3 October 2023

By Tim Koch

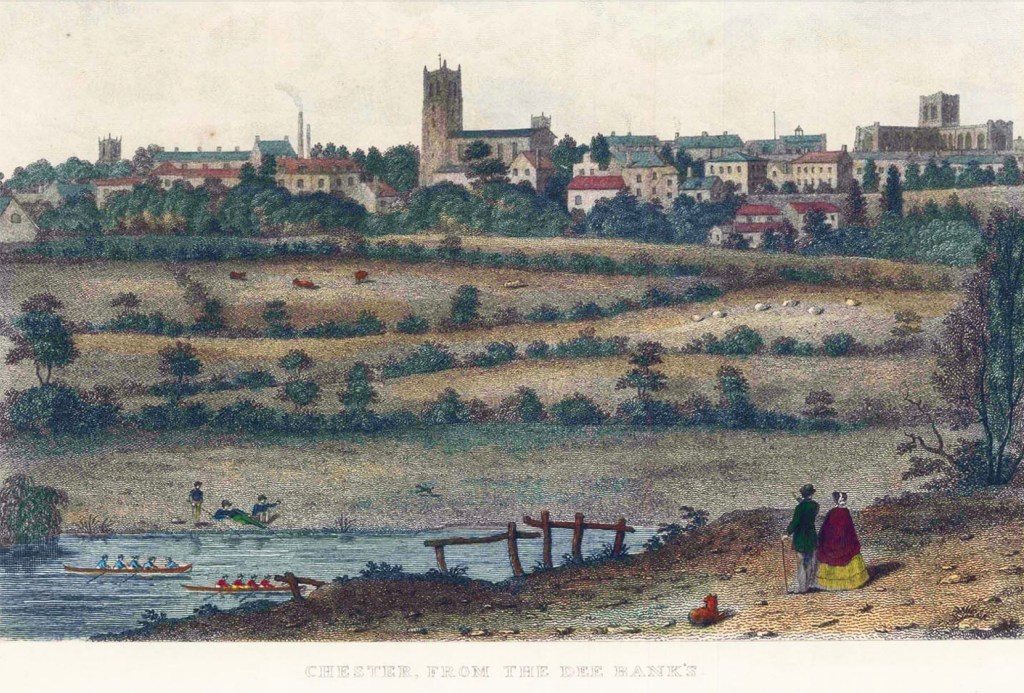

Tim Koch continues to try and make the complicated history of amateurism at Chester Regatta accessible and readable. (Part I, II, III, IV and V)

In Part V, I wrote:

The years 1839 to 1871 are significant in that it is the period when Chester Regatta was run by gentlemen amateur rowers but it still offered events for other social classes.

The table in… Part V (covered) the 13th to 25th Regattas, 1839 to 1855.

The second table in (this) Part VI covers the 26th to 33rd Regattas, 1862 to 1872.

The break between the two, 1856 to 1861, is simply one of convenience, there were no regattas in those years.

After each table, I will attempt to summarise the various changes that took place.

From 1862, the 4-oared inrigged event for gentlemen amateurs was stopped, there was only the outrigged event.

In 1863, the “Open” category for 4-oar outrigged boats was given the title of the “Waterman’s Prize”. Whether “watermen” strictly meant those who had served an apprenticeship or also included non-apprentice served professionals, I do not know. Also in 1863, the first age-related gentlemen’s event was offered (a 4-oar clinker inrigged race for gentlemen amateurs under 18s).

After a three-year hiatus, the 1867 regatta took place and continued to offer more events for gentlemen amateurs. The upper classes had three events in 1862, four in 1863, five in 1864 and seven in 1867.

The three regattas held in 1868 (the 30th), 1869 (31st) and 1870 (32nd) were very significant. By the end of that short period, all the events for non-gentlemen amateurs and for professionals were dropped and the result was that from 1872 (33rd) onwards, Chester Regatta was for gentlemen amateurs only.

In 1868 and after, no race for women was offered, 1867 was the last time what was effectively a contest for fishermen’s wives and daughters took place. The event had been put on in the first regatta in 1814 but was dropped for the next five held between 1815 and 1828. There was a return in 1829 but it was not offered again in 1830. However, the women’s race was held continuously in all twenty-one regattas between 1831 and 1867.

I can only speculate why the women’s race, popular with many spectators, was dropped. It was never about “women’s sport” or gender equality or any such anachronisms. Newspaper reports on the women’s race were occasionally complementary. In 1843, the Courant reported: The winning boat was rowed by two fine-looking women, who would have proven tough opponents to some of the men… However, press reports were generally scanty and patronising and gave the idea that the women’s race was a spectacle of fouling and foul language in which no umpire got involved.

Following the 1838 women’s race, the Courant wrote, it afforded a great deal of pleasure to spectators and at the (finish) the “ladies” had a vast deal of “polite” conversation regarding the fairness of the race… The Courant of 7 September 1853 said that, This race, as usual, excited much merriment, as the “ladies” are not particular in their salutations one with the other… One of the Nancy’s crew caused some excitement after the race by bringing her boat opposite the Committee ground and dancing on the stern.

The competitors were literally “fishwives” and may have often acted as the common shrewish stereotype, much to the amusement of onlookers. I imagine that the women’s race was eventually judged a too coarse and too undignified an event to be associated with a genteel and respectable regatta.

The 1869 regatta saw the first references to “Senior” and “Junior” events, but these were nothing to do with age, they referred to the number and the standard of wins that had been achieved by each competitor.

More importantly, in 1869, no more races were offered for mechanics and/or fishermen and for those who were effectively “tradesmen amateurs.” Also in 1869, the 4-oar race rowed by Chester boys (probably all fishermen’s sons) run since 1840 was no longer offered. The only concession to events for the lower social classes was the addition of a race for 2-oar inrigged coxed boats for privates and NCOs of the local military garrison.

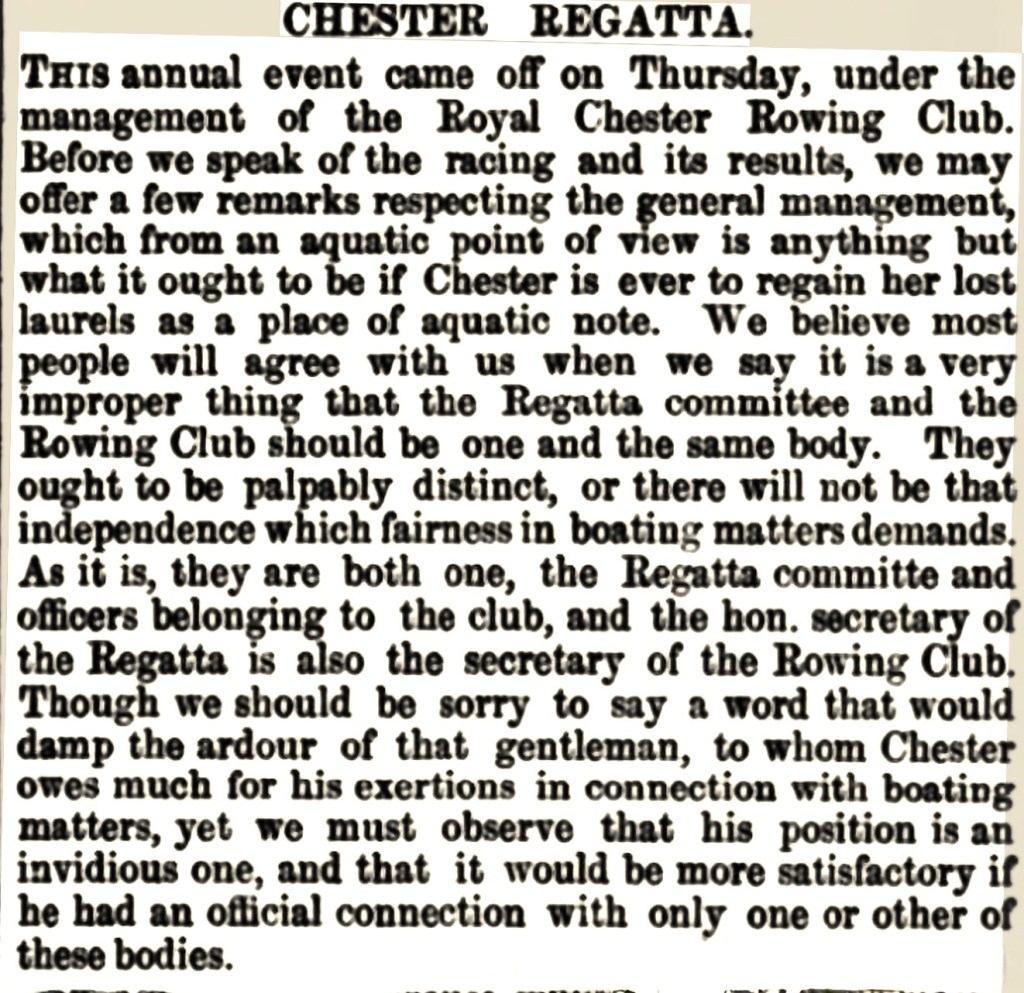

Immediately after the 1869 Regatta, the Chester Courant printed the opinion below.

Someone signing themselves “Rowlock” wrote in the Chester Courant of 13 July 1870: “The published programme of the coming Regatta has given great dissatisfaction on account of the omission of the Watermen’s and Mechanic’s Prizes…” He also complained about Royal Chester RC allegedly arranging events to suit its particular strengths and weaknesses: “When public money is given, something more than a club regatta is expected…”

The next week, the Chester Courant of 20 July 1870 published a reply from William Henry Churton, the Secretary of the RCRC. He dismissed the claims of aquatic gerrymandering in detail and then continued:

The mechanic’s races were discontinued… because they produced no sufficient amusement to the public, almost led invariably to a wrangle between the watermen and fishermen, and, after the race was over, to very considerable drunkenness on the part of the winners and their friends.

I very much regret that the watermen’s race had to be discontinued this year (but it) had become an absolute farce. For the last two or three years there had been no real competition for the £40 in money given by the Committee and, however glad we are to see our friends from Newcastle, the Committee very properly thought that an annual gift to them of £40 out of public money for coming down to show themselves was rather too much of a good thing.

At the public meeting where it was formerly proposed to hold the 1870 Regatta, the accusation that it was “all got up” by Royal Chester RC was discussed but the RCRC Secretary Churton, noted that it was actually very difficult to recruit people who were interested in organising the event and that only a few people put themselves forward, all of whom were members of RCRC. A resolution was passed declaring that the regatta committee should consist of members of Royal Chester “with others who may wish to join from the city and neighbourhood.” As someone who was once secretary to a regatta supposedly run by an open committee but one that unavoidably ended up being run by one club, I am entirely sympathetic to Churton.

In 1870, the Watermen’s Prize was dropped leaving the race for local soldiers as the only event not for gentlemen.

By the time of the next regatta, 1872, the military race was gone and just eight events were offered, all for gentlemen amateurs.

A few days before the 1872 “gentlemen only” regatta, the Cheshire Observer of 27 July 1872 wrote:

We hear that Chester Regatta, to take place on Tuesday next, will far outstrip all previous meetings of its kind, whether in point of numbers or quality of competitors…

The sport – there is no use in denying it – was at a low ebb in Chester. For whatever reason, it was not so popular, so that the present committee had a more than usually arduous task…

It is perhaps necessary to state that the regatta this year has been confined to gentlemen amateurs. The sight of professional watermen rowing may have been a treat, but even that was diluted somewhat when the facts were known.

Formerly the principal prize at the Chester Regatta was £40 and, on more than one occasion we believe, the race has been arranged beforehand, as much as £10 having been given to a crew to (lose) a race.

The conditions of the present regatta effectively guard against such practices by limiting the competition to amateurs and in the system of prizes.

In the final piece on Chester Regatta, Part VII, which will be published tomorrow, some final thoughts and images are put together.