest man or woman. A national squad was unheard of in countries where the bedrock of rowing lay in universities, colleges and eight-oared boats. Talented individuals and small units thus seldom had little chance of representing their country,

Rowing technique in Norway was largely influenced by English coaches, or in the case of Steve Fairbairn, an Australian resident in England. The English ‘orthodox’ stroke was originated by men who worked with oars as ferrymen, fishermen, firemen, boat builders, life savers, pilots, shipwrights, ship-to-shore traders, sailors and those who pulled passengers in water taxis. The nineteenth century amateurs who went rowing for recreation learned their skills from these sons of toil. So Thor fed his curiosity on what he saw and heard at regattas and boathouses. His quest to find out how to make the boat go faster was open-minded and led him to consult experts in many disciplines.

The double-sculling Hansen brothers came under Nilsen’s influence in the early 1960s. Together with the four that he formed at Bærum, they struck gold at the 1975 World Championships at Nottingham at a period when East Germany, the Soviet Union and other eastern Europeans dominated medal tables. Crews apart, three men helped Thor to take Norway into their company. These were Ivan Vanier, a Dutch Indonesian who was a sculling genius, Professor Per-Olof Åstrand of Sweden’s Royal Gymnastic Central Institute, a founding father of exercise physiology, and Professor Kåre Rodahl of the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences. Åstrand and Rodahl pioneered the study of work and exercise physiology and shared their findings with Nilsen’s own. They eventually set the results out in their Textbook of Work Physiology, published in 1977.

‘I was lucky,’ Thor said, ‘I had a good backdoor education and a direct door to all this research. I had no degree in it. They had a lot of top younger people working with them.’

Another influence was the Swedish American Gösta ‘Gus’ Eriksen who came from Syracuse University in New York State to be Sweden’s national coach in the mid-1950s. He brought with him a dose of the style taught by Hiram Conibear at the University of Washington: ‘a smooth, flowing combination of the leg drive with a strong back and arms’.

Nilsen did not avoid the politics in Norwegian and Swedish rowing – far from it. He held various offices and positions of responsibility in both countries. Arguments raged over selection and composite crews. Sweden entered composites at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, and ‘Gus’ Eriksen followed precedent in the 1950s by forming a new, unofficial club named Three Towns, and manning it with talented recruits from three official clubs.

In the 1960s Norway’s training committee was often at odds with the federation’s leadership, the persistent problem being how to fit regions and fringe clubs into the selection procedure. When Thor became editor of Roing magazine in 1959 he published a strong case for selecting composite crews to represent the country. As the country’s foremost coach, he later proposed ‘a systematic structure for the training of instructors’. He was given the chance to implement his theory, and in collaboration with Professor Rodahl and the trainer Stein Johnsen unveiled what happens to a rower’s body during the rowing action. Assistance also came from Einar Gjessing’s invention of a rowing machine that measured strength and stamina. Norway’s first altitude camp took place at Dombås, north of Oslo, in 1967, and elite rowers experienced high altitude at Norefjellsstua near Oslo. Thus the importance of training coaches and looking after elite rowers came about. By 1980 Norway’s internal conflict was unified.

East Germans dominated the medal podium in the 1970s by pumping unlimited resources into research and performance. But they were not the only lateral thinkers rocking the boats. In addition to Thor’s enterprise in Norway, Dr Karl Adam upset old habits in West Germany and established a research academy in Ratzeburg. British rowing was presented with a revolutionary way of doing things when Rowing, a Scientific Approach was published in 1967. Coaches in the Soviet Union and its satellites who generally benefitted from sports science more advanced than their contemporaries on the west side of the Iron Curtain began to defect. Kris Korzeniowski moved from Poland to Canada and then to the US, Bob Janoušek came to Britain from Czechoslovakia, the Ukrainian Igor Grinko went to train scullers in Augusta in the US, and Romanian Reinhold Batschi settled in Canberra, Australia, via West Germany.

So when Spanish visionaries opened a national training centre at Banyoles and hired Nilsen to run it, lateral thinking about moving boats had spread its tentacles into many curious minds and up several creeks. Banyoles under Thor became a round-the-year centre of excellence attracting the biggest names in sculling, including the Finn Pertti Karppinen, China’s Zhang Xiuyun, Canada’s Trisha Smith, Britain’s Hugh Matheson and Riccardo Ibarra of Argentina.

Thor’s role in Catalonia came to an end in 1980 when Pedro Abreu, a Cuban who financed Banyoles’s boats, school and study centre, was kidnapped and held to ransom by Basque terrorists. But in 1981 the wily Norwegian moved to Italy’s new national rowing centre in a village by a lake in Umbria. Piediluco has good rowing water, a laboratory, a gym and conference rooms adjacent to the clubhouse, good food and hotel accommodation in a former nearby monastery, and the benefits of the latest advances in physiology. Nilsen came to Piediluco armed with a quarter-century of dialogue with open-minded experts and scientists, and athletes warmed to his regime and the cultural visits arranged by Thor’s wife Ingmarie. Thor was the glue that made it all work, always looking for the best for everyone.

As in Banyoles, the host federation allowed him to use the centre for FISA’s development campaign, a continuous education programme that eventually engaged 40 national teams to take part in camps and regattas at Piediluco. The world’s top coaches and athletes came there to eat, sleep and row together in the rarefied atmosphere created by Thor and Ingmarie. ‘Korzo’ Korzeniowski, the Polish-American who undertook coaching stints there, summarised the experience thus: ‘Discussions, dinners, testing, analysis and personal contact with top scientists created a special climate to suck in knowledge, and we finished up even more curious than when we started.’

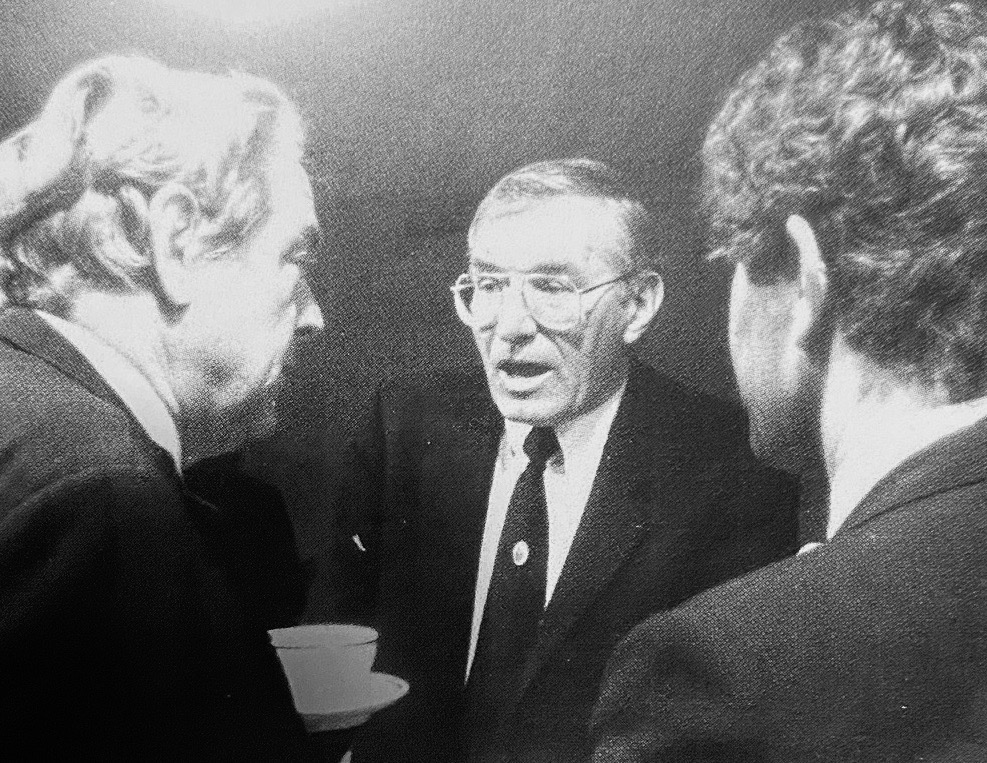

Thor’s own stint in Italy was marked by significant changes in the sport. World Rowing, then named Fédération Internationale des Sociétés d’Aviron (FISA), was fortunate to have a dynamic president in Thomi Keller, a Swiss rower elected in 1958 who had the vision to transform the federation from a European men’s competition club to a diverse worldwide organisation. He and Thor had much in common. They both ‘filled a room’ when they walked through its door. Both could punch above their weight, both were used to getting their own way. Both possessed wisdom and knew when to be diplomatic, and neither suffered fools gladly.

Thomi and Thor could have behaved like rival alpha males scrapping over the spoils of power while sharing passion for their poverty-stricken sport. But rowing was fortunate that its two giants together pounded the paths of regatta venues with their dogs, worked to create fair conditions on the water together and fought the athletes’ corner when the Olympics were embracing sponsorship, television and commercial pressures.

Keller had a big agenda. As a founding Olympic sport rowing depended on remaining in the Games. To avoid falling out of favour in the face of newer, more popular sports he realised that rowing must recruit member federations, persuade more of them to send crews to regattas, and attract the less bulky people of Asia and South America by promoting events for lightweights. Thomi also set about increasing numbers of junior and under-23 competitors and women, events for whom were introduced to the Olympics in 1976. He led rowing to pioneer round-the-year drug tests for elite athletes. He oversaw the revamping of the federation’s council by appointing East Europeans to responsible positions. He issued a ‘cook book’ on how to organise regattas. And in 1969 to 1987 he was president of the General Assembly of International Sports Federations (GAISF), to the irritation of the International Olympic Committee.

Among Thor’s achievements was the establishment of World Rowing’s fairness commission that operated in inclement conditions by driving hither and thither along a rowing course and stopping every now and then to operate the ‘grassometer’. This involved releasing a handful of grass to the wind to assess its strength and direction. Remedies for unfair racing conditions include changing the formula in use for seeding lanes (i.e. allotting the best lanes to the fastest semi-finalists), substituting time trials for heats, or re-allocating the six racing lanes by bringing spare lanes seven and/or eight into play).

Thor’s most significant contribution came in 1986 when he wrestled $85,000 per year for four years from Olympic Solidarity to fund the development programme, a year that was a giant leap forward for rowing’s multi-faceted ‘underdeveloped’ world. The plans included coach education, courses in boat building and maintenance, a new world cup regatta series, establishing a secretariat, promoting rowing for lightweights, and finding new sources of income. Other schemes involved donating used boats to new clubs and converting shipping containers into complete starter clubs equipped with boats, oars and tools, while the container itself served as boat shed. Twenty-five top coaches were summoned to Ratzeburg academy and given three days to compile a universal teaching manual. Thor’s assistant Matt Smith began his appointment by taking a whirlwind fact-finding tour of 29 countries, 18 of which were in Asia and six in Europe under Soviet influence.

Before the 1990s were out, the development leader fell out with the Italians when their incoming president, Gian Antonio Romanini, abolished the Norwegian’s licence to hire coaches and select teams. Thor and Ingmarie headed for home in Strömstad, Sweden, a ferry port and resort with lakes and seawater to accommodate rowing crews. The perpetual worldwide seminar entered its next phase with a straightforward message: ‘Growing rowing is the only way to ensure a future for the sport in the Olympic arena.’ Soon foreign tongues were heard around Ingmarie’s hostel for backpackers, and Thor coached crews training in Strömstad, and many more on his phone. The Irish rower Neville Maxwell described it thus: ‘Thor gave us structure, leadership and direction, and if criticised, he stood firm. His lesson was how to get the best out of oneself. He made us challenge our mentality.’

Thor officially retired in 2017, aged 85, but his mobile never stopped. Sheila Stephens, his successor, recalls learning the job on the hoof when she joined FISA in 2002. ‘I spoke to Thor more than anyone else, several times a day, happy that he gave me guidance and allowed me to try and find my way. He mentored me, and it was one of the best experiences of my life.’

In 2020 the international federation had around 150 members and more than 100 nations involved in schemes orchestrated by Stephens in Lausanne. Development coaches were at work in five continents and there were hook-ups between mentoring and developing countries, examples being Britain and countries of the Commonwealth and France and French speaking countries in Africa.

Chris Perry, the coach for Asia based in Hong Kong, summarises the task thus: ‘We are trying to sell rowing, so we have to integrate rowing into society, not just make it about racing at the Olympics. Thor made his reputation by thinking outside the box, always throwing out ideas. Our clients need education and all of those other things before they appear at the Olympics.’

Roger Wiggin is a coach who benefitted from Thor’s teaching: ‘What he said was very simple. Here was someone with a profound understanding of biomechanics, moving boats through water, interaction between rower, water and boat, training physiology, more than anyone I had met by a long way.’

Nilsen coached only crews, never countries. His coaching results stack up to eight Olympic gold medals, more than 30 World Championship and a dozen national titles, a record that earned him World Rowing’s distinguished service to international rowing award.

Oswaldo Borchi, development coach for South and Central America, catches the Nilsen effect perfectly. ‘Rowing has two periods, BT and AT,’ he said. ‘Before Thor, there was nothing. After Thor there was application of science to style and training, shared information and open communication between coaches and crews. Thor is the Big Teacher.’

For Ingmarie who married him in 1969, Thor could have been the richest man in the world. ‘But he cannot live without passion. His father was like that and his daughter Aina, she’s the same. They work on interest and passion. Money is secondary. I think it’s nice. In him there is no jealousy.’

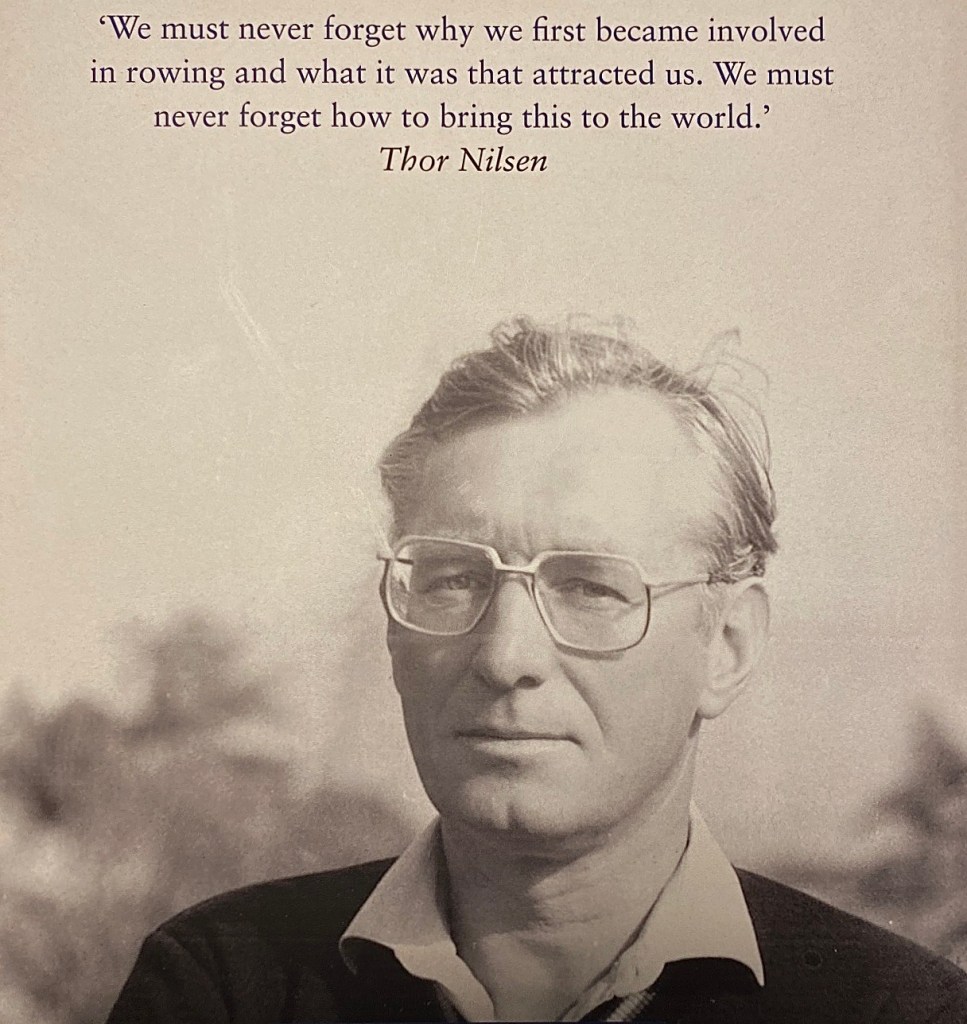

Thor coupled his passion with the Norwegian saying ‘ensam är stark’ that translates as ‘he who stands alone stands strong’. I surmise that the communicator who created a universe and secured rowing’s place in the Olympic Games will carry a cell phone when he enters the gates of the Great Enclosure in the Sky. Thor Nilsen, a maverick who was used to having his own way, deserves the last word, as he wrote in Regatta magazine in February/March 2003:

‘We must never forget why we first became involved in rowing and what it was that attracted us. We must never forget how to bring this to the world,’

Thor Sverre Nilsen, born 5 October 1931, Bærum (Norway), died 5 October 2023, Strömstad (Sweden). He is succeeded by his second wife Ingmarie, daughter Aina and son Stephen.