4 October 2023

By Tim Koch

Tim Koch concludes his study on amateurism as practiced through the years at Chester Regatta. (Part I, II, III, IV, V and VI)

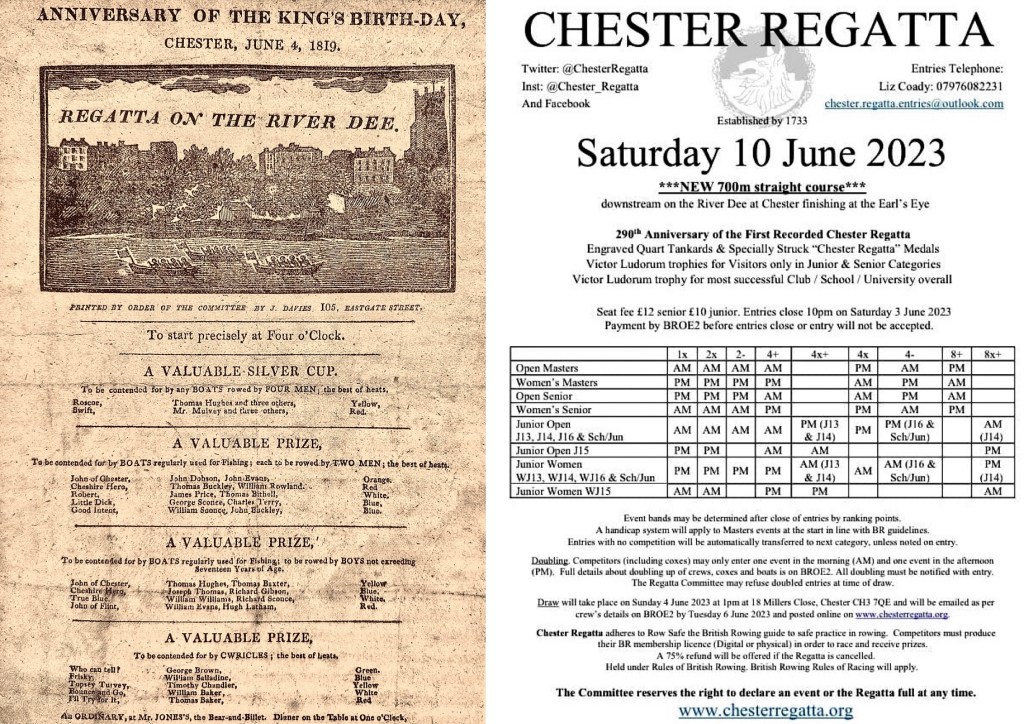

As Parts I to VI have hopefully shown, it took fifty-eight years, from the first regatta of 1814 to the 33rd regatta of 1872, for Chester to exclude all manual workers and become the sole preserve of so-called gentlemen amateurs.

Between the first of the Chester Regattas that was exclusively for gentlemen amateurs (strictly 1872 but arguably 1870 when a minor race for local soldiers was included) and before 1882 or 1883 when the event was run under the inflexible rules of the new guardians of strict amateurism and the manual labour bar, the Amateur Rowing Association (ARA), there was one small deviation. In 1881 only, a race for Coxed Fours (provided by the Committee) was open to Chester based soldiers, fishermen, artisans or watermen. Possibly, this was the last hurrah before coming under ARA rules.

Their affiliation to the ARA took much decision making regarding such things as amateur status out of Chester Regatta’s hands – whether they liked it or not.

In 1888, the Paulatim Club, composed of civilians and also privates and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) from the local garrison wanted to enter a crew of NCOs in that year’s regatta. They had previously raced at an ARA regatta at Bridgnorth, 60-miles south of Chester. Chester Regatta officials felt obliged to check with the ARA as to whether privates and NCOs were classed as amateurs. The ARA ruled that any soldier not an officer was a professional, much against the wishes of the regatta officials who had put one of the Paulatims on their committee. The Chronicle noted that, “the decision has created a strong feeling of disgust and indignation in the city.” A member of the Paulatims signing himself “Cantab” wrote to the Cheshire Observer of 7 July 1888:

There is such a term as “Gentlemen” Amateurs, but I think it is only a local one, and I consider any club or man who conducts himself in a proper and honourable manner may fairly claim even to that title.

Years later, nothing had changed. In 1911, the Cheshire Observer of 21 July reported on a meeting of the Chester City Council which discussed schemes to enable “the working classes” to hire boats at low rates:

(The Mayor) had the courage to say publicly what many people have been thinking for years, when he denounced the absurd rule of the Amateur Rowing Association on the question of amateurs. At this time… surely no one will defend it. The abolition of the distinction between a “gentleman” and an artisan is long overdue…

By 1934, twenty-three years and several mayors later, there was still no progress.

There is a wonderful twist to the mayor’s story outlined above and, if Charles Sconce was aware of it, he did not mention it in his interviews.

For generations, the Sconces were Chester fishermen and three of them are listed as competitors in the second regatta in 1815, the first time that names were recorded: George Sconce and George Dobson rowed Wincing Jenny in the fisherman’s two-oar race; G. Sconce and E. Randels rowed the Three Brothers and W. Sconce and J. Evans rowed the Happy in the Boys Under-17 Fishing Boat Race.

Newspaper reports show that from at least 1815, Sconce men, boys, wives and daughters all competed regularly in races for fishermen and/or fishing boats until the last such event that they were eligible for ended in 1868. In the 1829 regatta, the family particularly excelled themselves: the race for “Pleasure Boats of an Inferior Class” had one Sconce competing; the race for “Fishing Boats Rowed by Fishermen” had five; the race for “Wives of Fishermen” had three. Sconces were among the winners in all of these three events. The Chronicle noted in 1831 that (the Sconce wives) seem to have acquired the art of rowing with equal ability to their husbands. In 1843, the same newspaper recorded that, there were no less than four generations of the (Sconce) family on the river, all of whom came off winners!

Assuming that the family remained in manual trades, no Sconce could row at Chester Regatta between 1868 and 1937 when the Amateur Rowing Association finally dropped the manual labour bar and manual and non-manual workers could in theory row with and against each other. Even in Chester, sited a long way from the influence of London and the South, it had been a long time coming.